13.3

Impact Factor

Theranostics 2017; 7(7):2048-2064. doi:10.7150/thno.19883 This issue Cite

Research Paper

PET Tracer 18F-Fluciclovine Can Detect Histologically Proven Bone Metastatic Lesions: A Preclinical Study in Rat Osteolytic and Osteoblastic Bone Metastasis Models

1. Research Center, Nihon Medi-Physics Co., Ltd., Chiba, Japan;

2. Division of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Received 2017-3-1; Accepted 2017-4-8; Published 2017-5-15

Abstract

18F-Fluciclovine (trans-1-amino-3-18F-fluorocyclobutanecarboxylic acid; anti-18F-FACBC) is a positron emission tomography (PET) tracer for diagnosing cancers (e.g., prostate and breast cancer). The most frequent metastatic organ of these cancers is bone. Fluciclovine-PET can visualize bony lesions in clinical practice; however, such lesions have not been described histologically.

Methods: We investigated the potential of 14C-fluciclovine in aiding the visualization of osteolytic and osteoblastic bone metastases (with histological analyses), compared with 3H-2-deoxy-2-fluoro-D-glucose (3H-FDG), 3H-choline chloride (3H-choline), and 99mTc-hydroxymethylene diphosphonate (99mTc-HMDP) by using triple-tracer autoradiography in rat breast cancer osteolytic (on day 12 ± 1 postinjection of MRMT-1) and prostate cancer osteoblastic (on day 20 ± 3 postinjection of AT6.1) metastatic models.

Results: The distribution patterns of 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-FDG, and 3H-choline, but not 99mTc-HMDP, were similar in both models, and the lesions where these tracers accumulated were, histologically, typical osteolytic and osteoblastic lesions. 99mTc-HMDP accumulated mostly in osteoblastic lesions. 14C-fluciclovine could visualize the osteolytic lesions as early as day 6 postinjection of MRMT-1. However, differential distributions in 14C-fluciclovine and 3H-FDG existed, based on histological differences: low 14C-fluciclovine and high 3H-FDG accumulation in osteolytic lesions with inflammation. In the osteoblastic metastatic model, visualization of osteoblastic lesions with 14C-fluciclovine was not clear, yet clearer than with 3H-FDG. Although half of the osteoblastic lesions with 14C-fluciclovine accumulation showed negligible 3H-choline accumulation in comparison, they were histologically similar to lesions with marked 14C-fluciclovine and 3H-choline accumulation.

Conclusion: These results suggest that fluciclovine-PET can visualize true osteolytic and osteoblastic bone metastatic lesions.

Keywords: breast cancer, fluciclovine, osteolytic/osteoblastic metastasis, prostate cancer, triple-tracer autoradiography.

Introduction

Breast cancer (BCa) and prostate cancer (PCa) are the most common primary tumors for women and men, respectively, and for patients with bone metastasis [1]. The 5-year survival rates of BCa and PCa are approximately 99% if the cancers are localized [2]. Approximately 4%-5% of patients with BCa and PCa have distant metastasis, including metastasis to the bone; however, their 5-year survival rates decrease to 25% and 28%, respectively [2]. Thus, accurate early diagnosis of bone metastasis is important in planning therapeutic strategies for PCa and BCa.

Bone metastases of PCa and BCa are predominantly osteoblastic and mixed osteolytic/osteoblastic metastasis, respectively, although most patients have both of these lesions [3]. A bone scan using 99mTc-hydroxymethylene diphosphonate (99mTc-HMDP)/99mTc-methylene diphosphonate (99mTc-MDP) is most commonly used to diagnose bone metastases. A bone scan is sufficiently sensitive to detect advanced skeletal metastatic lesions, but not early-stage bone metastases [4]. In addition, the specificity of a bone scan is limited because many other pathological conditions involve osteoblastic reactions—the identification of which is the basis of this technique [4]. Compared to bone scan, positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) with 2-deoxy-2-18F-fluoro-D-glucose (18F-FDG) has the advantage of detecting metastatic sites, including osteolytic lesions; however, it is not helpful in the diagnosis of osteoblastic lesions because these lesions have fewer malignant cells than osteolytic lesions [5]. Another PET tracer, 11C/18F-choline chloride (11C/18F-choline) shows high sensitivity and specificity for detecting bone metastasis of PCa [6]; however, the relatively high uptake of 11C/18F-choline or 18F-FDG by macrophages may cause false-positive imaging results [7]. There are many reviews on the potential of 18F-FDG-PET, 11C/18F-choline, and bone scan for the detection of bone metastases in patients with PCa and/or BCa [8-13].

18F-Fluciclovine, also called trans-1-amino-3-18F-fluorocyclobutanecarboxylic acid (anti-18F-FACBC; code name, NMK36, Nihon Medi-Physics; brand name, Axumin, Blue Earth Diagnostics), is an amino acid PET tracer that is transported by alanine-serine-cysteine transporter 2 (ASCT2) and L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1) [14-16]. The main characteristic of our PET tracer is its low uptake by inflammatory cells (e.g., macrophages) compared to 18F-FDG [15]. 18F-Fluciclovine-PET has been used for diagnosing cancers such as PCa [17-19], BCa [20,21], and glioma [22,23], in primary cancer and in nodal and bone involvement. In combination with external-beam radiotherapy, image-guided radiotherapy based on 18F-fluciclovine-PET has become possible in post-prostatectomy patients with recurrent PCa [24-26]. In cancer patients with bone metastasis, radiotherapy plays an important role not only with regard to its tumoricidal effect, but also in bone pain relief [27]. Therefore, if image-guided radiotherapy with 18F-fluciclovine-PET is to be applied for bone therapy, accurate diagnostic information such as the number and the location of bone metastatic lesions is required. Although 18F-fluciclovine-PET can reveal the number and the location of bony lesions [19], a few reports have demonstrated histological proof of 18F-fluciclovine accumulation in bone metastatic lesions. Moreover, these studies were limited to osteolytic metastasis [17,18]. Thus, we believe it is worthwhile to explore the ability of 18F-fluciclovine to detect osteolytic and osteoblastic bone metastatic lesions, with histological validation.

In this study, we investigated the potential of 18F-fluciclovine to aid the visualization of osteolytic and osteoblastic bone metastases with pathological analyses, compared to visualization using 18F-FDG, 11C/18F-choline, and 99mTc-HMDP by using triple-tracer autoradiography in rat BCa osteolytic and PCa osteoblastic metastatic models.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

All reagents were purchased from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA), Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan), and Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Osaka, Japan), unless otherwise stated. 14C-labeled fluciclovine and 3H-labeled FDG or choline were used instead of 11C/18F-labeled tracers because their long half-lives make them more suitable for experiments than tracers labeled with 11C (20 minutes) or 18F (110 minutes). 14C-Fluciclovine (trans-1-amino-3-fluoro[1-14C]cyclobutanecarboxylic acid; specific activity [SA], 2.08 GBq/mmol; radiochemical purity (RCP), >98%) was commercially synthesized by Nemoto Science (Tokyo, Japan), as described previously [14]. [5,6-3H]-2-Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (3H-FDG; catalog number: ART0105; SA, 2.22 TBq/mmol; RCP, >99%) was purchased from American Radiolabeled Chemicals (St. Louis, MO, USA). [methyl-3H]-Choline chloride (3H-choline; catalog number: NET109; SA, 2.897 TBq/mmol; RCP, >97%) was obtained from PerkinElmer (Waltham, MA, USA). Our company, Nihon Medi-Physics (Tokyo, Japan), produced 99mTc-HMDP (740 MBq/vial; RCP, >95%).

Cell culture

A rat BCa cell line, MRMT-1, and a rat PCa cell line, AT6.1, were procured from RIKEN BioResource Center (Tsukuba, Japan; obtained in January 2014) and European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (Salisbury, UK; obtained in October 2014), respectively, and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD, USA), 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 100 U/mL penicillin.

Animal models

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (9-12 weeks old; CLEA Japan, Tokyo, Japan) were used for all experiments. All animals were anesthetized with 1% isoflurane (catalog number: 871119; Pfizer Japan, Tokyo, Japan). In the surgical operations, 0.5% meloxicam (catalog number: DY120028; Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica, Tokyo, Japan) was injected subcutaneously in the rats to relieve pain. Osteolytic and osteoblastic lesions were induced in the tibia and/or femur of the experimental rats. A summary of the experimental setup is provided in Table 1.

Summary of the experimental setup.

| Animal models | Tracers | Evaluated lesions | Figure |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCa OL model | 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-FDG, 99mTc-HMDP | OL, pTBF, Tumor | 3 |

| OL (fibrous stroma in tumor tissue) | 4 | ||

| OL, pTBF (pTBF adjacent to OL) | 5 | ||

| OL (early stage of bone metastasis) | 6 | ||

| PCa OB model | 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-FDG, 99mTc-HMDP | OB, pTBF, Tumor | 7 |

| 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-Choline, 99mTc-HMDP | 8 | ||

| DH model | 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-FDG, 99mTc-HMDP | BBF | 9 |

| 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-Choline, 99mTc-HMDP | 10 |

BBF: bland bone formation, BCa: breast cancer, DH: drill-hole, OB: osteoblastic, OL: osteolytic, PCa: prostate cancer, pTBF: peri-tumor bone formation

BCa osteolytic bone metastatic model

A cell suspension of MRMT-1 was injected into the saphenous artery of the right and/or left hind leg of rats, as described in a previous report [28], with a minor modification. The femoral, descending genicular, popliteal, and saphenous arteries and veins were freed from the surrounding fat tissue and nerves. To mobilize the blood flow to the descending genicular and popliteal arteries, both of which supply the knee joint and muscles of the hind legs, the femoral and saphenous arteries were temporarily occluded by ligating them with a surgical thread at a position between the descending genicular and the superficial epigastric artery's origin, and distal of the saphenous artery, respectively. One drop of 4% papaverin solution (catalog number: 871243; Nichi-Iko Pharmaceutical, Toyama, Japan) was applied onto the saphenous artery between the surgical threads. One hundred microliters of a cell suspension containing 2.5 × 104 MRMT-1 cells in Hank's Balanced Salt Solution without Ca2+ and Mg2+ [HBSS(-)] was injected into the saphenous artery using a syringe with a 29G needle. After perforating the artery, the saphenous arterial wall was sealed with a piece of fat tissue, the surgical threads were removed, and the operation site was closed. Development of osteolytic lesions was monitored by a microfocus X-ray imaging system (μFX-1000; FUJIFILM Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) or a preclinical imaging system (FX3000 CT, TriFoil Imaging, Chatsworth, CA, USA) and triple-tracer autoradiography was performed 6 days or 12 ± 1 days after the cell injection.

PCa osteoblastic bone metastatic model

An ALZET osmotic pump (catalog number: 2ML4; Durect Corporation, Cupertino, CA, USA) was filled with 50 mg/mL of cyclosporin A (catalog number: 873999; Novartis Pharma, Basel, Switzerland), which were subcutaneously implanted in the rats to suppress the immune system 3-5 days before the cell injection. One hundred microliters of a suspension containing 2 × 105 AT6.1 cells in HBSS(-) was then intra-arterially injected into rats by using the procedure mentioned in “BCa osteolytic bone metastatic model”. The development of osteoblastic lesions was monitored visually by FX3000 CT, and triple-tracer autoradiography was conducted 20 ± 3 days after the cell injection.

Drill-hole (DH) model

Two holes, each with a diameter of 1 mm, were drilled in the cortical bone of the tibia of the rats to induce the formation of new bone. Each hole was sealed by using a piece of fat tissue. New bone formation was confirmed visually by FX3000 CT, and triple-tracer autoradiography was evaluated 8 ± 1 days postdrilling.

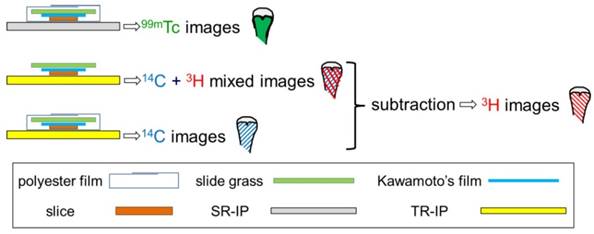

Triple-tracer autoradiography

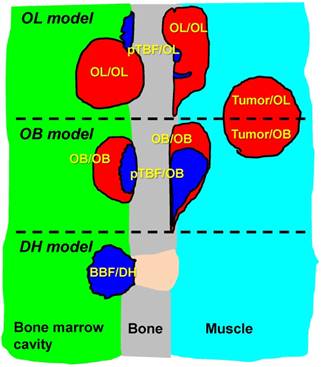

To compare the distribution of each tracer visually in identical lesions, we performed triple-tracer autoradiography using 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-FDG, and 99mTc-HMDP in the BCa osteolytic model (five hind legs), the PCa osteoblastic model (six hind legs), and the drill-hole (DH) model (three hind legs), or 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-choline, and 99mTc-HMDP in the PCa osteoblastic model (six hind legs) and the DH model (three hind legs). Triple-tracer autoradiography was conducted in the osteoblastic model only because bone metastasis in PCa patients is predominantly osteoblastic, as described above and the major PET tracer for PCa is currently 11C/18F-choline as mentioned in the Discussion. Rats were fasted overnight. The tracers 14C-fluciclovine (2.75 MBq/kg), 3H-FDG or 3H-choline (18.5 MBq/kg each), and 99mTc-HMDP (74 MBq/kg) were injected into the tail vein of an identical rat. 14C-Fluciclovine and 3H-FDG or 3H-choline were allowed to remain in circulation for 30 minutes, and 99mTc-HMDP was allowed to remain for 2 hours before euthanizing the animal. The animals were sacrificed under anesthesia by drawing blood from the abdominal aorta. The tibiae and femora were removed and frozen in isopentane/dry ice for 10 seconds. They were embedded in super-cry embedded medium (SCEM) (catalog number: 8091140; Section-Lab, Hiroshima, Japan) and frozen again in isopentane/dry ice until the SCEM had set. The frozen samples were placed in the chamber of a CM3050S cryostat (Leica Microsystems, Tokyo, Japan) at -20°C for at least 30 minutes and sectioned with the cryostat at -20°C with an adhesive film (Cryofilm Type 2C(9), catalog number: 8091100; Section-Lab) using Kawamoto's film method [29]. Fifteen serial sections (12 sections of 5-μm slices and 3 sections of 10-μm slices for the histological and autoradiography specimens, respectively) were obtained. Each section was mounted on a glass slide. To obtain images generated by the 99mTc-isotope, super resolution screen (SR) imaging plates (IPs) (FUJIFILM Corporation) were exposed for 1 hour to dried 10-μm slices wrapped in a 12-μm thick polyester film (Lumirror; catalog number: S10#12; TORAY Industries, Tokyo, Japan), which absorbs low-energy 3H isotopes (Fig. 1). Under these conditions, 14C caused no blackening of the SR-IP, even after a 1-hour exposure. This factor thus excluded cross-contamination by 14C in the 99mTc autoradiographs. The next two frozen sections adjacent to the 99mTc-autoradiographed section were stored at -20°C for 5 days to allow complete 99mTc decay. Following this procedure, tritium screen (TR)-IPs (FUJIFILM Corporation) were exposed to dried sections with and without the 12-μm thick polyester film for 7 days to obtain 14C images and 3H + 14C mixed images, respectively (Fig. 1) [30]. The IPs were developed with a FLA-7000 imaging analyzer (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). The 3H images were finally generated by subtracting the 14C images from the 14C + 3H images by using ImageJ software (ver. 1.48; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) (Fig. 1). All images were processed by ImageJ software. Images of 14C, 3H, and 99mTc obtained from a serial section were stacked in a single window by using the “Stack” function of the ImageJ software. For image registration of the three images, each image was positioned precisely by using several internal soft/hard tissue landmarks with characteristic anatomical information (except for lesions) such as growth plate, a portion of cortical bone of tibiae/femora (ex, distal end), patellae, cartilaginous tissue, and the region-of-interest (ROI) analysis was conducted. The ROIs were manually drawn around each lesion (target) while referring to the histological images of hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) and toluidine blue (TB) staining. Furthermore, three square, circular, or polygonal ROIs of random sizes were manually positioned on the normal regions of muscle surrounding tibiae and/or femora (ex. quadriceps femoris muscle, gastrocnemius muscle) and the average ROI count from the three ROIs was calculated as the background radioactivity. Then, the targetmean-to-backgroundmean (T/BG) ratios were calculated and lesion-based analyses were conducted. For the semi-quantitative criterion, a T/BG ratio ≥1.5 was significant (i.e., positive finding). In each model, the lesions corresponding to 99mTc-HMDP accumulation were defined as new bone formation according to the following grading system (see the schema in Fig. 2):

1. OL/OL: tumor lesions with bone absorption in osteolytic model (typical osteolytic lesions);

2. pTBF/OL: peri-tumor bone formation (pTBF) region where 99mTc-HMDP accumulated in the OL/OL;

3. Tumor/OL: tumor lesions other than the OL/OL and the pTBF/OL (ex. intramuscle tumor);

4. OB/OB: tumor lesions with pTBF in osteoblastic model (typical osteoblastic lesions);

5. pTBF/OB: pTBF region where 99mTc-HMDP accumulated in the OB/OB;

6. Tumor/OB: tumor lesions other than the OB/OB and the pTBF/OB (ex. intramuscle tumor);

7. BBF/DH: bland (non-tumor) bone formation region in the DH model.

Schema of triple-tracer autoradiography.

Histological analysis

The following procedures for each histological stain were performed qualitatively on 5-μm serial sections using general methods: H&E and TB staining for histological changes at the lesion sites; alkaline phosphatase (ALP) for osteoblast and fibroblast activity; and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining for osteoclast-activity. Anti-ASCT2 (J-25) polyclonal antibody (pAb) (catalog number: sc-130963; 1:40; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) and anti-LAT1 (H-75) pAb (catalog number: sc-134994; 1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for the amino acid transporters were used in the immunohistochemical assessments with EnVision+ System HR-labeled polymer anti-rabbit (catalog number: K4003; Dako Japan, Tokyo, Japan) and Liquid DAB+ Substrate Chromogen System (catalog number: K3468; Dako Japan). Immune cell infiltration of the lesions was detected immunohistochemically using combinations of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-anti-rat CD45RA monoclonal antibody (mAb) (clone: OX-33; catalog number: 554883; 1:100; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) for B cells, phycoerythrin (PE)-anti-rat CD8α mAb (clone: OX-8; catalog number: 554857; 1:100; BD Biosciences) for T cells, FITC-anti-rat CD68 mAb for monocytes/macrophages and osteoclasts (clone: ED-1; catalog number: MCA341F; 1:100; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA), and PE-anti-rat granulocyte mAb for neutrophils (clone: RP-1; catalog number: 550002, 1:100; BD Biosciences) (Note: Because the osteoblastic bone metastatic rat model used in this study was immunosuppressed by cyclosporin A, which can inhibit the function of lymphocytes, mAbs against T and B cells were not used.) In the immunofluorescent staining, the nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). A BZ-3000 HS all-in-one fluorescence microscope (Keyence Corporation, Osaka, Japan) was used for pathological examinations.

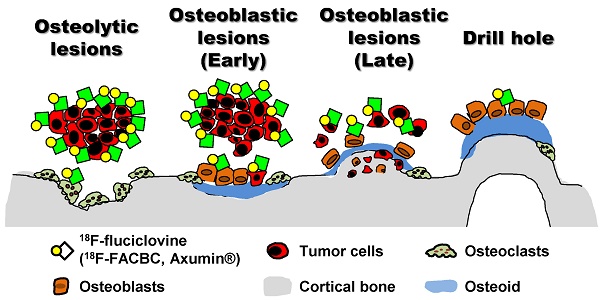

Schema of bony lesions in BCa osteolytic and PCa osteoblastic bone metastatic models and DH model. OL/OL lesions were defined as tumor mass with bone absorption observed in the osteolytic (OL) model. Some OL/OL lesions contained small new bone formation (pTBF) where 99mTc-HMDP accumulated intensely. OB/OB lesions in the osteoblastic (OB) model always contained pTBF in the tumor parenchyma. The pTBF contained osteoids and fewer cellular components (e.g., tumor cells, osteoclasts, and osteoblasts) compared with surrounding tumor tissues (see Fig. 7 and 8). These OL and OB lesions were formed on the cortical bone surface of the inner and/or outer bone marrow cavity of the tibiae and/or femora. Tumor mass located apart from the cortical bone (e.g., without bone absorption and pTBF) in the osteolytic and osteoblastic models were named tumor/OL and tumor/OB, respectively. BBF/DH regions were defined as bland (non-tumor) bone formation (BBF) in the DH model.

Statistics

The data are presented as the mean ± the standard deviation. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The two groups were compared statistically using Wilcoxon rank sum test for non-normal distribution datasets or the F-test, followed by two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test or Welch's t-test for datasets with normal distribution. In all analyses, P < 0.05 was significant.

Results

BCa osteolytic bone metastasis model

In the BCa osteolytic bone metastatic model, 52 tumor-relevant lesions (34 OL/OL, 16 pTBF/OL, and 2 Tumor/OL) were produced inside and/or outside the bone marrow cavity (i.e., at the cortical bone surface) of the tibiae and/or femora and intramuscularly 12 ± 1 days postinjection of the MRMT-1 cells.

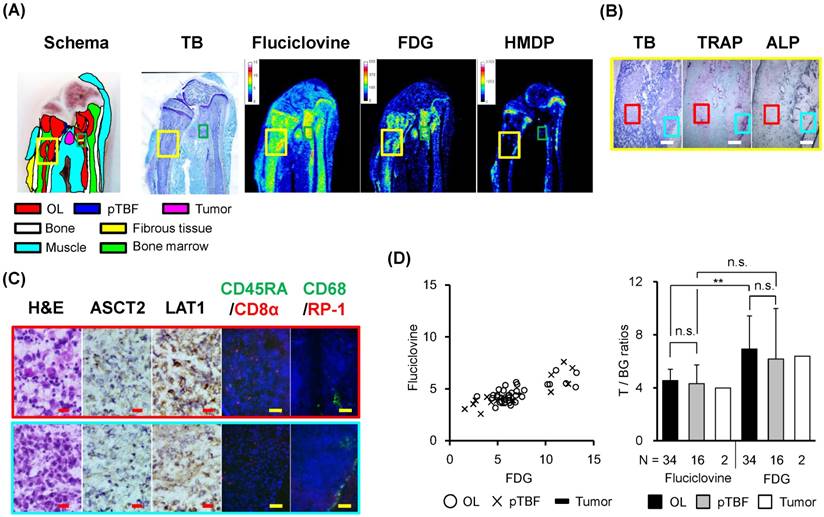

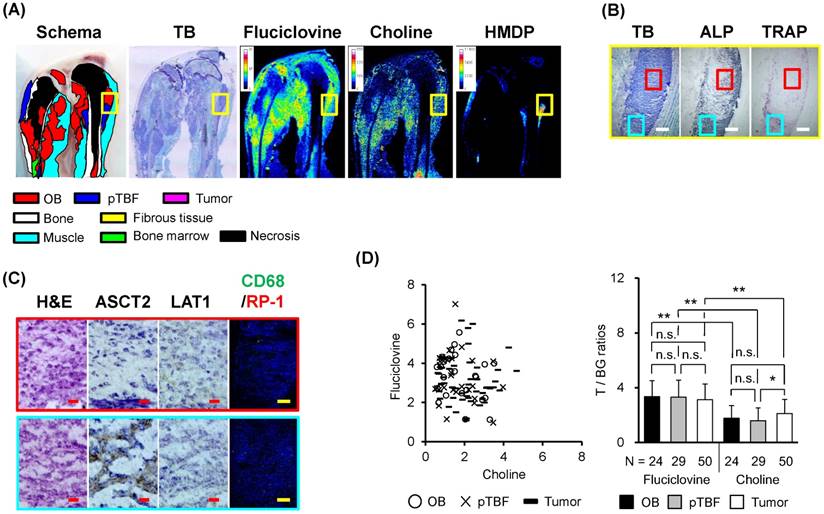

The distribution of 14C-fluciclovine, but not 99mTc-HMDP, was similar to that of 3H-FDG, although the physiological accumulation of 14C-fluciclovine was moderate in bone marrow (Fig. 3A).The areas where 14C-fluciclovine and 3H-FDG accumulated were tumors histologically, although 99mTc-HMDP did not accumulate in the tumor itself (Fig. 3A). For example, the right tumor in the yellow frames in Fig. 3A showed high accumulation of both tracers; this was a typical osteolytic lesion characterized by resorption pits adjacent to the tumor mass and by TRAP+- and CD68+-cells on the cortical bone surface of the resorption pit, which indicated osteoclast infiltration (Fig. 3B and 3C). Most tumor cells expressed LAT1, whereas there were some ASCT2+-cells in the tumor tissues (Fig. 3C). The CD8α+-, CD45RA+-, or RP-1+-inflammatory cells were few in the right tumor mass. Interesting, the osteolytic tumor tissues were surrounded by ALP+-cells, which indicated osteoblast and/or fibroblast infiltration (Fig. 3B). Compared with the right tumor, the left tumor tissue in the yellow frames had low 14C-fluciclovine accumulation, although 3H-FDG accumulation was high (Fig. 3A). The histological characteristics of this tumor were that TRAP and ALP activity occurred in the intra-tumor region rather than the peripheral area of this tumor tissue (Fig. 3B) and more inflammatory cells with bean-shaped nuclear cells, CD8α+ lymphocytes, and CD68+-cells in the tumor parenchyma (Fig. 3C).

Triple-tracer autoradiography (i.e., 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-FDG, 99mTc-HMDP) and histological analyses in BCa osteolytic bone metastatic model rats. (A) Macroscopic images (schema, TB) and representative autoradiograms of 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-FDG, and 99mTc-HMDP. The high-power microscopic fields correspond to the green frame on the TB image in Fig. 3A were shown in Fig. 4. Color scale bars on each autoradiogram represent Bq range for each tracer. (B) The low-power microscopic fields (TB, TRAP, ALP) correspond to the yellow frames on the images in Fig. 3A. The TB image shows two tumor masses in the bone marrow cavity. TRAP and ALP staining show osteolytic and osteoblastic activities, respectively. The white scale bars indicate 500 μm. (C) The high-power microscopic fields (H&E, ASCT2, LAT1, CD45RA/CD8α, CD68/RP-1) correspond to the red and cyan frames on the low-power fields in Fig. 3B. The lesion in the red frame contains more immune cell infiltrates, especially CD8α+ T cells and macrophages with bean-shaped nucleus (see H&E image) in addition to tumor cells, while the lesion in the cyan frame is composed mainly of tumor cells (H&E). Many CD68+ cells on the surface of cortical bone (e.g. osteoclasts) are observed (cyan frame). The red and yellow scale bars on each panel indicate 20 µm and 100 µm, respectively. (D) The T/BG ratios of 14C-fluciclovine and 3H-FDG on a per-lesion basis in OL/OL, pTBF/OL, and Tumor/OL lesions. The counter plots (left) and the mean ± standard deviation (right) are shown. The numbers under each column indicate the number of lesions. ** P < 0.01, n.s. not significant.

Comparison of the detection rates of 14C-fluciclovine versus 3H-FDG, and 14C-fluciclovine versus 3H-choline in osteolytic and osteoblastic lesions (lesion-based analysis).

| Fluciclovine vs. FDG in the OL/OL lesions | Fluciclovine vs. FDG in OB/OB lesions | Fluciclovine vs. choline in the OB/OB lesions | ||||||||||||||||

| Fluciclovine | Fluciclovine | Fluciclovine | ||||||||||||||||

| Posi | Nega | Total | Posi | Nega | Total | Posi | Nega | Total | ||||||||||

| FDG | Posi | 34 | 0 | 34 | FDG | Posi | 17 | 0 | 17 | Choline | Posi | 10 | 2 | 12 | ||||

| Nega | 0 | 0 | 0 | Nega | 0 | 0 | 0 | Nega | 12 | 0 | 12 | |||||||

| Total | 34 | 0 | 34 | Total | 17 | 0 | 17 | Total | 22 | 2 | 24 | |||||||

| %Posi of FDG: | 100 | %Posi of FDG: | 100 | %Posi of choline: | 50.0 | |||||||||||||

| %Posi of fluciclovine: | 100 | %Posi of fluciclovine: | 100 | %Posi of fluciclovine: | 91.7 | |||||||||||||

| Fluciclovine vs. FDG in the pTBF/OL lesions | Fluciclovine vs. FDG in the pTBF/OB lesions | Fluciclovine vs. choline in the pTBF/OB lesions | ||||||||||||||||

| Fluciclovine | Fluciclovine | Fluciclovine | ||||||||||||||||

| Posi | Nega | Total | Posi | Nega | Total | Posi | Nega | Total | ||||||||||

| FDG | Posi | 16 | 0 | 16 | FDG | Posi | 17 | 1 | 18 | Choline | Posi | 11 | 1 | 12 | ||||

| Nega | 0 | 0 | 0 | Nega | 4 | 1 | 5 | Nega | 16 | 1 | 17 | |||||||

| Total | 16 | 0 | 16 | Total | 21 | 2 | 23 | Total | 27 | 2 | 29 | |||||||

| %Posi of FDG: | 100 | %Posi of FDG: | 78.3 | %Posi of choline: | 41.4 | |||||||||||||

| %Posi of fluciclovine: | 100 | %Posi of fluciclovine: | 91.3 | %Posi of fluciclovine: | 93.1 | |||||||||||||

| Fluciclovine vs. FDG in the Tumor/OL lesions | Fluciclovine vs. FDG in the Tumor/OB lesions | Fluciclovine vs. choline in the Tumor/OB lesions | ||||||||||||||||

| Fluciclovine | Fluciclovine | Fluciclovine | ||||||||||||||||

| Posi | Nega | Total | Posi | Nega | Total | Posi | Nega | Total | ||||||||||

| FDG | Posi | 2 | 0 | 2 | FDG | Posi | 49 | 2 | 51 | Choline | Posi | 30 | 3 | 33 | ||||

| Nega | 0 | 0 | 0 | Nega | 0 | 1 | 1 | Nega | 17 | 0 | 17 | |||||||

| Total | 2 | 0 | 2 | Total | 49 | 3 | 52 | Total | 47 | 3 | 50 | |||||||

| %Posi of FDG: | 100 | %Posi of FDG: | 98.1 | %Posi of choline: | 66.0 | |||||||||||||

| %Posi of fluciclovine: | 100 | %Posi of fluciclovine: | 94.2 | %Posi of fluciclovine: | 94.0 | |||||||||||||

Positive (Posi): T/BG ratio ≥ 1.5, Negative (Nega): T/BG ratio < 1.5. Because the accumulation of tracers in each lesion was confirmed histologically, the positive and negative results indicate true-positive and false-negative, respectively, in this study.

