13.3

Impact Factor

Theranostics 2026; 16(5):2310-2323. doi:10.7150/thno.122123 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Clearance of amyloid plaque via focused ultrasonication in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease

1. Department of Pharmacy and Yonsei Institute of Pharmaceutical Science, College of Pharmacy, Yonsei University, Incheon, Republic of Korea.

2. Bionics Research Center, Biomedical Research Division, Korea Institute of Science and Technology, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

3. Happy mind Clinic, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

4. Department of Neurology, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul, Republic of Korea.

5. Department of Neurology, Dongtan Sacred Heart Hospital, Hallym University College of Medicine, Hwaseong-si, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea.

*These authors contributed equally to this work.

Received 2025-7-21; Accepted 2025-11-18; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

Background: The success of anti-amyloid-β (Aβ) monoclonal antibodies in recent clinical trials validates the promising approach of clearing amyloid-β in Alzheimer's therapy. Building on these successes, focused ultrasound (FUS), a non-invasive therapeutic modality that delivers acoustic energy to targeted brain regions with high precision, has emerged as a potential technique to modulate Aβ pathology, either in combination with drugs or as a standalone treatment. This study focused on the standalone potential of FUS to reduce Aβ plaques without accompanying drugs.

Methods: Synthetic Aβ42 aggregates were prepared and exposed to FUS. The changes in fibril and oligomer levels were analyzed using Thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence, gel electrophoresis combined with photo-induced cross-linking of unmodified protein (PICUP) chemistry, transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and immunoblotting. The effect of FUS on Aβ42-induced cytotoxicity was evaluated in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells. FUS-mediated dissociation of Aβ plaques was performed by ex vivo and in vivo methods on the 5XFAD mouse model. In the ex vivo experiment, FUS was applied to brain slices, specifically targeting the hippocampal region. In the in vivo experiment, the left hippocampus of awake animals was sonicated in a transcranial manner ten times over two weeks using a miniature ultrasound transducer affixed to the skull. For both ex vivo and in vivo experiments, immunohistochemistry was performed on brain sections for measuring Aβ plaques after sonication. Blood was collected from animals before and after in vivo stimulation for plasma analysis.

Results: In vitro, FUS treatment reduced the β-sheet structure of synthetic Aβ42 aggregates by up to 55.28% in the ThT assay, and fibrillar Aβ42 levels by up to 62.27% in the gel electrophoresis, as further confirmed by TEM imaging, which showed disrupted fibrillar structures. The level of oligomeric Aβ42 was also reduced by up to 65.02% following FUS exposure. SH-SY5Y cells treated with FUS-treated Aβ42 aggregates exhibited improved viability from 81.56% to 90.48%, showing a tendency of attenuated Aβ42-induced cytotoxicity by FUS. Ex vivo FUS stimulation significantly reduced the number of Aβ plaques in the hippocampal region compared to untreated brain slices. In vivo transcranial FUS reduced both the number and size of plaques in the FUS-treated hippocampal and thalamic region compared to the contralateral side. Plasma analysis with Aβ42 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay revealed a 65.91% increase in Aβ levels following FUS treatment compared to pre-treatment levels, suggesting that Aβ plaques dissociated by FUS were released into the bloodstream.

Conclusions: FUS exposure effectively reduced amyloid plaques in both ex vivo and in vivo models by disrupting fibrillar and oligomeric Aβ, demonstrating its potential as a non-invasive strategy for Aβ clearance.

Keywords: amyloid-β, focused ultrasound, non-invasive brain stimulation, 5XFAD transgenic mouse

Background

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cognitive decline, memory impairment, and functional deterioration of the brain [1, 2]. A defining pathological hallmark of AD is the accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides in the brain, which aggregate to form insoluble plaques that disrupt neuronal networks and ultimately lead to cell death [3]. Thus, Aβ clearance has emerged as a pivotal therapeutic strategy in AD for modifying disease progression [4]. Recently, monoclonal antibody therapies such as lecanemab and donanemab received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for their ability to reduce amyloid burden in the brain [5-7]. Despite their promise, these therapies are associated with serious adverse effects, including cerebral edema and microhemorrhages, underscoring the urgent need for safer, effective alternatives to mitigate Aβ pathology in AD [8, 9].

Focused ultrasound (FUS) is a non-invasive therapeutic technique that employs precisely targeted acoustic energy to treat specific brain regions [10, 11]. Recently developed AD treatment techniques aim to modulate cholinergic pathways, drug delivery via cerebral spinal fluid (CSF), and temporal change of blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability [12, 13]. Initial studies in AD primarily investigated the use of FUS, typically in combination with intravenously administered microbubbles, to temporarily open the BBB, thereby facilitating enhanced delivery of anti-amyloid drugs to the brain [14, 15]. Subsequent research revealed that FUS-induced BBB opening alone, without using additional anti-amyloid drugs, can also reduce Aβ fibrils and recover cognitive function in both animal models and AD patients [16, 17]. BBB opening has been shown to improve lymphatic clearance of Aβ in 5XFAD mouse model [18]. Furthermore, repeated bilateral sonication using FUS reduced both Aβ plaques and tau protein in the 3xTg-AD mouse model, and decreased amyloid levels in human AD patients [19]. More recent studies have taken this a step further, demonstrating that FUS alone, without microbubble or BBB opening, can improve drug delivery by disrupting non-covalent interactions between plasma proteins and therapeutic agents, thereby increasing their bioavailability [20]. Notably, these studies also showed that FUS can directly disrupt Aβ fibrils, suggesting its potential as a promising standalone strategy for targeting and dissociating amyloid plaques.

Building upon aforementioned emerging evidences, our study explores the direct application of FUS without BBB opening or pharmacological co-intervention, focusing solely on its capability to dissociate Aβ aggregates. We investigated FUS-induced Aβ dissociation through in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo experiments using synthetic Aβ42 peptides and 5XFAD transgenic mice. In the in vitro experiments, synthetic Aβ42 aggregates were exposed to FUS to confirm the physical disruption of Aβ aggregates by FUS. In the ex vivo experiments, brain tissue containing plaques was collected and treated with FUS to evaluate its potential for clearing amyloid plaques. In the in vivo experiments, FUS was applied to the hippocampal region over two weeks to assess its feasibility as a therapeutic intervention. Both ex vivo and in vivo approaches resulted in a significant reduction in plaque burden, and an increase in plasma Aβ42 levels was observed in vivo, indicating plaque clearance. These findings highlight the therapeutic promise of FUS in targeting amyloid pathology.

Methods

FUS stimulation setup

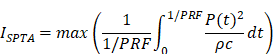

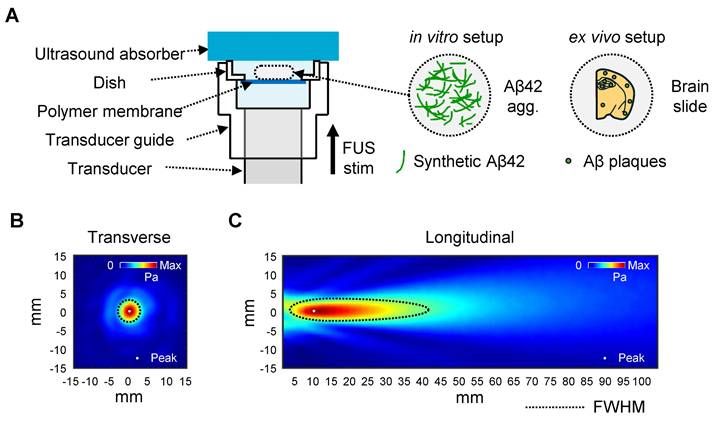

The sonication setup consisted of a function generator (33510B, Keysight Technologies, USA) and a linear radio frequency (RF) power amplifier (240L, Electronics and Innovations, USA). In brain slice experiments, a single-element focused ultrasound with a 500 kHz center frequency (GPS500-D19-P38, The Ultran Group, USA) was used. For in vivo transcranial focused ultrasound (tFUS) stimulation in awake animals, an in-house built single-element miniature transducer with a 450 kHz center frequency was used. The intensity maps of both transducers were measured in degassed, deionized water using a needle-type hydrophone (HNR-0500, ONDA Corp., USA). The full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) dimensions of the acoustic intensity field for the 500 kHz transducer were approximately 7 mm in the lateral direction and 50 mm in the axial direction. The FWHM of the acoustic intensity field of the 450 kHz transducer was approximately 1.5 mm in the lateral direction and 4 mm in the axial direction.

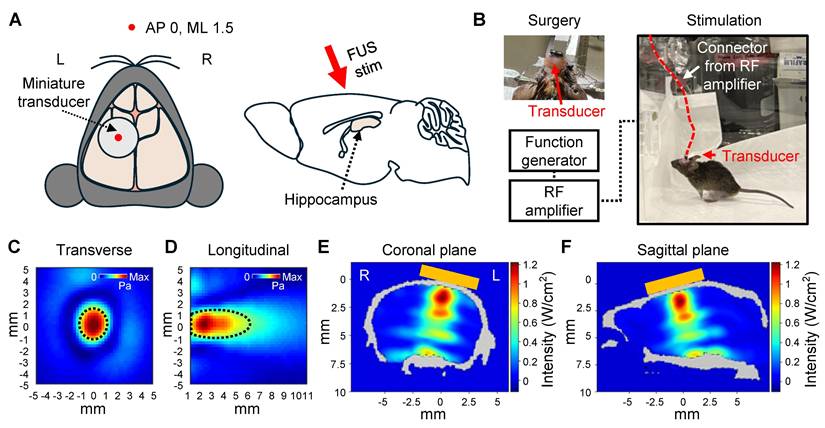

In the brain slice stimulation, the protocol was as follows: 100 ms pulse duration (PD), 10% duty cycle (DC), 1 Hz pulse-repetition frequency (PRF), 1 s pulse repetition interval (PRI), 5 W/cm2 spatial-peak pulse-average intensity (ISPPA), and 0.5 W/cm2 spatial-peak temporal-average intensity (ISPTA) for 30-minute pulse train duration (PTD). In the in vivo awake tFUS stimulation, the protocol was as follows: 100 ms PD, 10% DC, 1 Hz PRF, 1 s PRI, 1.75 W/cm2 ISPPA and 0.175 W/cm2 ISPTA for 30-minute PTD. The parameters are reported following the ITRUSST consensus for standardized reporting of transcranial ultrasound stimulation [21]. ISPPA and ISPTA were calculated as follows [22]:

* P, pressure; ρ, density of the propagating medium; c, speed of sound in the propagating medium; PRF, pulse repetition frequency; PD, pulse duration.

Acoustic simulation

Acoustic simulations were conducted using the k-Wave MATLAB toolbox to estimate the distribution of acoustic intensity within the brain [23]. A 450 kHz transducer for awake tFUS stimulation with specifications identical to those outlined in the FUS stimulation setup was employed, featuring a width of 13 mm and a radius of curvature of 5.5 mm. The simulation domain was defined as 150 × 150 × 130, with a grid resolution of 20 points per wavelength (equivalent to 0.16 mm spacing). Ultrasound waves were applied for 100 μs to allow sufficient time for the focal point to fully form, and the Courant-Friedrichs-Lewy number was set to 0.05.

To model the geometry of the mouse skull, a statistical parametric mapping-based template was utilized [24]. Regions with voxel intensities exceeding 1500 Hounsfield units were segmented as skull, excluding the diploe structure from the model. Both the skull and transducer were assumed to be submerged in water for the simulation [25]. The acoustic properties defined for the simulation included water (speed of sound: 1482 m/s, density: 1000 kg/m³) and skull tissue (speed of sound: 2442 m/s, density: 1969 kg/m³) [26]. Skull attenuation coefficients were not factored into the calculations.

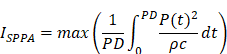

Figure 4E and 4F show 2D cross-sectional views of the regions within the brain exhibiting the highest acoustic intensity. The simulation determined that the ISPPA reached 1.22 W/cm², representing a reduction of approximately 30% compared to the free water intensity of 1.75 W/cm².

In vitro and ex vivo experimental setup. (A) Schematic diagram of the FUS-induced synthetic Aβ42 or brain slice stimulation setup. (B-C) Beam profile of the FUS stimulation along the transverse (B) and longitudinal (C) planes of the focus. The dotted line indicates the FWHM, and the white dot indicates the location of the peak pressure. stim, stimulation; agg., aggregates.

In vitro and ex vivo FUS setup

A 35 mm imaging dish with a polymer coverslip bottom (μ-dish, 35 mm, low, ibidi GmbH, Germany) was used for FUS stimulation. A customized ultrasound guide was attached to the front of the transducer to mount the imaging dish. The guide was designed to secure the dish precisely at the transducer's focal point, ensuring accurate ultrasound stimulation delivered to the sample placed on the dish. The guide, combined with the transducer, supports the dish from below, allowing the ultrasound beam to be delivered vertically upward through the tissue.

In vitro FUS experiment

Aβ42 peptides were synthesized using the dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)-incorporated fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl chloride (Fmoc) solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) as previously reported [27]. Aβ42 peptides were dissolved in DMSO to prepare a 1 mM stock solution, which was stored at -80 °C until use. The Aβ42 stock was thawed and immediately diluted in a sodium phosphate buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate buffer with 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) to prepare a 25 μM Aβ42 solution. Aβ42 solutions were incubated for 2 days with agitation (400 rpm) at 37 ℃ to induce aggregation. Aβ42 aggregates were placed on an ibidi dish (80136) and exposed to FUS for 30 min. Non-incubated Aβ42 solution and non-FUS-treated Aβ42 aggregates were used as controls.

Thioflavin T (ThT) assay

A 5 μM ThT (T3516, Sigma, USA) solution was prepared in 50 mM glycine buffer (pH 8.5) and protected from light until use. Aliquots of 25 μL of each sample were loaded into a 96-well half-area black flat-bottom microplate (3694, Corning, USA) and mixed with 75 μL of ThT solution. After incubation for 5 min at room temperature, fluorescence intensity was measured at an excitation/emission wavelength of 450/480 nm using an Infinite® 200 PRO microplate reader (TECAN, Switzerland). All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Immunoblot assay

For western blot with photo-induced cross-linking of unmodified protein (PICUP) chemistry, 1 mM Tris(2,2-bipyridyl)dichlororuthenium(II) hexahydrate (RuBpy; 544981, Sigma, USA) and 20 mM ammonium persulfate (APS; 431532, Sigma, USA) were prepared in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5). Each 10 μL of the Aβ sample was mixed with 1 μL of each RuBpy and APS solution. The mixture was irradiated with visible light three times for 1 s, with 1-s intervals between irradiations. After irradiation, 3 μL of 5x sample buffer containing 10% (w/v) dithiothreitol (DTT) was added. Each 15 μL of sample was loaded onto a 4-20% gradient polyacrylamide gel (4561095, BIO-RAD, USA) and electrophoresed at 150 V. Proteins were transferred onto a PVDF membrane (1620177, BIO-RAD, USA) at 100 V for 30 min, and the membrane was blocked with 5% (w/v) skim milk in tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was probed with 6E10 anti-Aβ antibody (SIG-39320, BioLegend, USA; 1:10,000), followed by a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) secondary antibody (115-035-003, Jackson ImmunoResearch, UK; 1:50,000). For the oligomer dot blot assay, Aβ42 samples were spotted twice (2 μL each) onto a nitrocellulose membrane, with the second spot applied after the first had completely dried. The membrane was dried for 30 min, blocked with 5% (w/v) skim milk in TBST for 1 h at room temperature, and probed with anti-amyloid oligomer A11 antibody (AHB0052, Invitrogen, USA; 1:1500) followed by HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (111-035-003, Jackson ImmunoResearch, UK; 1:15,000). Signals were developed using SuperSignal™ West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate (34580, ThermoFisher, USA) and visualized with the FUSION Solo S software program.

Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM)

Carbon-coated copper grids (CF200-CU, YMS, Korea) were glow-discharged using a PELCO easiGlow (Ted Pella, USA). Aβ42 samples were applied to each grid and incubated for 1 min. Excess solution was removed with filter paper, and the grids were negatively stained with 5 μL of 2% (w/v) uranyl acetate for 10 s. After complete drying, the samples were imaged using a Talos L120C (ThermoFisher, USA).

Cell viability assay

For the viability assay, Aβ42 solutions were prepared by diluting 5 mM Aβ42 DMSO stock to 25 μM with sodium phosphate buffer. The Aβ42 samples were incubated for 2 days at 37 ℃ with agitation (400 rpm) and subsequently exposed to FUS for 30 min. The aggregates were then diluted in high-glucose Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) media (LM001-05, WELGENE, Korea) to prepare 10 μM Aβ solutions. SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells were cultured in growth media consisting of high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS (A5256701, Gibco, USA) and 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (15140122, Gibco, USA) in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Cells were seeded at a density of 1.5 x 104 cells/well in a 96-well cell culture plate (CLS3596, Corning, USA) and incubated for 12 h. After a 4-h serum starvation period, cells were treated with Aβ42 solutions for 12 h. Cell viability was assessed using D-Plus™ CCK cell viability assay kit (Eubiogene, Korea) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Animals

Male B6SJL-Tg(APPSwFlLon,PSEN1*M146L*L286V)6799Vas/Mmjax (5XFAD, MMRRC Strain #034840-JAX) mouse (n = 6) and a female B6SJLF1/J (Strain #100012) mouse (n = 1) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (USA) to establish a breeding colony. Offspring were weaned at 3 weeks of age and separated into transgenic and wild-type groups based on genotyping results. All mice were housed in groups of 4-5 per cage at the Yonsei University animal facility (Seoul, Korea) under controlled temperature and humidity conditions, with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle and ad libitum access to food and water. Age-matched littermates from the same generation were used for the same experiments. The number of mice in each group varied depending on the availability of the experimental animals.

Ex vivo FUS experiment

The 14-month-old female 5XFAD mouse was sacrificed and perfused with 0.9% saline. Brain tissue was then collected and fixed overnight in ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde at 4 °C. Following fixation, the tissue was immersed in 30% sucrose for 24 h and subsequently cut into 25 µm sections using a cryostat at -20 °C (Leica CM1860, Leica, Germany). Each brain slice was mounted at the center of the dish, and the guide cone and dish were filled with degassed water for acoustic coupling. An ultrasound absorber (Aptflex F48, Precision Acoustics, UK) was mounted on the top of the dish to minimize acoustic reflection. Sequentially collected brain slices were symmetrically mounted to facilitate direct comparison of the same plaque. One side of each paired brain slice was exposed to FUS for 30 min. Following exposure, the brain slices were processed for immunostaining for further analysis.

Surgical procedures and experimental setup of the in vivo awake tFUS stimulation

5XFAD mice (11-month-old female, n = 5) were used for this study. Animals were anesthetized via an intraperitoneal injection of a ketamine/xylazine mixture (80 mg/kg ketamine, 10 mg/kg xylazine). An additional dose of anesthetic agent (one-third of the original dose) was administered as needed during surgical procedures. The head of the mouse was held using an adaptor (68014, RWD, China). After the scalp fur was removed, a midline incision was made to expose the skull. The skull surface was cleaned with saline solution and dried for transducer fixation.

A single-element miniature transducer with a 5 mm diameter was placed and secured with cyanoacrylate glue on the skull surface above the left motor cortex (Anterior-posterior (AP): 0 mm; Medial-lateral (ML): 1.5 mm) for transcranial sonication of the focused ultrasound. Dental acrylic cement (Vertex self-curing, Vertex-dental, NL) was additionally used for the fixation of the transducer. After the acrylic cement was cured, the scalp incision was sutured to cover the skull surface, leaving the connector part of the transducer exposed. Animals were allowed to recover for one week before the first experiment.

After recovery, the transducer was connected to the sonication system during stimulation. Mice underwent stimulation five times per week for two weeks, with each session lasting 30 min. Prior to the initial exposure, blood samples were collected via the lateral saphenous vein. After two weeks of stimulation, blood was collected within 10 min following the final session, and brain tissue was harvested.

Histochemistry of brain sections

The brain was coronally sliced into 25 μm sections, and two slides per mouse were used for plaque analysis. The brain sections on glass slides were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution. For antigen retrieval, the slides were soaked in 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in PBS for 10 min and then blocked with 5% goat serum in PBS for 1 h at room temperature to prevent non-specific binding. Primary antibodies diluted in PBS with 5% goat serum were treated for 2 h at room temperature. Fluorescent secondary antibodies diluted in PBS were treated for 1 h at room temperature. Antibodies used in this study were 6E10 (SIG-39320, Biolegend, USA; 1:200), anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) antibody (AB5541, Sigma, USA; 1:300), Alexa Fluor™ 555-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) antibody (A21424, Invitrogen, USA; 1:200), and Alexa Fluor™ 568-conjugated goat anti-chicken IgY (H+L) antibody (A11041, Invitrogen, USA; 1:300). All steps following the secondary antibody treatment were performed in the dark. Thioflavin S (ThS; T1892, Sigma, USA) staining was performed after the 6E10 staining. ThS was diluted in 50% ethanol to make a final concentration of 0.015% and briefly sonicated. Slides were incubated with the ThS solution for 7 min at room temperature, followed by sequential wash with 80% ethanol twice and Milli-Q water twice for 30 s each. After nuclear staining using Hoechst 33342 (10 mg/L; ThermoFisher, USA) for 3 min at room temperature, slides were coverslipped using mounting media (Biomeda, USA) and dried overnight. Images were obtained using a VS200 fluorescence slide scanner (Evident, Japan) and a DM2500 fluorescence microscope (Leica, Germany). Aβ plaques were analyzed using Fiji software [28]. Additionally, Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions using a H&E staining kit (Abcam, UK).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

To detect and quantify the levels of human Aβ42 in plasma, an ELISA was conducted using a human Aβ42 ultrasensitive ELISA kit (Invitrogen, USA) following the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, plasma and CSF samples were prepared by diluting them up to 1:5 fold, respectively, in standard diluent buffer containing a protease inhibitor cocktail. Serial dilutions of the human Aβ42 standard were prepared at the following concentrations: 100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, 3.13, 1.56, and 0 pg/mL. The standards and diluted samples were added to the appropriate wells of the plate. Next, the human Aβ42 detection antibody was added to the wells and incubated overnight at 4 °C. After washing the plate with wash buffer, a secondary antibody (anti-Rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase) was added and incubated for 45 min at room temperature. The wells were then washed, and a chromogen solution was applied to the plate for 30 min in the dark. Finally, a stop solution was added, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a SpectraMax M2 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, USA).

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison tests was used for comparisons among multiple groups. An unpaired t-test was applied for comparisons between two groups, and a paired t-test for comparisons between paired samples in vivo (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001; other comparisons were not significant). Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 10 software. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

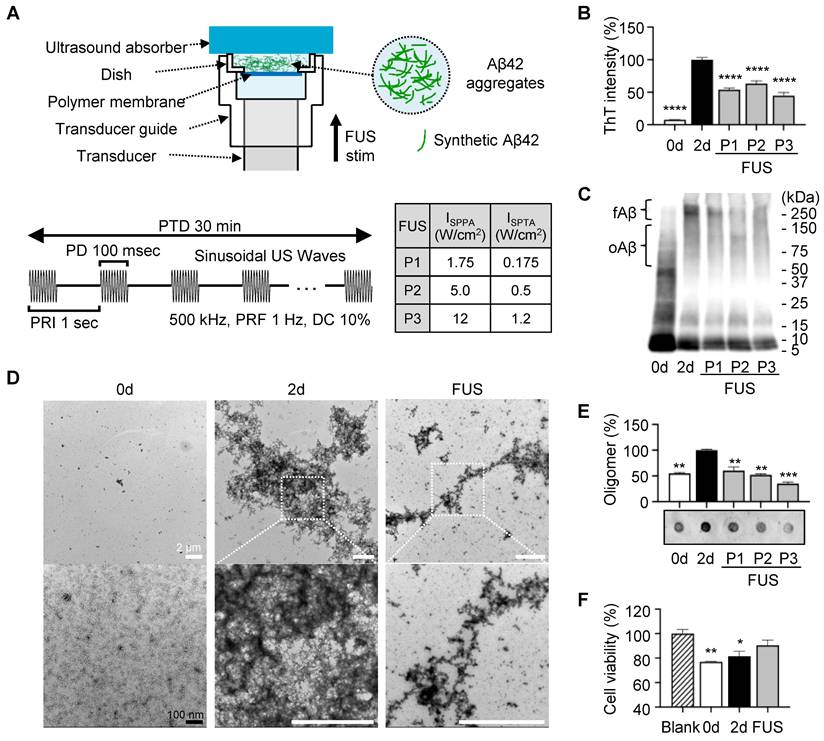

FUS-induced disaggregation of Aβ42 fibrils in vitro

To examine whether FUS disrupts the Aβ assemblies in vitro, we utilized the Aβ42 peptide, which is the most aggregation-prone and pathogenic Aβ isoform in AD [29]. Synthetic Aβ42 peptides were incubated for 2 days at 37 ℃ with agitation to induce self-aggregation, followed by exposure to FUS with three different parameters (P1-P3) (Figure 2A). We first quantified the amount of β-sheet structures by ThT, which emits fluorescence upon binding to them (Figure 2B). During 2-day incubation, β-sheet structures had 13-fold increased (non-incubated Aβ42, 0d; 7.72%). Across P1-P3, ThT fluorescence intensities decreased by 46.14, 36.62, and 55.28%, respectively, compared to the non-sonicated 2-day aggregated control (2d; 100%). Notably, the fibrillar reduction was not relative to the applied FUS intensity, suggesting that the disruption depends on the complicated coordination of acoustic conditions.

To assess FUS-induced alterations in the size distribution of Aβ42 aggregates, we performed sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) combined with PICUP chemistry, which preserves non-covalent assemblies via radical reaction (Figure 2C). We found that protofibril to fibrillar Aβ42 around ~250 kDa (≈55-mer; fAβ) was prominently reduced following FUS, with decreases of 40.24, 62.27, and 52.67% for P1-P3, respectively. These results align with the ThT assay results, indicating a significant reduction of β-sheet-positive high-molecular-weight Aβ42 assemblies by FUS.

Through TEM imaging (Figure 2D, Figure S1), we visualized how FUS affects the fibrillar structure of Aβ42 aggregates. Non-treated 2d control formed dense bundles of fibrils, with intact linkage of thin, needle-like structures at the margins. After FUS exposure, it was revealed that peripheral fibrils fragmented into smaller particles and dispersed, leaving a dense central core.

FUS-induced disaggregation of Aβ42 oligomers in vitro

Because oligomeric Aβ species are considered the most neurotoxic forms of Aβ aggregates, we next assessed whether FUS induced an unexpected increase in oligomer levels due to the fibril disruption. In SDS-PAGE with PICUP chemistry, we revealed that the Aβ42 aggregates with 50~150 kDa (≈10-30-mer; oAβ) decreased by 33.79, 29.16, and 35.36% at P1, P2, and P3, respectively. For another complementary evaluation, dot blot analysis was performed using an oligomer-specific A11 antibody, which is reported to recognize 20~100 kDa oligomers (≈4-22-mer) (Figure 2E, Figure S2) [30]. Consistent with SDS-PAGE analysis, A11-positive oligomer levels were shown to be reduced by 39.53, 47.78, and 65.02% after P1, P2, and P3 treatment, respectively. Together, these findings indicate that FUS did not generate additional neurotoxic oligomers by fibril dissociation; rather, it reduced both fibrils and oligomers.

Finally, we evaluated the consequences of the FUS exposure on Aβ cytotoxicity using the SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells (Figure 2F). The SH-SY5Y cells were treated with non-incubated Aβ42, 2-day-incubated Aβ42 aggregates, and FUS-treated Aβ42 aggregates for 12 h. We found that the non-incubated Aβ42 sample, which is capable of rapidly forming toxic oligomers during the subsequent 12-h incubation, reduced the viability to 76.90%. The 2-day incubated Aβ42 with abundant aggregates reduced viability to 81.56%. In contrast, the FUS-treated Aβ42 sample improved the viability to 90.48%, indicating that FUS attenuated the Aβ42-induced cytotoxicity, as well as the Aβ particles generated after FUS exposure do not re-engage into toxic oligomers over the 12-h incubation. Collectively, we revealed that FUS treatment disrupts Aβ42 aggregates in vitro, especially β-sheet-rich fibrils and oligomers, thereby reducing their cytotoxicity.

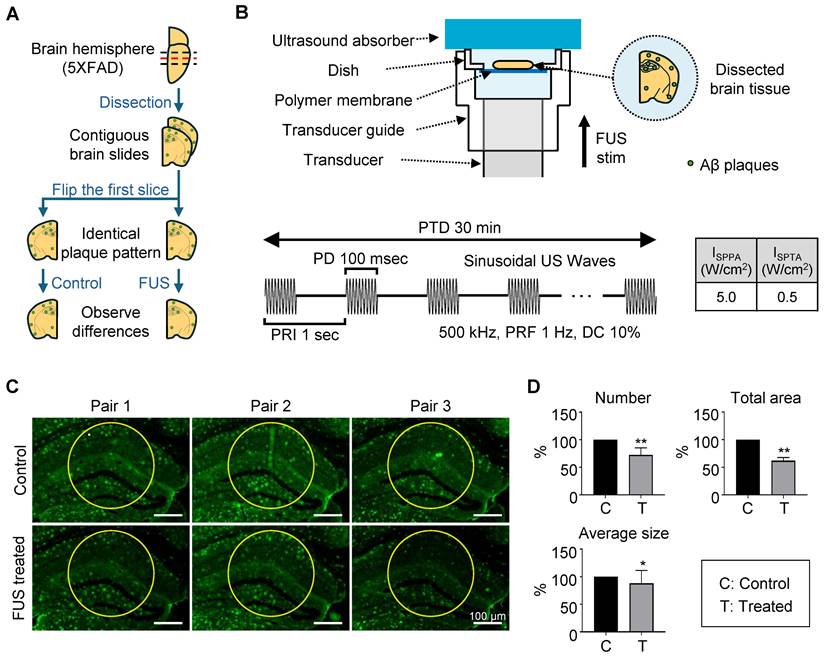

Dissociation of amyloid plaque by FUS treatment ex vivo

For the experiment, 14-month-old 5XFAD mice were sacrificed, and brain tissue was sectioned into 25-μm-thick slices. To directly compare the effects of FUS, the two brain slices were placed symmetrically, each with the same cut surface facing upward (Figure 3A). The tissue was positioned on a polymer-bottomed dish to minimize reflection of acoustic stimulation, with the hippocampus centered. Then the dish was placed on the transducer guide, topped by an ultrasound absorber (Figure 3B). The system was filled with degassed water, and sonication was applied for 30 min using the parameters detailed in Figure 3B. Sonication parameters were selected based on previous studies that demonstrated an effective streaming effect on brain structure induced by sonication [31-33].

Dissociation of Aβ42 fibrils and oligomers by FUS in vitro. (A) Schematic diagram of the FUS-induced synthetic Aβ42 aggregates stimulation setup and temporal features of FUS sonication parameters. (B) ThT fluorescence intensities of FUS (P1-P3)-treated Aβ42 samples with non-incubated (0d) and 2-day incubated (2d) Aβ42 controls. (C) Western blot analysis of Aβ42 samples using 6E10 (1:10,000) antibodies. Aggregates around 250 kDa (≈55-mer) and 50~150 kDa (≈10-30-mer) are marked as fibrillar Aβ42 (fAβ) and oligomeric Aβ42 (oAβ). (D) Representative TEM images of 0d, 2d, and FUS-treated Aβ42 samples. More images are presented in Figure S2. Magnified images of white dashed squares are placed in the row below. White scale bars represent 2 μm, and a black scale bar represents 100 nm. (E) Relative oligomer levels detected using A11 antibody (1:1,500). (F) Viability of SH-SY5Y cells exposed to 0.2% DMSO in DMEM media (blank), 0d, 2d, and FUS-treated Aβ42 samples was evaluated using the CCK cell viability kit (Eubiogene, Korea). One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test was performed for statistical analyses (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, and ****p < 0.0001 vs. 2d in B, E, and Blank in F). Data are presented as the mean of triplicated experiments ± SEM. stim, stimulation.

Dissociation of amyloid plaque ex vivo. (A) Brain sample preparation scheme. The red dashed line indicates the adjacent surface of two consecutive slices, which share an identical plaque pattern and were used in the experiment. Green dots on the brain slide indicate amyloid plaques. (B) Schematic diagram of the FUS-induced brain slice stimulation setup and temporal features of FUS sonication parameters. (C) Brain tissue image after immunohistochemistry using the 6E10 antibody. Yellow circles indicate the analyzed area, with a diameter of 300 μm. (D) Comparison of plaque number, total area, and average size between control and FUS-treated brain tissue. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired t-test (*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01). Data are presented as the mean of triplicated experiments ± SEM. stim, stimulation.

The center of the sonicated region with a diameter of 300 µm of the tissue image was analyzed for measuring the Aβ plaques. (Figure 3C, each area enclosed by the yellow circle). This point was indicated in the acoustic beam profile (Figure 1B-C, white dot), which shows the center of acoustic beam stimulated the target region. Our immunohistochemistry results show that a significant decrease in the number, total area, and average size of the plaques in the hippocampal region was observed after FUS sonication (Figure 3D), compared to the control condition.

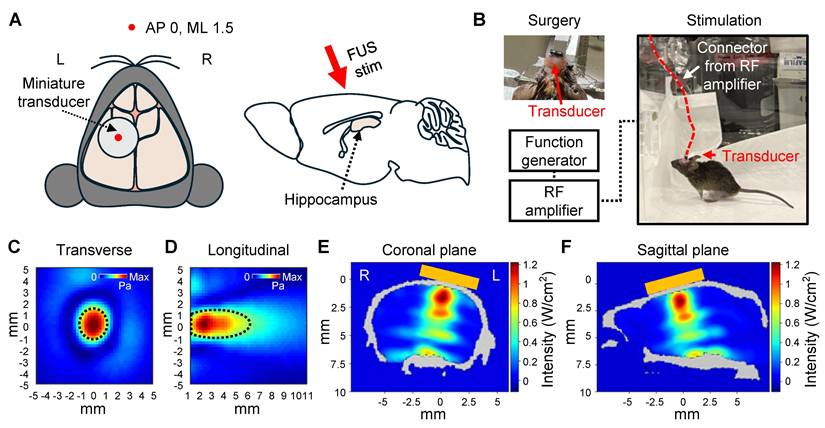

Awake tFUS stimulation

We built a system for in vivo awake tFUS stimulation for 5XFAD mice to investigate the effect of sonication for Aβ plaque dissociation and clearance (Figure 4). A miniaturized transducer specifically designed for in vivo tFUS procedures in awake animals was employed. The transducer had a center frequency of 450 kHz and a diameter of 5 mm. Details regarding the fabrication of the transducer are available in our previous work [34].

The transducer was affixed to the skull to target the left hippocampus (Figure 4A), allowing comparison with the contralateral hippocampal region to assess the effect of sonication. Following the procedure, the mice were given a one-week recovery period to allow the surgical site to heal and to ensure stable attachment of the transducer. As shown in Figure 4B, the animals were freely movable during the 30-minute stimulation session with the transducer and a lightweight connector.

The beam profile of the transducer (Figure 4C-D) and acoustic simulations (Figure 4E-F) demonstrated that sonication was focused on the target region. The parameters for FUS stimulation, such as PRF, PRI, and PTD, were consistent with the ex vivo experiments. However, the operating frequency was set to 450 kHz to match the transducer's center frequency, and the acoustic intensity was reduced (1.75 W/cm2 ISPPA and 0.175 W/cm2 ISPTA) compared to the ex vivo experiment.

The intensities of FUS stimulation were selected to ensure safe brain stimulation according to the FDA's safety guidelines [35] while adapting them to the experimental conditions of the animal model. Considering the acoustic attenuation through the human skull (Fz region of the international 10-10 EEG standard system) [36], a stimulation intensity of 5 W/cm² ISPPA and 0.5 W/cm² ISPTA applied to the human brain is estimated to correspond to approximately 1.25 W/cm² ISPPA and 0.125 W/cm² ISPTA at the target site. This estimated intensity is consistent with the in situ intensity derived from our acoustic simulations.

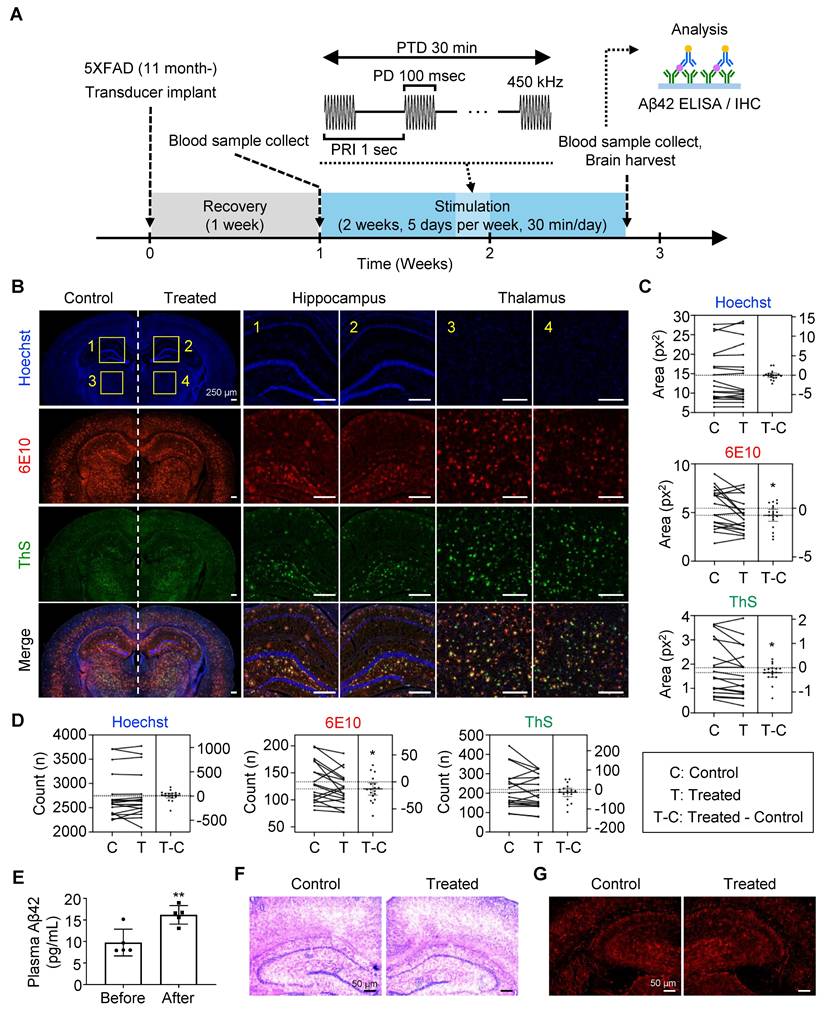

Dissociation of amyloid plaque by FUS treatment in vivo

It was previously reported that mechanically dissociated Aβ plaques were solubilized and cleared via brain-to-blood efflux [37, 38]. To confirm the outflow of Aβ by FUS, we collected plasma from the lateral saphenous vein before FUS treatment (Figure 5A). Each mouse then underwent two weeks of FUS treatment, consisting of five consecutive days of 30-min FUS exposure, a two-day rest period, and another five days of FUS treatment. After the final FUS treatment for 15 min, plasma was collected from the posterior vena cava for comparison, followed by brain tissue collection for further analysis.

When comparing the Aβ deposits in the FUS-treated sides to the non-treated side of the brain (Figure 5B-D, Figure S3), we found a significant reduction in 6E10-positive plaque number and size (p = 0.0284 and 0.0218, respectively) in the targeted hippocampus and the adjacent thalamus by FUS. It was also shown that the size of ThS-positive dense core plaques (p = 0.0327), but not the number (p = 0.1752), is reduced by FUS treatment. Plasma analysis revealed a 65.91% increase in Aβ42 levels after FUS treatment (from 9.758 pg/mL to 16.19 pg/mL, Figure 5E), suggesting that FUS dissociates Aβ plaques, which are subsequently released into the bloodstream. No signs of hemorrhage or inflammation were observed following FUS treatment (Figure 5F-G, Figure S4), as previously reported that the low-intensity FUS is known to have minimal adverse effects [39]. Collectively, we confirmed the disruption and clearance of Aβ plaque by FUS stimulation in vivo.

Setup of in vivo awake tFUS stimulation. (A) Schematic diagram of the transducer fixation (left) and sagittal view (right) of the brain. The red arrow indicates the direction of the tFUS stimulation. (B) Example image of the transducer fixation surgery and in vivo awake stimulation in the mouse. (C-D) Beam profiles of the FUS stimulation along the transverse (C) and longitudinal (D) planes of the focus. The dotted line indicates the FWHM. (E-F) Acoustic simulations of the tFUS stimulation. 2D cross-sectional view from numerical simulation of coronal (E) and sagittal (F) planes is visualized. Orange box indicates the position of the transducer on the skull. L, left hemisphere; R, right hemisphere.

Dissociation and clearance of amyloid plaque in vivo. (A) Experimental timeline and flow of the in vivo plaque dissociation experiment. (B-D) Immunohistochemistry of brain slides for neuron (Hoechst), total plaque (6E10), and dense core plaque (ThS). (B) Representative brain images showing hippocampus (1, 2) and thalamus (3, 4), which were used for neuronal and plaque quantification. Comparison of the plaque (C) size and (D) number between the FUS-treated (Treated, T) and untreated (Control, C) sides of the brain slice. (E) Comparison of plasma Aβ levels before and after FUS treatment. (F) Representative brain tissue image after hematoxylin and eosin staining. (G) Representative brain tissue image after immunohistochemistry with GFAP antibody. Statistical analysis was performed using a paired t-test in C, D, and an unpaired t-test in E (*p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01). IHC, immunohistochemistry.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the potential of FUS as a tool for Aβ plaque dissociation. We found that FUS treatment induced the disruption of fibrillar and oligomeric Aβ42 in vitro. In ex vivo experiments, FUS exposure to brain slices from 5XFAD transgenic mice led to a reduction in Aβ plaque numbers, area, and size within the targeted region. Similarly, in vivo application of FUS over two weeks resulted in a diminished plaque burden. The observed increase in plasma Aβ42 levels further suggests that the dissociated Aβ plaques were cleared into the bloodstream.

Although the precise interactions within amyloid structures remain unclear, previous studies have shown that β-sheet structures of amyloid proteins are characterized by a network of relatively weak interactions, including various types of hydrogen bonding [40]. Based on this feature, we estimated that the application of low-intensity ultrasound mechanical energy may exert sufficient force to dissociate these interactions, potentially leading to the reduction of amyloid plaques. To focus on the mechanical effects of FUS on Aβ aggregates, we performed direct FUS exposure to synthetic Aβ42 aggregates in vitro. FUS stimulation from low (1.75 W/cm2 ISPPA, 0.175 W/cm2 ISPTA) to high (12 W/cm2 ISPPA, 1.2 W/cm2 ISPTA) intensities demonstrated significant breakdown of their β-sheet structure. Next, we adopted stimulation protocols established in previous studies [31, 33]. Our ex vivo experiments demonstrated that mechanical vibration induced by FUS alone was sufficient to reduce the number of accumulated Aβ plaques in the hippocampal region. This indicates a direct physical effect of FUS on aggregated Aβ structures, independent of any neuromodulatory or pharmacological mechanisms.

In the in vivo experiment, we applied a lower intensity (1.75 W/cm2 ISPPA, 0.175 W/cm2 ISPTA) to match the estimated in situ intensity observed through the human skull when delivering 5 W/cm2 ISPPA and 0.5 W/cm2 ISPTA, thereby facilitating clinical translation. Despite the reduced intensity, we still observed a decrease in both the number and size of Aβ plaques. These results suggest that in vivo FUS may exert additional effects beyond direct mechanical dissociation of Aβ plaques, potentially influenced by the structural and systemic environment of the brain. Our previous work using the same PRF, DC, PD, and PTD demonstrated that FUS can enhance CSF circulation, particularly through the perivascular space, and FUS accelerates the movement of nanoparticles that mimic brain waste [33]. The parameters used were also effective in transporting particles through porous structures resembling brain tissue, driven by acoustic forces [31]. These properties suggest that the FUS protocol may enhance CSF clearance mechanisms. Given the CSF-to-blood waste clearance pathway mediated by the perivascular network [41], the observed elevation in plasma Aβ levels after FUS treatment supports this hypothesis, indicating increased washout of amyloid particles from the brain. Taken together, our in vivo results imply a dual mechanism: FUS may first dissociate Aβ aggregates mechanically, followed by enhanced CSF circulation.

FUS has been widely applied in conjunction with microbubbles to safely and reversibly open the BBB [42]. This combined approach offers promising synergistic benefits through two principal mechanisms. First, temporary BBB opening facilitates targeted delivery of therapeutic agents that promote Aβ breakdown [17]. When paired with FUS-mediated mechanical dissociation, such agents may achieve enhanced efficacy against amyloid pathology. Second, increased BBB permeability may activate endogenous clearance pathways, aiding in the removal of amyloid fragments liberated by FUS [14, 43]. These findings collectively underscore the potential of FUS-based strategies as a multifaceted therapeutic approach for AD. However, the possible side effects such as brain edema or microhemorrhage should be considered for applying these combined approaches. Weakened BBB structure of AD patients elevates the risks of opening BBB [44], while FUS dose for mechanical dissociation may require a higher intensity than the safe level for a weakened BBB. For this reason, possible risks should be evaluated while combining BBB opening and enhancing CSF circulation and mechanical dissociation of Aβ plaques. Combined techniques can maximize the reduction of Aβ plaques, while limited and personalized approaches are required, considering personal amyloid pathology and severity.

Beyond vascular effects, microglia play a complex and dualistic role in AD: while contributing to neuroprotection through phagocytic clearance of Aβ plaques, they may also trigger neuronal damage through chronic inflammation [45]. FUS has been shown to modulate microglial activity, potentially biasing their function toward a more beneficial, phagocytic phenotype [46, 47]. Although further investigation is required to fully understand microglial responses under FUS treatment, the enhanced phagocytic activity observed suggests that microglia may contribute to plaque clearance following FUS stimulation, supporting a therapeutic strategy aimed at mitigating disease progression [48].

In the broader therapeutic landscape, the recent FDA approval of anti-Aβ antibody therapies highlights the potential of amyloid-beta clearance in AD [49]. However, these treatments are associated with significant risks, including cerebral edema and hemorrhage, particularly among APOE4 carriers [50]. Moreover, the high cost of antibody therapies presents a challenge for widespread adoption and imposes a burden on public healthcare systems. In contrast, low-intensity FUS has demonstrated a favorable safety profile, and our findings further support its efficacy in reducing amyloid burden. These advantages position FUS as a promising non-invasive alternative to antibody-based therapies.

For the further development of the FUS-mediated Aβ plaques control techniques, personalized dose modulation and stimulation position selection methods can be implemented. We modulated the stimulation dose in consideration with attenuation parameters based on average skull thickness and bone density [36], while moving to the in vivo transcranial stimulation experiments. However, the acoustic attenuation rate could vary by the patient's skull thickness, skull shape, age and bone density [51, 52]. For this reason, personalized sonication protocol in consideration of intensity and stimulation position would be needed for increasing the accuracy of the ultrasound-based treatments. The development of numerical evaluation and neuronavigation techniques based on neuroimaging data can provide guidance for precise control of the FUS stimulation [53, 54]. Although our results demonstrate the efficacy of FUS in reducing amyloid plaque burden, it is important to note that plaque clearance does not necessarily translate into cognitive or behavioral improvement in AD [55]. Future studies should evaluate the impact of FUS on cognitive and behavioral outcomes to fully assess its therapeutic potential. Additionally, a more detailed analysis of Aβ species in vivo, including oligomeric Aβ, may help elucidate the diverse effects of FUS on amyloid pathology and further validate focused ultrasound as a viable treatment strategy. It needed to validate whether FUS parameters could be effectively engineered to target specific Aβ species, which is closely linked to neurotoxicity.

Conclusions

FUS effectively reduces amyloid plaques in both ex vivo and in vivo models, highlighting its potential as a non-invasive strategy for Aβ clearance.

Abbreviations

Abb: Abbreviation

AD: Alzheimer's disease

Aβ: Amyloid-β

AP: Anterior-posterior

APS: Ammonium persulfate

BBB: Blood-brain barrier

CSF: Cerebrospinal fluid

DC: Duty cycle

DMEM: Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium

DMSO: Dimethyl sulfoxide

DTT: Dithiothreitol

ELISA: Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Fmoc: Fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl chloride

FUS: Focused ultrasound

FWHM: Full-width at half-maximum

GFAP: Glial fibrillary acidic protein

HRP: horseradish peroxidase

H&E: Hematoxylin and Eosin

ML: Medial-lateral

PAGE: Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

PBS: Phosphate-buffered saline

PD: Pulse duration

PICUP: photo-induced cross-linking of unmodified protein

PTD: Pulse train duration

PRF: Pulse-repetition frequency

PRI: Pulse repetition interval

SDS: Sodium dodecyl sulfate

SEM: Standard error of the mean

SPPS: Solid-phase peptide synthesis

ISPPA: Spatial-peak pulse-average intensity

ISPTA: Spatial-peak temporal-average intensity

TBST: Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20

TEM: Transmission electron microscope

tFUS: Transcranial FUS

ThS: Thioflavin S

ThT: Thioflavin T

RF: Radio frequency

RuBpy: Tris(2,2-bipyridyl)dichlororuthenium(II) hexahydrate

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures.

Acknowledgements

We thank Hyojun Kim for his technical assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by the KIST Institutional Program (Project No. 2E33771) and a grant of the Korea Dementia Research Project through the Korea Dementia Research Center (KDRC), the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2022-NR072047, RS-2024-00349158), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare and Ministry of Science and ICT, Republic of Korea (Grant Number: RS-2024-00349158), and Mid-Career Researcher Program (Grant Number: NRF-2021R1A2C2093916), and Basic Science Research Program (Grant Number: RS-2018-NR031048) through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare and Ministry of Science and ICT, Republic of Korea, and supported by the National Research Council of Science & Technology(NST) grant by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. GTL25071-000), and supported by Hallym University Research Fund 2024 (HURF-2024-202404230001). This research was also supported by Amyloid Solution.

Authors' contributions

HK, YK and JK (Jaeho Kim) proposed and supervised the project. SL, JK (Jeungeun Kum), and KK designed the study, performed the in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo FUS stimulation, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript with a major contribution. SL managed the mice that performed in vivo FUS stimulation. TYP performed acoustic simulation. HEK participated in ex vivo and in vivo FUS stimulation parameter setup. DLN and SYK provided technical advice. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures of the animal studies were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of laboratory animals (NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 1978) and authorized by the Committee for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals at Yonsei University (Korea, IACUC-A-202302-1640-01).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors.

Competing Interests

YK is an employee of Amyloid Solution and received equity or equity options. Rest of the authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

1. Perl DP. Neuropathology of Alzheimer's disease. Mt Sinai J Med. 2010;77:32-42

2. DeTure MA, Dickson DW. The neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2019;14:32

3. Palop JJ, Mucke L. Amyloid-β-induced neuronal dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease: from synapses toward neural networks. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:812-8

4. Zhang Y, Chen H, Li R, Sterling K, Song W. Amyloid β-based therapy for Alzheimer's disease: challenges, successes and future. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:248

5. van Dyck CH, Swanson CJ, Aisen P, Bateman RJ, Chen C, Gee M. et al. Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer's Disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:9-21

6. Sims JR, Zimmer JA, Evans CD, Lu M, Ardayfio P, Sparks J. et al. Donanemab in Early Symptomatic Alzheimer Disease: The TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2023;330:512-27

7. Espay AJ, Kepp KP, Herrup K. Lecanemab and Donanemab as Therapies for Alzheimer's Disease: An Illustrated Perspective on the Data. eNeuro. 2024 11

8. Honig LS, Barakos J, Dhadda S, Kanekiyo M, Reyderman L, Irizarry M. et al. ARIA in patients treated with lecanemab (BAN2401) in a phase 2 study in early Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2023;9:e12377

9. Greenberg S, Battioui C, Lu M, Biffi A, Ardayfio P, Zimmer J. et al. ARIA Insights from the Donanemab Trials (P1-9.001). Neurology. 2024;102:3339

10. Wang JB, Di Ianni T, Vyas DB, Huang Z, Park S, Hosseini-Nassab N. et al. Focused Ultrasound for Noninvasive, Focal Pharmacologic Neurointervention. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:675

11. Yoo S, Mittelstein DR, Hurt RC, Lacroix J, Shapiro MG. Focused ultrasound excites cortical neurons via mechanosensitive calcium accumulation and ion channel amplification. Nat Commun. 2022;13:493

12. Bashir DJ, Manzoor S, Siddiqui MA, Bashir M, Nidhi, Rastogi S. et al. Nanosized epiberberine-loaded chitosan-collagen nanocomposites: synthesis and evaluation of their cognitive and AChE inhibition enhancing potential in a scopolamine-induced amnesia rat model. New J Chem. 2024 48

13. Bashir DJ, Bhat KA, Bashir M. Deciphering Alzheimer's disease: Molecular mechanisms, preclinical models and strategies to overcome Blood-Brain-Barrier. Brain Res. 2025;1863:149828

14. Rezai AR, Ranjan M, Haut MW, Carpenter J, D'Haese PF, Mehta RI. et al. Focused ultrasound-mediated blood-brain barrier opening in Alzheimer's disease: long-term safety, imaging, and cognitive outcomes. J Neurosurg. 2023;139:275-83

15. Lipsman N, Meng Y, Bethune AJ, Huang Y, Lam B, Masellis M. et al. Blood-brain barrier opening in Alzheimer's disease using MR-guided focused ultrasound. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2336

16. Park SH, Baik K, Jeon S, Chang WS, Ye BS, Chang JW. Extensive frontal focused ultrasound mediated blood-brain barrier opening for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease: a proof-of-concept study. Transl Neurodegener. 2021;10:44

17. Hsu PH, Lin YT, Chung YH, Lin KJ, Yang LY, Yen TC. et al. Focused Ultrasound-Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Opening Enhances GSK-3 Inhibitor Delivery for Amyloid-Beta Plaque Reduction. Sci Rep. 2018;8:12882

18. Lee Y, Choi Y, Park EJ, Kwon S, Kim H, Lee JY. et al. Improvement of glymphatic-lymphatic drainage of beta-amyloid by focused ultrasound in Alzheimer's disease model. Sci Rep. 2020;10:16144

19. Karakatsani ME, Ji R, Murillo MF, Kugelman T, Kwon N, Lao YH. et al. Focused ultrasound mitigates pathology and improves spatial memory in Alzheimer's mice and patients. Theranostics. 2023;13:4102-20

20. Kim E, Kim HC, Van Reet J, Böhlke M, Yoo SS, Lee W. Transcranial focused ultrasound-mediated unbinding of phenytoin from plasma proteins for suppression of chronic temporal lobe epilepsy in a rodent model. Sci Rep. 2023;13:4128

21. Martin E, Aubry JF, Schafer M, Verhagen L, Treeby B, Pauly KB. ITRUSST consensus on standardised reporting for transcranial ultrasound stimulation. Brain Stimul. 2024;17:607-15

22. Lee K, Park TY, Lee W, Kim H. A review of functional neuromodulation in humans using low-intensity transcranial focused ultrasound. Biomed Eng Lett. 2024;14:407-38

23. Treeby BE, Cox BT. k-Wave: MATLAB toolbox for the simulation and reconstruction of photoacoustic wave fields. J Biomed Opt. 2010;15:021314

24. Presotto L, Bettinardi V, Mercatelli D, Picchio M, Morari M, Moresco RM. et al. Development of a new toolbox for mouse PET-CT brain image analysis fully based on CT images and validation in a PD mouse model. Sci Rep. 2022;12:15822

25. Park TY, Pahk KJ, Kim H. Method to optimize the placement of a single-element transducer for transcranial focused ultrasound. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2019;179:104982

26. Estrada H, Rebling J, Turner J, Razansky D. Broadband acoustic properties of a murine skull. Phys Med Biol. 2016;61:1932-46

27. Kim YS, Moss JA, Janda KD. Biological Tuning of Synthetic Tactics in Solid-Phase Synthesis: Application to Aβ(1-42). J Org Chem. 2004;69:7776-8

28. Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:676-82

29. Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer's Disease: Genes, Proteins, and Therapy. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:741-66

30. Ruttenberg SM, Dhaoui R, Kreutzer AG, Nowick JS. Antibodies raised against a structurally defined Aβ oligomer mimic protect human iPSC neurons from Aβ toxicity at sub-stoichiometric concentrations. PLoS One. 2025;20:e0331024

31. Yoo SS, Kim HC, Kim J, Kim E, Kowsari K, Van Reet J. et al. Enhancement of cerebrospinal fluid tracer movement by the application of pulsed transcranial focused ultrasound. Sci Rep. 2022;12:12940

32. Yoo SS, Kim E, Kowsari K, Van Reet J, Kim HC, Yoon K. Non-invasive enhancement of intracortical solute clearance using transcranial focused ultrasound. Sci Rep. 2023;13:12339

33. Choi S, Kum J, Hyun SY, Park TY, Kim H, Kim SK. et al. Transcranial focused ultrasound stimulation enhances cerebrospinal fluid movement: Real-time in vivo two-photon and widefield imaging evidence. Brain Stimul. 2024;17:1119-30

34. Kim E, Anguluan E, Kum J, Sanchez-Casanova J, Park TY, Kim JG. et al. Wearable Transcranial Ultrasound System for Remote Stimulation of Freely Moving Animal. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2021;68:2195-202

35. FDA. Information for manufacturers seeking marketing clearance of diagnostic ultrasound systems and transducers. 2019.

36. Hosseini S, Puonti O, Treeby B, Hanson LG, Thielscher A. A head template for computational dose modelling for transcranial focused ultrasound stimulation. Neuroimage. 2023;277:120227

37. Kim HY, Kim Y. Chemical-Driven Amyloid Clearance for Therapeutics and Diagnostics of Alzheimer's Disease. Acc Chem Res. 2024;57:3266-76

38. Lee D, Kim HV, Kim HY, Kim Y. Chemical-Driven Outflow of Dissociated Amyloid Burden from Brain to Blood. Adv Sci. 2022;9:2104542

39. Pasquinelli C, Hanson LG, Siebner HR, Lee HJ, Thielscher A. Safety of transcranial focused ultrasound stimulation: A systematic review of the state of knowledge from both human and animal studies. Brain Stimul. 2019;12:1367-80

40. Zhai L, Otani Y, Ohwada T. Uncovering the Networks of Topological Neighborhoods in beta-Strand and Amyloid beta-Sheet Structures. Sci Rep. 2019;9:10737

41. Benveniste H, Liu X, Koundal S, Sanggaard S, Lee H, Wardlaw J. The Glymphatic System and Waste Clearance with Brain Aging: A Review. Gerontology. 2019;65:106-19

42. Hynynen K, McDannold N, Vykhodtseva N, Jolesz FA. Noninvasive MR imaging-guided focal opening of the blood-brain barrier in rabbits. Radiology. 2001;220:640-6

43. Leinenga G, Gotz J. Scanning ultrasound removes amyloid-beta and restores memory in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:278ra33

44. van de Haar HJ, Burgmans S, Jansen JFA, van Osch MJP, van Buchem MA, Muller M. et al. Blood-Brain Barrier Leakage in Patients with Early Alzheimer Disease. Radiology. 2016;281:527-35

45. Hansen DV, Hanson JE, Sheng M. Microglia in Alzheimer's disease. J Cell Biol. 2018;217:459-72

46. Grewal S, Goncalves de Andrade E, Kofoed RH, Matthews PM, Aubert I, Tremblay ME. et al. Using focused ultrasound to modulate microglial structure and function. Front Cell Neurosci. 2023;17:1290628

47. Bathini P, Sun T, Schenk M, Schilling S, McDannold NJ, Lemere CA. Acute Effects of Focused Ultrasound-Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Opening on Anti-Pyroglu3 Abeta Antibody Delivery and Immune Responses. Biomolecules. 2022 12

48. Bobola MS, Chen L, Ezeokeke CK, Olmstead TA, Nguyen C, Sahota A. et al. Transcranial focused ultrasound, pulsed at 40 Hz, activates microglia acutely and reduces Abeta load chronically, as demonstrated in vivo. Brain Stimul. 2020;13:1014-23

49. Wu W, Ji Y, Wang Z, Wu X, Li J, Gu F. et al. The FDA-approved anti-amyloid-β monoclonal antibodies for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Med Res. 2023;28:544

50. Abushakra S, Mandelbaum R, Barakos J, Scheltens P, Porsteinsson AP, Watson D. et al. Prevalence of Amyloid-Related Imaging Abnormalities in APOE4/4 Homozygotes with Early Alzheimer's Disease: Baseline Findings from Ongoing Clinical Trials of Oral Anti-Amyloid Agent ALZ-801 (Valiltramiprosate) (P5-6.003). Neurology. 2023;100:3825

51. Gordon MS, Hall MD, Gaston J, Foots A, Suwangbutra J. Individual differences in the acoustic properties of human skulls. J Acoust Soc Am. 2019;146:EL191-EL7

52. Riis TS, Webb TD, Kubanek J. Acoustic properties across the human skull. Ultrasonics. 2022;119:106591

53. Park TY, Kim H-J, Park SH, Chang WS, Kim H, Yoon K. Differential evolution method to find optimal location of a single-element transducer for transcranial focused ultrasound therapy. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2022;219:106777

54. Park TY, Koh H, Lee W, Park SH, Chang WS, Kim H. Real-Time Acoustic Simulation Framework for tFUS: A Feasibility Study Using Navigation System. NeuroImage. 2023;282:120411

55. Morris GP, Clark IA, Vissel B. Inconsistencies and Controversies Surrounding the Amyloid Hypothesis of Alzheimer's Disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2014;2:135

Author contact

![]() Corresponding authors: Jaeho Kim, Phone: +82-31-8086-2310 Fax: +82-50-4068-1402 E-mail: ion8484com. YoungSoo Kim, Phone: +82-32-749-4523 Fax: +82-32-749-4105 E-mail: y.kimac.kr. Hyungmin Kim, Phone: +82-2-958-5695 Fax: +82-2-958-5629 E-mail: hkre.kr.

Corresponding authors: Jaeho Kim, Phone: +82-31-8086-2310 Fax: +82-50-4068-1402 E-mail: ion8484com. YoungSoo Kim, Phone: +82-32-749-4523 Fax: +82-32-749-4105 E-mail: y.kimac.kr. Hyungmin Kim, Phone: +82-2-958-5695 Fax: +82-2-958-5629 E-mail: hkre.kr.

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact