13.3

Impact Factor

Theranostics 2026; 16(9):4657-4701. doi:10.7150/thno.124716 This issue Cite

Review

Panoramic description of ROS-based nanotechnology for osteomyelitis therapy: Challenges, opportunities, and prospects

1. Department of Spine Surgery, The Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao 266700, China.

2. Institute of Regenerative Medicine and Laboratory Technology Innovation, Qingdao University, Qingdao 266071, China.

3. Qingdao Key Lab of Common Diseases, University of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Qingdao Municipal Hospital, Qingdao 266071, China.

Received 2025-9-5; Accepted 2026-1-13; Published 2026-2-11

Abstract

Osteomyelitis, an inflammatory disease of bone and bone marrow caused by infectious microorganisms, has long been a major clinical challenge due to the lack of consistently effective treatment strategies. Conventional therapeutic approaches, such as antibiotic therapy and surgical debridement, are frequently associated with the development of antibiotic resistance and a high risk of disease recurrence, thereby complicating long-term clinical management. In recent years, reactive oxygen species (ROS)-based nanotechnology has emerged as a promising therapeutic modality for osteomyelitis, garnering considerable attention for the potential to overcome antibiotic resistance. This review summarizes the epidemiological characteristics, current treatment approaches, and pathogenic mechanisms of osteomyelitis, and comprehensively examines advances in ROS nanotechnologies for osteomyelitis treatment. In addition, the technical advantages and limitations of major ROS-based strategies, including photodynamic therapy (PDT), sonodynamic therapy (SDT), chemodynamic therapy (CDT), and microwave dynamic therapy (MWDT), are systematically discussed to provide guidance for further optimization of ROS-mediated strategies. Furthermore, the therapeutic potential of these strategies in antimicrobial activity, promotion of tissue repair, and immune regulation is analyzed, offering theoretical support for the integration of ROS-based strategies with existing treatment modalities for improved management of osteomyelitis.

Keywords: osteomyelitis, reactive oxygen species, nanomaterials, nanotechnology

Introduction

Osteomyelitis is widely recognized as an inflammatory disease of bone and bone marrow caused by infectious microorganisms and is closely associated with local bone destruction, necrosis, and impaired new bone formation [1]. The reported annual incidence of osteomyelitis ranges from approximately 4.8 to 21.8 cases per 100,000 population [2]. Considerable variation in incidence exists across different populations and geographic regions, largely influenced by factors such as age distribution, underlying comorbidities, prevalence of diabetes, frequency of post-traumatic and post-operative infections, and regional sanitary conditions [3]. Although the incidence of acute osteomyelitis has declined in many developed countries as a result of improvements in public health measures and nutritional support, higher rates continue to be observed in several developing regions, particularly in parts of Africa, where urbanization and increased motor vehicle use have contributed to a rising number of open injuries [4]. Fracture internal fixation and joint replacement represent common sources of infection leading to osteomyelitis, while elderly individuals with diabetes, neurological disorders, or peripheral vascular disease are at increased risk of developing chronic disease, with approximately 20% of patients with diabetic foot ulcers progressing to osteomyelitis [5]. Despite advances in medical care that have reduced the occurrence of acute infection, the incidence of chronic osteomyelitis continues to increase as a consequence of population aging, a growing number of high-energy traumatic injuries, and the expanding volume of orthopedic surgical procedures [6]. Bone infection following open fractures and periprosthetic joint infection after arthroplasty often progress to chronic osteomyelitis, imposing a substantial financial burden on affected individuals due to prolonged hospitalization and complex treatment requirements [7]. In severe cases, treatment failure may ultimately result in limb amputation or mortality. Consequently, the effective eradication of infection and prevention of disease recurrence have emerged as critical research priorities in the contemporary management of chronic osteomyelitis.

At present, clinically accepted treatment for osteomyelitis remains largely dependent on antibiotic therapy and surgical intervention. Excessive and prolonged use of antibiotics has led to the rapid emergence of antimicrobial resistance and the increasing prevalence of multidrug-resistant bacterial infections. Although surgical debridement enables prompt removal of necrotic and infected tissue, complete eradication of resistant microorganisms remains difficult, thereby increasing the likelihood of disease recurrence [8]. Extensive efforts have therefore been directed towards addressing antibiotic overuse and recurrent infection in osteomyelitis management, including the development of novel antimicrobial agents and improvements in surgical techniques and diagnostic strategies; however, clinical outcomes remain suboptimal [9]. With recent advances in nanomedicine, reactive oxygen species (ROS)-based nanotechnology has emerged as a promising therapeutic approach for chronic osteomyelitis, demonstrating broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity and effective suppression of drug-resistant and multi drug-resistant pathogens [10].

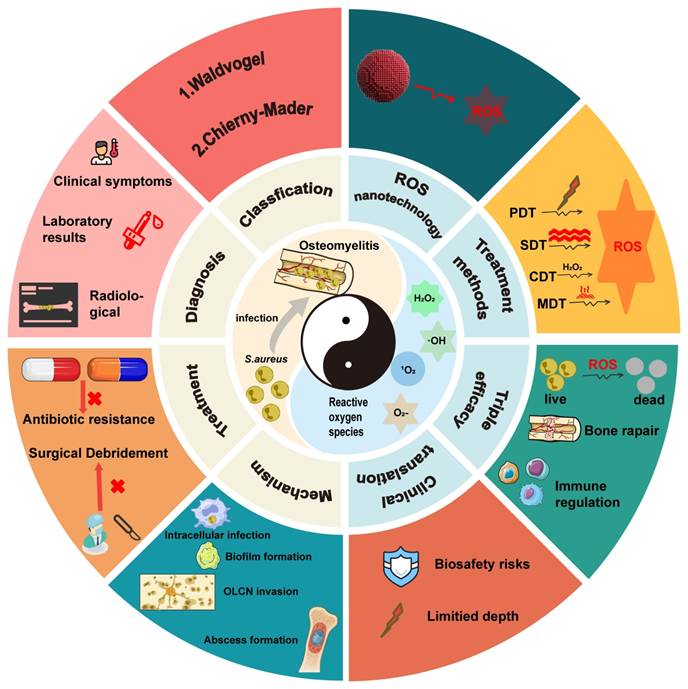

This review provides a comprehensive and systematic discussion of the clinical classification, pathogenesis, diagnostic techniques, and current treatment strategies for osteomyelitis. Particular emphasis is placed on the mechanisms by which Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), one of the primary causative agents, facilitates persistent infection and immune evasion at the site of infection, thereby contributing to refractory chronic osteomyelitis. Recent progress in ROS-based nanotechnologies for osteomyelitis treatment is subsequently examined in detail. The technical advantages and inherent limitations of major ROS-mediated strategies, including photodynamic therapy (PDT), sonodynamic therapy (SDT), chemodynamic therapy (CDT), and microwave dynamic therapy (MWDT), are analyzed to provide direction for further optimization. In addition, the therapeutic potential of these approaches in antimicrobial activity, enhancement of tissue repair, and modulation of immune responses is evaluated, offering theoretical support for the integration of ROS-based strategies with existing treatment modalities. Finally, current challenges and future prospects of ROS-based nanotechnology in osteomyelitis therapy are discussed to provide a comprehensive overview of emerging treatment strategies and their potential clinical significance (Figure 1).

Although recent studies have reported the application of ROS-based technologies in the treatment of bone infections, optimization strategies and combination approaches specifically designed for osteomyelitis, together with clearly defined therapeutic mechanisms, remain insufficiently summarized. Furthermore, the development of ROS technologies tailored to the unique pathological microenvironment of osteomyelitis has received limited attention. Within this context, the present review contributes in three major aspects. First, a comprehensive and critical panoramic analysis of ROS nanotechnologies, including PDT, SDT, CDT, and MWDT, is provided, with particular emphasis on multimodal integration strategies to overcome the limitations of single-modality approaches. Second, beyond the direct antimicrobial effects mediated through disruption of microbial cellular structures, the pivotal role of ROS-based approaches in modulating the immunosuppressive bone microenvironment and their synergistic interactions with bone regeneration strategies are systematically elucidated, leading to the proposal of an integrated triple-therapy framework encompassing anti-infection, immune-regulation, and bone-repair as a comprehensive paradigm for osteomyelitis management. Third, critical challenges and future directions for the clinical translation of ROS nanotechnologies are thoughtfully examined, including considerations of material biosafety, targeting efficiency, rational combination therapy design, and translational feasibility. Collectively, this review provides timely and distinctive guidance for researchers and clinicians pursuing innovative therapeutic strategies for osteomyelitis beyond conventional antibacterial approaches.

Osteomyelitis

Pathogenic mechanism of S. aureus in osteomyelitis

Owing to the remarkable capacity for invasion, colonization, and proliferation within bone tissue, S. aureus exhibits distinct pathogenic behavior during skeletal infection. The major mechanisms underlying persistent osteomyelitis include intracellular infection, formation of staphylococcal abscess communities (SACs), invasion of the osteocyte lacuno-canalicular network (OLCN), and biofilm formation [11]. Systematic analysis of these mechanisms not only clarifies the specific pathway by which S. aureus invades and colonizes bone tissue but also provides a conceptual foundation for the development of novel therapeutic strategies for refractory osteomyelitis.

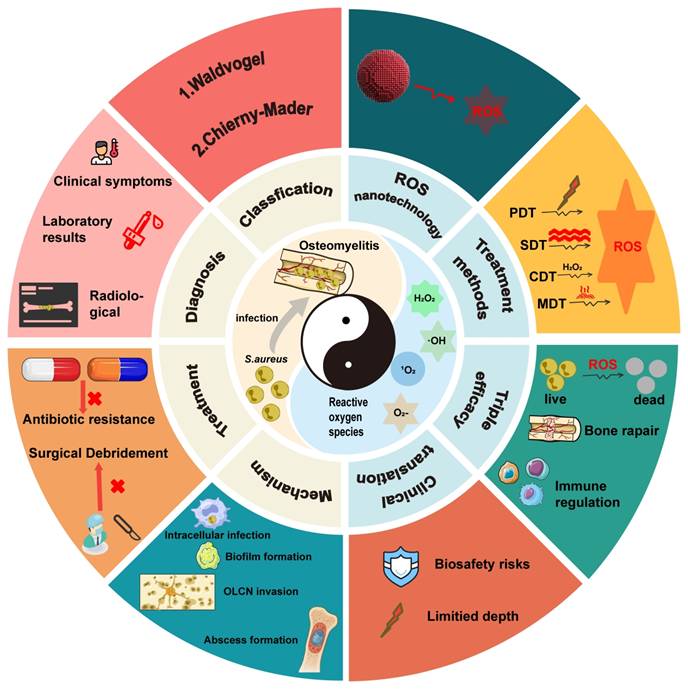

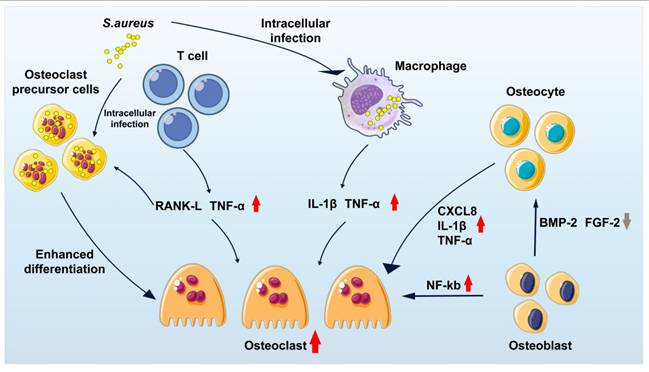

Intracellular infection: Intracellular infection represents a central mechanism contributing to the persistence and recurrence of osteomyelitis, as S. aureus is capable of long-term survival in a dormant state within host cells. Multiple cell types, including macrophages, endothelial cells, keratinocytes, and epithelial cells, have been shown to harbor intracellular S. aureus [12-14]. Infection of macrophages is particularly associated with chronic osteomyelitis. These infected macrophages, often described as "Trojan horse" macrophages, facilitate systemic bacterial dissemination, promote the enrichment of small colony variants (SCV), and attenuate host inflammatory responses [14]. Such phenotypic adaptation enables S. aureus to evade immune surveillance and constitutes a major driver of chronic and recurrent infection. In addition, S. aureus is capable of invading osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and osteocytes (Figure 2), where intracellular persistence eventually leads to host cell apoptosis or sustained intracellular infection, further perpetuating disease progression [15-26].

Schematic illustration of the application of reactive oxygen species-based nanotechnology in the treatment of osteomyelitis. The figure summarizes the principal components addressed in this review, including the pathological microenvironment of osteomyelitis, major ROS-mediated therapeutic strategies (PDT, SDT, CDT, and MWDT), and their core functions in antibacterial activity, immune regulation, and bone regeneration.

Summary diagram illustrating the responses of osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and osteocytes in the presence of S. aureus.

Formation of SACs: S. aureus can achieve effective self-protection within the host microenvironment through the formation of specialized protective barriers, gradually developing into SACs that inhibit immune cell attack and facilitate bacterial survival and dissemination [27]. SACs, representing abscess structures associated with low- virulence bacterial infection, are mainly found within the bone marrow cavity of the long bones in pediatric patients. Structurally, SACs consist of a central bacterial community surrounded a fibrin-rich pseudocapsule and infiltrating immune cells, a configuration that confers high bacterial viability and substantial resistance to both antibiotic treatment and host immune defenses [28]. SAC formation is governed by complex regulatory signaling pathways. Initially, S. aureus activates coagulase (CoA) and von Willebrand factor-binding protein (vWFbp), which bind to and activate prothrombin, thereby promoting the formation of protective fibrin pseudocapsules [29]. Subsequently, clumping factor A (ClfA) and clumping factor B (ClfB) interact with fibrinogen, enabling the pathogen to evade phagocytic recognition and contributing critically to SAC development [30]. In parallel, S. aureus secretes immune evasion proteins, such as Staphylococcal chemoattractant proteins (CHIPS) and Staphylococcal complement inhibitors (SCIN), which suppress acute immune responses [31]. Furthermore, S. aureus induces destruction of neutrophils recruited to the abscess community, generating cellular debris that paradoxically forms an additional physical barrier, thereby preventing subsequent infiltration of host defense cells and further enhancing bacterial persistence [32].

Formation of Biofilm: Biofilms are organized microbial communities that adhere to tissue surfaces or biomaterial interfaces and represent one of the most prevalent complications in orthopedic infections. The surfaces of commonly used orthopedic materials, such as titanium and its alloys, stainless steel, cobalt-chromium alloys, polymeric materials, and polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) bone cement, provide favorable substrates for biofilm development. Biofilm formation by S. aureus at sites of bone injury significantly restricts the penetration of antibiotics and immune cells, thereby promoting persistent infection [33]. Biofilm development generally proceeds through sequential stages of bacterial attachment, accumulation, and dispersion within host tissues [34-35]. Bacteria released from mature biofilms secrete a broad range of virulence factors, including coagulase, lipase, hyaluronidase, and protein A (SpA), which play important roles in disease progression and osteomyelitis pathogenesis. Among these, toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 (TSST-1), alpha-hemolysin (Hla), and Pantone-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) have been shown to significantly exacerbate osteomyelitis. TSST-1, a potent superantigen that suppresses plasma cell differentiation and antibody responsiveness, markedly inhibits host immune function and induces elevated expression of cytokines associated with toxic shock syndrome, including IFN-γ, TNF, IL-2, and IL-6 [36]. Furthermore, TSST-1 has been demonstrated to enhance osteoclast-mediated bone resorption and accelerate bone tissue destruction [37]. Hla, a secreted cytotoxin synthesized by many S. aureus strains, disrupts early neutrophil recruitment by impairing calcium signaling and calcium-dependent leukotriene B4 (LTB4) production [38]; however, Hla expression is downregulated during persistent bone infection, contributing to bacterial quiescence and the latent nature of recurrent osteomyelitis [39]. PVL, produced by a limited subset of S. aureus strains, lyses leukocytes through membrane disruption and is strongly associated with rapid disease progression and sustained infection [40]. In addition, S. aureus-derived coagulase promotes biofilm stabilization by converting fibrinogen into fibrin, thereby generating a protective barrier that shields bacteria from immune attack. Coagulase further contributes to bone destruction by inhibiting osteoblast proliferation, inducing apoptosis, and reducing mineralization, ultimately aggravating bone loss during infection [41].

OLCN invasion: Invasion of the OLCN by S. aureus represents another critical mechanism underlying the persistence of osteomyelitis, enabling the pathogen to evade host defenses more effectively and substantially increasing the risk of recurrence following treatment of refractory osteomyelitis [11]. Emerging evidence indicates that S. aureus can penetrate cortical bone and persist within the OLCN, a process attributed in part to the remarkable deformability of the bacterial cells [42]. Using transmission electron microscopy (TEM), de Mesy et al. directly visualized the invasion and colonization of cortical bone by S. aureus and demonstrated that the bacteria are capable of deforming to diameters of approximately 0.5 µm to facilitate migration through sub micron bone channels [43]. Consistent with these findings, bacterial deformation and infiltration of the OLCN were subsequently observed in lesion samples from patients with infectious diabetic foot ulcers complicated by chronic S. aureus osteomyelitis [44]. Notably, clinical reports describing reactivation of infection 50 to 75 years after the initial episode further support the capacity of S. aureus for long-term persistence within bone tissue, likely mediated by submicron deformation and slow metabolic activity of S. aureus within the osteocellular canicular system [45-47].

Traditional treatments for osteomyelitis

Effective management of osteomyelitis and prevention of disease recurrence require a comprehensive, interdisciplinary treatment approach encompassing thorough patient evaluation, appropriate antimicrobial therapy, and necessary surgical intervention. Selection of specific treatment modalities is influenced by multiple factors, such as disease pathogenesis, anatomical site, presence of orthopedic implants, and host-pathogen interactions, resulting in significant interindividual variability. Despite these differences, the core objectives of osteomyelitis management remain consistent, namely the eradication of local infection and control of systemic dissemination [48]. This section provides a systematic overview of conventional antibiotic-based and surgical treatment strategies, together with an analysis of their inherent limitations, with the aim of informing optimization of current therapeutic approaches and identifying potential directions for future development.

Antibiotic therapy: Antibiotic administration remains essential in the treatment of osteomyelitis, regardless of whether surgical debridement is performed [49]. Systemic antimicrobial therapy constitutes an important component of disease management, with empirical broad-spectrum antibiotics typically initiated prior to the availability of microbiological culture and sensitivity results. Owing to the high likelihood of rapid resistance development with monotherapy, combination antibiotic regimens are commonly employed when formulating clinical treatment plans [50]. Despite widespread clinical use, systemic antibiotic therapy is associated with substantial limitations. Prolonged high-dose exposure frequently increases the risk of multi-organ toxicity, while long-term treatment contributes to the development of irreversible antimicrobial resistance. The clinical application of local antibiotic delivery for osteomyelitis remains controversial [51-54], and existing localized strategies face additional challenges, including suboptimal drug release kinetics, limited biocompatibility, and the need for secondary surgical procedures.

Surgical Treatment: Surgical management of osteomyelitis is primarily directed toward thorough debridement of infected tissue, reconstruction of bone and soft tissue defects, and prevention of associated complications. In chronic osteomyelitis, debridement typically involves removal of inflammatory tissue, sinus tracts, scar tissue, infected granulation tissue, medullary abscesses, sclerotic bone, and necrotic bone. Clinical outcomes following surgical intervention are strongly influenced by anatomical location, integrity of surrounding soft tissues, presence of orthopedic implants, formation of deep abscesses or biofilms, and host immune status, resulting in considerable interpatient variability [55]. Osteomyelitis associated with diabetic foot infection presents particular therapeutic challenges, often accompanied by severe soft tissue infection, neuroarthritic osteoarthropathy, and compromised vascular supply, which collectively contribute to suboptimal treatment outcomes [56-57]. Consequently, patients with metabolic disorders require highly individualized therapeutic strategies. Moreover, even after technically successful surgical intervention, osteomyelitis remains associated with a substantial risk of recurrence, underscoring the need for adjunctive technologies capable of achieving complete eradication of residual microorganisms while simultaneously promoting restoration of the local microenvironment.

Other Treatments: Hyperbaric oxygen therapy has shown unique therapeutic advantages in the treatment of osteomyelitis. The antibacterial effect of hyperbaric oxygen in osteomyelitis is thought to be closely related to enhanced formation of ROS [58]. In addition, hyperbaric oxygen therapy reduces localized pathogen burden through activation of host immune responses and synergistic interaction with antimicrobial agents, while its anti-inflammatory properties further contribute to the attenuation of bone tissue injury and infection [59]. Beyond oxygen-based approaches, growth factor- and gene-based strategies have also been explored for osteomyelitis treatment. Aliyev et al. demonstrated that vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) gene-transfected muscle flaps significantly reduced abscess formation and bone necrosis by inhibiting disease progression and promoting local blood supply, supporting the development of molecular therapies for osteomyelitis [60]. Moreover, a growing number of emerging technologies have reported considerable potential for the treatment of infectious diseases [61-66], among which ROS-based antimicrobial strategies represent particularly promising therapeutic candidates [67].

Application of ROS nanotechnology in osteomyelitis

In recent years, ROS-based antibacterial nanotechnology has attracted increasing attention in the clinical management of osteomyelitis due to its potent antimicrobial efficacy and low propensity for inducing drug resistance. The core mechanism underlying ROS-mediated antibacterial nanotechnology involves exploitation of the physicochemical properties of nanomaterials to generate ROS, thereby disrupting the redox homeostasis of microbial cells and ultimately inducing cell death. This section systematically examines the potential advantages and therapeutic applications of ROS-based antibacterial nanotechnology in osteomyelitis treatment, with the aim of providing valuable insights for the development of next-generation anti-osteomyelitis therapies.

Overview of ROS

ROS are highly reactive and unstable oxygen-derived molecules generated as byproducts of cellular oxygen metabolism, primarily within organelles such as mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, and peroxisomes. Major ROS species include free radicals such as superoxide anion (·O2-), hydroxyl radical (·OH), hydroperoxyl radical (·HOO), carbonate radical (·CO3-), and carbon dioxide radical (·CO2-), as well as non-radical oxidants including singlet oxygen (1O2), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hypobromous acid (HOBr), and hypochlorous acid (HOCl) [68].

Acting as critical intracellular signaling mediators, ROS regulate multiple canonical signaling pathways involved in inflammation and infection. ROS activate upstream kinases of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade, including c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and extracellular regulatory protein kinase (ERK), thereby promoting activation of the transcription factor AP-1 and inducing expression of genes related to cell proliferation, survival and inflammatory responses [69]. Accumulation of ROS further amplifies phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt) signaling, thereby enhancing downstream pathways that support cellular survival and proliferation. Sustained ROS production also maintains continuous activation of the JAK/STAT pathway by stimulating Janus kinases and inhibiting protein phosphatases such as SHP-2, ultimately driving transcription of inflammation-related genes [69]. Within the nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling network, ROS often act as second messengers, oxidizing NF-κB directly or modifying key cysteine residues on IκB, thereby promoting dissociation of the NF-κB-IκB complex and promoting NF-κB nuclear translocation, which culminates in the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines [70]. In parallel, ROS modulate the antioxidant response through activation of the Nrf2 pathway. Oxidative modification of key cysteine residues on Keap1 leads to Nrf2 release and nuclear translocation, thereby initiating the transcription of antioxidant enzyme, including heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1), to counterbalance oxidative stress. Dysregulation of these interconnected pathways has been observed in chronic inflammatory and infectious conditions, where excessive ROS simultaneously hyperactivate pro-inflammatory cascades such as MAPK, NF-κB, and PI3K/Akt while suppressing Nrf2-mediated antioxidant defenses, thereby driving amplification of tissue-destructive inflammatory responses [69].

Substantial endogenous production of ROS at sites of infection induces oxidative stress and triggers amplification of pro-inflammatory signaling pathways, including MAPK, NF-κB, and NLRP3, thereby reshaping the local microenvironment in osteomyelitis [69,70]. This pathological microenvironment is characterized by persistent inflammation, enhanced cellular apoptosis, and increased bone resorption. The elevated ROS levels within infected bone tissue provide valuable molecular targets for diagnostic applications. For instance, ROS-responsive fluorescent and photoacoustic probes can be selectively "illuminated" within inflamed bone tissues, aiding early lesion localization and dynamic monitoring of disease progression.

Osteomyelitis lesions are further distinguished by persistent microbial colonization and biofilm formation accompanied by immune suppression or dysfunction. ROS exert direct antimicrobial effects by inducing lipid peroxidation and damaging microbial proteins and nucleic acids, thereby serving as a non-antibiotic, broad-spectrum antimicrobial mechanism. Concurrently, physiologically moderate ROS signaling modulates immune responses by activating or reprogramming immune cells. Experimental evidence indicates that ROS promote macrophage polarization toward the M1 phenotype, enhancing bactericidal activity, and enhancing adaptive immune responses through regulation of T-cell activation.

At low to moderate concentrations, ROS promote angiogenesis, osteoblast proliferation and differentiation, and tissue regeneration. In contrast, elevated ROS levels exhibit superior antimicrobial efficacy at infected bone sites but may also induce collateral bone damage. To mitigate ROS-associated osteotoxicity following antibacterial treatment, integrated therapeutic strategies combining ROS-based antimicrobial approaches with osteogenic modalities have been developed, including growth factor delivery, osteoconductive scaffolds, and bioactive ion release systems. These combinatorial platforms enable precise antimicrobial action while simultaneously promoting bone defect repair and reconstruction of the pathological bone microenvironment.

Classification of ROS nanotechnology

Recent advances in nanotechnology, particularly in nanochemistry and nanofabrication, have enabled the development of a diverse range of ROS-generating nanomaterials with microenvironment-responsive and regulatory properties, which are increasingly applied across biomedical fields, including osteomyelitis therapy [71]. These nanomaterials produce distinct ROS upon stimulation by near-infrared (NIR), ultrasound (US), chemical reaction substrate, microwave energy, and related triggers, ultimately inducing irreversible bacterial damage and apoptosis. On the basis of their mechanisms of ROS generation and associated energy sources, ROS-based nanotechnologies are broadly categorized into PDT, SDT, CDT, and MWDT [72] (Table 1).

PDT employs photosensitizers that generate ROS upon irradiation with specific wavelengths of light, thereby directly inactivating pathogenic microorganisms. PDT exhibits broad applicability and a low propensity for inducing drug resistance. Within the hypoxic microenvironment characteristic of osteomyelitis, PDT predominantly generates ·O2- and ·OH through electron transfer-mediated Type I photochemical reactions, enhancing antimicrobial efficacy against drug-resistant bacteria.

Classification of ROS-based nanotechnologies.

| Method | Stimulus | Mechanism | Main ROS types | Advantage | Disadvantage | More suitable type of osteomyelitis | Prospects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDT | Light of specific wavelength | Type II photochemical reaction | ¹O₂ | Non-invasive, highly selective, can be applied locally | Limited tissue penetration depth, may cause phototoxicity, requires external light source | Acute/superficial osteomyelitis | New photosensitizers, wireless micro-LED light sources, and integrated diagnosis and treatment platforms |

| SDT | Ultrasound | US cavitation | OH and ¹O₂ | Deep tissue penetration, strong destructive power on biofilms | May cause tissue damage (such as thermal effects or mechanical damage), sonosensitizer delivery challenges | Chronic/biofilm-associated osteomyelitis | Multifunctional sonosensitizer, ultrasound-multimodal imaging guided therapy, portable device |

| CDT | Microenvironment endogenous substances | Fenton or Fenton-like reaction | ·OH | Does not rely on external energy, self-supplies H₂O₂/regulates the microenvironment | Reaction efficiency depends on the local environment (such as pH, H2O2 concentration) | Acute/chronic osteomyelitis | Intelligent responsive nanocatalytic materials, self-cycling CDT systems, catalytic immunotherapy |

| MWDT | Microwave | Thermal effect and non-thermal effect | ·OH, ¹O₂, or ·O₂⁻ | It has strong penetrating ability, rapid treatment, and is effective for deep and encapsulated biofilms | Thermal damage, complex and expensive equipment, difficult control, and the need for precise temperature monitoring | Chronic/deep/biofilm-associated osteomyelitis | Focus on microwave technology, microwave-responsive smart nanomaterials, and real-time ablation tools as surgical assistants |

SDT utilizes deep-penetrating ultrasound to excite sonosensitizers, leading to ROS production and mechanical effects. SDT demonstrates favorable penetration and targeting properties for deep-seated bone marrow infections while exerting minimal impact on surrounding healthy tissues. Furthermore, cavitation and shear forces generated during SDT disrupt bacterial biofilm architecture, thereby improving antibacterial efficiency. CDT exploits nanozyme-mediated Fenton or Fenton-like reactions within infection tissues to catalyze the conversion of endogenous hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) into highly reactive ·OH, enabling sustained ROS generation for antimicrobial activity without external energy input. In addition, certain catalytic systems incorporating calcium and magnesium release bioactive metal ions during the reaction process, synergistically promoting bone regeneration. MWDT relies on microwave sensitizers that generate both thermal effects and ROS under microwave irradiation, offering advantages of deep tissue penetration and highly efficient sterilization.

PDT for osteomyelitis treatment

Overview of PDT in osteomyelitis treatment

In the early twentieth century, von Tappeiner and Rabb first proposed the potential therapeutic potential of photosensitive synthetic dyes in combination with light and molecular oxygen and introduced the concept of "photodynamic action" [73]. Recently, PDT-based medical devices have been developed and approved for clinical application by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), underscoring the growing translational relevance of this modality [74,75].

PDT relies on the synergistic interaction among photosensitizers, tissue oxygen concentration, and an appropriate light source to induce microbial inactivation. Unlike conventional antimicrobial agents, PDT triggers cytotoxic reactions through light-induced excitation of photosensitizers, resulting in the generation of ROS that ultimately disrupt bacterial structures and functions. This mechanism represents a distinct class of anti-infective therapy with demonstrated efficacy against drug-resistant pathogens in both in vivo and in vitro settings. On this basis, photodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy (PACT) has been developed as a specialized application of PDT. PACT is founded on the selective location of non-toxic photosensitizers within pathogenic microorganisms, thereby minimizing off-target toxicity to surrounding tissues, followed by light activation at specific wavelength to generate highly cytotoxic ROS that inactivate pathogens [76]. PACT is therefore particularly suited for the treatment of microbial infections, including bacterial, fungal, viral, and parasitic diseases. In the context of osteomyelitis therapy, photosensitizers are delivered to the infected bone marrow cavity through systemic administration, such as intraperitoneal or intravenous injection, or by local injection. After a defined dark incubation period, the photosensitizer accumulates preferentially at the site of infection via blood circulation. Subsequent laser irradiation of the affected region induces localized ROS production, leading to efficient bacterial inactivation within the bone marrow cavity and therapeutic resolution of infection. Subsequent studies further confirmed the pronounced antibacterial efficacy of PACT in the bone marrow infections [77]. Notably, the successful application of PACT for the treatment of diabetic foot-associated osteomyelitis reported by Tardivo et al. demonstrated the safety and clinical effectiveness of this approach, offering a promising therapeutic option for refractory osteomyelitis [78].

Development and innovation of PDT for osteomyelitis treatment

Development of photosensitizers for osteomyelitis treatment

An ideal photosensitizer should exhibit high photodynamic efficiency, low intrinsic toxicity, adequate water solubility, and strong targeting capability [75]. Currently, photosensitizers used in PDT for osteomyelitis mainly include 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA) and phenothiazine derivatives. Conventional phenothiazine compounds, such as methylene blue and toluidine blue O (TBO), function as cationic photosensitizers and demonstrate favorable photodynamic antibacterial activity [75]. An in vitro study investigating the inhibitory effects of PDT on mature methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) biofilms in vitro revealed that TBO-mediated PDT induced pronounced morphological alterations, including biofilm shrinkage, fissuring, fragmentation, and thinning, accompanied by significant suppression of bacterial virulence [79].

Despite these advantages, clinical application of non-endogenous photosensitizers in antimicrobial therapy remains constrained by limitations related to incomplete characterization of metabolic pathways and potential cytotoxicity. In contrast, 5-ALA is rapidly metabolized into protoporphyrin IX by ALA dehydratase in vivo, resulting in reduced effective concentrations and heterogenous distribution, which in turn compromise PDT efficiency. Consequently, development of novel photosensitizers specifically tailored for osteomyelitis therapy represents an important task for advancing PDT-based treatment strategies. Yin et al. designed a new cationic photosensitizer, LD4, and evaluated its therapeutic performance in a rabbit tibial acute osteomyelitis model. In vivo results showed that LD4 exhibits good water solubility, low toxicity, targeting, strong targeting capacity, and pronounced antimicrobial activity in the treatment of infectious diseases [80]. Compared with conventional photosensitizers, LD4 exhibited broader photoinactivation efficacy as well as improved biocompatibility and physicochemical stability. Moreover, LD4-mediated PDT showed potential benefits in promoting bone healing and alleviating bone defects. Nevertheless, comprehensive assessment of potential adverse effects and long-term therapeutic outcomes of LD4 requires further validation through extended follow-up and clinical investigation.

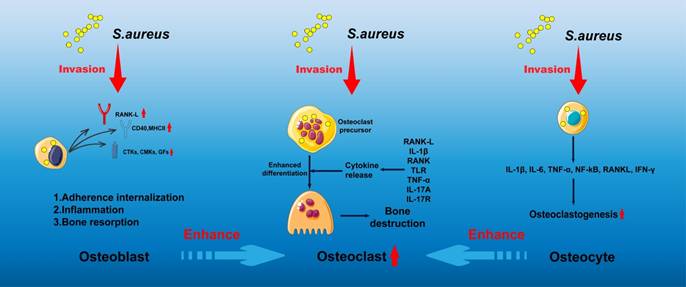

Schematic illustration of ZnO/Ag2S nanoparticles exhibiting combined photothermal and photodynamic effects for osteomyelitis treatment. Adapted with permission from Ref. [83]. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society.

Development of PDT nanomaterials for osteomyelitis therapy

At present, photosensitizer-mediated PDT, which has been successfully applied in the clinical treatment of tumors and superficial skin infections, has not yet been widely implemented for osteomyelitis management, primarily due to the mismatch between the deep anatomical location of osteomyelitis lesions and the limited issue penetration of conventional light sources. Enhancement of light penetration depth is therefore crucial for extending PDT applicability to osteomyelitis. The wavelength and energy density of the irradiation source exerts decisive influence on PDT efficacy, while tissue density and thickness further modulate penetration depth. NIR light exhibits superior tissue penetration compared with ultraviolet and visible wavelengths. Salehpour et al. reported that whereas the transmittance of a 660 nm laser through the scalp and skull was approximately 5.8%, an 810 nm laser achieved transmittance of (51.41 ± 2.12)% through the skull of male rats [81]. Notzli et al. further demonstrated that the maximum NIR penetration depth in cortical bone, cartilage, and trabecular bone reached 2.9 ± 0.2 mm, 3.5 ± 0.3 mm, and 3.5 ± 0.2 mm, respectively, confirming the feasibility of NIR-mediated PDT for osteomyelitis treatment [82]. Building upon these findings, multiple studies have explored NIR-activated PDT platforms for osteomyelitis therapy. For example, Wu et al. designed a biocompatible core-shell nanomaterial, ZnO/Ag2S nanoparticles, in which incorporation of Ag2S optimized the band-gap structure of ZnO, thereby improving photoelectric efficiency and ROS generation capacity. Density functional theory and ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy confirmed the stable photothermal and photodynamic properties of ZnO/Ag2S nanoparticles. These nanomaterials showed potent antibacterial activity upon NIR activation during the acute phase of infection and subsequently released Zn2+ ions during the chronic phase to promote bone regeneration [83] (Figure 3).

Combination of multimodal imaging and PDT in osteomyelitis therapy

In recent years, the combination of PDT with advanced imaging techniques, such as photoacoustic imaging (PAI) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), has enabled the development of dual-modal diagnostic and therapeutic platforms for osteomyelitis [84,85]. Compared with conventional optical imaging techniques, PAI offers the advantages of high optical contrast, superior US-based spatial resolution, and increased tissue penetration depth [86]. MRI, in contrast, provides excellent soft-tissue contrast and spatial resolution without the risks associated with ionizing radiation. Notably, PAI compensates for the relatively low spatial resolution of MRI, while MRI offsets the limited penetration depth of PAI. Consequently, the combined application of PAI and MRI during PDT treatment enables accurate delineation of infected regions and real-time guidance of antibacterial therapy, while overcoming the inherent limitations of single-modality imaging. PAI/MRI dual-modal imaging platforms facilitate comprehensive whole-body assessment alongside high-resolution visualization of local tissue architecture, thereby significantly improving early diagnosis and therapeutic precision in osteomyelitis management. For example, in addressing the clinical challenges of early detection and effective intervention, Lu and colleagues developed a multifunctional theranostic agent integrating indomyanine green-mediated PAI with Mn2+-enhanced MRI. This agent selectively accumulated at infection sites and enabled precise lesion identification under both MRI and US imaging, while simultaneously supporting PDT-based therapy. This work represents a successful example of integrated early diagnosis and photodynamic treatment for osteomyelitis [87].

In summary, the spatiotemporal controllability and broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity of PDT render this modality particularly well suited for osteomyelitis treatment. The noninvasive nature of PDT, together with its compatibility with advanced imaging techniques, provides a strong foundation for clinical translation in osteomyelitis treatment.

Challenges and prospects of PDT for osteomyelitis therapy

Despite significant progress, application of PDT in osteomyelitis particularly in deep-seated bone infections, remains constrained by limited light penetration, most notably the inability of conventional light sources to effectively traverse dense cortical bone. Although the introduction of NIR and development of advanced photosensitizers have partially alleviated these technical barriers, such strategies simultaneously raise concerns regarding undefined therapeutic dosages and potential biological safety risks. Furthermore, the oxygen dependence of conventional type II PDT restricts its therapeutic efficacy within the hypoxic microenvironment characteristic of chronic bone infection and biofilm-associated lesions. To address these challenges, several research teams have explored Type I photosensitizers and engineered oxygen-generating or oxygen-carrying nanomaterials; however, these approaches substantially increase the complexity of material design and introduce additional safety considerations. Additionally, comprehensive evaluation of the long-term biosafety, pharmacokinetics, and biodistribution of metal-based nanomaterials and organic photosensitizers remains essential prior to widespread clinical application. Therefore, future breakthroughs in PDT for osteomyelitis treatment hinge on the development of deeply penetrating and/or oxygen-independent photo therapeutic systems, such as NIR-II-responsive platforms and highly efficient self-oxygenating nanostructures, in parallel with the establishment of standardized light delivery protocols optimized for bone tissue and rigorous safety evaluation of next-generation photosensitizers.

In summary, PDT exerts antibacterial effects through light-activated photosensitizers that generate ROS, leading to microbial destruction. Nevertheless, reduced efficacy in deep infections, especially in osteomyelitis, remains a principal limitation. In this context, SDT, which offers superior tissue penetration, is anticipated to complement PDT and compensate for its intrinsic shortcomings, thereby playing an increasingly significant role in the treatment of deep bone infections.

SDT for osteomyelitis therapy

Overview of the application of SDT in osteomyelitis therapy

In 1989, Yumita et al. first reported the responsiveness of hematoporphyrin to US) irradiation and its associated antitumor effects, thereby introducing the therapeutic concept of SDT [88]. As a periodically oscillating mechanical wave, US possesses the capability to penetrate biological tissues to depths of up to approximately 10 cm, supporting the application of SDT in the treatment of deep-seated tumors, deep infections, and other pathological conditions in recent years [89].

The therapeutic mechanisms of SDT involve multiple synergistic processes, including mechanical injury caused by US cavitation, ROS generation mediated by sonosensitizer activation, regulation of intracellular signaling pathways leading to apoptosis, and enhancement of host body immune responses. Among these, US cavitation = and ROS production are considered the principal contributors to the potent antibacterial efficacy of SDT. Cavitation phenomena during SDT are generally classified into non-inertial and inertial cavitation [90]. Under conditions of localized high pressure and temperature, US cavitation within liquid environments produces mechanical forces, such as microstreaming, shock-wave generation, and sonoporation, that induce cellular damage and apoptosis. Sonoporation, in particular, results in the transient formation of reversible micropores on the cell membrane ranging from a few nanometers to several hundred nanometers in diameter, thereby increasing membrane permeability and facilitating improved delivery of therapeutic agents, genes, and bioactive molecules. Two main mechanisms have been proposed to explain ROS generation during SDT. In the first, collapse of cavitation bubbles during inertial cavitation triggers sonoluminescence, which stimulates the sonosensitizer and promotes reactions with molecular oxygen to generate ROS within tissues. In the second, localized high temperatures generated during US irradiation of liquid systems promote dissociation of oxygen-containing molecules, leading to ROS formation [91,92].

Compared with PDT, SDT offers superior tissue penetration and improved biosafety due to the mechanical nature of US energy. A variety of acoustic sensitizers, including precious metal-doped TiO2 (s.g., Pt, Pb, and Au), porphyrin-based single-atom catalysts, metal-organic framework nanoparticles, and piezoelectric nanomaterials such as MoS2 and BaTiO3, have exhibited effective SDT activity and the capacity to induce microbial apoptosis [93]. In recent years, the application of SDT in bacterial infection has expanded substantially, with particular promising outcomes reported in the treatment of osteomyelitis [94,95].

Development and innovation of SDT for osteomyelitis treatment

Development of acoustic sensitizers for osteomyelitis treatment

Over the past few decades, following the discovery of the acoustic activity of hematoporphyrin, an expanding range of acoustic sensitizers has been developed for antitumor and antibacterial applications. Advances in pharmaceutical nanotechnology have not only improved the stability and targeting efficiency of conventional porphyrin-based sensitizers but have also promoted the exploration of sound-responsive characteristics in various nanomaterials, thereby significantly enriching the application potential of sonosensitizing agents. Currently, acoustic sensitizers are mainly classified into organic sensitizers, inorganic sensitizers, and organic-inorganic hybrid sensitizers [96].

Organic acoustic sensitizers, representing the earliest class of agents applied in SDT, exhibit both photosensitive characteristics and sonodynamic activity under US irradiation. This category primarily consists of porphyrins, phthalocyanines, xanthene derivatives, phenothiazine compounds, fluoroquinolones antibiotics, natural products, and other organic small-molecule sonosensitizers [96]. Organic sensitizers are distinguished by high ROS production efficiency, tunable SDT performance, and favorable biodegradability. However, limitations such as poor water solubility, chemical instability, rapid systemic clearance, low bioavailability, and potential phototoxicity have restricted broader clinical application in antimicrobial therapy. In contrast, inorganic sensitizers, represented by TiO2, ZnO2, Bi2MoO6, BaTiO3, and MnWOx, offer superior physicochemical stability and allow flexible regulation of pore structure and surface functionalization, thereby providing notable advantages for in vivo targeted delivery [91]. Nonetheless, the limited biodegradability of inorganic sensitizers may result in cumulative systemic toxicity and long-term biosafety concerns, underscoring the importance and rigorous safety evaluation.

To address the respective limitations of organic and inorganic acoustic sensitizers, organic-inorganic hybrid acoustic sensitizers that integrate the advantages of both classes have been successfully developed and applied in recent years for exploratory clinical use in SDT. Among these, metal-organic framework (MOF)-based acoustic sensitizers have emerged as a major focus of current research [97]. MOF sonosensitizers consist of crystalline structures formed through coordination between metal ions or clusters and organic acoustic-sensitive ligands, featuring well-defined pores and cavities. The controllable cavity dimensions of MOFs enable incorporation of diverse functional components—such as quantum dots, nanoclusters, organic small molecules, or nanoparticles—either during or after synthesis, facilitating construction of multifunctional composite platforms that combine the beneficial properties of organic and inorganic acoustic nanomaterials. In addition, the large specific surface area, adjustable porosity, facile surface modification, and high drug-loading capacity of MOFs provide strong support for their application in antimicrobial SDT. The tunable pore architecture and intrinsic catalytic activity further positioned MOFs as highly promising next-generation sonosensitizers.

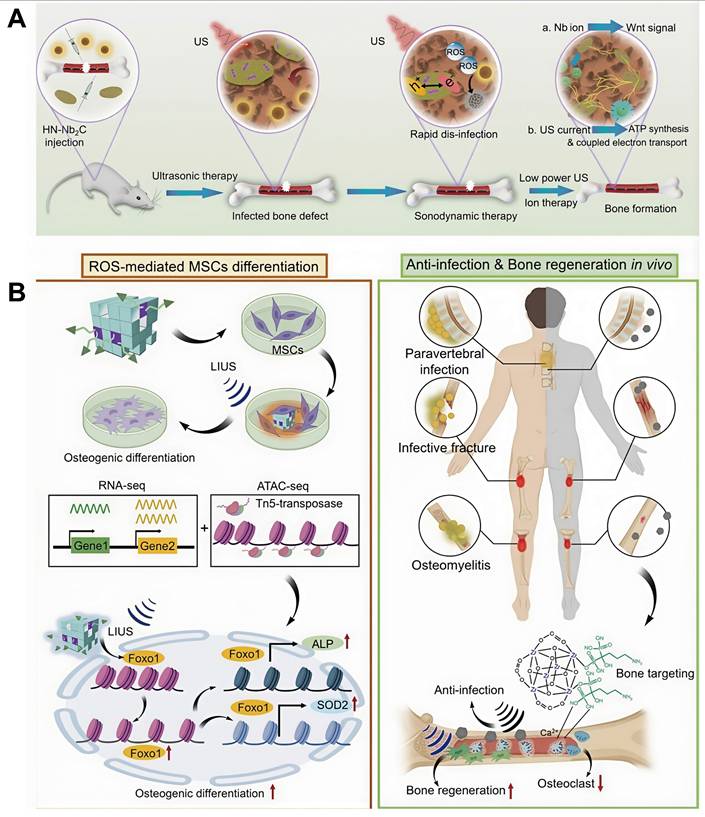

SDT nanomaterials for osteomyelitis therapy

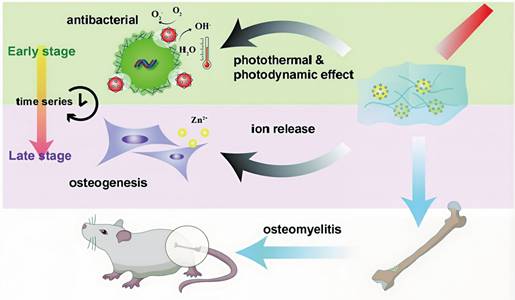

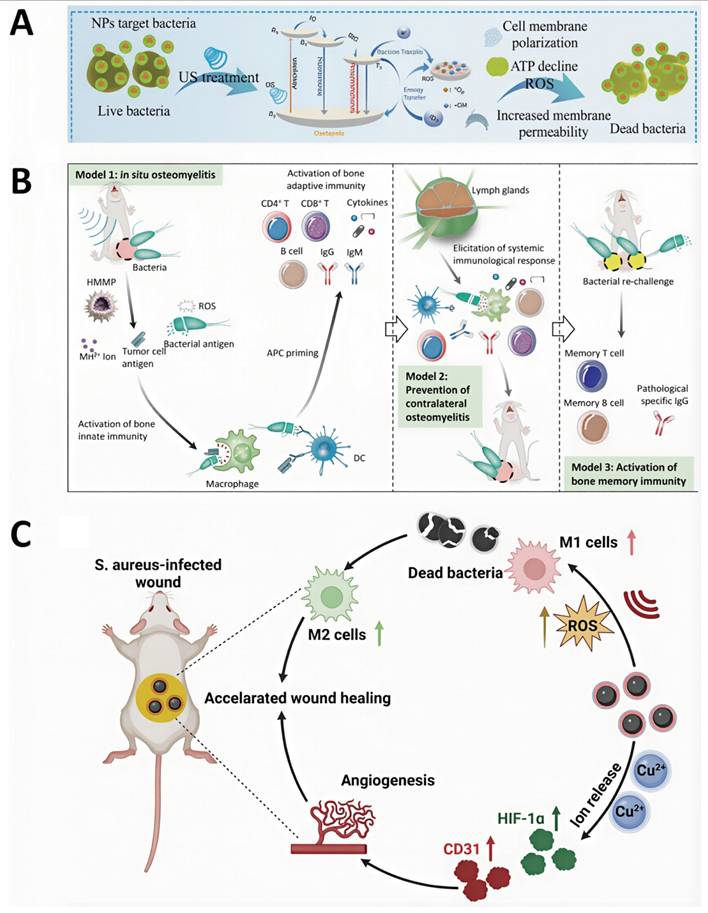

Targeted accumulation of acoustic sensitizers at osteomyelitis lesions is crucial for improving the therapeutic efficacy and bactericidal performance of SDT. For instance, Chen et al. developed cationic starch-modified curcumin nanoparticles (CS@Cur NPs). Owing to their positive surface charge, CS@Cur NPs effectively target bacteria with negatively charged cell membranes, resulting in capture rates of 34.7% for E. coli and 35.8% for S. aureus, respectively. Upon US irradiation, CS@Cur NPs produce substantial levels of ROS, inducing oxidative stress-mediated bacterial death through increased membrane permeability and disruption of ATP synthesis [98] (Figure 4A). In addition, biomimetic nanotechnology has also been used to further improve the targeting efficiency of SDT nanomaterials toward infected bone marrow. Lin et al. designed a biomimetic nanotherapeutic system, HMMP, constructed by combining hybrid membranes derived from macrophages and tumor cells with hollow MnOx nanoparticles encapsulating protoporphyrin IX (PpIX). This platform enabled efficient targeting of osteomyelitis infection sites and controlled ROS release, resulting in highly effective bactericidal activity within infected bone marrow [99] (Figure 4B).

The pathological microenvironment of osteomyelitis is characterized by acidic pH and high GSH levels, and adaptation of nanomaterials to these conditions is critical for improving SDT-mediated therapeutic outcomes. Stability of nanoparticles under acidic conditions represent a key requirement for effective SDT performance. Chen et al. investigated the influence of pH on the antibacterial effect of CS@Cur NPs and showed that these nanoparticles maintained stable and potent antimicrobial activity across a pH range of 3-7 [98] (Figure 4A). To counteract the inhibitory effects of high GSH levels on ROS-mediated antibacterial activity, Cheng et al. designed ultrasmall platinum-copper alloy nanoparticles (PtCu-PEG NPs) with strong GSH-depleting ability. Through enhanced ROS-based bactericidal mechanisms, PTKU-PEG NPs effectively suppressed deep S. aureus-induced osteomyelitis infection [100] (Figure 4C). These findings highlight the importance of microenvironment-responsive acoustic sensitizers in amplifying antibacterial efficacy.

Furthermore, to overcome bacterial antioxidant defenses such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), Yang et al. engineered calcium carbonate-gallium-protoporphyrin IX (CaCO3-Ga-PPIX) nanospheres (CaGaPP NSs) incorporating polyethylene glycol (PEG). the infected microenvironment, CaGaPP NSs selectively released Ga3+ ions that functioned as "Trojan horse" agents to disrupt bacterial metabolism and inhibit SOD activity, thereby further enhancing the antibacterial activity of SDT [101]. This work introduces a promising strategy that combines SDT nanomaterials with targeted suppression of bacterial systems for treatment of osteomyelitis.

In summary, SDT demonstrates significant antibacterial advantages through the combined effects of mechanical disruption mediated by US cavitation and ROS generation. Furthermore, owing to deep tissue penetration of US energy, SDT represents a particularly promising therapeutic strategy for osteomyelitis, especially for infections involving deep bone marrow lesions.

Challenges and prospects of SDT in osteomyelitis therapy

Although SDT strategy has gained increasing recognition for the treatment of osteomyelitis, several critical challenges remain to be addressed. Acoustic sensitizers represent a key determinant of SDT efficacy, yet current limitations related to complex preparation processes and unresolved in vivo biosafety concerns pose substantial barriers to clinical translation. Consequently, the rational design and development of multifunctional acoustic sensitizers remain central for future optimization of SDT-based osteomyelitis therapy. Emerging evidence indicates that MOF-based sonosensitizers integrated with hypoxia-adaptive SDT platforms offer promising solutions for refractory osteomyelitis. In particular, development of oxygen saturation-independent materials that leverage direct energy transfer or ROS catalytic amplification mechanisms has expanded the feasibility of SDT under hypoxic conditions. Future research should therefore prioritize systematic assessment of MOF biosafety and the development of degradable alternatives to support clinical translation. In addition, the existing US delivery systems lack the precision and operational flexibility required for consistent and convenient adjustment of acoustic parameters, limiting their suitability for clinical implementation. Development of next-generation US instruments with standardized and programmable acoustic parameters is thus another important direction for technological advancement. Moreover, the molecular mechanisms underlying SDT-induced apoptosis across different bacterial species remain incompletely understood and warrant further exploration.

In summary, SDT demonstrates considerable therapeutic promise for osteomyelitis owing to its superior tissue penetration ability. However, clinical efficacy is strongly influenced by the performance of US equipment and the stability of acoustic sensitizer delivery. In contrast, CDT, which does not rely on external energy input, enables sustained ROS generation and offers distinct advantages in the management of infections requiring continuous oxidative stress-mediated antimicrobial activity.

CDT for osteomyelitis treatment

Overview of CDT in osteomyelitis treatment

In 2016, Shi et al. formally introduced the concept of CDT [102]. Central to this therapeutic strategy are nanozymes, a class of nanoscale materials possessing intrinsic enzyme-like catalytic activity [103]. Nanozymes integrate the physicochemical properties of nanomaterials with the catalytic functions of natural enzymes, enabling efficient catalysis of biological substrate reactions under mild physiological conditions. Compared with natural enzymes, nanozymes typically exhibit greater thermal and chemical stability, enhanced environmental tolerance, lower production costs, and favorable scalability for mass production [104]. The discovery of nanozymes has challenged the traditional notion of inorganic materials as biologically inert and has revealed the inherent catalytic potential of nanomaterials, thereby expanding their utility across analytical chemistry, biosensing, environmental remediation, and biomedical applications. For example, cerium oxide (CeO2) and iron oxide (Fe3O4) nanoparticles with nanozyme activity have been widely explored for biosensing and therapeutic purposes [71]. Based on material composition, nanoenzymes are broadly classified into metal-based nanoenzymes, carbon-based nanoenzymes, metal-MOF nanoenzymes, and bio-derived nanoenzymes [104]. The core catalytic mechanisms underlying nanoenzyme-mediated CDT involve Fenton and Fenton-like reactions.

(A) Cationic starch-modified curcumin nanoparticles (CS@Cur NPs) for the treatment of MRSA-induced osteomyelitis, exhibiting anti-inflammatory activity and promotion of osteogenic differentiation. Adapted with permission from Ref. [98]. Copyright 2023, Wiley-VCH. (B) Schematic illustration of HMMP construction. Adapted with permission from Ref. [99]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. (C) Scheme representation of PtCu-PEG NP preparation for sonodynamic antibacterial therapy and tissue repair. Adapted with permission from Ref. [100]. Copyright 2023, Wiley-VCH.

During the CDT process, nanocatalytic systems exploit the excess H+ or H2O2 present within pathological lesions to drive Fenton or Fenton-like reactions. In iron-based nanomaterials, Fe2+ ions are released and catalyze the decomposition of endogenous H2O2 into highly reactive ·OH under acidic conditions according to the reaction

Fe2+ + H2O2 → Fe3+ + ·OH + OH-

In addition to iron, other redox-active metal ions, such as Cu+, Mn2+, and Mo6+, can also catalyze H2O2 conversion into ·OH. As a highly cytotoxic Type I ROS, ·OH induces cellular damage through phospholipid peroxidation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and DNA damage, while simultaneously activating caspase-3-dependent apoptotic pathways, ultimately leading to programmed death of both target cells and pathogenic microorganisms. A large number of metal-based nanocatalytic systems has therefore been developed to enhance the efficiency of Fenton and Fenton-like reactions, thereby improving CDT therapeutic efficiency [102,105].

Initially established as an effective strategy for cancer therapy, CDT depends on acidic microenvironments and elevated H₂O₂ concentrations to sustain efficient ROS generation. Owing to the similar pathological features of tumor tissues and infected bone marrow lesions—characterized by mild acidity, hypoxia, and excessive H2O2 —CDT has demonstrated considerable promise for osteomyelitis treatment. Within osteomyelitis lesions, Fenton and Fenton-like catalysts convert endogenous H₂O₂ into ROS, thus exerting potent antibacterial and immunomodulatory effects. Compared with PDT and SDT, CDT-based nanomaterials enable continuous ROS generate without relying on external energy sources, providing a more durable and operationally straightforward therapeutic approach for osteomyelitis management.

Development of CDT nanotechnology for osteomyelitis treatment

CDT nanotechnology for osteomyelitis treatment via H₂O₂ supply

Supply of H₂O₂ at sites of infection improves the therapeutic efficacy of CDT. Numerous studies have therefore leveraged the intrinsic accumulation of H₂O₂ within osteomyelitis lesions to optimize CDT-based treatment strategies. For example, Yu et al. developed two-dimensional TiC nanosheets loaded with CaO2, which showed robust CDT activity through self-supplied H₂O₂ generation, resulting in effective antimicrobial action and substantial therapeutic benefit in osteomyelitis models [106] (Figure 5A).

CDT nanotechnology for osteomyelitis treatment dependent on acidic microenvironment

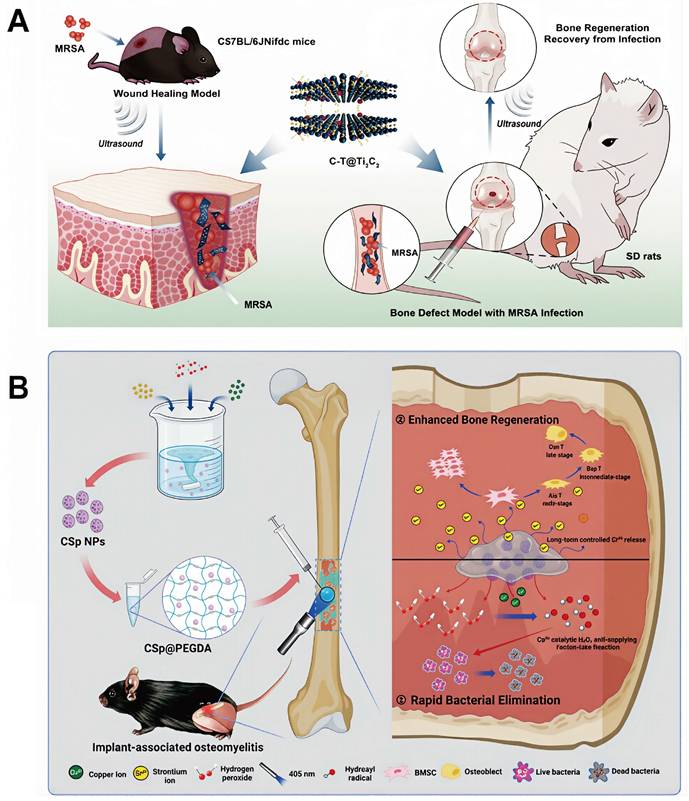

Efficient Fenton reactions require an acidic environment, typically with pH values ranging from 2 to 4, as elevated pH conditions inhibit nanomaterial decomposition and limit the release of catalytically active metal ions. The acidic microenvironment characteristic of osteomyelitis lesions therefore provides favorable conditions for high-efficiency CDT. For instance, Ge et al. constructed a multifunctional, pH-responsive drug delivery system by integrating zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8) with celecoxib (CEL@ZIF-8). This platform enabled intelligent release of both metal ions and therapeutic agents in response to the acidic conditions at the infection site, ultimately achieving effective osteomyelitis treatment [107]. Similarly, Guan et al. encapsulated copper-strontium peroxide nanoparticles (CSp) within PEG diacrylate (PEGDA) to generate CSp@PEGDA nanocomposites. These nanoparticles self-supplied H2O2 and released Cu²⁺ ions to initiate Fenton-like reactions, generating a large amount of ·OH for potent antibacterial activity. At the same time, the released Sr2+ ions enhanced osteogenic processes by promoting osteoblast proliferation, increasing alkaline phosphatase activity, facilitating extracellular matrix calcification, and upregulating gene expression related to bone formation [108] (Figure 5B).

Compared with tumor tissues, several intrinsic limitations restrict the application of CDT in osteomyelitis treatment, including relatively low endogenous H2O2 concentrations within bone infections and partial neutralization of the acidic microenvironmental by bone minerals and inflammatory responses. Accordingly, strategies involving autonomous H2O2 supplementation or glutathione depletion have proven effective in enhancing CDT efficiency. Furthermore, potential risks associated with metal accumulation and systemic toxicity arising from extensive use of transition metal catalysts, such as iron, copper, and manganese, warrant sustained investigation. Future development of CDT for osteomyelitis treatment should therefore focus on the design of highly efficient catalysts capable of operating under physiological or near-physiological conditions, the exploration of metal-free CDT nanozymes (e.g., carbon- and nitrogen-based structures), and the construction of intelligent nanoplatforms capable of dynamically sensing and modulating the pathological microenvironment. Integration of CDT strategies with osteogenic elements further represents a promising multifunctional therapeutic direction for osteomyelitis management.

(A) Schematic illustration of the synthesis and therapeutic performance of C-T@Ti3C2 nanosheets, including in vitro and in vivo antibacterial activity and bone defect repair in deep infections. Adapted with permission from Ref. [106]. Copyright 2023, Springer Nature. (B) Schematic illustration of the synthesis, antibacterial activity, and osteogenic performance of the CSp@PEGDA composite. Adapted with permission from Ref. [108]. Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH.

Challenges and prospects of CDT in osteomyelitis treatment

Development of CDT for osteomyelitis therapy relies heavily on effective exploitation and modulation of the pathological microenvironment characterized by elevated H2O2 levels, increased GSH, and acidic pH. Although CDT has emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy osteomyelitis, several biosafety challenges must be addressed prior to clinical translation. First, the complex and heterogeneous microenvironment of osteomyelitis lesions may introduce unpredictable safety risks during CDT treatment. Second, insufficient targeting accuracy and limited specificity of current CDT nanomaterials increase the potential for off-target effects and damage to normal tissues. Third, extensive use of metal-based components in CDT nanomaterials raised concerns regarding metal accumulation and systemic toxicity in vivo. Consequently, future optimization of CDT for osteomyelitis should prioritize realistic modeling of lesion microenvironments, refinement of nanoscale targeting strategies, and development of non-metallic CDT nanomaterials with improved biosafety profiles.

In summary, the main advantage of CDT lies in its independence from external energy input; however, its antibacterial efficiency remains highly sensitive to local microenvironmental conditions, and reliance on a single therapeutic modality increase the risk of treatment failure. In contrast, MWDT offers the ability to deliver precise microwave-induced hyperthermia while simultaneously generating ROS for effective sterilization. Through the synergistic action of thermal effects and ROS-mediated antibacterial mechanisms, MWDT provides a more comprehensive and efficient therapeutic approach for the management of chronic osteomyelitis, combining deep tissue penetration with rapid therapeutic responses.

MWDT for osteomyelitis treatment

Overview of MWDT in osteomyelitis treatment

Over the past decade, microwave activation has emerged as an increasingly attractive synergistic therapeutic modality due to its ability to induce both thermal effects and ROS, thereby enhancing antitumor and antimicrobial efficacy [109]. In 2017, Fu et al. formally introduced the concept of MWDT, which integrates the hyperthermic advantages of conventional microwave thermal therapy (MTT) with ROS-mediated cytotoxic mechanisms, providing a more comprehensive and effective clinical strategy [110]. ROS generation during MWDT is driven by both thermal and non-thermal effects associated with microwave irradiation. Microwave-induced heating accelerates ion migration and increases interionic collision frequency, leading to localized temperature rise and occurrence of redox reactions. Concurrently, microwave exposure alters cell membrane integrity and intracellular architecture, regulates the intracellular microenvironment, and further promotes ROS generation. Through these combined mechanisms, MWDT enables localized ROS generation at targeted tissue sites by simultaneously promoting redox reactions and interfering with intracellular signaling pathways [111,112].

In recent years, application of MWDT for the treatment of bacterial infections has expanded, with particularly encouraging outcomes reported in the treatment of osteomyelitis [113-119]. Microwave irradiation offers substantial tissue penetration depth and effectively heats tissues with low electrical conductivity, high impedance, and low thermal conductivity, such as bone [120]. Moreover, high microwave-to-thermal conversion efficiency enables rapid achievement of bactericidal temperatures exceeding 100 °C, thereby significantly shortening treatment duration [120]. In parallel, extensive evidence confirms that microwave exposure promotes ROS generation [121]. Collectively, these features establish microwave-responsive nanomaterials with unique physicochemical properties as promising platforms for advanced antimicrobial therapy of osteomyelitis.

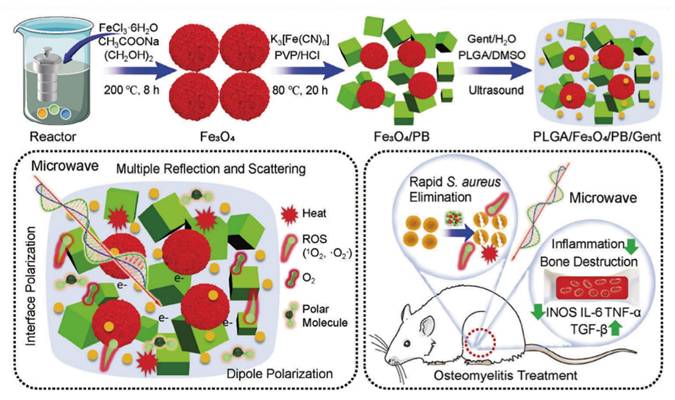

Development of MWDT for osteomyelitis treatment

Design of MWDT nanomaterials

Microwave-absorbing materials convert microwave energy into thermal or other forms of energy through absorption and attenuation processes. The main mechanisms underlying microwave absorption include electromagnetic loss, magnetic loss, dielectric loss, and multiple reflection, which may operate individually or synergistically to confer efficient absorption performance [122,123]. At present, microwave-responsive nanomaterials encompass both materials with intrinsic wave-absorbing properties and materials exhibiting microwave dynamic activity [124-126]. Among these, nanomaterials with microwave dynamic properties are most frequently employed in the design and development of MWDT nanomaterials for osteomyelitis treatment. Nanomaterials with microwave dynamic properties usually possess H2O2-like enzymatic behavior or intrinsic microwave catalytic activity. For example, Mn-Zr-doped MOFs have been shown to act as H2O2-mimicking enzymes, catalyzing H2O2 decomposition into ·OH under microwave irradiation [164]. This phenomenon is attributed to microwave-induced acceleration of electron transfer within the material, facilitating excitation of H2O2 molecules from the ground state and ultimately triggering rapid ·OH generation. In contrast, nanomaterials exhibiting microwave catalytic activity, such as Ga/In alloy nanostructures, are capable of directly producing ROS under microwave irradiation. This phenomenon arises from the formation of high-temperature “hot spots” on material surfaces created by localized resonant coupling of microwave energy, where electron transfer from Ga to H2O or O2 is promoted, thereby enhancing production of ·OH and superoxide anion radicals ·O2- [109].

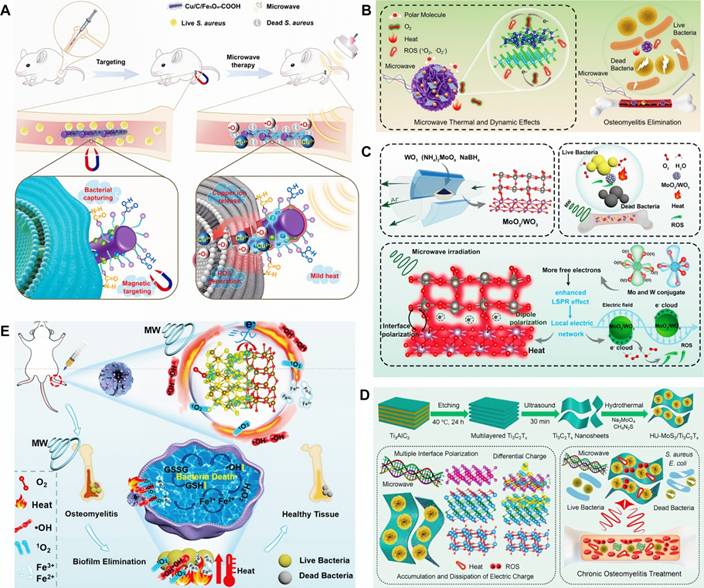

Application of MWDT nanomaterials in osteomyelitis treatment

MWDT nanomaterials used in osteomyelitis therapy are mainly categorized into magnetic loss materials and dielectric loss materials. Magnetic loss materials are typically represented by polymer composites filled with magnetic components such as ferrites or carbonyl iron powder. Notably, Fe3O4 nanoparticles have already received approval from the U.S. FDA for certain medical applications. Ren et al. developed an effective Cu/C/Fe3O4-COOH nanocomposite for osteomyelitis therapy, in which Fe3O4 nanoparticles with strong magnetic loss characteristics improved microwave absorption through optimized impedance matching of the dielectric matrix. Targeting of bacterial cells was achieved via interactions between surface -COOH groups on the nanocomposite and -NH2 groups on the bacterial walls. Under microwave irradiation, Cu/C/Fe3O4-COOH generated both thermal energy and ROS, resulting in disruption of bacterial membrane integrity and permeability. Antibacterial inhibition against S. aureus reached 99.99 ± 0.009% [127] (Figure 6A). Dielectric loss materials depend on tunable dielectric properties of carbonaceous or metallic fillers, which can be regulated through control of material thickness, depth, and filler composition. Jin et al. developed a microwave-responsive nanocomposite composed of MoS2/FeS and emodin (Rhein). Under microwave exposure, MoS2 promoted dipole polarization and ion conduction, resulting in molecular friction and dielectric loss, ultimately generating both thermal energy and ROS. The combined effects of singlet oxygen (1O2), superoxide anion (•O2-) and thermal energy achieved nearly 100% antibacterial efficacy against S. aureus and E. coli [128] (Figure 6B). Furthermore, binary metal oxides exhibit superior electrical conductivity and increased oxygen vacancy density compared with single metal oxides, thereby enhancing electron migration and providing abundant dipolar polarization sites. Based on the principle that interfacial polarization in binary metal oxides improves microwave absorption through enhanced conductivity loss, Zhu et al. designed a microwave-responsive MoO2/WO3 heterojunction for treatment of MRSA-induced osteomyelitis. Owing to tits high electrical conductivity, favorable dielectric loss characteristics, and excellent thermal stability, MoO2/WO3 achieved potent bactericidal activity and effective osteomyelitis treatment through the synergistic action of thermal effects and ROS generation. Inhibition rates against S. aureus and MRSA reached 99.27 ± 0.02% and 99.23 ± 0.43%, respectively [129] (Figure 6C).

In recent years, composite microwave-absorbing materials that integrate both magnetic and dielectric properties have been designed for osteomyelitis treatment to achieve synergistic antibacterial effects. For example, Jin et al. developed a MoS2/Fe3O4 composite to demonstrated effective therapeutic outcomes in osteomyelitis. The synergistic interaction between MoS2 and magnetic Fe3O4 facilitates multiple magnetic loss mechanisms, enhanced dielectric reflection, and interfacial polarization, thus conferring excellent microwave-induced thermal effects and efficient generation of 1O2 and ·O2-, which are essential for successful treatment of S. aureus-infected tibial osteomyelitis [130] (Figure 6D). Similarly, Liao et al. fabricated a Fe2O3/Fe3S4 composite material with strong microwave absorption capacity, enabling effective conversion of electromagnetic energy into heat. Upon microwave irradiation, differential charge accumulation and consumption at the Fe2O3/Fe3S4 interface enhance free electron release and subsequent binding with oxygen adsorbed on the composite surface, ultimately triggering a rapid burst of ROS. The combined magnetic loss and dielectric loss mechanisms promote simultaneous ROS generation and localized hyperthermia, leading to increased bacterial membrane permeability, oxidative stress induction, and eventual bacterial apoptosis. Antibacterial efficiencies of Fe2O3/Fe3S4 reached 99.87% against S. aureus and 99.59% MRSA [131] (Figure 6E).

By leveraging the deep tissue penetration properties of microwave radiation, MWDT enables simultaneous induction of localized hyperthermia and ROS-mediated antibacterial effects, generating a synergistic therapeutic outcome that substantially exceeds the efficacy of either modality alone. The high energy of microwave irradiation overcomes the penetration limitations inherent to phototherapy and demonstrates substantial potential for treating deep-seated and refractory bone infections.

Challenges and prospects of MWDT in osteomyelitis treatment

Several key challenges currently limit the clinical translation of MWDT for osteomyelitis therapy. First, existing MWDT platforms lack precise targeting capability toward infected lesions. Second, currently available microwave sensitizers often exhibit insufficient microwave responsiveness and suboptimal thermal conversion efficiency, thereby limiting therapeutic effectiveness in osteomyelitis management. Third, inadequate control of heat distribution during microwave irradiation introduces the risk of collateral thermal injury to surrounding healthy tissues or vital organs. Consequently, incorporation of advanced imaging probes and targeting moieties is expected to facilitate the development of multifunctional micro-and nanomaterials, enabling more precise, efficient, and safe MWDT techniques for osteomyelitis therapy.

In summary, the four major ROS-based therapeutic strategies discussed above—PDT, SDT, CDT, and MWDT—each exhibit unique advantages while also presenting unavoidable limitations. Future osteomyelitis treatment paradigms are therefore likely to evolve toward multimodal combination therapies to overcome the shortcomings associated with single-modality interventions. Integration of PDT, SDT, CDT, and MWDT provides expanded opportunities for personalized osteomyelitis treatment, with particular promise for addressing chronic, deep-seated, and refractory infections. Continues technological innovation and development of advanced therapeutic modalities are expected to further refine osteomyelitis treatment strategies, ultimately improving clinical outcomes and overall patient quality of life.

Combination of different ROS nanotechnologies for osteomyelitis treatment

Although ROS-based nanotechnologies, including PDT, SDT, CDT, and MWDT, have shown substantial therapeutic potential and promising application prospects in osteomyelitis management, single-modality dynamic treatment strategies remain insufficient to achieve rapid and comprehensive control of complex microbial infections. Consequently, contemporary ROS-based therapeutic approaches for osteomyelitis have gradually shifted from monotherapy toward multimodal combination strategies to enhance infection eradication and promote effective wound healing. Integration of complementary dynamic treatment strategies enables mutual compensation for the inherent limitations of individual approaches and facilitates synergistic interactions among different ROS-generating mechanisms and auxiliary therapeutic components, thereby producing a therapeutic outcome that exceeds the efficacy of any single strategy alone. This section summarizes current combinatorial strategies involving multiple ROS-based nanotechnologies, with the aim of elucidating their synergistic mechanisms and evaluating the potential of integrated therapeutic platforms in addressing the multifaceted challenges posed by osteomyelitis-associated infections.

(A) Schematic diagram of Cu/C/Fe3O4-COOH for treatment of S. aureus-infected osteomyelitis. Adapted with permission from Ref. [127]. Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH. (B) Microwave-assisted therapeutic strategy for treating S. aureus-infected osteomyelitis using a microwave-responsive MoS2/FeS nanocomposite modified with rhein. Adapted with permission from Ref. [128]. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH. (C) Schematic representation of MoO2/WO3 synthesis, microwave-mediated osteomyelitis treatment, and the combined mechanisms of microwave thermal and catalytic effects. Adapted with permission from Ref. [129]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. (D) Microwave-based treatment strategy for COM with S. aureus infection using MoS₂/Ti₃C₂Tₓ heterojunctions generated via hydrothermal treatment, featuring oxygen vacancy-rich TiO2-x interfaces. Adapted with permission from Ref. [130]. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH. (E) Schematic illustration of the preparation of Fe2O3/Fe3S4 composite materials. Adapted with permission from Ref. [131]. Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH.

Combination of PDT and SDT for osteomyelitis treatment

SDT offers superior tissue penetration compared with PDT, whereas PDT benefits from photosensitizers that exhibit hinger intrinsic ROS generation efficiency [132,133]. Consequently, combination of PDT and SDT enables simultaneous optimization of tissue penetration and ROS generation, making this combination particularly suitable for the treatment of osteomyelitis with deep tissue involvement. Ding et al. synthesized barium titanate nanotubes (BNTs) through a combined anodic oxidation and hydrothermal process, achieving efficient ROS generation and potent antibacterial activity under both US and NIR irradiation via synergistic piezoelectric and pyroelectric effects. The coordinated action of PDT and SDT further enhanced charge transfer and electron-hole pair separation, thereby amplifying the coupled pyroelectric-piezoelectric catalytic effect and markedly increasing ROS output. The resulting ROS burst induces extensive structural and functional damage to bacterial DNA and proteins, eventually leading to irreversible bacterial cell death. In vivo experiments showed that the antibacterial efficacy of BNTs reached up to 99% [134].

Combination of SDT and CDT for osteomyelitis treatment

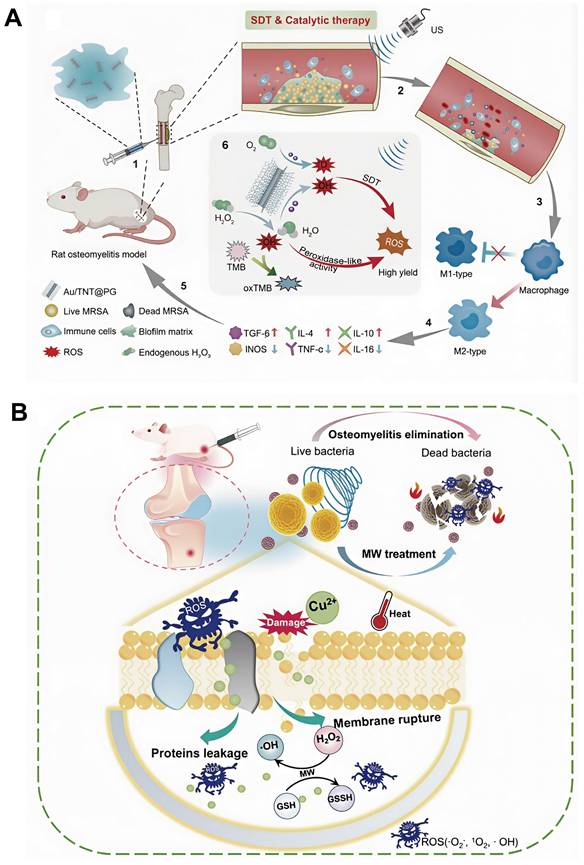

Previous studies have reported that localized turbulence generated by US shock waves can significantly improve the efficiency of Fenton reactions. The observation has provided a strong foundation for the development of synergistic strategies integrating SDT with CDT to achieve antimicrobial outcomes. For example, Cheng et al., conjugated a guanidin-rich polymer (PG) onto gold-doped titanate nanotubes (Au/TNTs) capable of absorbing US, thereby constructing multifunctional nanostructures (Au/TNT@PG) that simultaneously exhibit sonodynamic properties and peroxidase-like catalytic activity. US absorption by Au/TNT@PG markedly enhanced CDT efficiency and ·OH generation. In addition, the biofilm-penetrating characteristics of PG facilitated efficient biofilm disruption and induction of bacterial apoptosis, resulting in superior antibacterial efficacy [135] (Figure 7A).

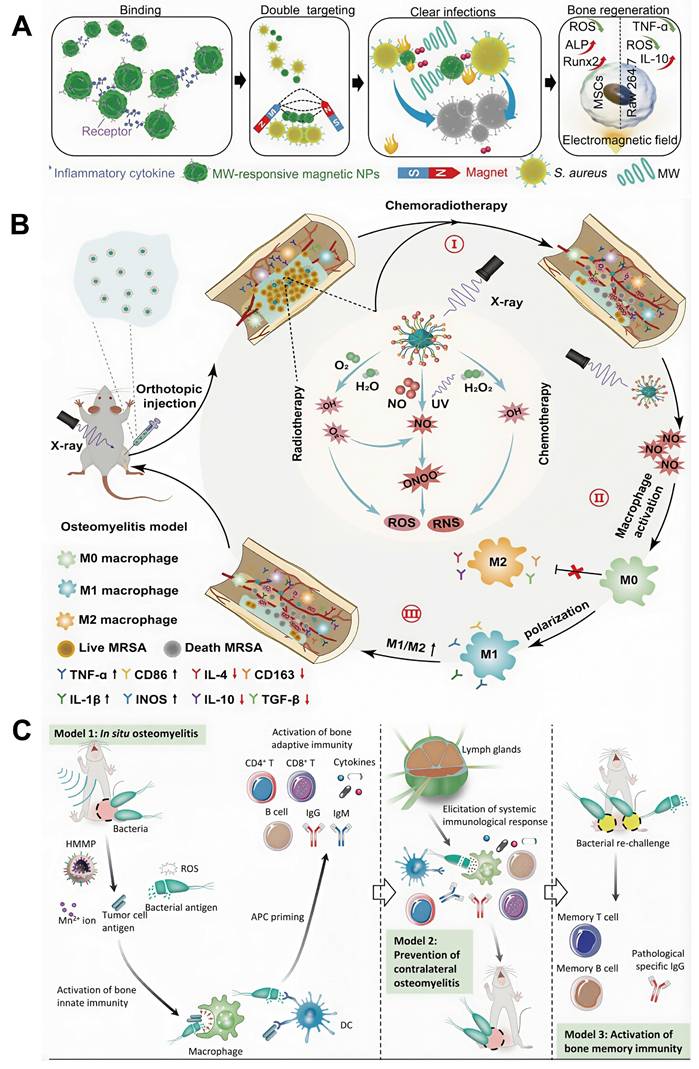

Combination of MWDT and CDT for osteomyelitis treatment