13.3

Impact Factor

Theranostics 2026; 16(5):2357-2371. doi:10.7150/thno.125880 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Hollow RuO2 nanozymes sensitized by carbon dot sonosensitizers for sonodynamic/chemodynamic-activated immunotherapy

1. Department of General Surgery, Second Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei, Anhui 230601, China.

2. School of Environmental and Chemical Engineering, Shanghai University, Shanghai 200444, China.

*Equal contributions.

Received 2025-9-26; Accepted 2025-11-10; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

Background: Regulating the morphology structure of sonosensitizers and nanozymes is crucial to improve sonodynamic and enzyme-mimic activities.

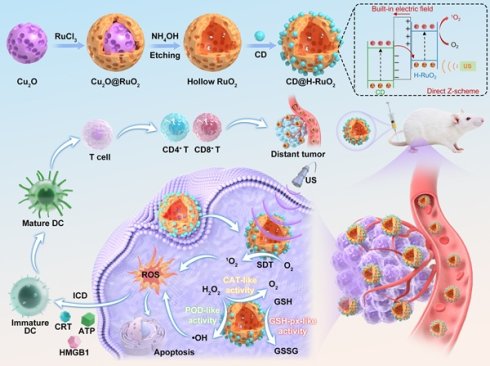

Methods: We report for the first time the utilization of Cu2O nanospheres as the sacrificial templates for the synthesis of hollow RuO2 nanospheres (H-RuO2) for high-efficiency sonodynamic and chemodynamic therapy (SDT/CDT). We then utilized NIR phosphorescence carbon dots (CDs) as the auxiliary sonosensitizers to sensitize H-RuO2 for the construction of CD@H-RuO2 heterojunctions.

Results: Compared with solid nanoparticles, nanosheets, and other structures, the hollow RuO2 (H-RuO2) nanostructures are expected to exhibit stronger catalytic activity due to their larger specific surface area and more catalytic active sites. The improved electron-hole separation kinetics enable CD@H-RuO2 nanozymes with significantly enhanced sonodynamic and multienzyme-mimic activities. CD@H-RuO2-triggered cascade amplification of antitumor immune response was realized by the heterojunction construction, GSH depletion, and relief of hypoxia co-augmented ROS yield, which significantly induced a robust ICD.

Conclusion: CD@H-RuO2-mediated SDT and CDT co-amplified immunotherapy have shown significant antitumor effects, resulting in the eradication of primary tumors and the inhibition of distant tumor growth. This study offers hopeful insights into the fabrication of heterojunctions for sonodynamic/chemodynamic-activated immunotherapy

Keywords: carbon dots, hollow RuO2 nanospheres, heterojunctions, sonodynamic therapy, immunotherapy

Introduction

The treatment of colorectal cancer is highly challenging due to its high heterogeneity (diverse genetic mutations) and hidden risk of metastasis [1-3]. To address colorectal cancer, a range of anticancer approaches like surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and targeted therapy can be used, but there is a critical need for more powerful strategies, particularly for advanced stages of the disease [4]. Cancer immunotherapy has emerged as a promising approach for treating cancer. However, traditional chemotherapy and radiotherapy fail to generate a lasting immune response [5-8]. In the treatment of colorectal cancer, the use of programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors as part of immune checkpoint blockade (ICB)-mediated tumor therapy has increased [9-11]. Nevertheless, due to low PD-L1 expression levels and impaired immune responses in the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME), a considerable number of patients have insufficient responses to ICB-induced tumor treatment [12-14]. Additionally, patients receiving αPD-L1 monotherapy often develop different degrees of drug resistance or experience immune-related adverse reactions, ultimately affecting treatment outcomes [15-17]. Given this situation, the development of innovative immunomodulatory strategies is essential to overcome the limitations of existing immunotherapy.

The emergence of immunogenic cell death (ICD) has opened up a new perspective for immunotherapy [18-21]. However, the high toxicity and poor tolerance of chemotherapeutic drugs such as doxorubicin have limited their clinical application in inducing ICD [22, 23]. Recently, various therapeutic strategies that use reactive oxygen species (ROS) to kill tumor cells and enhance immune responses have been developed, including sonodynamic, photodynamic, and chemodynamic therapy (SDT/PDT/CDT) [14, 24-29]. Among them, sonodynamic therapy (SDT) has a higher penetration depth and can overcome the limitations of photodynamic therapy (PDT), effectively targeting tumors at different depths in the body [30-34]. However, the limited ROS generation efficiency of sonosensitizers significantly restricts the effect of SDT-induced ICD. These sonosensitizers typically have wide bandgaps and rapid electron-hole recombination [35-40]. Moreover, the intricate TME, defined by hypoxia and increased GSH expression, plays a crucial role in influencing the effectiveness of SDT [41-43]. Hence, it is crucial to investigate high efficiency sonosensitizers and control immunosuppressive TME to increase ROS production and enhance ICD effectively.

Combining the SDT-triggered ROS production with other theranostic approaches that support ICD is necessary for a comprehensive activation of the immune response. CDT employs nanozymes for inducing endogenous catalytic reactions in TME, leading to the selective generation of ROS for cancer cell destruction, demonstrating both precise targeting and minimal toxicity [44-46]. In addition, CDT can induce strong ICD without external energy, leading to an antitumor immune response and the ability to overcome drug resistance [47-49]. Moreover, nanozymes exhibiting GSH-px-like and CAT-like activities can regulate the immunosuppressive TME and achieve cascade amplification of ROS production by decreasing the overexpressed GSH and increasing the production of O2 [50-52]. However, the vast majority of nanozymes have low catalytic activity, and it is difficult to achieve complete eradication of tumors with a single CDT [53-57]. Although some Cu-based nanozymes have high catalytic activity, the extreme toxicity of Cu+ often causes irreversible damage to normal tissues due to the inevitable leakage of nanodrugs [58, 59]. In addition, previous reports have not yet focused on controlling the morphology of nanozymes to achieve rational regulation of their catalytic activity.

RuO2 has been widely used in fields such as biosensing, disease treatment, and environmental catalysis due to its excellent catalytic activity, high stability, and controllability [60, 61]. Compared with the highly toxic Cu2O with uncontrolled ion leaching, RuO2 exhibited excellent biocompatibility [62]. Compared with other widely studied metal oxide nanozymes such as manganese dioxide (MnO2) and cerium dioxide (CeO2), ruthenium dioxide (RuO2) has obvious advantages in in vivo therapeutic applications. Its excellent chemical stability significantly reduces the risk of toxic ion leakage, solving the potential long-term biosafety issues related to manganese or cerium ions. Furthermore, the mixed-valence states of Ru (Ru3+/Ru4+) endow it with multifaceted enzyme-mimicking activities, including POD-like and GSH-oxidase-like activities, which are crucial for synergistic CDT and TME regulation. In addition, its suitable bandgap structure makes it an ideal candidate for constructing heterojunctions to augment sonodynamic performance. Although the catalytic activity of RuO2 is weaker than that of unstable and easily oxidizable Cu2O, its good biocompatibility and stable catalytic activity make it more suitable for nanocatalytic reactions compared to Cu2O. Based on this situation, it is crucial to regulate the morphology and structure of RuO2 to enhance its catalytic activity. Compared with solid nanoparticles, nanosheets, and other structures, the hollow RuO2 (H-RuO2) nanostructures are expected to exhibit stronger catalytic activity due to their larger specific surface area and more catalytic active sites [61]. Nevertheless, the use of H-RuO2 as nanozymes or sonosensitizers for CDT and SDT has not been previously reported.