On the lesion-based analysis of the osteolytic bone metastatic model, the distribution of T/BG ratios of 14C-fluciclovine in OL/OL, pTBF/OL, and Tumor/OL lesions were narrow, while those of 3H-FDG were broad as shown in the counter plot (Fig. 3D). A statistical significant difference was detected only between OL/OL lesions of both tracers (Fig. 3D). The detection rates of the lesions with a T/BG ≥1.5 were 100% for OL/OL, pTBF/OL, and Tumor/OL lesions for both tracers (Table 2). (Note: positive and negative findings for the tracers indicated true-positive and false-negative, respectively, because each lesion was confirmed histologically.)

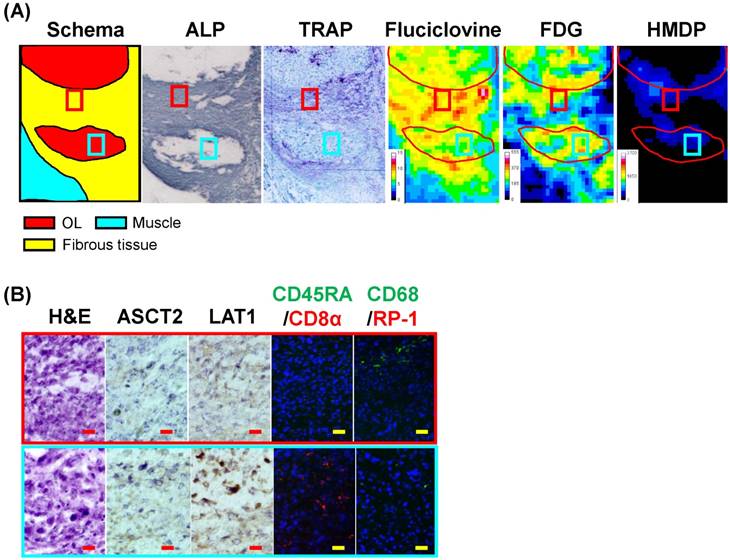

By using the osteolytic bone metastatic model, we observed some characteristic accumulation of tracers at lesions that closely mimics clinical findings. One of the lesions was observed in an OL/OL lesion invading the outer region of the bone marrow cavity (the green frame in the Fig. 3A): fibrous stroma in tumor tissue. It showed that equal or greater accumulation of 14C-fluciclovine, but not 3H-FDG and 99mTc-HMDP, in fibrous stromal tissues surrounding the tumors (the yellow region on the schema in Fig. 4), compared to that of the tumor parenchyma containing necrotic cells (the red region on the schema in Fig. 4). ALP and TRAP activities existed in the fibrous area (Fig. 4). Some cells in both areas were positive for ASCT2 and LAT1, and there were CD8α+ T-lymphocytes in the tumor parenchyma, but not in the stroma (Fig. 4). CD68+-positive cells, but not multinuclear cells, indicated the presence of monocytes/macrophages in the border of the fibrous tissue and tumor parenchyma (Fig. 4).

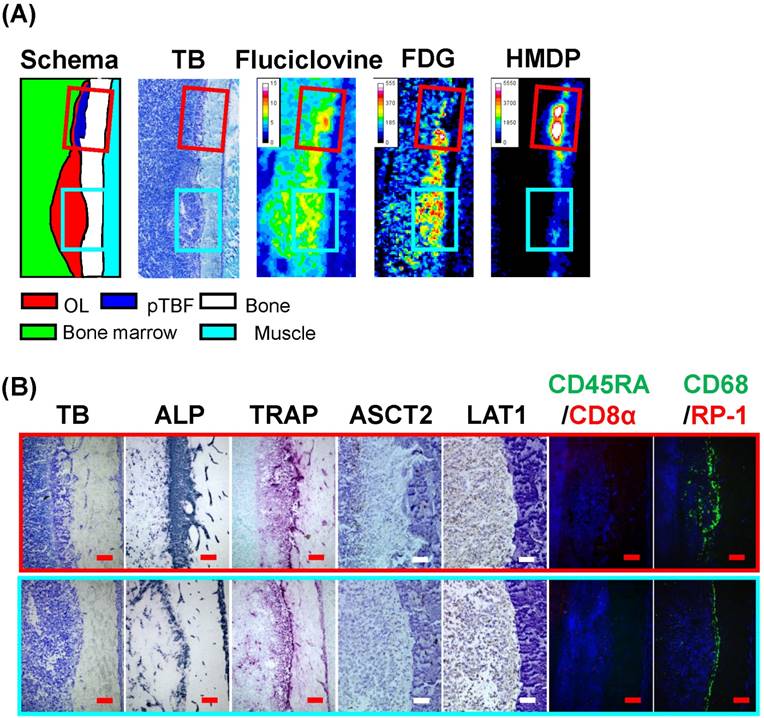

Another characteristic accumulation of tracers in the osteolytic bone metastatic model occurred in a pTBF/OL lesion, as shown in Fig. 5. It was characterized by a bone formation lesion adjacent to an OL/OL lesion with a resorption pit (cyan and red frames on the schema). The pTBF/OL lesion was small but had hyper new bone formation composed of osteoids and extensive ALP and TRAP activities. 14C-Fluciclovine accumulated in the OL/OL and the pTBF/OL lesions, whereas 3H-FDG and 99mTc-HMDP accumulated in only the OL/OL and the pTBF/OL lesions, respectively. In the OL/OL lesion, LAT1-, but not ASCT2-, positive cells were scattered broadly in the tumor area. In the pTBF/OL lesion, ASCT2+-cells were located in the outer border of the pTBF, and LAT1-expressing cells were inside and outside the pTBF. In the OL/OL and pTBF/OL lesions, there were few CD8α+- or CD45RA+-lymphocytes and granulocytes; however, there were many CD68+ cells (probably osteoclasts).

Early detection of osteolytic bone metastatic model lesions with 14C-fluciclovine

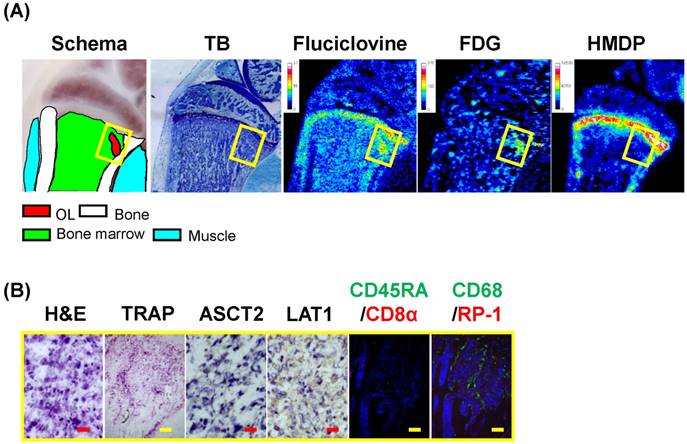

The previously described osteolytic bone metastatic models were used 12 ± 1 days postinjection of MRMT-1 cells; thus, the lesions showed drastic bone absorption with a large number of cancer cells. However, 14C-fluciclovine and 3H-FDG, but not 99mTc-HMDP, could reveal a lesion without extensive bone absorption in the tibia as early as 6 days post-injection of MRMT-1 (Fig. 6). The T/BG ratios of 14C-fluciclovine and 3H-FDG were 5.8 and 6.1, respectively. Histological examinations showed that the lesion between the trabeculae was invaded by tumor cells positive for ASCT2 and LAT1, and TRAP and CD68 staining revealed extensive osteoclast infiltration on the trabeculae, which suggested that bone absorption was in progress on the surface of the trabeculae and that the lesion was in an early phase of tumor metastasis. The lesion contained few inflammatory cells, except for CD68+ cells.

PCa osteoblastic bone metastasis model

In the PCa osteoblastic bone metastatic model, 92 tumor-relevant lesions (17 OB/OB, 23 pTBF/OB, and 52 Tumor/OB) and 103 tumor-relevant lesions (24 OB/OB, 29 pTBF/OB, and 50 Tumor/OB) formed in the hind legs of rats used for triple-tracer autoradiography with 14C-fluciclovine/3H-FDG/99mTc-HMDP and with 14C-fluciclovine/3H-choline/99mTc-HMDP, respectively, 20 ± 3 days postinjection of the AT6.1 cells. Most OB/OB lesions were on the cortical bone surface of the outer bone marrow cavity of the tibiae and/or femora.

Triple tracer autoradiography (i.e., 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-FDG, 99mTc-HMDP) and histological analyses in an osteolytic lesion in the outer of bone marrow cavity in a BCa osteolytic bone metastatic model rat. (A) The schema, magnified histological images (ALP, TRAP), and the autoradiograms of 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-FDG, and 99mTc-HMDP correspond to the green frame on the TB image in Fig. 3A. The fibrous area (yellow region), but not the tumor area (red region), shows ALP (probably fibroblasts) and TRAP (probably monocytes/macrophages) staining. Color scale bars on each autoradiogram represent Bq range for each tracer. (B) The high-power microscopic fields (H&E, ASCT2, LAT1, CD45RA/CD8α, CD68/RP-1) correspond to the red and cyan frames on the images in Fig. 4A are shown. CD68+ monocytes/macrophages and CD8α+ T cells are infiltrating into the fibrous area (red frame) and the tumor area (cyan frame). The red and yellow scale bars on each panel indicate 20 μm and 100 μm, respectively.

Triple tracer autoradiography (i.e., 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-FDG, 99mTc-HMDP) and histological analyses in an osteolytic metastatic lesion adjacent to an osteoblastic metastatic lesion in a BCa osteolytic bone metastatic model rat. (A) The schema, magnified histological images (TB), and the autoradiograms of 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-FDG, and 99mTc-HMDP are shown. The red and cyan frames correspond to the osteoblastic and osteolytic lesions, respectively. Color scale bars on each autoradiogram represent Bq range for each tracer. (B) The high-power microscopic fields (TB, ALP, TRAP, ASCT2, LAT1, CD45RA/CD8α, CD68/RP-1) correspond to the red and cyan frames on the images in Fig. 5A are shown. The pTBF in the osteoblastic lesion (red frame) shows intense osteoblastic (ALP) and osteolytic (TRAP) activities, while these activities are positive for the cells near/on the surface of the cortical bone in absorption pits in the osteolytic lesion (cyan frame). The CD68+ cells on the cortical bone reveal the infiltration of osteoclasts. The red and white scale bars on each panel indicate 10 μm and 20 μm, respectively.

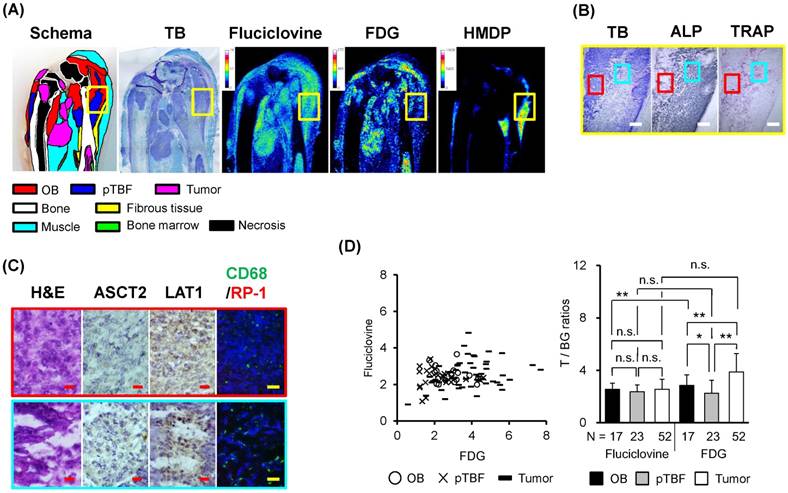

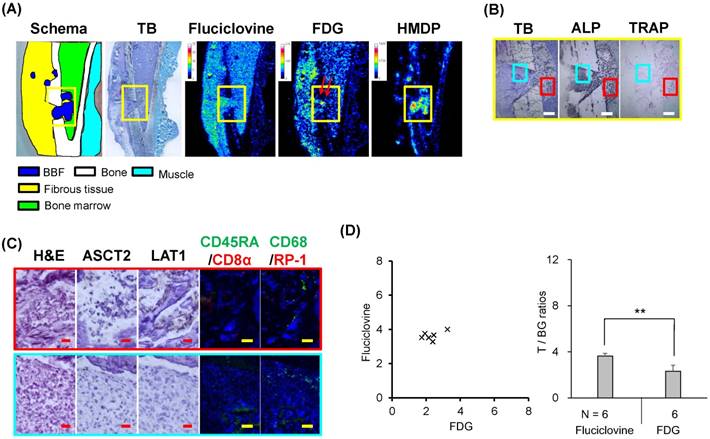

In the triple-tracer autoradiography with 14C-fluciclovine/3H-FDG/99mTc-HMDP, the distribution of 14C-fluciclovine, but not 99mTc-HMDP, was similar to that of 3H-FDG (Fig. 7A). Histological analyses demonstrated that the OB/OB lesions visually confirmed with 14C-fluciclovine and 3H-FDG accumulation (the areas corresponding to the red frames on the images in Fig. 7B), but not with 99mTc-HMDP, were primarily composed of tumor cells with positivity for LAT1, but negative to weak expression for ALP, TRAP, and ASCT2 (Fig. 7B and 7C, refer also to Fig. 8). This area also contained some CD68+-cells (i.e., monocytes/macrophages) (Fig. 7C). On the contrary, the pTBF/OB lesions with low concentrations of 14C-fluciclovine, low accumulation of 3H-FDG, and a high concentration of 99mTc-HMDP contained extensive calcification and fewer cellular components (the areas corresponding to the cyan frames on the images in Fig. 7B), although the cells in the lesion were positive for ALP and TRAP. Some cells in this area expressed ASCT2 and LAT1 (Fig. 7C). CD68+ cells were detected on the surface of the new bone as well as TRAP activity (Fig. 7C). Thus, the cellular components in the pTBF/OB lesion were probably a mixture of cancer cells, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts.

Triple-tracer autoradiography (i.e., 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-FDG, 99mTc-HMDP) and histological images in the early stage of bone metastasis in a BCa osteolytic bone metastatic model rat. (A) The schema, the TB image, and the autoradiograms of 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-FDG, and 99mTc-HMDP are shown. Color scale bars on each autoradiogram represent Bq range for each tracer. (B) The high-power microscopic images (H&E, TRAP, ASCT2, LAT1, CD45RA/CD8α, CD68/RP-1) correspond to the yellow frames on the images in Fig. 6A are shown. The existence of TRAP+ and CD68+ cells on trabeculae indicates osteolytic response. The red and yellow scale bars on each panel indicate 20 µm and 100 µm, respectively.

Triple-tracer autoradiography (i.e., 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-FDG, 99mTc-HMDP) and histological analyses in PCa osteoblastic bone metastatic model rats. (A) Macroscopic images (schema, TB) and representative autoradiograms of 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-FDG, and 99mTc-HMDP. Color scale bars on each autoradiogram represent Bq range for each tracer. (B) The low-power microscopic fields (TB, ALP, TRAP) correspond to the yellow frames on the images in Fig. 7A. Extensive osteoblastic activity is observed in TB and ALP images. The white scale bars indicate 500 μm. (C) The high-power microscopic fields (H&E, ASCT2, LAT1, CD68/RP-1) correspond to the red and cyan frames on the low-power fields in Fig. 7B. Palisade-like structures, a characteristic feature of osteoblastic lesions, are observed (H&E in the cyan frame). The red and yellow scale bars on each image indicate 20 µm and 100 µm, respectively. (D) The T/BG ratios of 14C-fluciclovine and 3H-FDG on a per-lesion basis in OB/OB, pTBF/OB, and Tumor/OB lesions. The counter plots (left) and the mean ± standard deviation (right) are shown. The numbers under each column indicate the number of lesions. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, n.s. not significant.

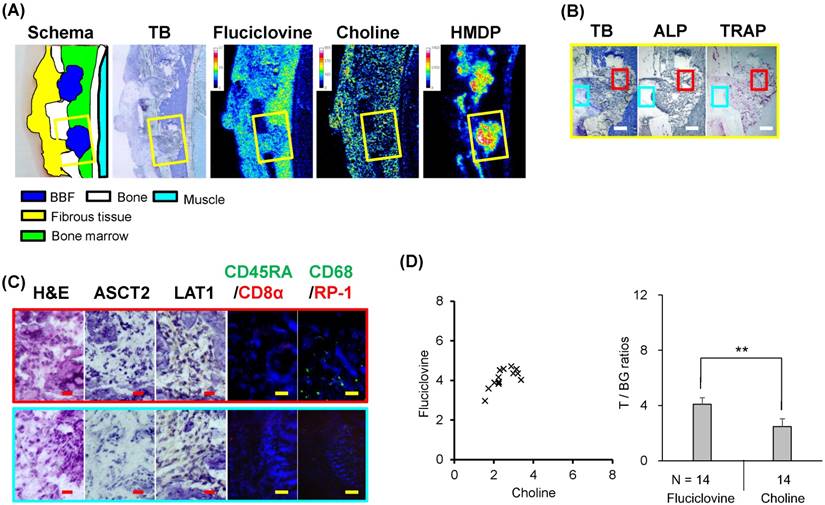

Triple-tracer autoradiography (i.e., 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-choline, 99mTc-HMDP) and histological analyses in PCa osteoblastic bone metastatic model rats. (A) Macroscopic images (schema, TB) and representative autoradiograms of 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-choline, and 99mTc-HMDP. Color scale bars on each autoradiogram represent Bq range for each tracer. (B) The low-power microscopic fields (TB, ALP, TRAP) correspond to the yellow frames on the images in Fig. 8A. The white scale bars indicate 500 μm. (C) The high-power microscopic fields (H&E, ASCT2, LAT1, CD68/RP-1) correspond to the red and cyan frames on the low-power fields in Fig. 8B. Palisade-like structures, a characteristic feature of osteoblastic lesions, are observed (H&E in the cyan frame). The red and yellow scale bars on each image indicate 20 µm and 100 µm, respectively. (D) The T/BG ratios of 14C-fluciclovine and 3H-FDG on a per-lesion basis in OB/OB, pTBF/OB, and Tumor/OB lesions. The numbers under each column indicate the number of lesions. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, n.s. not significant.

The distribution of both T/BG ratios of 14C-fluciclovine and 3H-FDG in OB/OB and pTBF/OB lesions on the counter plot were compact, although that of 3H-FDG in Tumor/OB lesions was broader than that of 14C-fluciclovine (Fig. 7D). There were statistical significant differences between each lesion for 3H-FDG, but not for 14C-fluciclovine, and between OB/OB lesions of both tracers (Fig. 7D). The detection rates (percentage) of OB/OB, pTBF/OB, and Tumor/OB lesions with T/BG ≥1.5 were 17/17 (100%), 21/23 (91.3%), and 49/52 (94.2%), respectively, with 14C-fluciclovine; and 17/17 (100%), 18/23 (78.3%), and 51/52 (98.1%), respectively, with 3H-FDG (Table 2). This finding indicated that 14C-fluciclovine had more true-positive findings than 3H-FDG at the pTBF/OB lesions. The 2 × 2 contingency table between 14C-fluciclovine and 3H-FDG showed one pTBF/OB lesion (1/23, 4.3%) and two tumor/OB lesions (2/52, 3.8%) with 14C-fluciclovine-negative/3H-FDG-positive, and four pTBF/OB lesions (4/23, 17.4%) with 14C-fluciclovine-positive/3H-FDG-negative (Table 2). Histological analysis showed that the cellular component in the lesions with 14C-fluciclovine-negative/3H-FDG-positive were primarily tumor cells, although some CD68+ cells were infiltrated. Furthermore, the lesions with 14C-fluciclovine-positive/3H-FDG-negative were typical new bone lesions with pTBF and tumor cells.

In the analyses using triple-tracer autoradiography with 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-choline, and 99mTc-HMDP, the distribution patterns of 14C-fluciclovine and 3H-choline, but not 99mTc-HMDP, were similar to each other in the OB/OB, the pTBF/OB, and Tumor/OB lesions (Fig. 8A), although the T/BG ratios of 3H-choline in the lesions were less than those of 14C-fluciclovine (Fig. 8D). The histological characteristics of the osteoblastic model used in this study were similar to those used for the autoradiography with 14C-fluciclovine/3H-FDG/99mTc-HMDP, although the pTBF/OB lesion shown in Fig. 8 appears to be more of an immature lesion than that in Fig. 7.

The detection rates (percentage) of lesions in the OB/OB, the pTBF/OB, and the Tumor/OB with T/BG ≥1.5 were 22/24 (91.7%), 27/29 (93.1%), and 47/50 (94.0%), respectively, with 14C-fluciclovine; and 12/24 (50.0%), 12/29 (41.4%), and 33/50 (66.0%), respectively, with 3H-choline (Table 2). The 2 × 2 contingency table between 14C-fluciclovine and 3H-choline showed two OB/OB (2/24, 8.3%), one pTBF/OB (1/29, 3.4%) and three Tumor/OB lesions (3/50, 6.0%) with 14C-fluciclovine-negative/3H-choline-positive, and 12 OB/OB (12/24, 50.0%), 16 pTBF/OB (16/29, 55.2%), and 17 Tumor/OB lesions (17/50, 34.0%) with 14C-fluciclovine-positive/3H-choline-negative (Table 2). These findings indicated that the accumulation and the true-positive rate of 14C-fluciclovine in the osteoblastic lesions were higher than those of 3H-choline. Histological analysis showed these discrepant lesions of the accumulation of both tracers were typical tumor tissues including some necrosis and inflammatory cells (CD68+) and typical osteoblastic tissues composed of osteoids and tumor cells; we did not find any histological differences between 14C-fluciclovine-negative/3H-choline-positive and 14C-fluciclovine-positive/3H-choline-negative lesions.

Drill-hole model

We used a DH model to investigate the accumulation of 14C-fluciclovine and 3H-FDG in the BBF without tumor cells. The accumulation of 99mTc-HMDP in the BBF/DH lesion was intense, whereas the accumulation 14C-fluciclovine and 3H-FDG was vague and not discriminated from the surrounding bone marrow (Fig. 9A). The distribution of both T/BG ratios of 14C-fluciclovine and 3H-FDG in BBF/DH lesions is shown in Fig. 9D. The accumulation of 14C-fluciclovine in the BBF was higher than that of 3H-FDG (Fig. 9D). The T/BG ratios of 14C-fluciclovine (3.6 ± 0.2) and 3H-FDG (2.3 ± 0.5) in the BBF/DH lesions were higher than (P < 0.01) and equal to (P > 0.05), respectively, those in the pTBF/OB lesions. The BBF/DH lesions contained ALP and TRAP activity (the red frames in Fig. 9B), and some LAT1+ and CD68+ cells, but not ASCT2+ cells, were on the surface of the new bones (Fig. 9C). These findings suggested that not only tumor cells but also other cells presenting in new bone regions (e.g. osteoblasts) contributed to the accumulation of 14C-fluciclovine in the pTBF/OB lesions. A relatively high accumulation of 3H-FDG, but not 14C-fluciclovine, was observed on the bone surface in the drill hole (the red arrows in a yellow frame on the autoradiograms of 3H-FDG in Fig. 9A). This finding may be caused by the infiltration of monocytes/macrophages because the cells in this area were CD68+, but TRAP- (Fig. 9B and 9C).

Triple-tracer autoradiography (i.e., 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-FDG, 99mTc-HMDP) and histological analyses in DH model rats. (A) Macroscopic images (schema, TB) and representative autoradiograms of 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-FDG, and 99mTc-HMDP. The red arrows in a yellow frame on the autoradiograms of 3H-FDG shows the region of high 3H-FDG accumulation in the drill-hole. Color scale bars on each autoradiogram represent Bq range for each tracer. (B) The low-power microscopic fields (TB, ALP, TRAP) correspond to the yellow frames on the images in Fig. 9A. Intense osteoblastic (ALP) and osteolytic (TRAP) activities are observed around the DH, showing the formation of new bones. The white scale bars indicate 500 μm. (C) The high-power microscopic fields (H&E, ASCT2, LAT1, CD45RA/CD8α, CD68/RP-1) correspond to the red and cyan frames on the low-power fields in Fig. 9B. The cells in the region showing high 3H-FDG accumulation (the red arrows in Fig. 9A) are mononuclear cells (H&E) and are positive for CD68, revealing the infiltration of monocytes/macrophages. The red and yellow scale bars on each image indicate 20 μm and 100 μm, respectively. (D) The T/BG ratios of 14C-fluciclovine and 3H-FDG on a per-lesion basis in BBF/DH lesions. The numbers under each column indicate the number of lesions. ** P < 0.01.

Triple-tracer autoradiography (i.e., 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-choline, 99mTc-HMDP) and histological analyses in DH model rats. (A) Macroscopic images (schema, TB) and representative autoradiograms of 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-choline, and 99mTc-HMDP. Color scale bars on each autoradiogram represent Bq range for each tracer. (B) The low-power microscopic fields (TB, ALP, TRAP) correspond to the yellow frames on the images in Fig. 10A. Intense osteoblastic (ALP) and osteolytic (TRAP) activities are observed around the DH, showing the formation of new bones. The white scale bars indicate 500 μm. (C) The high-power microscopic fields (H&E, ASCT2, LAT1, CD45RA/CD8α, CD68/RP-1) correspond to the red and cyan frames on the low-power fields in Fig. 10B. The red and yellow scale bars on each image indicate 20 μm and 100 μm, respectively. (D) The T/BG ratios of 14C-fluciclovine and 3H-choline on a per-lesion basis in BBF/DH lesions. The numbers under each column indicate the number of lesions. ** P < 0.01.

For the triple-tracer autoradiography with 14C-fluciclovine/3H-choline/99mTc-HMDP, the distribution patterns of tracers and the histological characteristics in the DH model used in this study were similar to those used for the autoradiography with 14C-fluciclovine/3H-FDG/99mTc-HMDP (Fig. 10). The T/BG ratios of 14C-fluciclovine (4.1 ± 0.5) and 3H-choline (2.5 ± 0.6) in the BBF/DH lesions were higher than those in the pTBF/OB lesions (P < 0.01).

Discussion

By using osteolytic and osteoblastic bone metastasis models, we histologically compared the accumulation of 14C-fluciclovine in the osteolytic and osteoblastic lesions with that of 3H-FDG and 3H-choline. The distribution patterns of these tracers were similar and their accumulations histologically corresponded to these lesions. In the osteolytic bone metastatic model, 14C-fluciclovine visualized the OL/OL lesions in bone marrow cavity as well as 18F-fluciclovine [17,18]. A typical osteolytic lesion observed in clinical specimens includes tumor cells and osteoclasts. It is reported that osteoclasts express LAT1 [31] and ASCT2 [32], which are transporters of fluciclovine [14, 16]. Thus, diagnosing osteolytic bone metastatic lesions with 18F-fluciclovine is reasonable mechanistically. In addition, 14C-fluciclovine could reveal a small osteolytic lesion in the space between trabecula at the early phase of bone metastasis. It is thought that bone absorption precedes new bone formation, even in PCa osteoblastic lesions [33]. As described above, because the 5-year survivals between cancer patients with and without bone metastases are quite different [2], early detection of bone metastasis may improve therapy outcomes and potentially increase survival. Our result indicated that 18F-fluciclovine-PET, as well as 18F-FDG-PET, may useful for the early diagnosis of osteolytic metastasis [4, 34, 35].

In the osteoblastic bone metastatic model, 14C-fluciclovine could visualize the OB/OB lesion clearer compared with 3H-FDG and 3H-choline. This result was supported by a small osteoblastic lesion adjacent to an osteolytic lesion observed in an osteolytic metastatic model (see the red frame in Fig. 5), which occurs in patients with bone metastasis [3]. Usually, a typical immature osteoblastic lesion includes osteoids, osteoblasts, and osteoclasts, in addition to tumor cells. Osteoblasts and osteoclasts express LAT1 [31], whereas osteoclasts express ASCT2 [32]. Thus, the accumulation of 14C-fluciclovine at the osteoblastic lesion may have primarily been caused by LAT1- and/or ASCT2-expressing cells such as cancer cells, osteoclasts, and osteoblasts. In addition to ASCT2 and LAT1, also some amino acid transporters (AATs) such as ASCT1 and LAT3 may be associated with 14C-fluciclovine uptake in AT6.1 cells in osteoblastic lesions because the AT6.1 cells also expressed these AATs at the gene level (Supplementary Fig. S1) and the substrates for these AATs are similar to those for ASCT2 and LAT1 [14]. Interestingly, 14C-fluciclovine vaguely visualized the OB/OB lesions, compared to the small osteoblastic lesion observed in the osteolytic metastatic model. For this reason, it may be that the latter finding indicated an immature osteoblastic lesion with abundant cell components 12 ± 1 days postinjection of the cancer cells, whereas the former finding probably indicated matured osteoblastic lesions with fewer cell components and extensive calcification 20 ± 3 days postinjection (Fig. 7B, the white stained area on the TB image indicates calcification). Regarding the abundant cellular components, the BBF lesions of the DH model 8 ± 1 days after drilling showed relative high T/BG ratios of 14C-fluciclovine. These findings suggested that 14C-fluciclovine accumulates in osteoblastic lesions but at an earlier stage of the development of osteoblastic lesions, compared to the sclerotic lesion at the late stage.

The most widely used PET tracer for diagnosing PCa is 11C-choline [6]. 11C-Choline-PET has been used for detecting osteolytic and osteoblastic metastatic lesions in patients with PCa [6]; however, Nanni et al. [36] recently reported that the T/BG ratios of 18F-fluciclovine were greater than 11C-choline in PCa relapse including bone metastasis. We also showed that 14C-fluciclovine was superior to 3H-choline for detecting lesions in osteoblastic metastasis model. In addition, Bundschuh et al. reported 11C-choline uptake corresponding to the histological localization of PCa was present in less than 50% of primary lesions [37], revealing low true-positive rating with 11C-choline as seen in the current experiment. Therefore, it seems that better image quality and contrast and the percentage of patients with true-positive findings were generally higher with 18F-fluciclovine than with 11C-choline, at least in PCa patients with osteoblastic lesions. In contrast, Beheshti et al. reported the negative correlation between 18F-fluorocholine uptake and the density of sclerotic lesions in prostate cancer patients [38]. Generally, the denser the lesion, the fewer are the tumor cells. Therefore, 18F-fluciclovine uptake may also correlate negatively with the density of sclerotic areas in osteoblastic lesions.

Our bony metastatic model showed some differential distributions of 14C-fluciclovine and 3H-FDG at the pathognomonic areas. One of the discrepant accumulation patterns of both tracers occurred in a lesion with infiltration of inflammatory cells in the osteolytic model. This lesion contained many inflammatory cells and showed low 14C-fluciclovine and high 3H-FDG accumulation. Several types of inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes, neutrophils, macrophages, dendritic cells, and mast cells exist in the tumor microenvironment [39]; however, T-lymphocytes and/or monocytes/macrophages were the main inflammatory cells infiltrating or surrounding tumor lesions in our bone metastatic models. The relatively high accumulation of 3H-FDG in the tumors with inflammation is reasonable because many non-clinical and clinical reports exist on the extensive accumulation of 18F-FDG in inflammation, which is one cause of false-positives in FDG-PET imaging [15,40,41]. Thus, a broader distribution of T/BG ratios of 3H-FDG compared to 14C-fluciclovine may indicate inflammation (Fig. 3D). However, 18F-fluciclovine is also taken up by activated lymphocytes, although the amount is smaller than that of 18F-FDG [15,41]. This finding may be because of the upregulation of LAT1 and ASCT2, which are the main AATs for fluciclovine uptake in cancer cells [14,16], along with the activation of T-lymphocytes [42,43]. This factor may cause false-positive findings in fluciclovine-PET imaging of cancer patients. In fact, few false-positives in fluciclovine-PET due to inflammation have been reported in a clinical study [36]. However, 18F-fluciclovine may have fewer false-positives, compared to FDG-PET, because of its lower uptake by inflammatory cells [15,41]. Furthermore, 18F-fluciclovine may be preferable to 18F-FDG for the evaluation of the therapeutic efficacy of chemotherapy/radiotherapy in cancer patients, because these treatments can induce an inflammatory response in cancer tissue [44], and the uptake of 18F-FDG, by inflammatory cells, especially acute inflammatory cells such as granulocytes and macrophages, is higher than that of 18F-fluciclovine [15,41]. Thus, FDG-PET may be more sensitive but less specific than fluciclovine-PET for detecting bone metastasis.

Another discrepant accumulation between 14C-fluciclovine and 3H-FDG occurred in fibrous tissue surrounding the tumor parenchyma, which invaded outside of bone marrow cavities in the BCa osteolytic metastatic model. 14C-Fluciclovine accumulated more in fibrous tissue with high ALP activity, whereas 3H-FDG accumulated more in tumor parenchyma containing necrotic tumor cells. It may be that the ALP+-cells were not derived from MRMT-1, because the BCa cells did not express ALP gene, despite expressing some osteoblastic-related genes (Supplementary Fig. S2). Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, called “cancer-associated fibroblasts,” often represent the major cellular components of the tumor stroma of primary and metastatic lesions of tumors [45]. ALP is expressed in the tumor stroma [46], LAT1 in fibroblasts [47], and ASCT2 in fibrosis [48]. Therefore, these AATs probably contributed to the accumulation of 14C-fluciclovine in the tumor stroma as well as tumor cells. If our speculation would be correct, the accumulation of 18F-fluciclovine in the tumor stroma may be a factor to increase the sensitivity of detecting cancers, especially in stroma-rich cancers such as scirrhous cancer. However, we need further investigation to demonstrate our speculation concerning the mechanisms of 18F-fluciclovine accumulation in fibrous tissue.

In the DH model, the accumulation of 14C-fluciclovine in the BBF was higher than that of 3H-FDG and 3H-choline (Fig. 9 and 10). This result suggests that the usefulness of 18F-fluciclovine may be limited, as some pathological conditions (e.g., fracture, bone infection, and arthropathy) involve osteoblastic reactions. Similar limitations have been noted for bone scan with 99mTc-MDP [4]. The BBF contained osteoblasts expressing LAT1, which explained the accumulation of 14C-fluciclovine in the BBF. Furthermore, the slow washout of 14C-fluciclovine from the BBF and normal bone marrow probably contributed to the relatively high accumulation of 14C-fluciclovine [49]. However, we have previously reported mild focal uptake of 18F-fluciclovine (milder than that of 18F-FDG) in degenerative facet disease [49]. Further clinical study is needed to investigate the possibility of false-positive results with 18F-fluciclovine in osteoblastic lesions.

In the current study, we used 14C-fluciclovine, 3H-FDG, and 3H-choline instead of 18F-fluciclovine, 18F-FDG, and 11C/18F-choline, respectively, to compare the accumulation of these tracers at the same osteolytic/osteoblastic bone metastatic lesions by using triple-tracer autoradiography technique. We believe that our findings in a rat model reflect the biomolecular changes in bone metastatic lesions of patients with PCa and BCa. However, to extrapolate our findings to clinical practice, we should keep in mind the qualitative and quantitative differences between 3H/14C- and 11C/18F-images, as well as the differences in body size (e.g., long bones, bone marrow cavity) between rats and humans.

In conclusion, 14C-fluciclovine accumulated in osteolytic lesions and osteoblastic, especially early-stage, osteoblastic bone metastatic lesions with abundant cellular components. These findings were confirmed histologically. The T/BG ratios of 14C-fluciclovine in the osteolytic model were lower than those of 3H-FDG. However, 14C-fluciclovine could more clearly reveal osteoblastic lesions. 14C-Fluciclovine was superior to 3H-choline in the osteoblastic model. Thus, 18F-fluciclovine-PET can be useful for the visualization of bone metastases in many types of cancer such as BCa and PCa. Because 99mTc-HMDP can be predominantly used for detecting advanced osteoblastic lesions (especially sclerotic bone lesions), the combined use of 18F-fluciclovine-PET and bone scan with 99mTc-HMDP would be helpful for a more accurate diagnosis of bone metastases.

Abbreviations

AAT: amino acid transporter; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; ASCT1: alanine-serine-cysteine transporter 1; ASCT2: alanine-serine-cysteine transporter 2; BBF: bland bone formation; BCa: breast cancer; 11C: carbon-11; 14C: carbon-14; CT: computed tomography; DAB: 3,3'-diaminobenzidine; DAPI: 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; DH: drill-hole; 18F: fluorine-18; FDG: 2-deoxy-2-fluoro-D-glucose; FITC: fluorescein isothiocyanate; 68Ga: gallium-68; 3H: tritium-3; H&E: hematoxylin-eosin; HBSS: Hank's balanced salt solution; HMDP: hydroxymethylene diphosphonate; IP: imaging plate; LAT1: L-type amino acid transporter 1; LAT3: L-type amino acid transporter 3; 177Lu: Lutetium-177; MDP: methylene diphosphonate; mAb: monoclonal antibody; 99mTc: technetium-99m; Nega: negative; OB: osteoblastic; OL: osteolytic; pAb: polyclonal antibody; PE: phycoerythrin; PET: positron emission tomography; Posi: positive; PCa: prostate cancer; PSMA: prostate-specific membrane antigen; pTBF: peri-tumor bone formation; RCP: radiochemical purity; RMPI1640: Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640; ROI: region-of-interest; SCEM: super-cryo embedding medium: SR: super resolution screen: TB: toluidine blue: T/BG: targetmean-to-backgroundmean: TR: tritium screen; TRAP: tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures and tables.

Acknowledgements

We thank Masahiro Ono for his assistance in the histological examinations and computed tomography imaging; Sachiko Naito for her assistance in the daily maintenance of the cell cultures and reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction; Shiro Yoshida for his assistance in the daily maintenance of the animals; and our colleagues for their comments on the manuscript. We thank Editage for English editing.

Ethics

All animal handling and experimentation procedures were conducted in accordance with the Japanese Laws for Act on Welfare and Management of Animals and approved by the Committee on Animal Welfare at Nihon Medi-Physics.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Shuntaro Oka, Masaru Kanagawa

Development of methodology: Shuntaro Oka, Masaru Kanagawa

Acquisition of data: Shuntaro Oka, Masaru Kanagawa, Yoshihiro Doi

Analysis and interpretation of data (e.g., histological analysis, statistical analysis): Shuntaro Oka

Writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: Shuntaro Oka, Masaru Kanagawa, Yoshihiro Doi, David M. Schuster, Mark M. Goodman, Hirokatsu Yoshimura

Administrative, technical, or material support: David M. Schuster, Mark M. Goodman, Hirokatsu Yoshimura

Study supervision: Hirokatsu Yoshimura

Conflict of interest

Shuntaro Oka, Masaru Kanagawa, Yoshihiro Doi, and Hirokatsu Yoshimura are employees of Nihon Medi-Physics (Tokyo, Japan). We are collaborating with Mark M. Goodman and David M. Schuster for nonclinical and clinical studies on 18F-fluciclovine. Mark M. Goodman and Emory University are eligible to receive royalties from Nihon Medi-Physics. David M. Schuster is receiving research support through Emory University from Nihon Medi-Physics and Blue Earth Diagnostics (Oxford, United Kingdom). There is no other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article to declare.

References

1. Li S, Peng Y, Weinhandl ED. et al. Estimated number of prevalent cases of metastatic bone disease in the US adult population. Clin Epidemiol. 2012;4:87-93

2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5-29

3. Guise TA, Mohammad KS, Clines G. et al. Basic mechanisms responsible for osteolytic and osteoblastic bone metastases. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6213s-6s

4. Peterson JJ, Kransdorf MJ, O'Connor MI. Diagnosis of occult bone metastases: positron emission tomography. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;415(Suppl):S120-S128

5. Nakai T, Okuyama C, Kubota T. et al. Pitfalls of FDG-PET for the diagnosis of osteoblastic bone metastases in patients with breast cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:1253-8

6. Mapelli P, Incerti E, Ceci F. et al. 11C- or 18F-Choline PET/CT for imaging evaluation of biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:43S-48S

7. Schwarz T, Seidl C, Schiemann M. et al. Increased choline uptake in macrophages and prostate cancer cells does not allow for differentiation between benign and malignant prostate pathologies. Nucl Med Biol. 2016;43:355-9

8. Azad GK, Cook GJ. Multi-technique imaging of bone metastases: spotlight on PET-CT. Clin Radiol. 2016;71:620-31

9. Schuster DM, Nanni C, Fanti S. PET Tracers Beyond FDG in Prostate Cancer. Semin Nucl Med. 2016;46:507-521

10. Houssami N, Costelloe CM. Imaging bone metastases in breast cancer: evidence on comparative test accuracy. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:834-43

11. Hildebrandt MG, Gerke O, Baun C. et al. [18F]Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) in suspected recurrent breast cancer: a prospective comparative study of dual-time-point FDG-PET/CT, contrast-enhanced CT, and bone scintigraphy. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1889-97

12. Wondergem M, van der Zant FM, van der Ploeg T. et al. A literature review of 18F-fluoride PET/CT and 18F-choline or 11C-choline PET/CT for detection of bone metastases in patients with prostate cancer. Nucl Med Commun. 2013;34:935-45

13. Shen G, Deng H, Hu S. et al. Comparison of choline-PET/CT, MRI, SPECT, and bone scintigraphy in the diagnosis of bone metastases in patients with prostate cancer: a meta-analysis. Skeletal Radiol. 2014;43:1503-13

14. Oka S, Okudaira H, Yoshida Y. et al. Transport mechanisms of trans-1-amino-3-fluoro[1-14C]cyclobutanecarboxylic acid in prostate cancer cells. Nucl Med Biol. 2012;39:109-19

15. Oka S, Okudaira H, Ono M. et al. Differences in transport mechanisms of trans-1-amino-3-[18F]fluorocyclobutanecarboxylic acid in inflammation, prostate cancer, and glioma cells: comparison with L-[methyl-11C]methionine and 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose. Mol Imaging Biol. 2014;16:322-9

16. Okudaira H, Nakanishi T, Oka S. et al. Kinetic analyses of trans-1-amino-3-[18F]fluorocyclobutanecarboxylic acid transport in Xenopus laevis oocytes expressing human ASCT2 and SNAT2. Nucl Med Biol. 2013;40:670-5

17. Schuster DM, Savir-Baruch B, Nieh PT. et al. Detection of recurrent prostate carcinoma with anti-1-amino-3-18F-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid PET/CT and 111In-capromab pendetide SPECT/CT. Radiology. 2011;259:852-61

18. Amzat R, Taleghani P, Savir-Baruch B. et al. Unusual presentations of metastatic prostate carcinoma as detected by anti-3 F-18 FACBC PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2011;36:800-2

19. Suzuki H, Inoue Y, Fujimoto H. et al. Diagnostic performance and safety of NMK36 (trans-1-amino-3-[18F]fluorocyclobutanecarboxylic acid)-PET/CT in primary prostate cancer: multicenter Phase IIb clinical trial. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2016;46:152-62

20. Tade FI, Cohen MA, Styblo TM. et al. Anti-3-18F-FACBC (18F-Fluciclovine) PET/CT of breast cancer: an exploratory study. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:1357-63

21. Ulaner GA, Goldman DA, Gönen M. et al. Initial results of a prospective clinical trial of 18F-fluciclovine PET/CT in newly diagnosed invasive ductal and invasive lobular breast cancers. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:1350-6

22. Shoup TM, Olson J, Hoffman JM. et al. Synthesis and evaluation of [18F]1-amino-3-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid to image brain tumors. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:331-8

23. Kondo A, Ishii H, Aoki S. et al. Phase IIa clinical study of [18F]fluciclovine: efficacy and safety of a new PET tracer for brain tumors. Ann Nucl Med. 2016;30:608-18

24. Jani AB, Fox TH, Whitaker D. et al. Case study of anti-1-amino-3-F-18 fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid (anti-[F-18] FACBC) to guide prostate cancer radiotherapy target design. Clin Nucl Med. 2009;34:279-84

25. Jani AB, Schreibmann E, Rossi PJ. et al. Impact of 18F-fluciclovine PET on target volume definition for postprostatectomy salvage radiotherapy: initial findings from a randomized trial. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:412-8

26. Akin-Akintayo OO, Jani AB, Odewole O. et al. Change in salvage radiotherapy management based on guidance with FACBC (fluciclovine) PET/CT in postprostatectomy recurrent prostate cancer. Clin Nucl Med. 2017;42:e22-8

27. Greco C, Forte L, Erba P. et al. Bone metastases, general and clinical issues. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;55:337-52

28. Zepp M, Bäuerle TJ, Elazar V, et al. Treatment of breast cancer lytic skeletal metastasis using a model in nude rats. In: Gunduz E, editor. Breast cancer—current and alternative therapeutic modalities. InTech; 2011. DOI: 10.5772/24269. http://www.intechopen.com/books/breast-cancer-current-and-alternative-therapeutic-modalities/treatment-of-breast-cancer-lytic-skeletal-metastasis-using-a-model-in-nude-rats

29. Kawamoto T. Use of a new adhesive film for the preparation of multi-purpose fresh-frozen sections from hard tissues, whole-animals, insects and plants. Arch Histol Cytol. 2003;66:123-43

30. Obata T, Iwamoto K, Shiraiwa Y. et al. Instruments for radiation measurement in biosciences. Series 3. Radioluminography. 17. Analysis of double-labelled samples by the imaging plate (IP). Radioisotopes. 2000;49:623-36

31. Kim SG, Ahn YC, Yoon JH. et al. Expression of amino acid transporter LAT1 and 4F2hc in the healing process after the implantation of a tooth ash and plaster of Paris mixture. In Vivo. 2006;20:591-7

32. Indo Y, Takeshita S, Ishii KA. et al. Metabolic regulation of osteoclast differentiation and function. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:2392-9

33. Yonou H, Ochiai A, Goya M. et al. Intraosseous growth of human prostate cancer in implanted adult human bone: relationship of prostate cancer cells to osteoclasts in osteoblastic metastatic lesions. Prostate. 2004;58:406-13

34. Morris MJ, Akhurst T, Osman I. et al. Fluorinated deoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging in progressive metastatic prostate cancer. Urology. 2002;59:913-8

35. Ozcan Kara P, Kara T, Kara Gedik G. et al. Comparison of bone scintigraphy and 18F-FDG PET-CT in a prostate cancer patient with osteolytic bone metastases. Rev Esp Med Nucl. 2011;30:94-6

36. Nanni C, Zanoni L, Pultrone C. et al. 18F-FACBC (anti1-amino-3-18F-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid) versus 11C-choline PET/CT in prostate cancer relapse: results of a prospective trial. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43:1601-10

37. Bundschuh RA, Wendl CM, Weirich G. et al. Tumour volume delineation in prostate cancer assessed by [11C]choline PET/CT: validation with surgical specimens. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:824-31

38. Beheshti M, Vali R, Waldenberger P. et al. Detection of bone metastases in patients with prostate cancer by 18F fluorocholine and 18F fluoride PET-CT: a comparative study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:1766-74

39. Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883-99

40. Shreve PD, Anzai Y, Wahl RL. Pitfalls in oncologic diagnosis with FDG PET imaging: physiologic and benign variants. Radiographics. 1999;19:61-77

41. Kanagawa M, Doi Y, Oka S. et al. Comparison of trans-1-amino-3-[18F]fluorocyclobutanecarboxylic acid (anti-[18F]FACBC) accumulation in lymph node prostate cancer metastasis and lymphadenitis in rats. Nucl Med Biol. 2014;41:545-51

42. Hayashi K, Jutabha P, Endou H. et al. LAT1 is a critical transporter of essential amino acids for immune reactions in activated human T cells. J Immunol. 2013;191:4080-5

43. Nakaya M, Xiao Y, Zhou X. et al. Inflammatory T cell responses rely on amino acid transporter ASCT2 facilitation of glutamine uptake and mTORC1 kinase activation. Immunity. 2014;40:692-705

44. Sciarra A, Gentilucci A, Salciccia S. et al. Prognostic value of inflammation in prostate cancer progression and response to therapeutic: a critical review. J Inflamm (Lond). 2016;13:35

45. Öhlund D, Elyada E, Tuveson D. Fibroblast heterogeneity in the cancer wound. J Exp Med. 2014;211:1503-23

46. Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, Maltezos E. et al. Down-regulation of intestinal-type alkaline phosphatase in the tumor vasculature and stroma provides a strong basis for explaining amifostine selectivity. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:14-21

47. Vumma R, Wiesel FA, Flyckt L. et al. Functional characterization of tyrosine transport in fibroblast cells from healthy controls. Neurosci Lett. 2008;434:56-60

48. Larriba S, Sumoy L, Ramos MD. et al. ATB(0)/SLC1A5 gene. Fine localisation and exclusion of association with the intestinal phenotype of cystic fibrosis. Eur J Hum Genet. 2001;9:860-6

49. Schuster DM, Nanni C, Fanti S. et al. Anti-1-amino-3-18F-fluorocyclobutane-1-carboxylic acid: physiologic uptake patterns, incidental findings, and variants that may simulate disease. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:1986-92

Author contact

![]() Corresponding author: Shuntaro Oka, D.V.M., Ph.D., Research Center, Nihon Medi-Physics Co. Ltd., Kitasode 3-1, Sodegaura, Chiba 299-0266, Japan Phone: +81-438-62-7611 Fax: +81-438-62-5911 E-mail: shuntaro_okaco.jp

Corresponding author: Shuntaro Oka, D.V.M., Ph.D., Research Center, Nihon Medi-Physics Co. Ltd., Kitasode 3-1, Sodegaura, Chiba 299-0266, Japan Phone: +81-438-62-7611 Fax: +81-438-62-5911 E-mail: shuntaro_okaco.jp

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact