13.3

Impact Factor

Theranostics 2026; 16(5):2598-2626. doi:10.7150/thno.122864 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Endothelial KSR2 regulated by genetic variation protects against atherosclerosis through AMPKα1 stabilization

1. National Key Laboratory for Innovation and Transformation of Luobing Theory; The Key Laboratory of Cardiovascular Remodeling and Function Research, Chinese Ministry of Education, Chinese National Health Commission and Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences; Department of Cardiology, Qilu Hospital of Shandong University, Jinan, China.

2. Department of Cardiology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Shandong First Medical University, Jinan, China.

3. Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Jinan, China.

Received 2025-7-21; Accepted 2025-11-27; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

Rationale: The single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs11830157 within the scaffold protein kinase suppressor of Ras 2 (KSR2) locus is strongly associated with the incidence of coronary artery disease (CAD), yet its functional role remains undefined. This study aimed to investigate the potential impact of rs11830157 polymorphism on atherosclerosis and to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms.

Methods: Dual-luciferase reporter assays, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA), and CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing techniques were used to investigate the regulatory role of the SNP rs11830157. To assess the role of KSR2 in atherosclerosis, we utilized global KSR2 knockout mice fed a high-fat diet ad libitum, pair-fed global KSR2 and Apoe (Apolipoprotein E) double knockout mice, and mice with endothelial-specific KSR2 overexpression mediated by AAV9-ICAM2.

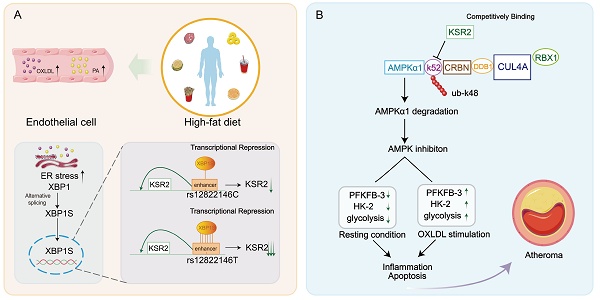

Results: Genetic analyses identified SNP rs12822146, in linkage disequilibrium with rs11830157 and located within an endothelial enhancer, as a regulator of KSR2 expression via differential binding of the transcriptional repressor XBP1s. KSR2 expression was significantly reduced in endothelial cells within atherosclerotic plaques in both humans and mice. Using multiple KSR2 gene-edited mouse models, we demonstrated that endothelial KSR2 protects against atherosclerosis by suppressing inflammation and apoptosis. Mechanistic studies revealed that KSR2 competes with CRBN for binding to the K52 site of AMPKα1, inhibiting CRL4ACRBN E3 ubiquitin ligase complex-mediated K48-linked polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of AMPKα1. The subsequently activated AMPK signaling pathway maintains glycolytic balance in endothelial cells, ultimately exerting anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects.

Conclusions: Our findings provide the first comprehensive molecular explanation of the rs12822146-KSR2-atherosclerosis axis, with important implications for both primary prevention and secondary treatment of CAD.

Keywords: single nucleotide polymorphism, coronary artery disease, endothelial dysfunction, glycolysis, ubiquitin-proteasome system

Introduction

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), a pathological condition manifesting as cardiovascular and cerebrovascular complications including myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke, remains the leading cause of worldwide morbidity and mortality [1]. The vascular endothelium, a continuous cellular layer lining the cardiovascular system, serves as a dynamic interface and plays a critical role as a central hub for numerous regulatory processes within this homeostatic network [2]. Under physiological conditions, this extensive organ maintains systemic tissue and organ homeostasis; yet under pathological conditions, endothelial dysfunction drives both local and systemic features of ASCVD [3]. Despite substantial progress in the study of endothelial dysfunction over the past few decades, our understanding of endothelial dysfunction remains incomplete.

Genetic factors substantially influence susceptibility to coronary artery disease (CAD), and over the past decade, more than 400 independent loci have been identified by genome-wide association studies (GWAS) as contributing to CAD and related clinical outcomes [4-8]. However, linking these GWAS variants to the underlying mechanisms of disease remains a significant challenge. The high-frequency genetic variant rs11830157 (T > G, with G as the risk allele), characterized by a minor allele frequency (MAF) of 29% in general populations, has been consistently identified in multiple Mendelian randomization studies across diverse ethnic cohorts as a risk locus for CAD, with carriers of the risk allele G demonstrating a significantly elevated disease incidence [6, 9]. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs11830157 is situated within the second intron of KSR2 (kinase suppressor of Ras 2), a gene mapped to the human chromosomal locus 12q24. This genomic region has been genetically associated with metabolic disturbances including dyslipidemia and dysglycemia, as well as cardiovascular pathologies encompassing hypertension, coronary artery disease, and myocardial infarction [10-14]. Similar to Kinase Suppressor of Ras 1 (KSR1) [15-17], KSR2 acts as a key scaffold in the Raf/MEK/ERK signaling cascade, controlling both the magnitude and persistence of ERK signaling. The molecular divergence between KSR2 and its paralog KSR1 is functionally substantiated by the identification of a unique interdomain sequence spanning CA2-CA3 motifs in KSR2. This evolutionarily conserved region has been mechanistically demonstrated to engage in direct physical interaction with AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) - the principal regulator of cellular energy balance - thereby potentiating AMPK signaling activation [18, 19]. KSR2-/- mice exhibit decreased AMPK signaling, resulting in defective fatty acid oxidation and triglyceride accumulation, thereby promoting obesity and insulin resistance. Similarly, specific KSR2 mutations in humans with early-onset obesity disrupt ERK pathway activation or hinder AMPK binding [13]. These findings establish KSR2 as a central regulator of systemic metabolism in both mice and humans. Atherosclerosis, the pathological foundation of coronary artery disease, is closely linked to metabolic dysfunction, yet the functional role of KSR2 in this disease process remains unknown.

In this study, we identified that it is not the SNP rs11830157, but rather the allele polymorphism of rs12822146, which is in linkage disequilibrium with rs11830157, that modulates KSR2 expression in endothelial cells via distinct interactions with the transcriptional repressor XBP1s. Using KSR2-modified mice subjected to both ad libitum and pair-feeding regimens, along with adeno-associated virus-mediated endothelial-specific KSR2 overexpression, we demonstrate that endothelial KSR2 confers cell-autonomous atheroprotection. In vitro, we found that KSR2 activates the AMPK signaling pathway through a non-canonical mechanism, maintaining glycolytic balance in endothelial cells and thereby mitigating endothelial inflammation and apoptosis. Mechanistically, KSR2 competitively binds to the K52 site of AMPKα1 with CRBN, inhibiting the CRL4ACRBN E3 ubiquitin ligase complex-mediated K48-linked polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of AMPKα1. Furthermore, endothelial-specific CRBN overexpression or selective activation of endothelial AMPK signalling in vivo established that KSR2 slows plaque progression through a CRBN-AMPK-dependent axis. In addition, endothelial-specific CRBN knockdown similarly reduced inflammation and apoptosis, delaying plaque development in Apoe-/- mice. In summary, we identified a regulatory role of the CAD-associated SNP rs12822146 in controlling endothelial KSR2 expression and uncovered a novel function of the endothelial KSR2-CRL4ACRBN-AMPK axis in vascular inflammation, apoptosis, and atherosclerosis.

Methods

Human Samples

Human coronary artery specimens were obtained from patients undergoing heart transplantation at The First Affiliated Hospital of Shandong First Medical University. The study protocol received approval from the institutional ethics committee (Approval No. S047) and complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was provided by all participants or their legally authorized representatives. All specimens were obtained voluntarily, without coercion, and no organs or tissues were procured from executed prisoners or individuals detained for their political or religious beliefs. Detailed clinical information is provided in Table S1.

Animal Studies

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Shandong University (Approval No. QLYY-2024-266) and conducted in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication No. 86-23, revised 1985). Male mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) environment with controlled conditions, including a temperature of 23°C, 60% relative humidity, and a 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle.

KSR2 knockout (KSR2-/-) mice were generated by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated deletion of exon 3 of the Ksr2 gene (Shanghai Model Organisms Center, Shanghai, China), and bred from Ksr2⁺/⁻ heterozygotes. Apoe-/- mice on a C57BL/6J background were obtained from GemPharmatech (Nanjing, China). Double knockout Apoe-/-Ksr2-/- mice were generated by crossing Apoe-/-Ksr2+/- mice. Mouse genotyping was carried out by PCR using tail-derived genomic DNA (see Table S2 for primers). Throughout the 12-week study, all mice received a high-fat diet (40% fat, 1.25% cholesterol; TP28521, Trophic Animal Feed High-tech Co., Ltd., Nantong, China). Pair-feeding was conducted as previously described [20].

For endothelial-specific KSR2 overexpression, an AAV9 vector carrying the Ksr2 coding sequence under the ICAM2 promoter (BioSune Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) was injected via tail vein into 8-week-old Apoe-/- mice (5 × 1011 vg/mouse). Control mice received AAV9-ICAM2-mock. To activate endothelial AMPK signaling, AAV9-ICAM2-constitutively active AMPKα1 (AAV9-AMPKα1) or control AAV9-mock was injected into Apoe-/- or Apoe-/-Ksr2-/- mice under the same dosing regimen. Endothelial-specific CRBN knockdown was achieved by tail vein injection of AAV9-ICAM2-shCRBN or control AAV9-ICAM2-shNC (BioSune Biotechnology; 5 × 1011 vg/mouse) into 8-week-old Apoe-/- mice. To simultaneously overexpress KSR2 and CRBN in the endothelium, a mixture of AAV9-ICAM2-KSR2 and AAV9-ICAM2-CRBN (BioSune Biotechnology; 5 × 10¹¹ vg of each virus per mouse) was delivered via tail vein injection to 8-week-old Apoe-/- mice. Following viral administration, all treated mice were subsequently fed a high-fat diet for 8 weeks.

Mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg; intraperitoneal injection; once prior to procedures; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Mice were euthanized with an overdose of pentobarbital sodium (150 mg/kg, i.p.) and subsequent cervical dislocation, following institutional and NIH animal care standards.

Cell Culture

HUVECs (CRL-1370) and HEK293T cells (CRL-11268) were obtained from ATCC (Rockville, USA). Primary VSMCs, MAECs, and peritoneal macrophages were isolated from mice as described [21, 22]. Cells were cultured under the following conditions: HUVECs and MAECs in ECM (Sciencell) with 15% FBS, 1% P/S, and 1% growth supplement; HEK293T and macrophages in DMEM (Gibco; 5.5 mM glucose) with 10% FBS and 1% P/S; VSMCs in SMCM (Sciencell; 5.5 mM glucose) with 2% FBS, 1% P/S, and 1% growth supplement. All cells were kept at 37°C with 5% CO₂.

Luciferase Assay

Genomic fragments flanking rs11830157 or rs12822146 (both alleles) were synthesized (Integrated DNA Technologies) and cloned into the pGL4.26 luciferase reporter vector (BioSune Biotechnology, Shanghai, China), upstream of a minimal promoter. Constructs were co-transfected with PRL-TK Renilla luciferase control vector (BioSune) into MAECs, VSMCs, or peritoneal macrophages using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. 11668019) at ~80% confluency. After 48 h, luciferase activity was measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay Kit (MeilunBio, Cat. No. MA0518).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

ChIP was carried out in HUVECs, VSMCs and macrophages employing the SimpleChIP® Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit (#9005, Cell Signaling Technology) in strict accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Crosslinked chromatin was sheared and immunoprecipitated with anti- H3K27ac (Abcam, ab4729), anti-H3K4me1 (Abcam, ab176877), anti-XBP1s (Proteintech, 24168-1-AP), anti-MEIS1 (Cell Signaling Technology, #67260), anti-GATA2 (Proteintech, 11103-1-AP) or control rabbit IgG. Immunoprecipitated DNA was purified and analyzed by qPCR. Primer sequences are listed in Table S3.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

Biotin-labeled DNA probes were prepared using the Biotin-Labeling Kit (GS008, Beyotime), EMSA was conducted using the Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (GS009, Beyotime). Nuclear extracts from HUVECs (5 μg) were incubated with 0.2 μM biotin-labeled probe for 20 minutes at room temperature. For competition assays, a 50-fold molar excess of unlabeled probe was included. For supershift assays, nuclear extracts were pre-incubated with 1 μg anti-XBP1s antibody on ice for 30 min. To assess allele-specific binding at rs12822146, increasing concentrations (10× to 100×) of unlabeled alt probe or 100× non-specific competitor was added with biotin-labeled ref probe. Complexes were resolved on 6% native polyacrylamide gels (0.5× TBE, 100 V, 90 min), blotted onto nylon membranes, and visualized by chemiluminescence. All steps were carried out on ice unless otherwise specified.

CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing

To generate Δrs12822146 HUVECs, two sgRNAs upstream (sgRNA1: TGGCCCCTAGTGAACGGCAG; sgRNA2: TCTTGGACACCATACGACCA) and two downstream (sgRNA3: CTGGTATCCGGTTACAAAGC; sgRNA4: TCTGAAGGTCACTCCTATAT) of the rs12822146 locus were designed using an online tool. Plasmids encoding each sgRNA were transfected into HEK293T cells, followed by puromycin selection 48 h post-transfection. Genomic DNA sequencing confirmed editing activity by the presence of double peaks at all sgRNA target sites.

sgRNA1 and sgRNA3 were selected for lentiviral packaging. Lentivirus was produced and transduced into HUVECs using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After puromycin selection, single-cell clones were expanded, and genomic DNA sequencing confirmed deletion at the rs12822146 locus.

To introduce the homozygous rs12822146 T allele in HUVECs, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated base editing was performed. A sgRNA (sgRNA-A1: GGTGGAGGAACTGAGCGTCAGGG) was designed using CRISPOR and complexed with Cas9 protein to form a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex. A single-stranded DNA donor template (sequence: AAGGCATCCCAGTGTCTACGGCCAAGCAGCTACGTGCCCCTAACTTTTTCAAGCAAGGAGCCTAGGATTGAAAGCAACAATGCAGCCCTGATGCTCAGTTCCTCCACCCTACGTGATCATGATGGCA) containing the C-to-T substitution was co-electroporated with the RNP into cells using the Neon™ Transfection System. After transfection, single-cell clones were isolated and expanded. Genomic DNA was extracted from candidate clones, and the target region was amplified by PCR with primers (F: CGAGGTTCCTGCCAGTTTCT; R: GAGTTCTTTGGGGAGTGGGG). Successful introduction of the homozygous mutation was confirmed by Sanger sequencing and alignment with the wild-type sequence using SnapGene software.

Atherosclerotic Plaque Analysis

After euthanizing the mice with pentobarbital sodium, perfusion was carried out using PBS, followed by tissue fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde. Aortas were dissected, adventitia removed, and stained en face with Oil Red O (O1516, Sigma-Aldrich). Lesion area was quantified as percentage of total aortic surface using ImageJ (NIH, USA).

Aortic root analysis was performed using hearts cryoprotected in 30% sucrose, embedded in OCT (Sakura Finetek), and sectioned into 6-7 µm slices. Staining was carried out with Oil Red O, H&E (G1120, Solarbio), or Masson's trichrome (G1340, Solarbio).

Immunofluorescence staining was performed on aortic root sections using primary antibodies: anti-CD31 (Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA; 1:5000), anti-α-SMA (Abcam, Cambridge, UK; 1:300), anti-CD68 (Abclonal, Wuhan, China; 1:100), anti-KSR2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA; 1:100) followed by fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies and DAPI counterstaining.

Immunohistochemistry involved endogenous peroxidase blocking and incubation with primary antibodies against MOMA-2 (Abcam; 1:200), α-SMA (Abcam; 1:200), VCAM1 (Abcam; 1:50), ICAM1 (Abcam; 1:100), IL-1β (Proteintech; 1:200), TNF-α (Proteintech; 1:400), and KSR2 (Santa Cruz; 1:100), followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and DAB chromogenic detection (ZSGB-Bio, Beijing, China).

All histologically stained sections were imaged utilizing a Pannoramic digital slide scanner (3D HISTECH, Budapest, Hungary). Subsequent quantitative and morphological analyses were performed with Pannoramic Viewer software (3D HISTECH) and ImageJ (NIH, USA).

En Face Aorta Staining

En face immunostaining of mouse aortas was performed as previously described [14]. Briefly, isolated aortas were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies: anti-CD31 (Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA; 1:5000), anti-KSR2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA; 1:100), anti-PFKFB3 (Proteintech; 1:200), and anti-HK2 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK; 1:100). After PBS washes, Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) were applied for 1 h at RT, followed by DAPI nuclear staining (Abcam).

We assessed apoptosis with TMR Red TUNEL staining (Roche, IN) following kit instructions. After 1-h incubation at 37°C in darkness, aortas were DAPI-counterstained and mounted for imaging. Fluorescence imaging employed a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope. The ratio of TUNEL-positive to CD31-positive cells was calculated using ImageJ (NIH) to assess endothelial apoptosis.

Transfection and Infection

Full-length or 373T mutant cDNAs of human KSR2 and CRBN were amplified by PCR and subcloned into pcDNA3.1-Myc vectors. Full-length, truncated, and site-directed mutant constructs of human AMPKα1 and CUL4A were cloned into pcDNA3.1-Flag, and wild-type, K48, or K63 mutant ubiquitin constructs were cloned into pcDNA3.1-HA. Empty pcDNA3.1-Myc, -Flag, or -HA vectors served as controls. Transient transfection of all plasmids was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) following the manufacturer's recommended protocols.

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting XBP1s, KSR2, CUL4A, CRBN, MKRN1, RMND5A, TRIM28, PEDF, FBXo48, RNF44, and AMPKα1 were synthesized by BioSune Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). siRNA sequences are provided in Table S3. Transfections were performed using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen, USA) following the manufacturer's protocol.

THP-1 Adhesion Assay

We labeled THP-1 monocytes with 5 μM Calcein-AM (Beyotime, C2012) and co-cultured them with HUVEC monolayers (37°C, 30 min) for adhesion quantification. After removal of non-adherent cells by PBS washing, adherent THP-1 cells were visualized using fluorescence microscopy (Calcein, green). Quantification was performed in five random fields per well using ImageJ.

Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Protein Extraction

Nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments of HUVECs were separated with a commercial extraction kit (Beyotime P0028) following modified protocols. Extracted proteins were stored at -20 °C until analysis.

Total Protein Extraction and Western Blotting

Protein lysates were isolated from HUVECs, human atherosclerotic plaques, and murine tissues using RIPA buffer (R0010, Solarbio, China) containing protease (CW2200, CWBIO) and phosphatase inhibitors (CW2383, CWBIO). Protein concentrations were measured via BCA assay (P0012, Beyotime, China). Equal protein aliquots (20-30 μg) underwent electrophoretic separation on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and electroblotting onto PVDF membranes (Millipore). Post-blocking (5% milk), membranes were incubated with primary antibodies (4°C, overnight) and HRP-secondaries. Signals were detected by ECL (Millipore WBULS0500) on an Amersham Imager 680RGB (GE Healthcare), with band intensities quantified in ImageJ relative to housekeeping proteins.

RNA Extraction and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from HUVECs, human atherosclerotic plaques, and murine tissues using TRIzol™ Reagent (Invitrogen, 15596018). cDNA synthesis was performed with HiScript III RT SuperMix (Vazyme, R323-01), incorporating genomic DNA removal. Quantitative PCR amplification utilized ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, Q711) on a LightCycler® 96 System (Roche, Switzerland). Relative mRNA expression levels were calculated via the comparative ΔΔCt method normalized to endogenous controls. Primer sequences are listed in Table S2. All experiments were conducted according to the reagent manufacturer's instructions.

Co-Immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

Co-IP assays were conducted to investigate protein-protein interactions in HUVECs, HEK293T cells, human atherosclerotic plaques, and murine tissues. Samples were lysed in native buffer (Beyotime P0013, China) supplemented with protease inhibitors. Following centrifugation to clarify lysates, supernatants were incubated with immunoprecipitation-grade primary antibodies or species-matched IgG controls at 4°C for 1 h. Protein complexes were subsequently captured via overnight incubation with protein A/G magnetic beads (MedChemExpress HY-K0202, USA). Immunoprecipitates underwent stringent washing with PBST (PBS containing 0.5% Tween-20), eluted in SDS loading buffer by boiling, and subjected to immunoblot analysis.

Metabolic Measurements

Glycolytic flux in HUVECs was quantified via extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) measurements using the Seahorse XF96 Analyzer (Agilent Technologies). Cells (1.5 × 10⁴/well) pretreated with 100 μM oxLDL for 24 h were analyzed in XF Base Medium containing 2 mM glutamine (pH 7.4). Sequential injections of glucose (10 mM), oligomycin (1 µM), and 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG, 50 mM) were applied to evaluate basal glycolysis, glycolytic reserve, and glycolytic capacity, respectively.

Lactate production was quantified as an additional indicator of glycolytic activity using the Lactate Assay Kit (BC2230, Solarbio, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

The ATP/ADP ratio in cultured cells was measured with a commercial chemiluminescence assay kit (E-BC-F004, Elabscience) following the manufacturer's protocol. Cell lysates were prepared and reacted with a luciferase-based working solution. Luminescence was recorded (L1) immediately to reflect ATP content. After converting endogenous ADP to ATP in the same sample, total luminescence (L2) was measured. The ATP/ADP ratio was derived as (L2 - L1)/L1.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 9.5 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Data represent mean ± SEM, with biological replicate numbers (N) specified in figure legends; technical replicates were neither averaged nor used as the statistical unit. Exact n values are provided in the corresponding figure legends. Normality was assessed via Shapiro-Wilk testing. Variance homogeneity was determined by F-test (two groups) or Brown-Forsythe test (≥3 groups).

- Two-group comparisons: means were compared with an unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-test when data were normally distributed and variances were equal; otherwise, the Mann-Whitney U test was applied (including all cases where n ≤ 5).

- Multi-group comparisons (> 2 groups): one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test was used when normality and equal variance were satisfied; if either assumption was violated or n ≤ 5 per group, the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's multiple-comparison correction was employed.

- Two-factor designs: two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test.

- For the multiple t-tests (e.g., RT-qPCR results), to ensure the robustness of the analysis results, nonparametric Mann-Whitney U tests (for two groups) were employed for all between-group comparisons. The P values were adjusted using the Bonferroni method to control the family-wise error rate.

Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. Effect sizes for key pairwise comparisons were quantified with Cohen's d (mean difference / pooled SD) and interpreted as small (0.2), medium (0.5), or large (0.8).

Results

Functional SNP rs12822146 regulates endothelial KSR2 expression

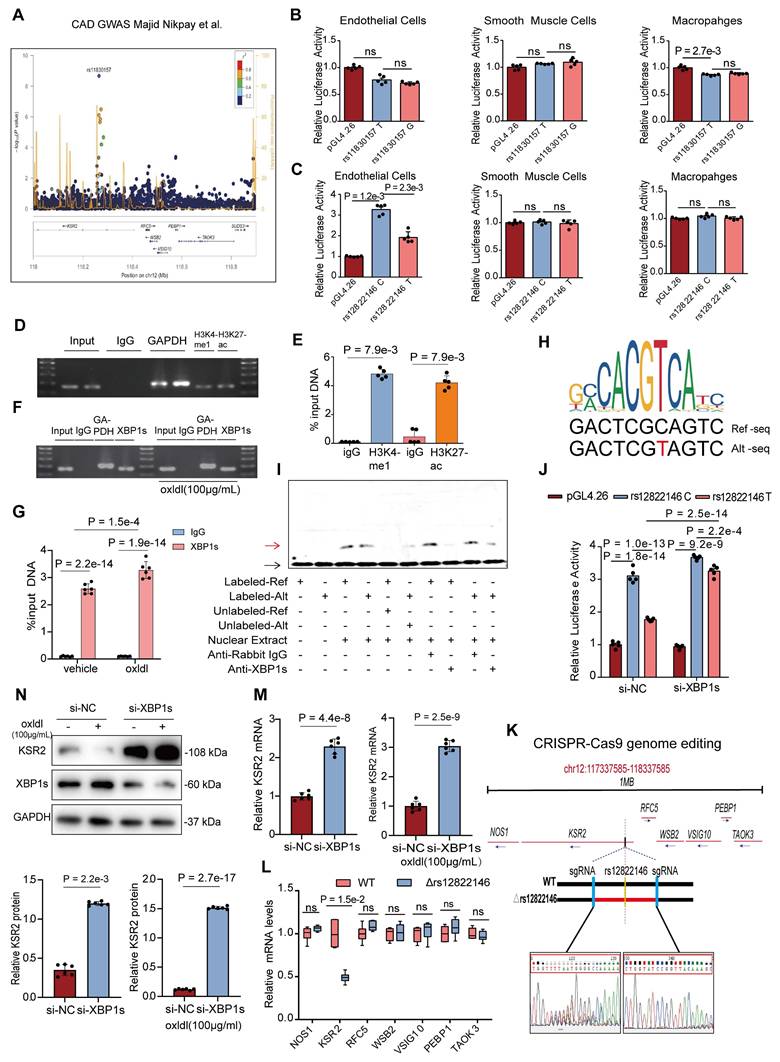

A GWAS meta-analysis of multi-ethnic cohorts (77% European, 13% South Asian, 6% East Asian) demonstrated a recessive-model association between rs11830157 and coronary artery disease risk (OR = 1.12, p = 2.12×10-9) (Figure 1A) [6]. Subsequent analyses revealed no pleiotropic associations between rs11830157 and established cardiovascular risk factors [11]. Corroborating this, a GWAS in type 1 diabetes populations demonstrated persistent association of rs11830157 with CAD incidence following multivariable adjustment for conventional risk factors [9]. Collectively, these findings implicate rs11830157 in CAD pathogenesis through direct vascular mechanisms, independent of traditional risk pathways. While the absence of cis-eQTL associations in vascular tissues (GTEx v8) [23] suggests non-canonical regulatory mechanisms, the genomic context of rs11830157 warrants functional investigation. To determine whether the rs11830157 locus resides within functional genomic elements of vascular wall cells, we cloned 500-1000 bp regions flanking the SNP—containing either the risk or non-risk allele—upstream of a minimal promoter driving firefly luciferase, and assessed its regulatory activity in endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and macrophages. No allele-specific differences in enhancer activity were observed for rs11830157 (Figure 1B). Thus, it is more like a genetic marker than a functional variant. Based on the population distribution in the GWAS study [6], we screened highly linkage disequilibrium SNPs to rs11830157 in the CHB, GIH, and CEU populations on the 1000 Genomes Project website using a threshold of r2 ≥ 0.8 (Table S4), all eight SNPs are located within a ≈18kb region of intron 2 of KSR2 (chromosome 12: 117827344-117845711). Analysis of publicly available ENCODE datasets on the UCSC genome browser [Expanded Encyclopaedias of DNA Elements in the Human and Mouse Genomes] reveals DnaseI, CTCF, H3K4me1(mono-methyl-histone H3 lysine 4), and H3K27ac(acetyl-histone H3 lysine 27) hypersensitivity signals near rs12822146, suggesting this SNP resides in an open chromatin region (Figure S1A). The dual-luciferase assay results indicated that in endothelial cells, rs12822146 exhibited differential activity based on genotype, with the non-risk C allele being significantly more active than the risk T allele (3.27 ± 0.26 vs 1.92 ± 0.27; Cohen's D = 5.09). In contrast, luciferase plasmids containing both allelic sites did not show transcriptional activity in macrophages or smooth muscle cells (Figure 1C). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analyses further revealed significant enrichment of H3K27ac and H3K4me1 at DNA around rs12822146 in human endothelial cells compared to IgG controls (Figure 1D-E), whereas no significant enrichment was observed in macrophages or vascular smooth muscle cells (Figure S1B-C). These findings collectively indicate that rs12822146 resides within an endothelial cell-specific active enhancer region.

Coronary artery disease (CAD) related single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs12822146 allele polymorphism is associated with the expression of the KSR2 gene in endothelial cells. A, Regional association plots illustrating the association between the rs11830157 locus and CAD in the GWAS meta-analysis (OR = 1.12, P = 2.12 × 10⁻⁹). B and C, Luciferase data showing allele-specific activities for rs11830157(T, reference allele; G, alternative allele) and rs12822146(C, reference allele; T, alternative allele) in Mouse Aortic Endothelial Cells (MAECs), primary vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), peritoneal macrophages. n = 5, Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's multiple comparisons test due to small simple sizes. D and E, Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analyses showing enhancer activity in the region surrounding rs12822146 in HUVECs. Pulldown of H3K4me1 (mono-methyl-histone H3 lysine 4), H3K27ac (acetyl-histone H3 lysine 27) was performed to assess the enrichment of chromatin fragments containing rs12822146. n = 5, 2-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney U test due to small simple sizes. F and G, ChIP analyses showing specific binding of XBP1s to the region surrounding rs12822146 in HUVECs, with enhanced enrichment under oxLDL stimulation. n = 6, 2-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test. H, JASPAR database predictions indicating allele-specific binding of the transcription factor XBP1 at the rs12822146 locus. I, Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) demonstrating allele-specific binding of nuclear proteins from endothelial cells to the rs12822146 C and T alleles. Competitive EMSA confirms the specificity of these interactions, while supershift EMSA with XBP1s antibody validates direct binding of XBP1s to both alleles. Black arrow indicates the free biotin-labeled probe; red arrow denotes the protein-probe complex. J, HUVECs were transfected with either CTR siRNA (si-NC) or XBP1s siRNA (si-XBP1s), along with pGL4.26 or luciferase constructs containing rs12822146 alleles, for 48 hours. Luciferase activity was then measured. n = 5, 2-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test. K and L, CRISPR-Cas9-mediated deletion of the genomic region surrounding rs12822146 in HUVECs reduces KSR2 expression. (K) Schematic illustrating the CRISPR-Cas9 editing strategy targeting the rs12822146 locus. (L) Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis showing the expression of protein-coding genes within ±1 Mb of rs12822146 in edited HUVECs. n = 6 per group, genes differential expression were evaluated using a family of 2-tailed Mann-Whitney U tests (multiple t-test framework, one per gene) with Bonferroni adjustment to control the family-wise error rate. M and N, HUVECs were transfected with control siRNA (si-NC) or XBP1s siRNA (si-XBP1s) for 48 h, followed by treatment with or without oxLDL (100 μg/mL) for 24 h. (M) RT-qPCR and (N) western blot showing changes in KSR2 expression. n = 6, except for the left panel of N, which was analyzed using a 2-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney U test due to non-normal distribution, all other results were analyzed using a 2-tailed unpaired Student's t-test. Ref-seq, Reference Sequence; Alt-seq, alternative sequence; ns, not significant.

In silico screening with the PROMO and JASPAR databases predicted that XBP1, MEIS1, and GATA2 differentially bind to the chromatin region encompassing rs12822146. Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays showed that only antibodies against XBP1s—the transcriptionally active spliced isoform of XBP1—selectively enriched rs12822146-flanking fragments over IgG controls in human endothelial cells; this enrichment was further amplified by oxLDL stimulation (Figure 1F-G, Figure S1D-E). No significant binding was detected in macrophages or vascular smooth-muscle cells (Figure S1F-G). In silico motif analysis indicated that XBP1 preferentially recognizes the risk T allele at rs12822146 (Figure 1H). We next experimentally validated this allelic bias in XBP1s binding. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) revealed binding of nuclear proteins from endothelial cells to rs12822146 alleles C and T, with competitive EMSA confirming allele-specific displacement using excess unlabeled probes. Crucially, supershift EMSA results demonstrated a marked reduction in the DNA-protein complex band upon addition of the XBP1s antibody, indicating a direct interaction between nuclear XBP1s and the DNA probe (Figure 1I, Figure S1H). Furthermore, silencing XBP1s expression in HUVECs using si-XBP1s significantly reduced the allele-specific differences in transcriptional activity at rs12822146, as shown by dual-luciferase assays (Figure 1J). Together, these findings indicate that rs12822146 resides within an active endothelial enhancer, and its allelic variants modulate enhancer activity via differential recruitment of XBP1s.

To explore whether the alleles of rs12822146 regulate gene expression in endothelial cells, we used CRISPR-Cas9 to delete a 565bp region encompassing rs12822146 in HUVECs (Figure 1K). Within a 1-Mb region flanking the SNP, seven protein-coding genes were identified: NOS1, KSR2, RFC5, WSB2, VSIG10, PEBP1, and TAOK3. Subsequent quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis revealed that deletion of the rs12822146-containing region significantly reduced KSR2 expression in HUVECs (1 ± 0.17 vs 0.49 ± 0.06, Cohen's D = 4.00), while expression of the other six genes remained unchanged (Figure 1L). Moreover, knockdown of XBP1s led to a marked upregulation of KSR2 in endothelial cells, regardless of the presence of the atherosclerosis-related stimulus oxLDL, suggesting that XBP1s functions as a transcriptional repressor of KSR2 (Figure 1M-N). Since XBP1s is a marker of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress [24], we further validated this using the ER stress inhibitor TUDCA. The results, similar to those observed with si-XBP1s, showed that TUDCA significantly decreased XBP1s expression in endothelial cells and notably increased KSR2 gene expression, both in the presence and absence of oxLDL stimulation (Figure S1I-J). Given that the pathological basis of coronary artery disease is atherosclerosis, we hypothesize that endothelial KSR2 may contribute to the progression of atherosclerosis.

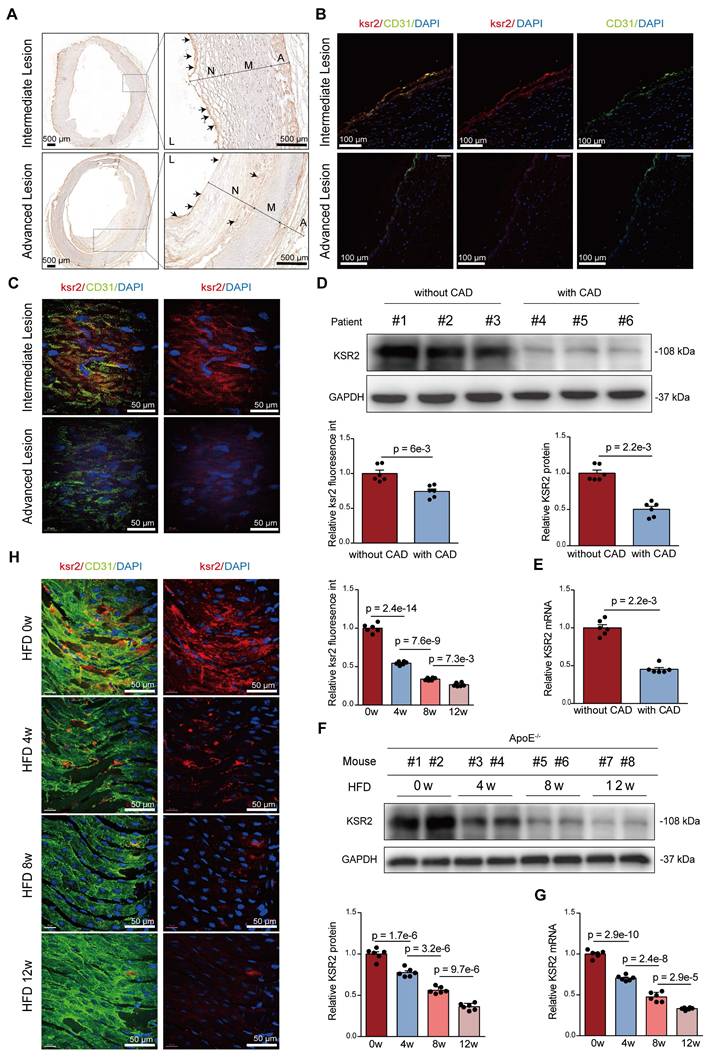

Endothelial KSR2 expression is selectively downregulated during atherosclerosis progression

We next investigated KSR2 expression patterns in atherosclerotic plaques. Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence co-localization analyses of frozen sections from human coronary arteries revealed that KSR2 was predominantly expressed in macrophages and endothelial cells, with minimal expression observed in smooth muscle cells (Figure 2A-B, Figure S2A-B). Notably, endothelial KSR2 expression was significantly decreased in severely atherosclerotic coronary arteries compared to those with mild or moderate lesions, whereas KSR2 levels in smooth muscle cells and macrophages remained largely unchanged. Consistently, en face immunofluorescence staining confirmed the downregulation of endothelial KSR2 in advanced plaques (Figure 2C). In addition, western blot and RT-qPCR analyses demonstrated significantly reduced KSR2 protein and mRNA levels in coronary artery tissues from clinically diagnosed CAD patients compared to non-CAD controls (Figure 2D-E), with baseline characteristics of the patient cohorts summarized in Table S1.

Expression of endothelial KSR2 is reduced in plaques of both mice and humans. A, Immunohistochemical analysis of human coronary artery cryosections from intermediate and advanced lesions showing KSR2 distribution within atherosclerotic plaques. Scale bars = 500 μm. B, Immunofluorescence staining of cryosections from intermediate and advanced coronary lesions showing endothelial KSR2 localization. KSR2 is shown in red, CD31 in green, and nuclei (DAPI) in blue. Scale bars = 100 μm. C, En face immunofluorescence staining of intermediate and advanced coronary lesions showing quantitative changes in endothelial KSR2 expression. KSR2 is shown in red, CD31 in green, and nuclei (DAPI) in blue. Scale bars = 50 μm. n = 6, 2-tailed unpaired Student's t-test. D and E, Western blot (D) and RT-qPCR (E) analyses of KSR2 expression in coronary artery tissues from patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) and non-CAD controls. 2-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney U test due to non-normal distribution. F and G, Western blot (F) and RT-qPCR (G) analyses showing temporal changes in KSR2 expression in aortic tissues from mice fed a high-fat diet (HFD) for 0, 4, 8, and 12 weeks. n = 6, ordinary one-way ANOVA. H, En face immunofluorescence staining of the aortic endothelium showing dynamic changes in KSR2 expression in mice fed a high-fat diet for 0, 4, 8, and 12 weeks. KSR2 is shown in red, CD31 in green, and nuclei (DAPI) in blue. Scale bars = 50 μm. n = 6, ordinary one-way ANOVA. L, lumen; N, neointima; M, media; A, adventitia.

To assess whether similar KSR2 expression patterns occur in murine atherosclerosis, we established a progressive atherosclerosis model in Apoe-/- mice through high-fat diet (HFD) feeding for 0, 4, 8, and 12 weeks. Immunofluorescence co-localization analysis revealed that, consistent with human coronary specimens, KSR2 was primarily localized in macrophages and endothelial cells within murine atherosclerotic plaques, with low expression detected in smooth muscle cells (Figure S2C). Western blot and RT-qPCR results further showed a time-dependent decrease in both KSR2 protein and mRNA levels in the aorta with prolonged HFD feeding (Figure 2F-G). Importantly, primary aortic endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and peritoneal macrophages were isolated from each group of mice. Western blot analysis demonstrated a progressive reduction of KSR2 expression in endothelial cells, while its levels remained relatively unchanged in smooth muscle cells and macrophages (Figure S2D-F). Notably, en face immunofluorescence staining confirmed the gradual decline of endothelial KSR2 expression with increasing plaque severity (Figure 2H). Collectively, these findings suggest that vascular KSR2—particularly within endothelial cells—may play a critical role in the pathogenesis and progression of atherosclerosis.

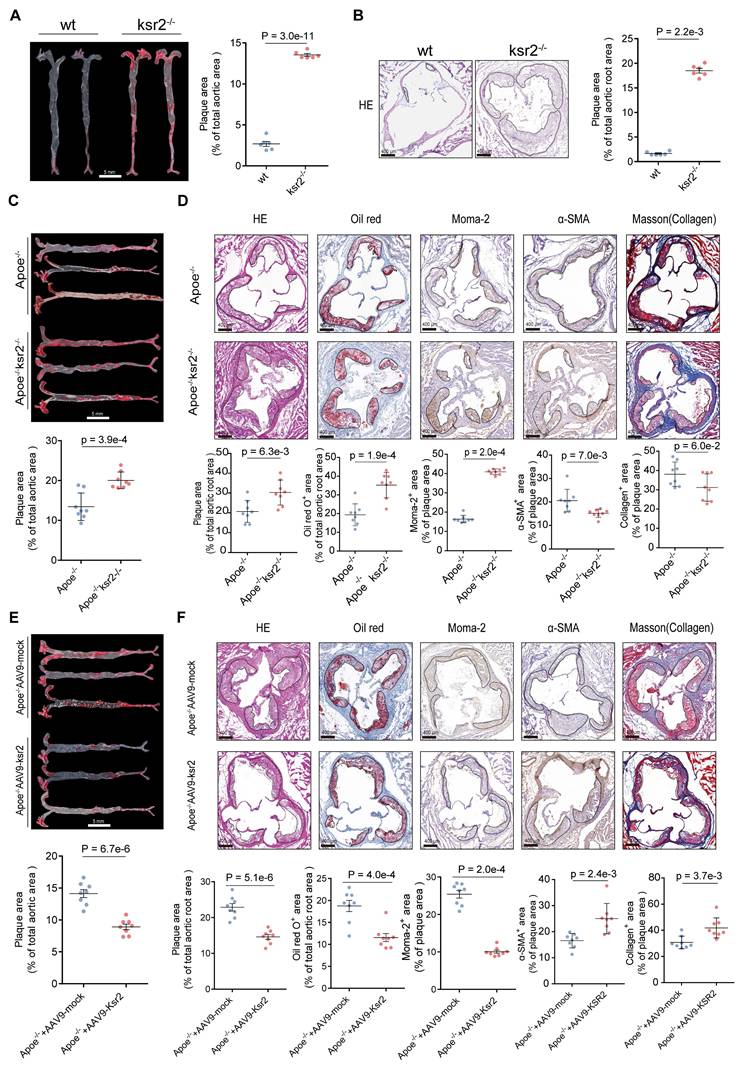

KSR2 mitigates atherosclerosis progression via endothelial cell-autonomous manner

While previous studies using global KSR2 knockout mice primarily focused on obesity and systemic metabolic phenotypes, the vascular implications remained unexplored. To address this, 8-week-old wild-type (WT) and KSR2-/- mice were fed high-fat diet ad libitum for 12 weeks, the knockout strategy and efficiency of KSR2 deletion are shown in Figure S3A-C. Consistent with prior reports, global KSR2 deletion induced weight gain, and systemic metabolic dysregulation (Figure S3D-K). Oil Red O and H&E staining of the aorta revealed markedly increased plaque size in KSR2-/- mice compared with wild-type controls following HFD feeding (Figure 3A-B).

Previous studies have demonstrated that the metabolic disorders observed in KSR2-/- mice are primarily caused by hyperphagia [25]. To further investigate whether KSR2 contributes to atherosclerosis development in a cell-autonomous manner, we generated KSR2 knockout mice on an Apoe-/- background, then controlled the food intake of Apoe-/-KSR2-/- mice to match that of the Apoe-/- mice through pair feeding (PF). After 12 weeks of HFD feeding, no significant differences in serum lipid profiles (triglycerides, total cholesterol, LDL-C, and HDL-C), glucose levels, insulin levels or HOMA-IR index were observed between Apoe-/-KSR2-/- and Apoe-/- mice, except for body weight. Apoe-/-KSR2-/- mice exhibited a slight increase in body weight compared to Apoe-/- mice (Figure S4A-H). Notably, Oil Red O staining of the entire aorta revealed a notable increase in atherosclerotic lesion area in Apoe-/-KSR2-/- mice compared to Apoe-/- mice (Figure 3C). Cross-sectional analysis of the aortic roots further confirmed that KSR2 knockout exacerbated plaque burden, as evidenced by increased lipid deposition, macrophage infiltration, and reduced vascular smooth muscle cell content and collagen accumulation, as assessed by H&E staining, Oil Red O staining, immunohistochemistry for MOMA-2 and α-SMA, and Masson's trichrome staining (Figure 3D). Collectively, these results indicate that KSR2 deficiency accelerates plaque progression independent of serum lipid and glucose levels.

To further investigate the role of endothelial KSR2 in atherosclerosis, we administered AAV9-ICAM2-KSR2 (AAV9-KSR2) via tail vein injection into Apoe-/- mice, resulting in endothelial-specific overexpression of KSR2. In vivo imaging and aortic RT-qPCR confirmed successful KSR2 overexpression in the endothelial cells of the mice (Figure S5A-B). Notably, endothelial-specific overexpression of KSR2 had no significant effects on body weight, blood glucose, lipid profiles, serum insulin or HOMA-IR index (Figure S5C-J). Compared to Apoe-/- + AAV9-ICAM2-mock (AAV9-mock) mice, Apoe-/- + AAV9-KSR2 mice exhibited significantly smaller atherosclerotic plaques, accompanied by reduced lipid deposition and macrophage infiltration, as well as increased vascular smooth muscle cell and collagen content (Figure 3E-F). These findings suggest that endothelial-specific KSR2 overexpression reduces plaque burden and enhances plaque stability, highlighting a protective role for endothelial KSR2 in atherosclerosis progression.

Endothelial KSR2 mitigates atherosclerosis progression. A. Representative en face images of Oil Red O-stained aortas from wild-type and KSR2⁻/⁻ mice fed a high-fat diet ad libitum. Quantification of aortic lesion areas is shown. Scale bar = 5 mm. 2-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney U test due to non-normally distributed data. B. Cross-sectional analysis of aortic roots from wild-type and KSR2⁻/⁻ mice stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Quantification of aortic lesion areas is shown. Scale bar = 400 μm. n = 6, 2-tailed unpaired Student's t-test. C. Representative en face images of Oil Red O-stained aortas from pair-fed Apoe⁻/⁻ and Apoe⁻/⁻KSR2⁻/⁻ mice on a high-fat diet. Quantification of aortic lesion areas is shown. Scale bar = 5 mm. n = 8, 2-tailed unpaired Student's t-test. D. Cross-sectional analysis of aortic roots from Apoe-/- and Apoe-/-KSR2-/- mice stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Oil Red O, MOMA-2 and α-SMA immunohistochemistry (IHC), and Masson's trichrome staining. Scale bar = 400 μm. n = 8. Statistical analyses were performed using a 2-tailed unpaired Student's t-test for all results, except for α-SMA IHC staining, which was analyzed using a 2-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney U-test due to non-normally distributed data. E, Representative en face images of Oil Red O-stained aortas from Apoe-/- + AAV9-mock and Apoe-/- + AAV9-KSR2 mice. Scale bar = 5 mm. n = 8, 2-tailed unpaired Student's t-test. F, Cross-sectional analysis of aortic roots from Apoe-/- + AAV9-mock and Apoe-/- + AAV9-KSR2 mice stained with H&E, Oil Red O, MOMA-2 and α-SMA immunohistochemistry, and Masson's trichrome staining. Scale bar = 400 μm. n = 8, 2-tailed unpaired Student's t-test, except for Masson's trichrome staining, which was analyzed using the 2-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney U test due to non-normally distributed data.

KSR2 mitigates atherosclerosis by inhibiting endothelial cell inflammation and apoptosis

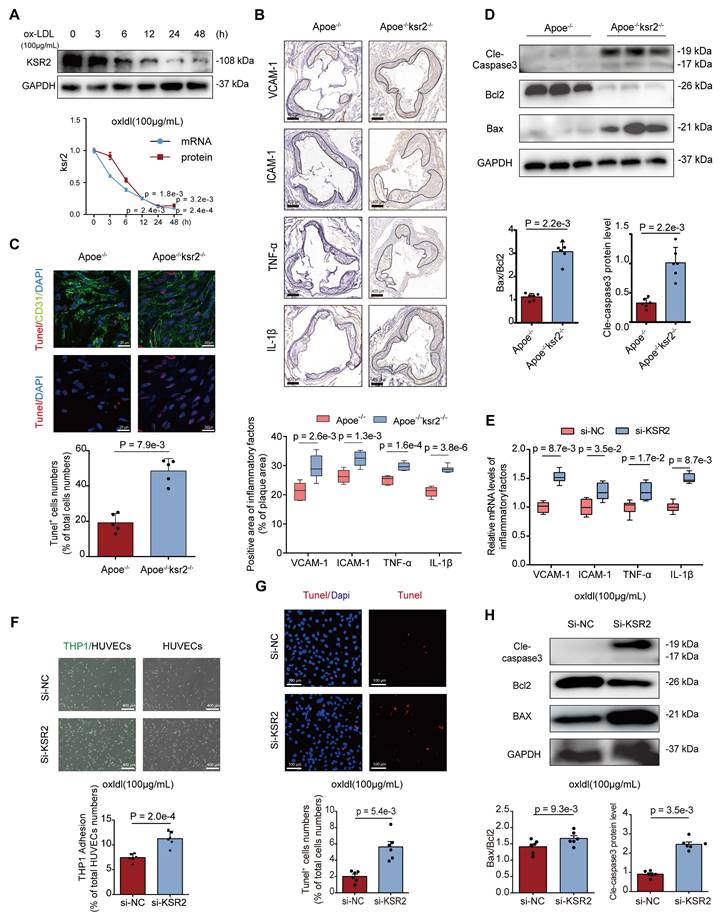

To validate the function of KSR2 in vitro, we initially subjected HUVECs to time-gradient stimulations with oxLDL and palmitic acid (PA). RT-qPCR and WB analysis revealed that both oxLDL and PA treatments significantly reduced the mRNA and protein levels of KSR2 in HUVECs (Figure 4A, Figure S6). Stable KSR2-overexpressing HUVEC lines were generated via lentiviral transduction (Figure S7A). To investigate the underlying mechanisms of KSR2 action, RNA sequencing was performed on KSR2-overexpressing and control HUVECs, identifying 535 upregulated and 444 downregulated genes (fold change ≥1.2; P < 0.05). Gene set enrichment analysis revealed that the differentially expressed genes were significantly enriched in pathways related to metabolism, apoptosis, inflammation, and cell adhesion (Figure S7B-D). Given that endothelial inflammation and apoptosis play pivotal roles in the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis [26], we next investigated the effects of KSR2 on endothelial inflammation and apoptosis both in vivo and in vitro.

To assess the inflammatory response in mouse plaques, we performed immunohistochemical staining analysis. Compared to Apoe-/- mice, Apoe-/-KSR2-/- mice exhibited significantly higher expression levels of ICAM-1, VCAM-1, TNF-α, and IL-1β in atherosclerotic plaques (Figure 4B). To investigate the impact of KSR2 on endothelial cell apoptosis, en face immunofluorescence staining for CD31 and TUNEL was performed on the aortic endothelium. The results revealed a significantly higher proportion of TUNEL-positive cells in the aortic endothelium of Apoe-/-KSR2-/- mice compared to Apoe-/- mice (Figure 4C). Furthermore, western blot analysis showed a marked increase in cleaved-caspase3 and Bax protein levels, while Bcl-2 expression was significantly reduced in Apoe-/-KSR2-/- mice compared to Apoe-/- mice (Figure 4D).

To further investigate the role of KSR2 in endothelial function, we used KSR2-specific siRNA to knock down its expression in HUVECs, with knockdown efficiency confirmed by RT-qPCR (Figure S8). For subsequent experiments, a combination of siRNA-2 and siRNA-3 was used to enhance knockdown efficiency. Under oxLDL stimulation, KSR2 knockdown significantly upregulated the mRNA expression of VCAM1, ICAM1, TNF-α, and IL-1β in HUVECs (Figure 4E). Consistently, THP-1 adhesion assays demonstrated increased monocyte adhesion to HUVECs following KSR2 knockdown (Figure 4F). In parallel, knockdown of KSR2 led to a higher proportion of TUNEL-positive endothelial cells (Figure 4G), accompanied by elevated expression of Bax and cleaved caspase-3, and decreased Bcl-2 protein levels (Figure 4H).

Similarly, immunohistochemistry, TUNEL staining, and WB analyses demonstrated that Apoe-/- + AAV9-KSR2 mice exhibited significantly reduced intra-plaque inflammation and endothelial cell apoptosis compared to Apoe-/- + AAV9-mock controls (Figure S9A-C). Consistent with these findings, in vitro RT-qPCR, THP-1 adhesion assays, TUNEL staining, and WB further confirmed that KSR2 overexpression markedly attenuated inflammation and apoptosis in HUVECs (Figure S9D-G). Taken together, these findings suggest that KSR2 mitigates the progression of atherosclerosis by suppressing endothelial inflammation and apoptosis.

KSR2 suppresses endothelial cell inflammation and apoptosis by maintaining glycolytic balance

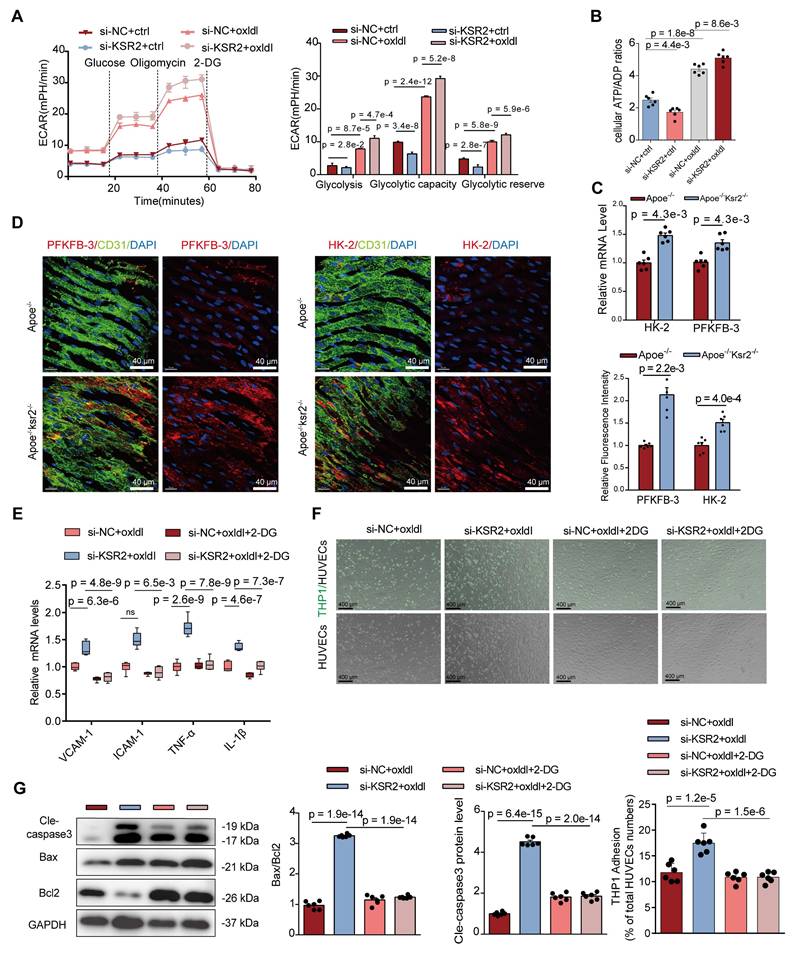

We next sought to further elucidate how KSR2 regulates endothelial inflammation and apoptosis. Transcriptomic analysis revealed that KSR2 significantly influences endothelial cell metabolism, consistent with previous studies identifying KSR2 as a gene closely associated with systemic metabolic regulation. Based on these findings, we hypothesize that KSR2 exerts its anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects by modulating endothelial metabolism. Endothelial metabolism plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of various cardiovascular diseases, with aerobic glycolysis contributing to 75-85% of the total ATP production in endothelial cells [27]. Therefore, we further investigated the relationship between KSR2 and endothelial glycolysis.

First, we assessed the relative expression of glycolysis-related genes in HUVECs. Interestingly, KSR2 overexpression modestly increased the mRNA levels of HK2 and PFKFB3 under resting conditions, yet significantly suppressed the oxLDL-induced upregulation of these genes (Figure S10A). To further investigate glycolytic metabolism, we performed Seahorse Extracellular Flux analysis to measure the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) in HUVECs. Under resting conditions, the results showed a slight increase in glycolysis in KSR2-overexpressing HUVECs compared to controls. However, KSR2 overexpression prominently inhibited the glycolytic increase induced by oxLDL stimulation (Figure S10B). In contrast, when KSR2 expression was inhibited in HUVECs, the ECAR results showed a mild decrease in glycolysis under resting conditions, while oxLDL stimulation led to a further increase in endothelial glycolysis compared to controls (Figure 5A). Given that endothelial cells are largely glycolytic, we next quantified the intracellular ATP/ADP ratio. This functional assessment further corroborates the conclusion that KSR2 is a key regulator of endothelial cell glycolysis (Figure S10C, Figure 5B).

KSR2 deficiency exacerbates atherosclerosis by promoting endothelial inflammation and apoptosis. A, Western blot (WB) and RT-qPCR analyses were performed to assess changes in KSR2 expression in HUVECs after time gradient stimulation with oxLDL (100 μg/mL). Relative values are compared to the 0h control group. n = 5, Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's multiple comparisons test due to small sample sizes. B, Immunohistochemical staining of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, TNF-α, and IL-1β in the aortic roots of Apoe-/- and Apoe-/-KSR2-/- mice. Scale bar = 400 μm. n = 6, 2-tailed unpaired Student's t-test. C, Representative en face TUNEL staining of endothelial cells in the aorta of Apoe-/- and Apoe-/-Ksr2-/- mice. TUNEL-positive cells are shown in red, CD31 in green, and nuclei (DAPI) in blue. Scale bar = 20 μm. n = 5, 2-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney U-test due to small sample sizes. D, Western blot analysis of cleaved caspase-3, Bcl-2, and Bax protein levels in aortic tissues from Apoe-/- and Apoe-/-Ksr2-/- mice. n = 6, 2-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney U-test due to non-normally distributed data. E-H, HUVECs were transfected with control siRNA (si-NC) or KSR2 siRNA (si-KSR2) for 48 h, followed by treatment with oxLDL (100 μg/mL) for 24 h. (E) RT-qPCR was used to measure the mRNA levels of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, TNF-α, and IL-1β. n = 6, 2-tailed Mann-Whitney U tests (multiple t-test framework, one per gene) with Bonferroni adjustment to control the family-wise error rate. (F) THP-1 adhesion assay assessing the adhesive capacity of HUVECs following KSR2 knockdown. Results are presented as the percentage of endothelial cells with adherent THP-1 cells. Scale bar = 400 μm. n = 6, 2-tailed unpaired Student's t-test. (G) TUNEL staining analysis of apoptosis in HUVECs following KSR2 knockdown. Results are presented as the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells. Scale bar = 100 μm. n = 6, 2-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney U test due to non-normally distributed data. (H) WB analysis was used to assess the protein levels of cleaved caspase-3, Bcl-2, and Bax. n = 6, 2-tailed unpaired Student's t-test.

Next, we examined the impact of KSR2 on endothelial cell glycolysis in vivo. In Apoe-/-KSR2-/- mice, the mRNA levels of HK2 and PFKFB3 in the aorta were significantly elevated compared to Apoe-/- mice (Figure 5C). En face staining of the aortic endothelium further revealed increased protein levels of HK2 and PFKFB3 in the Apoe-/-KSR2-/- mice (Figure 5D). In contrast, in Apoe-/- + AAV9-KSR2 mice, the mRNA levels of HK2 and PFKFB3 were significantly reduced compared to Apoe-/- + AAV9-mock mice (Figure S10D), and en face staining also showed corresponding decreases in the protein levels of HK2 and PFKFB3 in the endothelial cells of Apoe-/- + AAV9-KSR2 mice (Figure S10E). Together, these findings strongly suggest that KSR2 plays a crucial role in regulating the balance of endothelial cell glycolysis.

Previous studies have suggested that enhanced glycolysis in endothelial cells can promote the development of atherosclerosis by activating inflammation [28, 29]. Therefore, we investigated whether the protective effect of endothelial KSR2 against atherosclerosis is mediated through glycolysis. To suppress KSR2 expression and glycolytic capacity in HUVECs, we used si-KSR2 and 2-DG, respectively. RT-qPCR results revealed that under oxLDL stimulation, 2-DG effectively counteracted the increase in mRNA levels of VCAM1, ICAM1, IL-1β, and TNF-α induced by si-KSR2 (Figure 5E). Furthermore, THP-1 adhesion assays revealed that under oxLDL stimulation, the inhibition of endothelial cell glycolysis by 2-DG significantly reduced the increased THP-1 adhesion induced by si-KSR2 (Figure 5F). Additionally, western blot analysis demonstrated that 2-DG could restore the elevated protein levels of Bax and cleaved caspase-3, as well as the reduced Bcl-2 levels induced by si-KSR2 (Figure 5G). These results suggest that the protective role of KSR2 in endothelial cells, particularly against inflammation and apoptosis, is mediated through the glycolytic pathway.

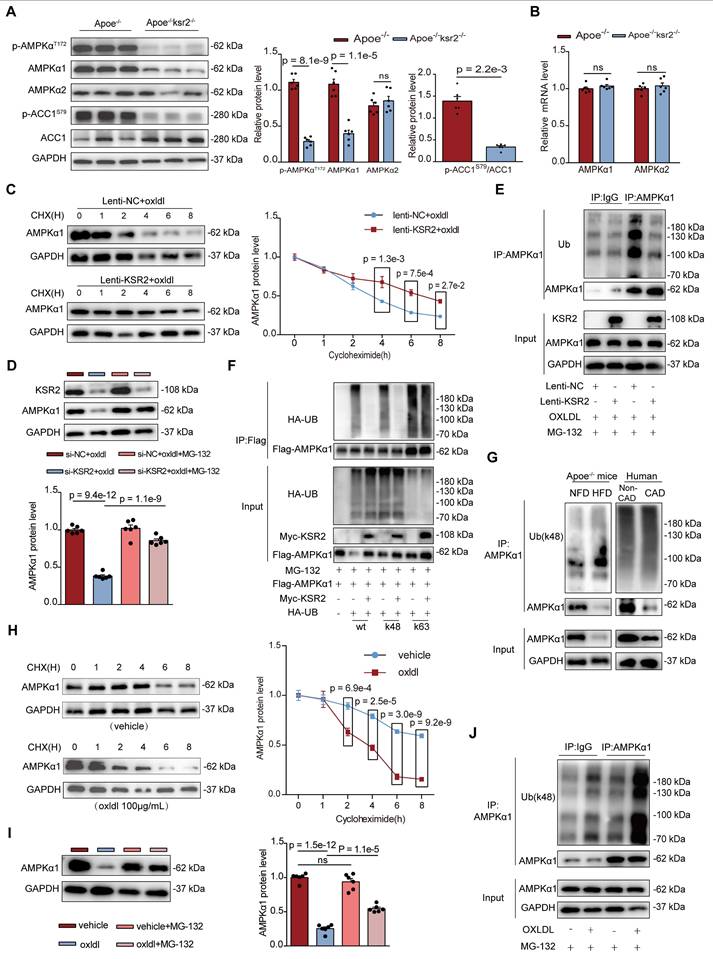

KSR2 inhibits K48-ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation of AMPKα1, activating the AMPK signaling pathway

KSR2 plays a pivotal role in maintaining glycolytic homeostasis in endothelial cells, which prompted us to consider the involvement of the AMPK signaling pathway. As a crucial energy sensor, AMPK monitors cellular energy status and maintains metabolic balance [30, 31]. Its involvement in metabolic regulation is multifaceted, with studies reporting both inhibitory and stimulatory effects on aerobic glycolysis [32, 33]. Previous researches have demonstrated that KSR2 interacts with AMPK, activating the AMPK signaling pathway and modulating downstream metabolic processes [13, 18]. We therefore further investigated whether the protective effects of KSR2 on endothelial cells are mediated through the AMPK signaling pathway.

In Apoe-/-KSR2-/- mice, the protein levels p-AMPKαT172, p-ACC1s79 in the aorta were significantly reduced compared to Apoe-/- mice (p-AMPKαT172, 1.11 ± 0.10 vs 0.29 ± 0.06; cohen's D = 9.94). Surprisingly, the protein level of AMPKα1 was markedly reduced (1.09 ± 0.17 vs 0.40 ± 0.12; cohen's D = 4.69, Figure 6A), while no significant difference in AMPKα1 mRNA expression was observed between the two groups. Moreover, both the mRNA and protein levels of AMPKα2 remained unchanged (Figure 6B). Similarly, compared to Apoe-/- + AAV9-mock mice, there was a significant increase in protein levels of AMPKα1(0.62 ± 0.25 vs 1.00 ± 0.11; Cohen's D = -1.97) and p-AMPKαT172 (0.36 ± 0.09 vs 1.07 ± 0.21; Cohen's D = -4.37), along with elevated levels of p-ACC1s79 in Apoe-/- + AAV9-KSR2 mice (Figure S11A). However, AMPKα2 protein levels and AMPKα1, AMPKα2 mRNA levels remained unchanged (Figure S11B). Western blot analysis revealed that the increase in p-AMPKαT172 was more pronounced than that of total AMPKα1, suggesting that KSR2 not only enhances AMPKα phosphorylation, as previously reported [18, 19, 34], but also directly regulates AMPKα1 protein abundance—a mechanism not described in earlier studies. Therefore, we next sought to elucidate the precise mechanism by which KSR2 regulates AMPKα1 protein abundance. Cycloheximide (CHX) chase assays demonstrated that KSR2 overexpression markedly reduced the degradation rate of AMPKα1 protein (Figure 6C), indicating that KSR2 inhibits AMPKα1 protein turnover.

KSR2 suppresses endothelial inflammation and apoptosis by maintaining glycolytic homeostasis. A and B, HUVECs transfected with si-NC or si-KSR2 for 48 h were treated with oxLDL (100 μg/mL) or control for 24 h. (A) The extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) profile was used to evaluate the glycolytic function of HUVECs. Vertical lines indicate the addition of glucose (10 mM), oligomycin (1 μM), and 2-DG (50 mM). n = 10 for each treatment group, ordinary one-way ANOVA. (B) The cellular ATP/ADP ratio was determined to evaluate energy metabolic shifts in HUVECs. n = 6, ordinary one-way ANOVA. C, RT-qPCR analysis of HK2 and PFKFB3 mRNA levels in aortic tissues from Apoe⁻/⁻ and Apoe⁻/⁻KSR2⁻/⁻ mice. n = 6, 2-tailed Mann-Whitney U tests (multiple t-test framework, one per gene) with Bonferroni adjustment to control the family-wise error rate. D, Representative en face immunofluorescence staining of PFKFB3 and HK-2 in the endothelial cells of the aorta from Apoe-/- and Apoe-/-Ksr2-/- mice. PFKFB3 or HK-2 is shown in red, CD31 in green, and DAPI in blue. Scale bar = 40 μm. n = 6. PFKFB3 results were analyzed using the 2-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney U test due to non-normally distributed data. HK-2 results were analyzed using the 2-tailed unpaired Student's t-test. E, F and G, HUVECs transfected with si-NC or si-KSR2 for 48 h were treated with oxLDL (100 μg/mL) + 2-DG (10 mM) or vehicle for 24 h. (E) RT-qPCR was used to measure the mRNA levels of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, TNF-α, and IL-1β. n = 6, ordinary one-way ANOVA. except for ICAM-1, which was analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's multiple comparisons test due to non-normally distributed data. (F) THP-1 adhesion assay assessing the adhesive capacity of HUVECs. Results are presented as the percentage of endothelial cells with adherent THP-1 cells. Scale bar = 400 μm. n = 6, ordinary one-way ANOVA. (G) WB analysis was performed to measure the protein levels of cleaved caspase-3, Bcl-2, and Bax. n = 6, ordinary one-way ANOVA.

Further mechanistic insights revealed that the proteasome inhibitor MG132 restored AMPKα1 protein levels in KSR2-deficient HUVECs, whereas the autophagy inhibitor 3-MA and lysosome inhibitor chloroquine (CQ) had no effect (Figure 6D, Figure S12A-B). These results indicate that KSR2 prevents AMPKα1 degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasomal pathway. We next investigated the effects of KSR2 on endogenous AMPKα1 ubiquitination in HUVECs. Co-IP assays revealed that KSR2 overexpression significantly reduced the overall ubiquitination levels of AMPKα1 in HUVECs (Figure 6E). To confirm these findings, HEK293T cells were co-transfected with exogenous AMPKα1, KSR2, and ubiquitin plasmids specific for K48, K63, M0, K6, K11, K27, K29 or K33 linkages, the result showed that KSR2 significantly reduced K48-linked ubiquitination of AMPKα1 in HEK293T cells, without affecting any other linkage type (Figure 6F, Figure S13). In summary, these results demonstrate that KSR2 stabilizes AMPKα1 protein levels by suppressing K48-linked ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation, thereby activating the AMPK signaling pathway.

Previous studies on the regulation of the AMPK signaling pathway have primarily focused on mechanisms related to its phosphorylation. In contrast, the ubiquitin-proteasome-mediated degradation of AMPK has been rarely reported. Peng Jiang et al. [35] reported that MG53 mediates K48-linked ubiquitin-proteasome degradation of AMPKα2 in skeletal muscle of type 2 diabetes and obesity models, suppressing AMPK signaling pathway activation. Whether a similar regulatory mechanism exists in atherosclerosis models remains unclear. To investigate this, we performed a series of in vivo and in vitro experiments. Co-IP results revealed a marked increase in K48-linked ubiquitination of endogenous AMPKα1 protein in coronary artery tissues from patients clinically diagnosed with CAD compared to those without CAD. This observation was further validated in HFD-fed Apoe-/- mice (Figure 6G). In HUVECs, CHX chase assays demonstrated that oxLDL treatment accelerated the degradation of AMPKα1 protein (Figure 6H), while MG132, a proteasome inhibitor, partially restored AMPKα1 protein levels under oxLDL stimulation, as confirmed by WB analysis. Notably, MG132 treatment under basal conditions did not further increase AMPKα1 protein levels, suggesting that AMPKα1 degradation is largely independent of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway under basal conditions (Figure 6I). Furthermore, Co-IP assays revealed that oxLDL stimulation markedly increased endogenous K48-linked ubiquitination of AMPKα1 in HUVECs, whereas under basal conditions, K48-linked ubiquitination of AMPKα1 was comparable to IgG controls, consistent with the MG132 results (Figure 6J). In conclusion, our findings provide the evidence that endothelial cell AMPKα1 undergoes a non-canonical ubiquitin-proteasome regulatory mechanism in the context of atherosclerosis. Moreover, KSR2 modulates AMPKα1 activity through this pathway.

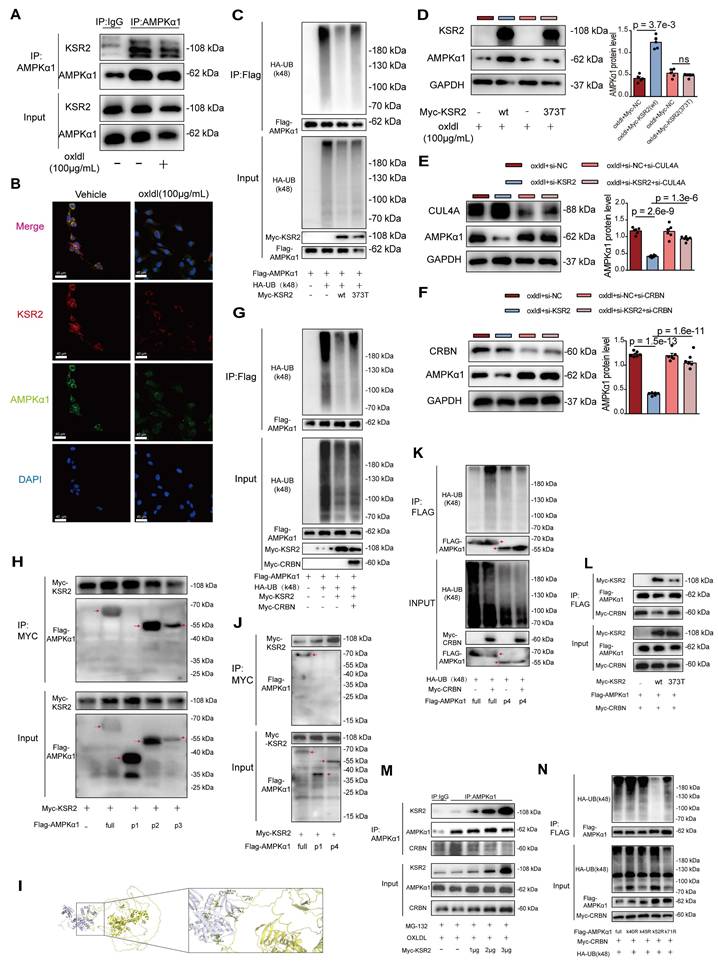

KSR2 competitively binds to the K52 site of AMPKα1, inhibiting the CRL4ACRBN E3 ubiquitin ligase complex-mediated K48 ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of AMPKα1

We next investigated whether the stabilization of AMPKα1 protein by KSR2 is mediated through direct interaction. Co-IP (Figure 7A) and immunofluorescence analyses (Figure 7B) confirmed that KSR2 interacts with AMPKα1 in HUVECs, and this interaction was attenuated upon oxLDL stimulation. Previous studies have identified the amino acid at position 373 (A373) as a critical site for the interaction between KSR2 and AMPKα1 [13]. To further explore this, HUVECs were transfected with a KSR2 mutant plasmid (myc-KSR2 373T). Co-IP results confirmed that the inhibition of K48-linked ubiquitination of AMPKα1 by myc-KSR2 373T was significantly attenuated (Figure 7C). Importantly, Western blot analysis revealed that, compared to the wild-type myc-KSR2 plasmid, overexpression of myc-KSR2 373T resulted in a substantial reduction in the stabilization of AMPKα1 protein levels (Figure 7D). In conclusion, KSR2 stabilizes AMPKα1 protein in endothelial cells through direct interaction, thereby inhibiting its K48-linked ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation and activating the AMPK signaling pathway.

KSR2, as a scaffold protein, lacks intrinsic ubiquitin ligase or deubiquitinase activity. We hypothesized that KSR2 might regulate AMPKα1 ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation via a specific E3 ubiquitin ligase. Seven E3 ubiquitin ligases have been reported to mediate AMPKα1 degradation through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway: MKRN1 [36], RMND5A [37], MAGE-A3/6/TRIM28 [38], PEDF [39], CRL4ACRBN [40], CRL4AFBXo48 [41], and RNF44 [42]. We designed siRNAs targeting the seven E3 ubiquitin ligases mentioned above, western blot analysis showed that si-CRL4A or si-CRBN markedly increased AMPKα1 protein levels in KSR2-depleted HUVECs (Figure 7E-F, Figure S14A-F). Based on these findings, we hypothesize that KSR2 inhibits the E3 ubiquitin ligase CRL4ACRBN-mediated degradation of endothelial cell AMPKα1.

KSR2 inhibits K48-linked ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation of AMPKα1, thereby activating the AMPK signaling pathway. A, Western blot (WB) was used to assess the levels of p-AMPKαT172, AMPKα1, AMPKα2, p-ACC1S79, and ACC1 proteins in the aortic tissue of Apoe-/- and Apoe-/-Ksr2-/- mice. n = 6. All results were analyzed using the 2-tailed unpaired Student's t-test, except for p-ACC1S79/ACC1, which was analyzed using the 2-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney U test due to non-normally distributed data. B, RT-qPCR was used to investigate the mRNA levels of AMPKα1 and AMPKα2 in the aortic tissue of Apoe-/- and Apoe-/-Ksr2-/- mice. n = 6, 2-tailed unpaired Student's t-test. C, Lentiviral stable transfection of HUVECs with lenti-NC or lenti-KSR2 was followed by treatment with oxLDL (100 μg/mL) for 24 h, then cycloheximide (CHX, 50 μg/mL) treatment for 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 h. WB analysis was performed to assess AMPKα1 protein levels. n = 5, 2-way ANOVA. D, HUVECs were transfected with control siRNA (si-NC) or KSR2 siRNA (si-KSR2) for 48 h, followed by pre-treatment with MG132 (10 μM) and subsequent oxLDL (100 μg/mL) stimulation for 24 h. WB analysis was performed to measure AMPKα1 protein levels. n = 6, ordinary one-way ANOVA. E, Lentiviral stable transfection of HUVECs with lenti-NC or lenti-KSR2 was followed by treatment with MG132 (10 μM) and oxLDL (100 μg/mL) for 24 h. Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and immunoblotting were performed to examine the total ubiquitination levels of endogenous AMPKα1 via immunoprecipitation of AMPKα1 or control IgG antibodies. F, HEK293T cells were transfected with myc-KSR2, Flag-AMPKα1, HA-ubiquitin, HA-UB(K48) (lysine 48-specific mutant), HA-UB(K63) (lysine 63-specific mutant), and appropriate control plasmids for 48 h, then treated with MG132 (10 μM) for 24 h. Co-IP and immunoblotting were performed to test the total, K48-linked, and K63-linked ubiquitination of exogenous AMPKα1 via immunoprecipitation of Flag-tagged AMPKα1. G, Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and immunoblotting of endogenous AMPKα1 ubiquitination (K48) levels were performed in the aortic tissue of Apoe-/- mice fed a normal fat diet (NFD) or high-fat diet (HFD) (left), as well as in coronary artery tissues from non-CAD (non-coronary artery disease) and CAD (coronary artery disease) patients. H, HUVECs were treated with oxLDL (100 μg/mL) or vehicle for 24 h, then treated with CHX (50 μg/mL) for 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 h. WB analysis was performed to assess the changes in AMPKα1 protein levels. n = 6, 2-way ANOVA. I, HUVECs were pre-treated with or without MG132 (10 μM), then stimulated with oxLDL (100 μg/mL) for 24 h. WB analysis was performed to measure AMPKα1 protein levels. n = 6, ordinary one-way ANOVA. J, HUVECs were pre-treated with MG132 (10 μM) and then stimulated with oxLDL (100 μg/mL) or vehicle for 24 h. Co-IP and immunoblotting were performed to test the K48-linked ubiquitination levels of endogenous AMPKα1 in HUVECs via immunoprecipitation of AMPKα1 or control IgG antibodies. ns, not significant; UB: ubiquitination; IgG: immunoglobulin G.

KSR2 competitively binds to the K52 site of AMPKα1, inhibiting CRL4ACRBN E3 ubiquitin ligase complex-mediated K48-linked ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of AMPKα1. A, Co-IP and immunoblotting were performed to assess the interaction between endogenous KSR2 and AMPKα1 in HUVECs stimulated with oxLDL (100 μg/mL) for 24 h, using immunoprecipitation of AMPKα1 or control IgG antibodies. B, Immunofluorescence co-localization analysis was used to examine the interaction between endogenous KSR2 and AMPKα1 after oxLDL stimulation. Scale bar = 40 μm. C, HEK293T cells were transfected with myc-KSR2(wt) or myc-KSR2(373T), Flag-AMPKα1, and HA-UB(K48) (lysine 48-specific mutant). Co-IP and immunoblotting were performed to test the K48-linked ubiquitination of exogenous AMPKα1. D, HUVECs were transfected with myc-KSR2(wt) or myc-KSR2(373T) for 48 h, followed by oxLDL (100 μg/mL) treatment for 24 h. WB was used to measure AMPKα1 protein levels. n = 5, Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's multiple comparisons test due to small sample sizes. E and F, HUVECs were transfected with (E) CUL4A siRNA (si-CUL4A) or (F) CRBN siRNA (si-CRBN) along with KSR2 siRNA for 48 h, followed by oxLDL (100 μg/mL) for 24 h. WB was used to assess AMPKα1 protein levels. n = 6, ordinary one-way ANOVA. G. HEK293T cells were transfected with myc-KSR2, Flag-AMPKα1, HA-UB(K48), and myc-CRBN for 48 h. Co-IP and immunoblotting were performed to test K48-linked ubiquitination of exogenous AMPKα1. H. HEK293T cells were transfected with myc-KSR2 and full-length or truncated forms of Flag-AMPKα1(P1 (Δ1-294 aa), P2 (Δ295-396 aa), and P3 (Δ397-574 aa)) for 48 h. Co-IP and immunoblotting were performed to examine the interaction between KSR2 and different AMPKα1 truncates. I, HADDOCK was used to predict the interaction sites and key regions between KSR2 (AF-Q6VAB6-F1) and AMPKα1 (6C9H, 22-559aa). The active residues were predicted using the WHISCY server, and the resulting model was visualized using PyMOL. Note that the AMPKα1 protein structure (6C9H) is incomplete; therefore, the predicted AMPKα1 sites in this model correspond to actual sites (Q13131) with an additional 9 residues. J, HEK293T cells were transfected with myc-KSR2 and full-length or truncated Flag-AMPKα1(P1 (Δ1-294 aa), p4 (Δ1-123 aa)) for 48 h. Co-IP and immunoblotting were used to examine the interaction between KSR2 and AMPKα1 truncates. K, HEK293T cells were transfected with myc-CRBN, HA-UB(K48), and full-length or truncated Flag-AMPKα1 p4 (Δ1-123 aa) for 48 h. Co-IP and immunoblotting were performed to explore the effect of CRBN on K48 ubiquitination of AMPKα1 truncates. L, HEK293T cells were transfected with myc-KSR2 (wt) or myc-KSR2(373T), Flag-AMPKα1, and myc-CRBN for 48 h. Co-IP and immunoblotting were used to investigate the effect of KSR2 binding to AMPKα1 on CRBN interaction. M, HUVECs were transfected with increasing amounts of myc-KSR2 plasmid (0, 1, 2, 3 μg) for 48 h, pre-treated with MG132 (10 μM), and stimulated with oxLDL (100 μg/mL) for 24 h. Co-IP and immunoblotting were performed to detect the interaction between endogenous AMPKα1 and CRBN. N, HEK293T cells were transfected with myc-CRBN, HA-UB(K48), and full-length or mutant Flag-AMPKα1 (K40R, K45R, K52R, K71R) for 48 h. Co-IP and immunoblotting were used to analyze the K48 ubiquitination of exogenous Flag-AMPKα1. ns, not significant.

To further validate this, we utilized the CRBN protein degrader TD165 [43], based on PROTAC technology, and lenalidomide [44], a CRBN protein modulator. Western blot results showed that pre-treatment with TD165 significantly prevented the reduction of AMPKα1 protein levels induced by si-KSR2 in endothelial cells, whereas lenalidomide treatment had no significant effect on AMPKα1 protein levels (Figure S14G-H). These results suggest that the E3 ubiquitin ligase CRL4ACRBN mediates AMPKα1 degradation in endothelial cells via a lenalidomide-independent mechanism, and KSR2 can inhibit this process. More importantly, co-IP results demonstrated that overexpression of CRBN in HEK293T cells significantly restored the K48-linked ubiquitination level of AMPKα1 protein, which had been reduced by KSR2 overexpression (Figure 7G). In summary, these findings indicate that KSR2 inhibits CRL4ACRBN E3 ubiquitin ligase-mediated K48-linked ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of AMPKα1, thereby stabilizing AMPKα1 protein levels.

To identify the specific domain of AMPKα1 involved in its interaction with KSR2 and CRBN, we constructed three truncated AMPKα1 plasmids based on domain positions: P1 (Δ1-294 aa), P2 (Δ295-396 aa), and P3 (Δ397-574 aa). Co-IP results showed that the interaction between AMPKα1 and KSR2 was abolished with the P1 construct, whereas the interactions with P2 and P3 constructs were comparable to that of the full-length plasmid (Figure 7H). These findings indicate that KSR2 interacts with the 1-294 aa region of AMPKα1. To further predict the binding sites between KSR2 and AMPKα1, molecular docking was performed using the HADDOCK web server. The results suggested that the 1-123 aa segment of AMPKα1 forms multiple hydrogen bonds with KSR2 (Figure 7I, Table S5). Based on these predictions, we constructed additional AMPKα1 truncation plasmids: p4 (Δ1-123 aa), Co-IP analysis revealed that, similar to the P1 construct (Δ1-294 aa), the p4 (Δ1-123 aa) fragment exhibited significantly weakened interaction with KSR2, confirming that KSR2 primarily interacts with the 1-123 aa segment of AMPKα1 (Figure 7J). These findings confirm that KSR2 predominantly interacts with the 1-123 aa region of AMPKα1.

Previous studies have demonstrated that CRBN interacts with both the 1-100 aa and 393-473 aa regions of AMPKα1. Furthermore, CRBN competitively binds to the 393-473 aa region of AMPKα1 with the AMPKγ subunit, inhibiting the assembly of the AMPK complex and suppressing its activation [45]. However, the role of CRBN binding to the 1-100 aa region of AMPKα1 remains unclear. Based on our findings and previous research, we hypothesized that the CRL4ACRBN E3 ubiquitin ligase complex mediates K48-linked ubiquitin-proteasome degradation of AMPKα1 via its N-terminal region. Co-IP results demonstrated that the CRL4ACRBN E3 ubiquitin ligase complex significantly increased K48-linked ubiquitination of full-length AMPKα1. However, this effect was abolished in the AMPKα1 P4 construct (Δ1-123 aa) (Figure 7K), supporting our hypothesis. Collectively, these results suggest that both KSR2 and CRBN interact with the N-terminal region of AMPKα1. This led us to investigate whether KSR2 competitively binds AMPKα1, preventing CRL4ACRBN-mediated ubiquitin-proteasome degradation. To explore potential competitive interactions, we co-transfected Myc-CRBN, Flag-AMPKα1, and either KSR2 (wild type, WT) or KSR2 (372T mutant) plasmids into HEK293T cells. Co-IP results showed that overexpression of KSR2 (WT) significantly reduced the interaction between CRBN and AMPKα1, while KSR2 (372T mutant) overexpression had no noticeable effect (Figure 7L). Furthermore, Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) results demonstrated that gradient overexpression of KSR2 (wild type, WT) in HUVECs led to a progressive reduction in the interaction between endogenous CRBN and AMPKα1 proteins (Figure 7M). We observed that while the components of the CRL4CRBN E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, including CUL4A, DDB1, and CRBN, are localized in both the nucleus and cytoplasm under physiological conditions, they predominantly reside in the nucleus [46-48]. In contrast, KSR2 and AMPKα1 proteins are primarily localized in the cytoplasm [13, 49]. To investigate the subcellular localization of CUL4A, DDB1, and CRBN under oxLDL stimulation, we analyzed their distribution in HUVECs. The results demonstrated no significant change in the total protein levels of CUL4A, DDB1, or CRBN upon oxLDL stimulation. However, a pronounced translocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm was observed (Figure S15A). Immunofluorescence further confirmed a marked increase in CRBN cytoplasmic localization under oxLDL stimulation, accompanied by enhanced colocalization with AMPKα1 in the cytoplasm (Figure S15B). These findings suggest that KSR2 competes with CRBN in the cytoplasm for binding to the N-terminal region of AMPKα1, thereby inhibiting CRL4ACRBN-mediated K48-linked ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation and stabilizing AMPKα1 protein levels.

Next, we identified the specific ubiquitination site of AMPKα1. Within the 1-123 aa region, four lysine residues (K40, K45, K52, K71) were identified, then we individually mutated the aforementioned lysine residues. Co-IP results showed that mutation of K52 abolished K48-linked ubiquitination mediated by the CRL4ACRBN E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, while mutations at other lysine residues had no significant effect (Figure 7N). These findings indicate that the CRL4ACRBN E3 ubiquitin ligase complex mediates K48-linked ubiquitin-proteasome degradation of AMPKα1 via K52 in its N-terminal region. Intriguingly, molecular docking using the HADDOCK server predicted hydrogen bond interactions between KSR2 and the K52 residue of AMPKα1. Taken together, these results demonstrate that KSR2 inhibits AMPKα1 K48-linked ubiquitin-proteasome degradation by competitively binding to CRBN at the K52 lysine residue, thereby stabilizing AMPKα1 protein levels.

Endothelial CRBN knockdown delays plaque progression in Apoe⁻/⁻ Mice by inhibiting endothelial inflammation and apoptosis

The above findings suggest that endothelial CRBN is a potential pro-atherogenic molecule, a role not previously characterized. Therefore, we validated this in vivo. Endothelial-specific CRBN knockdown was achieved via tail vein injection of AAV9-ICAM2-shCRBN. Control mice received an equivalent dose of AAV9-ICAM2-shNC. Immunofluorescence staining confirmed that CRBN protein was specifically and efficiently knocked down in endothelial cells (mean fluorescence intensity, 60.03 ± 0.96 vs 10.79 ± 0.98, Cohen's D = 50.76, Figure S16). All groups were subsequently pair-fed a high-fat diet for 8 weeks. Compared to Apoe-/- + shNC mice, Apoe-/- + shCRBN mice exhibited significantly smaller aortic plaques, with reduced macrophage content, whereas no significant differences were observed in smooth muscle cell content or collagen deposition within the plaques between the two groups (Figure S17A-F). Overall, these findings confirm that endothelial CRBN functions as a potential pro-atherogenic molecule.

Next, we investigated whether endothelial CRBN deficiency confers anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects in endothelial cells, similar to those observed with KSR2 overexpression. Immunohistochemistry and aortic RT-qPCR results showed that, compared to Apoe-/- + shNC mice, Apoe-/- + shCRBN mice exhibited significantly reduced expression of inflammatory markers in aortic plaques (Figure S17G-H). En face staining and Western blot results showed a significant reduction in endothelial apoptosis and increased AMPKα1 protein levels in Apoe-/- + AAV9-ICAM2-shCRBN mice compared to Apoe-/- + AAV9-ICAM2- shNC mice (Figure S17I-J). Taken together, these results indicate that endothelial-specific deletion of CRBN markedly alleviates endothelial inflammation and apoptosis, thereby attenuating the progression of atherosclerotic plaque.

Endothelial KSR2 attenuates atherosclerosis progression via CRBN in Apoe-/- Mice

To determine whether endothelial KSR2 restrains atherogenesis via CRBN, Apoe-/- mice received tail-vein co-injection of AAV9-ICAM2-KSR2 (AAV9-KSR2) together with AAV9-ICAM2-CRBN (AAV9-CRBN) or empty vector (AAV9-mock), followed by 8 weeks of high-fat diet. En face Oil Red O staining of aortas, together with Oil Red O and H&E staining of aortic root sections, revealed a significant increase in atherosclerotic lesion size in Apoe-/- + AAV9-KSR2 + AAV9-CRBN mice compared with Apoe-/- + AAV9-KSR2. These results demonstrate that the atheroprotective effect of endothelial KSR2 is mediated through CRBN (Figure S18A-B).

Endothelial KSR2 attenuates atherosclerosis progression by activating endothelial AMPK signaling

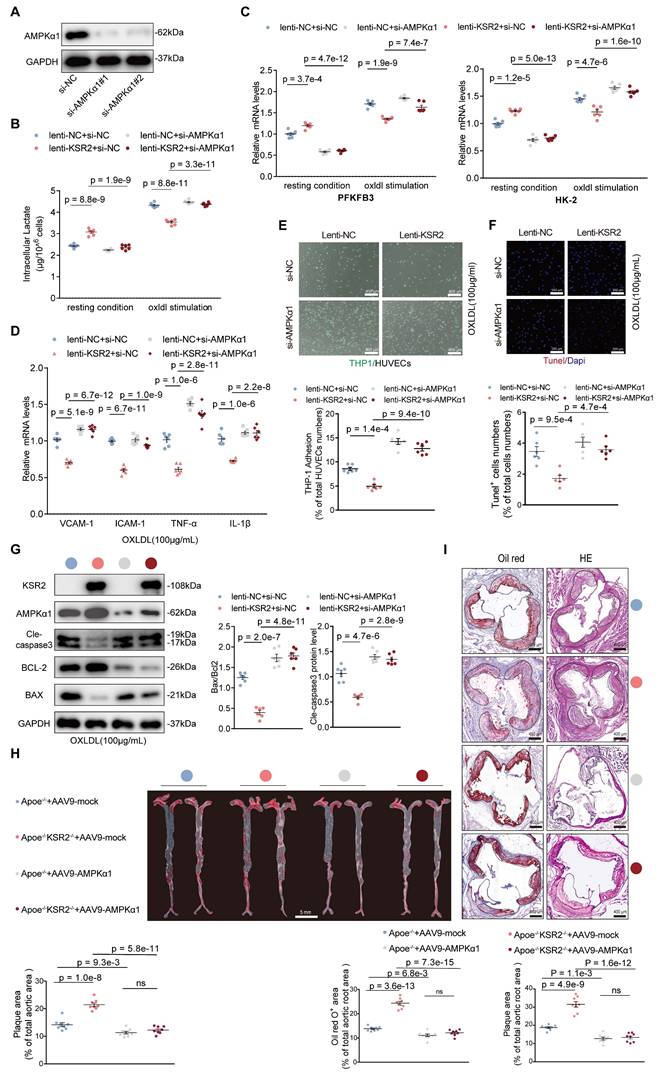

Next, we investigated whether endothelial KSR2 attenuates atherosclerosis via the AMPK signaling pathway both in vivo and in vitro. In vitro experiments, we used two independent siRNAs together to knock down AMPKα1 expression in HUVECs (Figure 8A). Measurements of intracellular lactate, ATP/ADP levels (Figure 8B, Figure S19) and the mRNA levels of PFKFB-3 and HK-2 (Figure 8C) revealed that, under both basal and oxLDL-stimulated conditions, silencing AMPKα1 expression significantly reversed the effects of KSR2 overexpression on glycolysis in HUVECs. Similarly, RT-qPCR analysis demonstrated that the suppression of inflammatory factors, including VCAM-1, ICAM-1, TNF-α, and IL-1β, by KSR2 overexpression was markedly diminished when AMPKα1 was silenced (Figure 8D). Moreover, knockdown of AMPKα1 significantly diminished the inhibitory effect of KSR2 overexpression on THP-1 adhesion in HUVECs (Figure 8E). Furthermore, TUNEL assay (Figure 8F) and WB analysis (Figure 8G) showed that the anti-apoptotic effects of KSR2 on HUVECs were significantly attenuated following AMPKα1 knockdown.

In the in vivo experiments, endothelial AMPK signaling was selectively activated via tail vein injection of AAV9-ICAM2-constitutively active AMPKα1 (AAV9-AMPKα1), while control mice received an equivalent dose of AAV9-ICAM2-mock (AAV9-mock). All groups were pair-fed a high-fat diet for 8 weeks. En face Oil Red O staining, Oil Red O and H&E staining of aortic root cryosections demonstrated that endothelial-specific activation of AMPK signaling significantly attenuated plaque progression in Apoe-/-KSR2-/- mice compared with Apoe-/- controls (Figure 8H-I). Collectively, these in vivo and in vitro findings indicate that KSR2 mitigates endothelial inflammation and apoptosis by activating AMPK signaling, thereby suppressing the progression of atherosclerotic lesions.

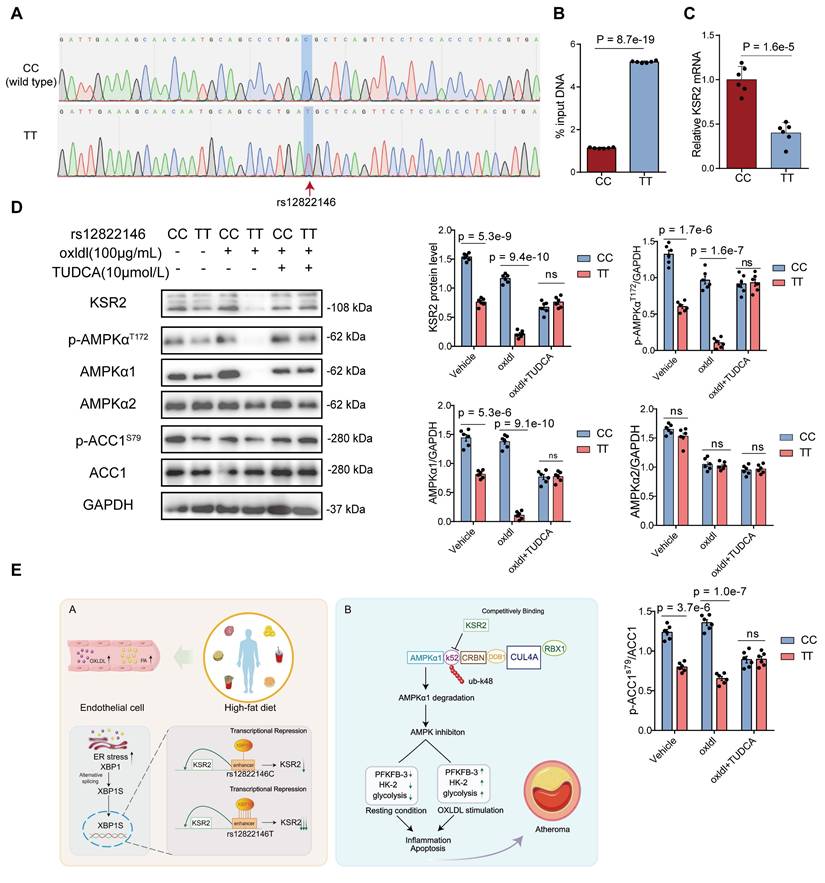

Rs12822146 risk allele impairs AMPK signaling in HUVECs