In this work, we first utilized Cu2O nanospheres as the sacrificial templates for the synthesis of H-RuO2 nanospheres for high-efficiency CDT and SDT. The ingenious design of H-RuO2 structure is reflected in the choice of sacrificial templates. On the one hand, Cu2O is highly chemically reactive and prone to oxidation, indicating that its surface has many active sites that can efficiently adsorb and deposit metal ions. In contrast, the commonly used SiO2 templates require additional reducing agents or surface modifications to facilitate the deposition of metal oxides, leading to a more complex procedure and potential impurity introduction [63]. On the other hand, the removal of Cu2O can be achieved through a mild etching with weakly alkaline ammonia water at room temperature within a short timeframe. Conversely, removing SiO2 often necessitates prolonged exposure (over 12 hours) to strong acids (e.g., HCl, HF) or bases (e.g., NaOH, KOH) under heating conditions [64], which may erode the deposited metal oxides due to the aggressive nature of these chemicals. On this basis, Cu2O nanospheres were selected as the templates for the synthesis of H-RuO2 nanospheres. As expected, the obtained H-RuO2 nanospheres exhibit good sonodynamic and multienzyme-mimic activities.

To further improve the sonodynamic and multienzyme-mimic activities of H-RuO2, we utilized NIR phosphorescence CDs as the auxiliary sonosensitizers to sensitize H-RuO2 through coating CDs on H-RuO2. CD@H-RuO2 can act as heterojunction nanozymes and exhibit enhanced sonodynamic and multienzyme-mimic activities owing to the improved electron hole separation kinetics. Upon accumulation in tumor tissue, CD@H-RuO2 produced abundant ROS through the synergistic effect of SDT and CDT. The antitumor immune response triggered by CD@H-RuO2 can be further amplified from the following aspects. Firstly, the synergistic SDT and CDT through CD@H-RuO2 nanozymes can generate ROS for triggering ICD. Secondly, the SDT performance facilitated by CD@H-RuO2 was boosted even further by the reduction of hypoxia, resulting in an increased supply of O2 for SDT. Thirdly, the ROS-induced ICD may be intensified due to the increased ROS generation caused by the reduction of GSH. Satisfactory therapeutic outcomes for primary and distant tumors were obtained by CD@H-RuO2-mediated sonodynamic/chemodynamic-activated immunotherapy (Scheme 1).

Schematic illustration of the preparation of CD@H-RuO2 heterojunctions for sonodynamic/chemodynamic-activated immunotherapy. Cu2O nanospheres were utilized as the sacrificial templates for the synthesis of H-RuO2, which was then sensitized by CD sonosensitizers for enhanced SDT and CDT.

Results and Discussion

The synthesis process of the Z-type CD@H-RuO2 heterojunction was illustrated in Scheme 1. The Cu2O nanospheres were synthesized via a straightforward wet-chemical approach. TEM image of Cu2O nanospheres illustrated in Figure S1A revealed uniformly dispersed nanospheres with an average diameter of approximately 150 nm. High-resolution TEM image further indicated the lattice spacings of 0.254 nm and 0.207 nm, corresponding to the (200) and (111) crystal planes of Cu2O, respectively (Figure S1b). When Cu2O nanospheres are introduced into the RuCl3 solution, surface-exposed Cu+ ions promptly donate electrons to Ru3+ in solution. The reduced Ru species subsequently undergo hydrolysis or oxidation at the Cu2O interface, forming hydrated RuO2 (RuO2·xH2O), which deposits epitaxially to build a continuous shell. This transformation initiates at the outer surface of the Cu2O spheres and progresses outward, ultimately yielding a well-defined RuO2 shell. As shown in Figure 1A, the RuO2 shell is uniformly coated on the surface of Cu2O. Due to the partial etching of Cu2O during the deposition process, its size change is extremely small. The subtle size change of Cu2O@RuO2 compared with the original Cu2O was further confirmed by DLS measurements (Figure 1G), indicating that the hydrodynamic diameters of Cu2O@RuO2 and Cu2O were determined to be 197.6 nm and 205.4 nm, respectively. We also detected the XRD patterns and XPS spectra of Cu2O@RuO2 and Cu2O. As depicted in Figure S2, no significant change of diffraction peaks can be detected in Cu2O core before and after RuO2 shell deposition. The absence of RuO2-related peaks in the XRD pattern can be attributed to the relatively low synthesis temperature (80°C), which resulted in an amorphous/defective nature of H-RuO2. The survey XPS spectrum depicted in Figure S3A revealed the presence of Cu and Ru, demonstrating the successful coating of RuO2 shell. We also detected the existence of Ru4+, Ru3+, Cu+, Cu2+, and O-H in Cu2O@RuO2 (Figures S3B-D).

Subsequently, the Cu2O core was selectively removed using ammonia water etching method, yielding the hollow RuO2 structure. The TEM image revealed the hollow structure of H-RuO2 (Figure 1B). The poor crystalline of H-RuO2 was then verified by the XRD pattern (Figure 1H). By comparing with the standard PDF card of RuO2, we found that the diffraction peak at 35° and 55° could be attributed to RuO2. However, it presented a very broad diffraction peak, indicating that H-RuO2 exhibits an amorphous nanocrystalline structure. Before and after Cu2O etching, the size of H-RuO2 did not exhibit obvious changes (Figure 1F). After etching, Ru4+, Ru3+, and O-H were also presented in the XPS spectrum of H-RuO2 (Figure S4), suggesting the successful preparation of H-RuO2. We also found the positively charged features of H-RuO2, suggesting that H-RuO2 could bind to nanomaterials with negatively charged characteristics.

(A-C) TEM images of Cu2O@RuO2, H-RuO2, and CD@H-RuO2. (D) HRTEM of CD@H-RuO2. (E) Ultraviolet-visible absorption spectra of H-RuO2, CD and CD@H-RuO2. (F, G) Zeta potential and hydrodynamic diameter of Cu2O, Cu2O@RuO2, H-RuO2 and CD@H-RuO2. (H) XRD patterns of H-RuO2, CD and CD@H-RuO2. (I-L) Survey XPS (I), high-resolution Ru 3p (J), N 1s (K), O 1s (H), S 2p (L) spectra of CD@H-RuO2. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. (n = 3).

We then synthesized negatively charged CDs with long-lived triplet state through a simple microwave method according to our previous reports [40, 65]. A lattice spacing of 0.21 nm was revealed in the high-resolution TEM image, demonstrating the successful preparation of CDs (Figure S5). XRD pattern presented in Figure 1H also verified the successful synthesis of CDs, which exhibited a broad diffraction peak at approximately 22°. XPS spectrum illustrated in Figure S6 indicated that CDs contained sulfonic acid group, which endowed CDs with negatively charged features. The negatively charged characteristics of CDs were confirmed by the Zeta potential measurements (Figure 1F). In addition, the presence of pyrrolic N in CDs was also demonstrated by the XPS measurements, which suggested that the possible binding mode between CDs and H-RuO2 was Ru-N coordination bond.

Finally, the negatively charged CDs were electrostatically adsorbed onto the positively charged H-RuO2 surface, forming the Z-type CD@H-RuO2 heterojunctions. A series of characterization experiments were conducted to confirm the successful synthesis of CD@H-RuO2. TEM image indicated that the surface of H-RuO2 was coated with CDs (Figure 1C), which also indicated that the size of CD@H-RuO2 was slightly larger than that of the pristine H-RuO2. The increased size of CD@H-RuO2 compared with H-RuO2 was also demonstrated by the DLS measurements (Figure 1G). High-resolution TEM image of CD@H-RuO2 revealed a lattice spacing of 0.21 nm corresponding to CDs (Figure 1D), while no distinct lattice fringes associated with H-RuO2 were observed, suggesting its amorphous/defective crystalline structure. Furthermore, through the EDS element mapping analysis, it was further determined that CD@H-RuO2 is composed of Cu (3.51 at.%), Ru (19.63 at.%), N (6.87 at.%), O (68.00 at.%) and S (1.99 at.%). The low copper content indicates that Cu2O has been almost completely etched. (Figure S7). UV-vis absorption spectroscopy exhibited that H-RuO2 possessed a flat horizontal absorption profile, whereas after loading CDs, the absorption spectrum underwent significant alterations (Figure 1E). Furthermore, as shown in Figure 1F, the Zeta potential of positively charged H-RuO2 becomes negative after loading carbon dots. XRD analysis further confirmed the structural evolution during synthesis. In the XRD pattern of CD@H-RuO2 (Figure 1H), a diffraction peak appeared at approximately 22°, corresponding to the [002] crystal plane of the graphite-like structure of CDs. As shown in Figure 1I, CD@H-RuO2 was primarily composed of five elements: C, N, O, S, and Ru. The XPS signal of Ru 3p was deconvoluted into four peaks: two peaks located at 463.5 eV and 485.8 eV correspond to Ru4+, while the other two peaks at 466.4 eV and 488.5 eV are associated with Ru3+ (Figure 1J). Nitrogen in the forms of pyrrole nitrogen and graphite nitrogen are the predominant forms in the N 1s spectrum of CD@H-RuO2, furthermore, the new peak fitted at 397.8 eV can be attributed to the Ru-N bond (Figure 1K), whereas sulfur mainly exists as sulfonic acid groups and the several peaks fitted in the C1s XPS can be respectively attributed to C-C/C=C, C-O, C-N and C-S bonds (Figures 1L and S8). Collectively, these results confirmed the successful loading of CDs onto the surface of H-RuO2. CD@H-RuO2, CDs, and H-RuO2 were placed in PBS and RPMI-1640 culture medium, and their behaviors over different time periods were monitored. As presented in Figure S9, the DLS results revealed that the size of CD@H-RuO2 remained nearly unchanged after storage for various durations in either PBS or RPMI-1640 solution, demonstrating its good colloidal stability. In contrast, H-RuO2 exhibited a gradual increase in size after storing in PBS or RPMI-1640 solution, which could be ascribed to the aggregation of H-RuO2. The enhanced stability of CD@H-RuO2 can be attributed to the excellent biocompatibility of CDs, which formed a stable surface modification layer on H-RuO2. The hydrophilic functional groups on the surface of CDs substantially improved the colloidal stability of the composite material.

After confirming the successful preparation of the CD@H-RuO2 Z-type heterojunctions, we further investigated their amplified sonodynamic activity. To evaluate the generation of ROS, we employed DPBF as a ROS probe. We evaluated the sonodynamic activity of CD@H-RuO2 prepared at different mass ratio of CD to H-RuO2. We found that the highest sonodynamic activity of CD@H-RuO2 can be achieved at the mass ratio of CD to H-RuO2 of 2 : 1 (Figure S10). Further increasing the mass ratio to 4 : 1 resulted in negligible enhancement in sonodynamic activity, likely because the adsorption capacity of H-RuO2 toward CDs had already been saturated. Compared with H-RuO2 without CDs deposition (Figure 2A) and CDs alone (Figure 2B), CD@H-RuO2 exhibited significantly enhanced ROS production under US irradiation (Figure 2C). The degradation rate constant of DPBF for CD@H-RuO2 was found to be 0.123 min-1, surpassing that of H-RuO2 (0.086 min-1) by 1.43 times and that of CDs alone (0.069 min-1) by 1.78 times (Figure 2D). These results indicated that the construction of the Z-type heterojunctions effectively suppressed the recombination of electron-hole pairs. To further confirm the generation of ROS, ESR measurements were conducted using TEMP as the 1O2 scavenger to detect the ROS production capacity of CD@H-RuO2, H-RuO2, and CDs. As shown in Figure 2E, the ESR signal intensity of CD@H-RuO2 is stronger than that of H-RuO2 and CDs alone. Therefore, the incorporation of CDs into H-RuO2 enhances its sonodynamic performance, which may be attributed to the enhanced carrier transfer within the Z-scheme heterojunction.

To clarify the potential mechanism of the enhanced sonodynamic performance of the CD@H-RuO2 Z-scheme heterojunction, Firstly, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were conducted on H-RuO2, CD and CD@H-RuO2. As shown in Figure S11, the charge transfer resistance of the CD@H-RuO2 Z-scheme heterojunction is lower than that of each individual component, indicating that the construction of heterojunction enhanced the interfacial charge transfer efficiency. Next, we calculated the band gap widths of H-RuO2 and CDs, which were 1.60 eV (Figure 2F) and 1.73 eV (Figure 2G), respectively. Additionally, XPS-VB analysis revealed that the valence band position of H-RuO2 was 0.91 eV (Figure 2H), while that of CDs was 1.94 eV (Figure 2I). Based on these data, we constructed the band alignment diagram of the CD@H-RuO2 heterojunction (Figure 2J). Considering the surface charge characteristics, an internal electric field prevented electron transfer from positively charged H-RuO2 to negatively charged CDs. Conversely, the internal electric field assists in the electron transfer from the conduction band of CDs to the valence band of H-RuO2, confirming the formation of a Z-type heterojunctions in the CD@H-RuO2 composites (Figure 2K). Such interfacial charge transfer significantly prolonged the carrier lifetime and inhibits electron-hole recombination. From a thermodynamic perspective, the CB potential of H-RuO2 (-0.69 eV) is much more negative than the O2/O2- redox potential (-0.33 V vs. NHE), favoring the efficient generation of ROS.

(A-C) Ultraviolet-visible absorption spectra of DPBF indicated the ROS generation capability of H-RuO2, CD and CD@H-RuO2. (D) Quantitative fitting of reactive oxygen species generation rates of H-RuO2, CD and CD@H-RuO2. (E) Detection of Singlet Oxygen Generation from H-RuO2, CD and CD@H-RuO2 by ESR Spectroscopy. (F-I) Determination of the bandgap and valence band spectrum of H-RuO2 and CDs. (J, K) Illustrations of the energy band diagrams of the Z-type CD@H-RuO2.

(A-D) Ultraviolet-visible absorption spectrum and quantitative fitting indicated the CDT activity of CD@H-RuO2, H-RuO2 and CD at pH 6.0. (E-H) Ultraviolet-visible absorption spectrum and quantitative fitting indicated the CDT activity of CD@H-RuO2, H-RuO2 and CD at pH 6.5. (I-L) Measurements of GSH consumption of CD@H-RuO2 and H-RuO2. (M, N) Evaluation of O2 production of CD@H-RuO2 and H-RuO2. (O) Schematic diagram of catalytic reactions of CD@H-RuO2.

Given the presence of Ru3+ in CD@H-RuO2, we employed TMB as a probe to investigate the CDT activity of the Z-type heterojunctions of CD@H-RuO2 based on the catalytic effect of Ru3+ on the Fenton-like reaction of H2O2. At pH 6.0, as the concentration of H2O2 increased, the absorbance at 652 nm for both CD@H-RuO2 and H-RuO2 significantly rose (Figures 3A, B). CD@H-RuO2 showed a rate constant of 0.413 min-1 for •OH generation, while H-RuO2 exhibited a rate constant of 0.363 min-1 (Figure 3D), indicating that CD@H-RuO2 exhibited the higher Fenton-like catalytic activity. This is attributed to the heterojunction structure, which facilitates efficient separation and directional migration of electron-hole pairs via an interfacial built-in electric field, thereby effectively suppressing charge recombination and increasing the availability of reactive electrons for peroxidase-like or catalase-like reactions. Meanwhile, the interface electronic reconstruction optimizes the adsorption energy of reaction intermediates, enabling the complementary catalytic functions of multiple components to be coordinated and exposing more active sites. These combined effects enhance catalytic efficiency [68, 69]. Additionally, the enzyme catalytic rate constant further confirms this. As shown in Figure S12, the calculated Vmax of CD@H-RuO2 is 2.32×10-7 M s-1, slightly higher than that of H-RuO2 at 2.22×10-7 M s-1, while its Km value is 3.69 mM, slightly lower than that of H-RuO2 at 4.16 mM. These kinetic parameters indicate an improvement in both substrate affinity and catalytic efficiency, suggesting superior enzymatic activity. Moreover, a comparative analysis with previously reported nanozymes further validates the outstanding peroxidase-like activity of CD@H-RuO2 (Table S1). In contrast, under the same conditions, CDs showed no POD activity (Figure 3C). At pH 6.5, the hydroxyl radical generation rates of CD@H-RuO2 (Figure 3E) and H-RuO2 (Figure 3F) were both lower than those at pH 6.0 (Figure 3H). Notably, no obvious POD activity was observed for the three materials at pH 7.4 (Figure S13), indicating that CD@H-RuO2 and H-RuO2 would not exhibit toxicity to normal tissues with physiological pH values. Furthermore, the superior CDT activity of CD@H-RuO2 and H-RuO2 was further confirmed by ESR spectra using DMPO as a hydroxyl radical scavenger (Figure S14). These results collectively demonstrate that the CDT activity of CD@H-RuO2 and H-RuO2 has pH-responsive characteristics, highlighting their potential for tumor-specific therapeutic applications.

Furthermore, we investigated the ability of CD-H-RuO2 to consume GSH. After incubation with GSH for different periods of time, the characteristic absorption peaks of DTNB in CD@H-RuO2 (Figure 3I) and H-RuO2 solution (Figure 3K) were significantly reduced, indicating that these materials could effectively consume GSH. In contrast, pure CDs did not have the ability to consume GSH (Figure S15). After 6 hours of incubation, CD@H-RuO2 and H-RuO2 almost consumed all of the GSH (Figures 3J, L), which indicated that CD@H-RuO2 had a stronger ability to consume GSH, thereby enhancing the efficiency of ROS generation. In addition, oxygen plays a crucial role in SDT as they contribute to the generation of ROS. Therefore, we investigated the ability of CD@H-RuO2 to catalyze the generation of oxygen from H2O2. As shown in Figure 3M, the oxygen generation capacity of CD@H-RuO2 and H-RuO2 is comparable, while CDs exhibit almost no oxygen generation activity. As depicted in Figure 3N, the amount of oxygen generated gradually increases with the increase in H2O2 concentration, confirming its dependence on H2O2. These results collectively indicate that the CD@H-RuO2 heterojunction exhibits excellent TME-responsive properties. It can effectively utilize the excessive H2O2 in the TME to generate highly cytotoxic •OH radicals, while simultaneously generating oxygen to alleviate the hypoxic condition of tumors, thereby enhancing the efficacy of SDT. Additionally, its superior glutathione depletion performance prevents the excessive clearance of ROS, thereby maximizing the amplification effect of ROS and therapeutic efficacy (Figure 3O).

Based on the excellent sonodynamic and chemodynamic activities of CD@H-RuO2, we assessed the combined antitumor effects of CD@H-RuO2 in SDT/CDT therapy at the cellular level. Mouse embryonic fibroblast NIH-3T3 and mouse colorectal cancer CT-26 cells were used as cellular models. Different concentrations of CD@H-RuO2, H-RuO2, and CD were incubated with NIH-3T3 cells, and the cell survival rate remained consistently above 90%. This phenomenon indicated that CD@H-RuO2, H-RuO2, and CD exhibited good biocompatibility (Figures 4A, B, and S16A). To evaluate the antitumor efficacy of the combined SDT and CDT treatment mediated by the Z-type heterojunction of CD@H-RuO2, cytotoxicity experiments were conducted using CT-26 cells. Regarding the single CDT-mediated antitumor effects via CD@H-RuO2 and H-RuO2, both materials exhibited low cytotoxicity when used alone to stimulate CT26 cells. Even at a concentration of 100 μg/mL, the survival rates of cancer cells were 76.9% for H-RuO2 and 72.5% for CD@H-RuO2, indicating that single CDT treatment was insufficient to completely eradicate cancer cells. In contrast, CD alone showed negligible toxic side effects on CT-26 cells (Figure S16B). For the in vitro synergistic CDT-SDT treatment effect of CD@H-RuO2, after US irradiation, the survival rates of CT-26 cells treated with H-RuO2 and CD@H-RuO2 were significantly reduced. Specifically, the survival rate of CT-26 cells decreased to approximately 33.9% after H-RuO2+US treatment (Figure 4C), while it dropped dramatically to 3.13% after CD@H-RuO2+US treatment (Figure 4D). To demonstrate the synergistic effect between CDT and SDT, we utilized mannitol to scavenge •OH generated by CDT. As illustrated in Figure S17, the "CD@H-RuO2 + mannitol" group represented no SDT and CDT. The "CD@H-RuO2" represented CDT alone. The "CD@H-RuO2 + mannitol + US" group represented SDT alone. The "CD@H-RuO2 + US" group represented the combined SDT and CDT. We then utilized MTT assay to evaluate the cell viability of CT26 cells after different treatments. The results indicated that CD@H-RuO2 exhibited negligible cytotoxicity against CT26 cells in the no SDT/CDT group. In contrast, CDT alone and SDT alone induced 28% and 67% cell death, respectively. Notably, when CDT and SDT were combined, CD@H-RuO2 achieved nearly complete (almost 100%) elimination of CT26 cells. Additionally, we conducted live/dead staining experiments to compare six different treatment methods: control, US, H-RuO2, CD@H-RuO2, H-RuO2 + US, and CD@H-RuO2 + US. As shown in Figure 4F, the proportion of dead cells in the CD@RuO2 + US group was significantly higher than in the other groups.

Then, we employed the DCFH-DA probe to stain CT-26 cells after different treatments to evaluate intracellular ROS levels. Figure 4G demonstrated that there was no significant green fluorescence signal in CT-26 cells treated with PBS or US alone. On the other hand, there was a slight green fluorescence indicating ROS generation in the H-RuO2 and CD@H-RuO2 groups, possibly due to the Ru3+-mediated Fenton-like catalytic reaction. Furthermore, when exposed to US irradiation, the CD@H-RuO2 Z-type heterojunction showed a notably stronger green fluorescence signal in comparison to the pristine H-RuO2, further demonstrating that the construction of the Z-type heterojunction enhanced ROS generation. In addition, extensive studies have shown that excessive ROS can lead to mitochondrial damage and apoptosis. Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) is highly sensitive to the accumulation of ROS in mitochondria. We used JC-1 as a probe to detect the changes in MMP in CT26 cells after six different treatments. The shift from red fluorescence to green fluorescence is a sign of mitochondrial dysfunction. According to confocal images (Figure 4H), the CD@H-RuO2 + US group showed the strongest green fluorescence and the weakest red fluorescence, indicating severe mitochondrial damage. Flow cytometry analysis further revealed that the total apoptosis rate of CT26 cells increased from 6.37% in the control group to 72.53% in the CD@H-RuO2 + US group (Figure 4E). In conclusion, these results indicate that CD@H-RuO2 has excellent in vitro anti-tumor performance.

(A, B) Measurements of the cytotoxicity of H-RuO2 and CD@H-RuO2 against NIH-3T3. (C, D) Measurements of the cytotoxicity of H-RuO2 and CD@H-RuO2 against CT26 with or without US. (E-H) Apoptosis assay, live/dead and ROS staining, and mitochondrial membrane potential assay of CT26 cells after different treatments. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. (n = 6). ***p < 0.001.

(A) Detection of CRT expression in CT26 cells after different treatments by immunofluorescence staining. (B, C) Measurements of HMGB1 and ATP levels in CT26 cells after different treatments. (D, E) The expression of CD80 and CD86 in DCs after different treatments determined by flow cytometry. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. (n = 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

Furthermore, existing studies have demonstrated that the generation of ROS can effectively trigger ICD [21-23, 66]. During ICD, dying cells release DAMPs, facilitating the engulfment of tumor cells by APCs, thereby promoting tumor-specific immune responses [19, 20, 67]. Based on this mechanism, we employed immunofluorescence staining to detect CRT expressions in CT-26 cells. The strongest CRT signal was observed in the CD@H-RuO2 + US group (Figure 5A). As shown in Figure 5B, the highest HMGB1 level was detected in the CD@H-RuO2+US group, indicating that the synergistic effects of SDT and CDT mediated by CD@H-RuO2 induced the most significant cellular damage. Figure 5C demonstrated that the intracellular ATP level in CT-26 cells treated with CD@H-RuO2 under US irradiation decreased compared to the other groups, suggesting that more ATP was secreted into the extracellular region during the combined SDT and CDT treatment achieved through CD@H-RuO2. Collectively, these results strongly confirmed that CD@H-RuO2 can achieve a robust ICD effect by generating a substantial amount of ROS.

Given that the DAMPs released during the ICD effect induced by CD@H-RuO2 can bind to DCs and activate the adaptive immune response [6, 16], we isolated BMDCs from the tibia and femur of BALB/c mice. Immature DCs were obtained by culturing with IL-4 and GM-CSF. Subsequently, the supernatants of CT-26 cells treated under different conditions (control, US, H-RuO2, CD@H-RuO2, H-RuO2+US, CD@H-RuO2+US) were collected and co-incubated with immature DCs. The cells were then harvested for flow cytometry analysis to evaluate the expression levels of maturation markers. Notably, co-culturing BMDCs with CT-26 cancer cells pre-treated with "CD@H-RuO2 + US" significantly upregulated the expression of maturation markers CD80 and CD86 (Figures 5D, E). This phenomenon indicated that the synergistic effects of SDT and CDT mediated by CD@H-RuO2 enhanced DC maturation and thereby induce a robust immune response.

(A) Schematics show the in vitro anticancer therapy procedures of CD@H-RuO2-mediated combination therapy. (B-E) In vivo, ex vivo imaging and their quantification at different time points after intravenous injection. (F, G) Primary and distant tumor volume of mice in different groups. (H) Body weight of mice after different treatments. (I) Survival of mice in different groups. (J, K) H&E, and TUNEL staining in different groups. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. (n = 5). ***p < 0.001.

To investigate the in vivo antitumor efficacy of CD@H-RuO2, we established a bilateral tumor model in mice and administered the treatment regimen as shown in Figure 6A. First, ICG was used to label CD@H-RuO2 to determine the optimal time window for SDT. Through the animal imaging system, it was observed that the strongest fluorescence signal at the tumor site occurred 24 hours after intravenous injection, indicating this as the optimal timing for US irradiation. This observation confirmed that CD@H-RuO2 effectively accumulated at the tumor site via the EPR effect (Figures 6B-E). Subsequently, the antitumor efficacy of CD@H-RuO2 was evaluated by measuring the volumes of primary and distant tumors, as shown in Figures 6F-G and S18. or both primary and distant tumors, H-RuO2 alone and CD@H-RuO2 alone exhibited weak inhibitory effects on tumor growth. However, with the introduction of US, tumor growth was significantly suppressed, particularly in the CD@H-RuO2 + US group. Notably, the proximal tumor achieved complete eradication after three intravenous injections combined with three ultrasound treatments, while the growth of the distal tumor was also markedly inhibited. These results indicated that the increased production of ROS further amplifies the immune response, thereby achieving the best therapeutic outcome. During the in vivo treatment, there was no significant difference in body weight between the treated groups and normal mice (Figure 6H), demonstrating the good biocompatibility of CD@H-RuO2. Additionally, mice receiving CD@H-RuO2 + US treatment survived for over 50 days (Figure 6I), suggesting that the enhanced SDT mediated by the Z-type heterojunctions of CD@H-RuO2, combined with CDT, induced a robust immunotherapy effect and prolonged the lifespan of mice. Subsequently, histological analysis of the tumor tissues was conducted. ROS staining revealed that the ROS signal in the CD@H-RuO2 + US group was the highest among all groups (Figure S19), further confirming that CD@H-RuO2 successfully accumulated in the tumor tissue and generated a substantial amount of ROS under US irradiation. Furthermore, H&E staining and TUNEL staining showed that the primary tumors in the CD@H-RuO2 + US group exhibited the most severe damage (Figures 6J-K). Consistent results were also obtained in the histological analysis of the distant tumors (Figure S20). These findings collectively demonstrated that CD@H-RuO2-based tumor treatment induced a strong immune response through the generation of large amounts of ROS.

(A) Evaluation of CRT level in tumor tissues after different treatments. (B, C) Measurements of the DC maturation level in the lymph nodes after different treatments. (D-F) T cell activation level in the primary tumor after different treatments including Control, US, H-RuO2, CD@H-RuO2, H-RuO2 + US, and CD@H-RuO2 + US. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. (n = 3). *p < 0.05 and ***p < 0.001.

Next, we conducted a comprehensive immunological analysis to elucidate the underlying mechanism of the potent antitumor effect induced by CD@H-RuO2. Based on the results of in vitro cell experiments, the combination of SDT and CDT mediated by CD@H-RuO2 effectively triggered ICD within tumor cells, promoting the release of DAMPs and further enhancing the maturation of DCs. Firstly, the expression of CRT in tumor tissues was evaluated by immunofluorescence staining. As shown in Figure 7A, tumor tissues from the CD@H-RuO2 + US group exhibited markedly stronger CRT expression compared to other groups. We further evaluated two additional ICD markers—HMGB1 and ATP—using ELISA and an ATP assay kit, respectively. Consistent with the CRT results, levels of both HMGB1 and ATP were significantly elevated in the CD@H-RuO2 + US group relative to other treatments (Figure S21), further confirming the significant induction of ICD by CD@H-RuO2 + US. The release of tumor antigens is known to promote DC maturation, which supports the activation of antitumor T cells and adaptive immunity. Therefore, we analyzed immune cell populations in tumor-draining lymph nodes, spleens, and tumor tissues from each group via flow cytometry. Figures 7B, C showed a pronounced increase in the proportion of mature DCs within the tumor-draining lymph nodes of the CD@H-RuO2 + US group, confirming the treatment's role in driving DC maturation. As a critical component of the immune response, mature DCs can present tumor antigens to T lymphocytes, promoting their proliferation and activation, and ultimately triggering anti-tumor immune killing effects [18]. As expected, after CD@H-RuO2 + US treatment, the percentages of CD8+CD3+ T cells and CD4+CD3+ T cells in the spleens of mice increased significantly from 5.93% to 23.1% and from 5.96% to 33.5%, respectively, compared to the control group (Figure S22). Subsequently, we evaluated the activation of T cells in tumor tissues. Compared with other groups, the expression levels of CD8+CD3+ T cells and CD4+CD3+ T cells in both primary and distant tumors after CD@H-RuO2 + US treatment were markedly enhanced (Figures 7D-F and S23). Furthermore, the "CD@H-RuO2+US" treatment also significantly reduced the proportion of regulatory T cells (Tregs) in the primary tumor (Figure S24). These results strongly indicate that the construction of heterojunctions enabled cascade amplification of ROS generation, thereby activating the antitumor immune response.

Finally, we evaluated the biosafety of the CD@H-RuO2 + US treatment. The major organs of mice subjected to different treatments were analyzed by H&E staining. The results showed no significant differences compared with the control group, and no obvious damage was observed (Figure S25). blood biochemical analysis (Figure S26A) and hematological parameters (Figure S26B) indicated that all blood indicators of the mice remained within the normal physiological range after treatment. In addition, hemolysis assays confirmed outstanding blood compatibility of the material, with a hemolysis rate below 5% even at a high concentration of 400 μg/mL (Figure S27). We further investigated the in vivo biodistribution and excretion pathways of the CD@H-RuO2 nanoparticles to clarify its metabolic behavior in the body. As shown in Figure S28A, 24 hours after intravenous injection, the CD@H-RuO2 mainly accumulated in the liver, spleen and tumor, which was attributed to the capture by the reticuloendothelial system. Over time, by the 14th day after injection, the Ru signal in these organs and tumor tissues significantly decreased, indicating that CD@H-RuO2 was almost completely cleared. To determine the excretion pathways, the Ru signal levels in urine and feces were also quantified. Over time, the Ru signals in feces and urine gradually decreased to almost undetectable levels, indicating that CD@H-RuO2 was mainly cleared from the mice through the hepatic and renal excretion pathways (Figure S28B). These findings collectively confirm the excellent biocompatibility and biosafety of CD@H-RuO2.

Conclusions

In summary, we report for the synthesis of H-RuO2 using Cu2O nanospheres as sacrificial templates to achieve efficient SDT and CDT. It is expected that the catalytic activity of H-RuO2 nanospheres will be superior to that of solid nanoparticles or nanosheets, which can be attributed to their larger specific surface area and more catalytic active sites. By using CDs as the auxiliary sonosensitizers, we prepared CD@H-RuO2 heterojunction nanozymes, which exhibited augmented sonodynamic and multienzyme-mimic activities due to the improved electron hole separation kinetics. The heterojunction construction, along with GSH depletion and hypoxia relief, led to a cascade amplification of antitumor immune response via CD@H-RuO2 nanozymes, ultimately triggering a robust ICD. The combination of CD@H-RuO2-mediated SDT and CDT co-amplified immunotherapy has displayed significant antitumor effects, resulting in the eradication of primary tumors and the inhibition of distant tumor growth.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary methods, figures and table.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Research Projects of Anhui Medical University (No. 2022xkj173), the Health Research Project of Anhui Province (No. AHWJ2023BAc10039), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22278262), and the Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by CAST (No. 2023QNRC001).

Author contributions

Ming Cao: Investigation, Methodology. Yanwei Liu: Formal analysis, Investigation. Zhenlin Zhang: Investigation. Jinming Cai: Formal analysis. Dengyu Pan: Project administration. Bijiang Geng: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Yunsheng Cheng: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. De Ruysscher D, Niedermann G, Burnet NG. et al. Radiotherapy toxicity. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:13

2. Ngwa W, Irabor OC, Schoenfeld JD. et al. Using immunotherapy to boost the abscopal effect. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18:313-322

3. Xu J, Lv J, Zhuang Q. et al. A general strategy towards personalized nanovaccines based on fluoropolymers for post-surgical cancer immunotherapy. Nat Nanotechnol. 2020;15:1043-1052

4. Johnstone TC, Suntharalingam K, Lippard SJ. The Next Generation of Platinum Drugs: Targeted Pt (II) Agents, Nanoparticle Delivery, and Pt(IV) Prodrugs. Chem Rev. 2016;116:3436-3486

5. Xie D, Yan X, Shang W. et al. Organic Radiosensitizer with Aggregation-Induced Emission Characteristics for Tumor Ablation through Synergistic Apoptosis and Immunogenic Cell Death. ACS Nano. 2025;19:14972-14986

6. Sun X, Zhou X, Shi X. et al. Strategies for the development of metal immunotherapies. Nat Biomed Eng. 2024;8:1073-1091

7. Tan M, Cao G, Wang R. et al. Metal-ion-chelating phenylalanine nanostructures reverse immune dysfunction and sensitize breast tumour to immune checkpoint blockade. Nat Nanotechnol. 2024;19:1903-1913

8. Sun X, Zhang Y, Li J. et al. Amplifying STING activation by cyclic dinucleotide-manganese particles for local and systemic cancer metalloimmunotherapy. Nat Nanotechnol. 2021;16:1260-1270

9. Wei Z, Zhang X, Yong T. et al. Boosting anti-PD-1 therapy with metformin-loaded macrophage-derived microparticles. Nat Commun. 2021;12:440

10. Feng W, Han X, Hu H. et al. 2D vanadium carbide MXenzyme to alleviate ROS-mediated inflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Commun. 2021;12:2203

11. Guo Y, Wang SZ, Zhang X. et al. In situ generation of micrometer-sized tumor cell-derived vesicles as autologous cancer vaccines for boosting systemic immune responses. Nat Commun. 2022;13:6534

12. Wang S, Wang Z, Li Z. et al. Amelioration of systemic antitumor immune responses in cocktail therapy by immunomodulatory nanozymes. Sci Adv. 2022;8:eabn3883

13. Jana D, He B, Chen Y. et al. A Defect-Engineered Nanozyme for Targeted NIR-II Photothermal Immunotherapy of Cancer. Adv Mater. 2022;36:2206401

14. Chang M, Hou Z, Wang M. et al. Recent Advances in Hyperthermia Therapy-Based Synergistic Immunotherapy. Adv Mater. 2021;33:2004788

15. Li H, Yang X, Wang Z. et al. A Near-Infrared-II Fluorescent Nanocatalyst for Enhanced CAR T Cell Therapy against Solid Tumor by Immune Reprogramming. ACS Nano. 2023;17:11749-11763

16. Li L, Yang Z, Chen X. Recent Advances in Stimuli-Responsive Platforms for Cancer Immunotherapy. Acc Chem Res. 2020;53:2044-2054

17. Reynders K, Illidge T, Siva S. et al. The abscopal effect of local radiotherapy: using immunotherapy to make a rare event clinically relevant. Cancer Treat Rev. 2015;41:503-510

18. Yu N, Ding M, Wang F. et al. Near-infrared photoactivatable semiconducting polymer nanocomplexes with bispecific metabolism interventions for enhanced cancer immunotherapy. Nano Today. 2022;46:101600

19. Long X, Wang H, Yan J. et al. Tailor-Made Autophagy Cascade Amplification Polymeric Nanoparticles for Enhanced Tumor Immunotherapy. Small. 2023;19:2207898

20. Qi J, Jia S, Kang X. et al. Semiconducting Polymer Nanoparticles with Surface-Mimicking Protein Secondary Structure as Lysosome-Targeting Chimaeras for Self-Synergistic Cancer Immunotherapy. Adv Mater. 2022;34:2203309

21. Li J, Yu X, Jiang Y. et al. Second Near-Infrared Photothermal Semiconducting Polymer Nanoadjuvant for Enhanced Cancer Immunotherapy. Adv Mater. 2021;33:2003458

22. Zhang Z, Yue YX, Li Q. et al. Design of Calixarene-Based ICD Inducer for Efficient Cancer Immunotherapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2023;33:2213967

23. Zheng RR, Zhao LP, Huang CY. et al. Paraptosis Inducer to Effectively Trigger Immunogenic Cell Death for Metastatic Tumor Immunotherapy with IDO Inhibition. ACS Nano. 2023;17:9972-9986

24. Gao C, Kwong CHT, Wang Q. et al. Conjugation of Macrophage-Mimetic Microalgae and Liposome for Antitumor Sonodynamic Immunotherapy via Hypoxia Alleviation and Autophagy Inhibition. ACS Nano. 2023;17:4034-4049

25. Lei H, Kim JH, Son S. et al. Immunosonodynamic Therapy Designed with Activatable Sonosensitizer and Immune Stimulant Imiquimod. ACS Nano. 2022;16:10979-10993

26. Li C, Gao Y, Wang Y. et al. Bifunctional Nano-Assembly of Iridium(III) Phthalocyanine Complex Encapsulated with BSA: Hypoxia-relieving/Sonosensitizing Effects and their Immunogenic Sonodynamic Therapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2022;33:2210348

27. Li Y, Xie J, Um W. et al. Sono/Photodynamic Nanomedicine-Elicited Cancer Immunotherapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2020;31:2008061

28. Huang L, Li Y, Du Y. et al. Mild photothermal therapy potentiates anti-PD-L1 treatment for immunologically cold tumors via an all-in-one and all-in-control strategy. Nat Commun. 2019;10:4871

29. Nam J, Son S, Park KS. et al. Cancer nanomedicine for combination cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Mater. 2019;4:398-414

30. Wang X, Wu M, Li H. et al. Enhancing Penetration Ability of Semiconducting Polymer Nanoparticles for Sonodynamic Therapy of Large Solid Tumor. Adv Sci. 2022;9:2104125

31. He Y, Liu HS, Yin J, Yoon J. Sonodynamic and chemodynamic therapy based on organic/organometallic sensitizers. Coordin Chem Rev. 2021;429:213610

32. Zhang Y, Zhang X, Yang H. et al. Advanced biotechnology-assisted precise sonodynamic therapy. Chem Soc Rev. 2021;50:11227-11248

33. Son S, Kim JH, Wang X. et al. Multifunctional sonosensitizers in sonodynamic cancer therapy. Chem Soc Rev. 2020;49:3244-3261

34. Xu T, Zhao S, Lin C. et al. Recent advances in nanomaterials for sonodynamic therapy. Nano Res. 2020;13:2898-2908

35. Yi X, Zhou H, Chao Y. et al. Bacteria-triggered tumor-specific thrombosis to enable potent photothermal immunotherapy of cancer. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eaba3546

36. Gong F, Cheng L, Yang N. et al. Preparation of TiH1.924 nanodots by liquid-phase exfoliation for enhanced sonodynamic cancer therapy. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3712

37. Wu J, Sha J, Zhang C. et al. Recent advances in theranostic agents based on natural products for photodynamic and sonodynamic therapy. View. 2020;1:20200090

38. Nguyen Cao TG, Kang JH, Kim W. et al. Engineered extracellular vesicle-based sonotheranostics for dual stimuli-sensitive drug release and photoacoustic imaging-guided chemo-sonodynamic cancer therapy. Theranostics. 2022;12:1247-1266

39. Yang S, Wang X, He P. et al. Graphene Quantum Dots with Pyrrole N and Pyridine N: Superior Reactive Oxygen Species Generation Efficiency for Metal-Free Sonodynamic Tumor Therapy. Small. 2021;17:2004867

40. Geng B, Hu J, Li Y. et al. Near-infrared phosphorescent carbon dots for sonodynamic precision tumor therapy. Nat Commun. 2022;13:5735

41. Zhong X, Wang X, Cheng L. et al. GSH-depleted PtCu3 nanocages for chemodynamic-enhanced sonodynamic cancer therapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2020;30:1907954

42. Wang S, Huang P, Chen X. Hierarchical targeting strategy for enhanced tumor tissue accumulation/retention and cellular internalization. Adv Mater. 2016;28:7340-7364

43. Liu Y, Jiang Y, Zhang M. et al. Modulating hypoxia via nanomaterials chemistry for efficient treatment of solid tumors. Acc Chem Res. 2018;51:2502-2511

44. Sun S, Chen Q, Tang Z. et al. Tumor Microenvironment Stimuli-Responsive Fluorescence Imaging and Synergistic Cancer Therapy by Carbon-Dot-Cu2+ Nanoassemblies. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2020;59:2-10

45. Ma B, Wang S, Liu F. et al. Self-Assembled Copper-Amino Acid Nanoparticles for in Situ Glutathione "AND" H2O2 Sequentially Triggered Chemodynamic Therapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141:849-857

46. Xuan W, Xia Y, Li T. et al. Molecular Self-Assembly of Bioorthogonal Aptamer-Prodrug Conjugate Micelles for Hydrogen Peroxide and pH-Independent Cancer Chemodynamic Therapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2020;142:937-944

47. Fu S, Yang R, Ren J. et al. Catalytically active CoFe2O4 nanoflowers for augmented sonodynamic and chemodynamic combination therapy with elicitation of robust immune response. ACS Nano. 2021;15:11953-11969

48. Wang X, Zhong X, Liu Z, Cheng L. Recent progress of chemodynamic therapy-induced combination cancer therapy. Nano Today. 2020;35:100946

49. Liu J, Zhao X, Nie W. et al. Tumor cell-activated "Sustainable ROS Generator" with homogeneous intratumoral distribution property for improved anti-tumor therapy. Theranostics. 2021;11:379-396

50. Xiong Y, Xiao C, Li Z, Yang X. Engineering nanomedicine for glutathione depletion-augmented cancer therapy. Chem Soc Rev. 2021;50:6013-6041

51. Dai Y, Xu C, Sun X, Chen X. Nanoparticle design strategies for enhanced anticancer therapy by exploiting the tumour microenvironment. Chem Soc Rev. 2017;46:3830-3852

52. Fu LH, Qi C, Hu YR. et al. Glucose Oxidase-Instructed Multimodal Synergistic Cancer Therapy. Adv Mater. 2019;31:1808325

53. Xu B, Cui Y, Wang W. et al. Immunomodulation-enhanced nanozyme-based tumor catalytic therapy. Adv Mater. 2020;32:2003563

54. Wang D, Wu H, Wang C. et al. Self-Assembled Single-Site Nanozyme for Tumor-Specific Amplified Cascade Enzymatic Therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2021;60:3001-3007

55. Chen Y, Wang P, Hao H. et al. Thermal Atomization of Platinum Nanoparticles into Single Atoms: An Effective Strategy for Engineering High-Performance Nanozymes. J Am Chem Soc. 2021;143:18643-18651

56. Cai J, Shen Q, Wu Y. et al. Defect Engineering of Biodegradable Sulfide Nanocage Sonozyme Systems Enables Robust Immunotherapy Against Metastatic Cancers. Adv Funct Mater. 2024;34:2411064

57. Geng B, Hu J, He X. et al. Single Atom Catalysts Remodel Tumor Microenvironment for Augmented Sonodynamic Immunotherapy. Adv Mater. 2024;36:2313670

58. Yan L, Chang L, Tian Y. et al. Graphene Quantum Dot Sensitized Heterojunctions Induce Tumor-Specific Cuproptosis to Boost Sonodynamic and Chemodynamic Enhanced Cancer Immunotherapy. Adv Sci. 2024;12:2410606

59. Wang Y, Yan T, Cai J. et al. A heterojunction-engineering nanodrug with tumor microenvironment responsiveness for tumor-specific cuproptosis and chemotherapy amplified sono-immunotherapy. Biomaterials. 2025;321:123319

60. Sun SC, Jiang H, Chen ZY. et al. Bifunctional WC-Supported RuO2 Nanoparticles for Robust Water Splitting in Acidic Media. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2022;61:e202202519

61. Chen S, Huang H, Jiang P. et al. Mn-Doped RuO2 Nanocrystals as Highly Active Electrocatalysts for Enhanced Oxygen Evolution in Acidic Media. ACS Catalysis. 2019;10:1152-1160

62. Tang R, Yuan X, Jia Z. et al. Ruthenium Dioxide Nanoparticles Treat Alzheimer's Disease by Inhibiting Oxidative Stress and Alleviating Neuroinflammation. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2023;6:11661-11678

63. Chen G, Liu P, Liao Z. et al. Zinc-Mediated Template Synthesis of Fe-N-C Electrocatalysts with Densely Accessible Fe-Nx Active Sites for Efficient Oxygen Reduction. Adv Mater. 2020;32:1907399

64. Niu H, Tu X, Zhang S. et al. Engineered core-shell SiO2@Ti3C2Tx composites: Towards ultra-thin electromagnetic wave absorption materials. Chem Eng J. 2022;446:137260

65. Tang J, Hu J, Bai X. et al. Near-Infrared Carbon Dots With Antibacterial and Osteogenic Activities for Sonodynamic Therapy of Infected Bone Defects. Small. 2024;20:2404900

66. Liu XZ, Wen ZJ, Li YM. et al. Bioengineered Bacterial Membrane Vesicles with Multifunctional Nanoparticles as a Versatile Platform for Cancer Immunotherapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2023;15:3744-3759

67. Zhan M, Wang F, Liu Y. et al. Dual-Cascade Activatable Nanopotentiators Reshaping Adenosine Metabolism for Sono-Chemodynamic-Immunotherapy of Deep Tumors. Adv Sci. 2023;10:2207200

68. Qiao QQ, Liu ZR, Hu F. et al. A Novel Ce-Mn Heterojunction-Based Multi-Enzymatic Nanozyme with Cancer-Specific Enzymatic Activity and Photothermal Capacity for Efficient Tumor Combination Therapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2025;35:2414837

69. Wang ZD, Liu JC, Feng M. et al. ROS-activated selective fluorescence imaging of cancer cells via the typical LDH-based nanozyme. Chem Eng J. 2023;470:144020

Author contact

![]() Corresponding authors: E-mail addresses: bjgeng1992edu.cn (B. Geng), chengyunshengedu.cn (Y. Cheng).

Corresponding authors: E-mail addresses: bjgeng1992edu.cn (B. Geng), chengyunshengedu.cn (Y. Cheng).

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact