13.3

Impact Factor

Theranostics 2026; 16(6):2866-2886. doi:10.7150/thno.120935 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Dual targeting of AMRC12 and Malassezia globosa disrupts MYC liquid condensates-driven nuclear pore complex biogenesis in neuroblastoma

1. Department of Pediatric Surgery, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, 1277 Jiefang Avenue, Wuhan 430022, Hubei Province, P. R. China.

2. Department of Pathology, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, 1277 Jiefang Avenue, Wuhan 430022, Hubei Province, P. R. China.

3. Department of Geriatrics, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, 1277 Jiefang Avenue, Wuhan 430022, Hubei Province, P. R. China.

# These authors contributed equally to this work.

Received 2025-7-4; Accepted 2025-12-7; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

Rationale: Neuroblastoma (NB) is a predominant extra-cranial malignancy in childhood, while molecular drivers of its progression and effective treatment strategies have yet to be clarified.

Methods: RNA sequencing was performed to identify transcriptional regulators and corresponding target genes. To explore the biological effects and underlying mechanisms of these regulators, a comprehensive methodology was utilized, encompassing chromatin immunoprecipitation, dual-luciferase reporter assay, qRT-PCR, western blot, alongside gene over-expression and silencing techniques, co-immunoprecipitation, and mass spectrometry. The MTT assay, soft agar colony formation, Matrigel invasion, and nude mouse xenograft models were applied to assess oncogenic properties. Patient survival was analyzed using the log-rank test.

Results: Armadillo repeat containing 12 (ARMC12) was identified as a MYC-interacting modulator within liquid condensates to up-regulate critical nucleoporin-encoding targets (NUP62/NUP93/NUP98), which promoted nuclear pore complex (NPC) biogenesis to facilitate nuclear trafficking of oncogenic effectors, thereby enhancing invasion and metastasis of NB. As a protein within extracellular vesicles of Malassezia globosa colonizing NB tissues, MGL_0381 also facilitated MYC transactivation via physical interaction to accelerate NPC biogenesis and NB progression. Tioconazole (TCZ) and UU-T02 were identified as efficient inhibitors blocking ARMC12-MYC and MGL_0381-MYC interaction, and synergistically reduced NPC number and aggressive features of NB. High ARMC12, MYC, NUP62, NUP93, or NUP98 levels served as markers of unfavorable patient outcomes in clinical cohorts.

Conclusions: These findings collectively demonstrate that dual targeting of AMRC12 and Malassezia globosa disrupts MYC liquid condensates-driven NPC biogenesis during NB progression.

Keywords: neuroblastoma, armadillo repeat containing 12, MYC, Malassezia globosa, nuclear pore complex

Introduction

Neuroblastoma (NB), an extracranial malignancy originating from sympathetic nervous system, is most prevalent in pediatric populations, and presents heterogeneous clinical behavior varying from spontaneous regression to aggressive metastatic dissemination [1]. Despite multimodal therapeutic strategies incorporating surgical resection, cytotoxic chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, over 50% of high-risk NB patients suffer from rapid recurrence, local invasion, or systemic metastasis, culminating in dismal 5-year survival rates below 20% [1, 2]. Therefore, it is urgent to delineate the molecular drivers and develop precision therapeutics targeting aggressive behaviors of NB. Beyond the well-known oncogenic driver MYCN that is amplified in almost 20% of high-risk NB, elevated MYC expression is an independent marker and defines a distinct high-risk subset in approximately 10% of cases [3], while its roles and protein partners in NB progression require systematic interrogation.

Nuclear pore complex (NPC), a critical gateway for nucleocytoplasmic transport, contributes to malignant transformation and tumor progression via facilitating karyopherin β superfamily-mediated transport of macromolecules [4]. Certain proteins (such as β-catenin) interact directly with NPC components for nuclear translocation [5, 6]. Many cancer cells exhibit increase of NPC numbers and addiction on nuclear transport machinery [4]. The NPC is consisted of 30 nucleoporins (NUPs) to form distinct structural modules, including central cylinder, cytoplasmic and nuclear rings, cytoplasmic filaments, and nuclear basket [7]. NPC biogenesis is a highly ordered process involving sequential recruitment of NUP107-160 (early assembly) and NUP93-205 (later assembly) complexes [8]. Some NUP components, such as NUP62, NUP93, and NUP98, are linked to tumorigenesis and aggressiveness [5, 6, 9, 10]. NUP62 is up-regulated in renal clear cell carcinoma, glioma, or adrenocortical carcinoma, and correlated with poor prognosis of patients [11]. As a critical NUP over-expressing in metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma [6], breast cancer [12], and cervical cancer [13], NUP93 facilitates the proliferation and metastasis of cancer cells by mediating nuclear translocation of β-catenin [5, 6]. NUP98, a NUP localizing at both cytoplasmic and nucleoplasmic sides of NPC, contributes to progression of acute myeloid leukemia via recurrent chromosomal translocations [14]. Meanwhile, reducing NPC numbers is sufficient to induce regression of melanoma and colorectal cancer via affecting nuclear transport, gene expression, or DNA damage repair [4]. These findings underscore NPC components as pivotal regulators and therapeutic targets of tumorigenesis. Nonetheless, the contributions of NUPs and regulation of their expression in the context of NB progression remain elusive.

In the current study, through integrating proteomic profiling, chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq), and transcriptome-wide characterization, we discover that armadillo repeat containing 12 (ARMC12) serves as a co-factor of transcription factor MYC to drive the expression of nucleoporin-encoding genes (NUP62, NUP93, and NUP98), leading to elevation in NPC number and nuclear translocation of transcriptional regulators, such as AMRC12 [15], MYC [16], cut like homeobox 1 (CUX1) [17], or E2F transcription factor 1 (E2F1) [18], and invasion or metastatic dissemination of NB cells. In addition, as a protein within extracellular vesicles (EVs) of Malassezia globosa (M. globosa) colonizing NB tissues, MGL_0381 interacts with and facilitates MYC transactivation to drive NPC biogenesis and NB progression. Through molecular docking and affinity purification assays, tioconazole (TCZ) and UU-T02 are identified as efficient inhibitors blocking ARMC12-MYC or MGL_0381-MYC interaction. Administration of both TCZ and UU-T02 exerts synergetic inhibitory effects on NPC biogenesis and aggressiveness of NB, highlighting the biological significance of MGL_0381/MYC and ARMC12/MYC axes in orchestrating NB malignant progression.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and culture

Following acquisition from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD) or European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (ECACC, Salisbury, UK), the employed human cell lines, HEK-293T (CRL-3216), SH-SY5Y (CRL-2266), SK-N-AS (CRL-2137), SK-N-BE(2) (CRL-2271), SH-EP (CVCL_0524), underwent authentication via short tandem repeat profiling. Subsequent functional experiments were conducted within six months after cell thawing. Routine screening for mycoplasma contamination was conducted with the MycoAlert® PLUS Kit (Takara, Japan). Specifically, cells validated to be free of contamination were grown in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO₂, using DMEM or RPMI-1640 medium fortified with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Gaithersburg, MD).

Isolation and quantitative analysis of RNA

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany), which was then reversely transcribed into cDNA with the ProtoScript® II kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). Subsequent quantitative PCR (qPCR) was carried out using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Takara, Japan) and sequence-specific primers (listed in Table S1). The mRNA quantification was calculated by 2 -△△Ct method [16, 18-23].

Western blotting

Following lysis of tissues or cultured cells with RIPA buffer (Promega, Madison, WI), the resulting protein extracts were analyzed by western blotting using established methodologies [16, 18-23] and antibodies specific against ARMC12 (PA5-111006, Thermo Fisher Scientific), MYC (ab32072), NUP62 (ab188413), NUP93 (ab53750), NUP98 (ab124980), CUX1 (ab307821), E2F1 (ab4070), histone H3 (HH3, ab5103), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, ab8245), glutathione S-transferase (GST, ab307273), His-tag (ab18184), hemagglutinin (HA)-tag (ab236632), FLAG-tag (ab125243), or β-actin (ab7291, Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA).

Assay for dual-luciferase reporter activity

Amplicons of human NUP62 (-791/+134), NUP93 (-1000/+197), or NUP98 (-704/+146) promoter regions were generated from genomic DNA with primers detailed in Table S2 and cloned into pGL3-Basic vector (Promega). The MYC-binding motifs were mutagenized using the Q5® system (New England Biolabs) with custom-designed primers (Table S2). For analyzing MYC transactivation, luciferase reporter constructs were generated through ligating oligonucleotide pairs with three typical MYC response elements (Table S2) into pGL4.1 luciferase vector (Promega). The transcriptional activity was measured via LiveCell™ Dual-Luciferase Assay Kit (Biotium, Fremont, CA) and a GloMax® Luminescence Reader (Promega) [16, 18-23].

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

ChIP experiments were conducted using the EZ-ChIP kit (Millipore, Burlington, MA) [16, 18-23], with antibodies targeting MYC (ab32072). For real-time qPCR analysis, immunoprecipitated DNA was amplified using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Takara) and primers listed in Table S1. Isotype IgG served as the negative control for data normalization.

Modulation of gene expression

The coding sequence of human ARMC12 (1104 bp) or MYC (1368 bp) was amplified from NB specimens (Table S2), while their full-length fragments or truncations were inserted into pCMV-3Tag-1A (Addgene, Cambridge, MA), pCMV-HA (Addgene), pGEX-6P-1 (Beyotime Biotechnology, Haimen, China), pET28-A (Addgene) [15, 16], pET28a-mCherry (Genprice Inc., San Jose, CA), pET28a-EGFP (Genprice Inc.), pCMV-N-MYC (Addgene), or CV186 (Genechem Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China). The NLS-mCherry-NES reporter (pDN160) was obtained from Addgene. The Q5® system (New England Biolabs) was utilized to generate mutations at specified sites, using primers provided in Table S2. To generate stable cell lines, short hairpin RNA (shRNA) or small guide RNA (sgRNA) oligonucleotides (Table S3) were first cloned into GV298 (Genechem), dCas9-VPR, or dCas9-BFP-KRAB (Addgene) backbones, which was followed by antibiotic selection using neomycin or puromycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Gene expression restoration

The ARMC12 expression vector was used to transfect tumor cells in order to prevent gene expression affected by MYC knockdown. The Genesilencer reagent (Genlantis, San Diego, CA) was used to transfect shRNAs targeting ARMC12 (Table S3) to rescue MYC over-expression-induced changes in target gene expression. As controls, an empty vector or scramble shRNA (sh-Scb) was used (Table S3).

Lentivirus production

To produce lentivirus, HEK-293T cells were co-transfected with the transfer vector and packaging plasmids psPAX2 and pMD2G (Addgene). Viral supernatants were harvested at 36 and 60 h post-transfection. Following filtration through 0.45 μm low-protein-binding polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore), the lentiviral particles were concentrated by ultracentrifugation (120,000 × g, 2 h, 4 °C) and finally resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 1/100 of the original volume [16, 18-20].

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq)

From aliquots of 1 × 10⁶ cells, total RNA was purified employing the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) for subsequent RNA sequencing. The RNA-seq library was constructed by Wuhan SeqHealth Technology Co., Ltd., in accordance with standard Illumina protocols and sequenced on the HiSeq X Ten platform (Illumina), yielding 100-bp paired-end reads. Subsequent data processing involved quantification of gene-level reads with HTSeq (version 0.6.0) under the union-counting mode, followed by normalization using fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM). The raw and processed data were publicly accessible through the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository under the accession GSE107516.

Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) and mass spectrometry

Following co-IP with specific antibodies for ARMC12 (PA5-111006, Thermo Fisher Scientific), MYC (ab32072), FLAG-tag (ab125243), or HA-tag (ab236632, Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA), the bead-bound protein complexes were eluted. These eluates were then subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) separation and analyzed either by Coomassie blue staining/immunoblotting or by mass spectrometry (Wuhan SpecAlly Life Technology Co., Ltd., China) [16, 18-23].

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC)

The split-Venus system was constructed by inserting ARMC12 (1104 bp) or MYC (1368 bp) cDNA into pBiFC vectors (Addgene) followed by co-transfection into tumor cells with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) for 24 h. Following this, cells were incubated in standard medium at 37 °C with 5% CO₂ for 10 h to allow fluorophore maturation. Venus reconstitution was monitored by confocal microscopy with the following settings: excitation at 488 nm and emission collected between 500-550 nm [16, 18-20].

Immunofluorescence staining

For paraffin-embedded tissues, the sections were subjective to deparaffinization and rehydration, and blocked with 5% normal serum to prevent non-specific binding. Cultured cells were seeded onto coverslips, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, and blocked with 5% milk for 1 h. Following this, samples were subjected to incubation with the respective primary antibodies targeting ARMC12 (PA5-111006, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 1 : 200), MYC (ab32072, Abcam Inc., 1 : 200), nuclear pore complex (mAb414, ab24609, Abcam Inc., 1 : 200), or Lamin A (ab108595, Abcam Inc., 1 : 200) overnight at 4 °C. After washing, samples on coverslips were stained sequentially with secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor® 488 or 594, Cell Signaling Technology Inc. Danvers, MA) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Sigma, St. Louis, MO), prior to image acquisition on a Nikon confocal microscope [16, 18-20].

18S rRNA sequencing

Tissue homogenates in PBS (500 μL) were mechanically lysed via vortex-sonication followed by Proteinase K digestion (2.5 μg/mL; Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 55 °C overnight. DNA was extracted using the DNeasy PowerSoil Pro system (Qiagen), quantified via Qubit BR assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and processed for Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) sequencing (Wuhan SeqHealth Technology Co., Ltd.).

Fungal fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

Fungal colonization was localized using a Cy3-conjugated 18S rRNA probe (Table S1; λex 561 nm/λem 570 nm; Servicebio Tech, China) through FISH. Paraffin-embedded tissue sections (4 μm) underwent sequential blocking with hybridization buffer (37 °C, 30 min), probe hybridization (20 μM in buffer, 37 °C, overnight), and stringent washes. Nuclear counterstaining with DAPI preceded microscopic analysis using a Nikon Eclipse Ti system [24].

M. globosa culture and MalaEx preparation

M. globosa (MYA-4612, ATCC) was cultured on Modified Leeming and Notman agar medium (mLNA, ATCC) plates modified to contain 0.5% Tween 60, 1% glycerol, and 2% olive oil at 32 °C [25]. MalaEx was prepared via continuous ultrafast centrifugation from culture supernatant of M. globosa for 48 h. Briefly, culture supernatants underwent sequential centrifugation (1,200 g × 5 min, 3,000 g × 30 min) with intermediate pellet removal. Clarified samples were sterile-filtered (0.22 μm, Merck, Germany) followed by ultracentrifugation steps (10,000 g × 30 min, 100,000 g × 90 min × 2 cycles) with PBS washing. Final exosome pellets were reconstituted in 100 μl PBS. MalaEx was characterized through morphological analysis and nanoparticle tracking, with subsequent proteomic profiling via liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), which was performed by SpecAlly Life Technology Co., Ltd in Wuhan, China.

Mass spectrometry

Proteomic analysis was performed using a Q Exactive Plus mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled to an EASY-nLC 1200 nanoflow liquid chromatography system. For peptide separation, a C18 analytical column (Acclaim PepMap; 75 μm × 150 mm, 2 μm, 120 Å) was used with a 30-min linear gradient from 0.1% formic acid to 80% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid, at a constant flow rate of 300 nL/min. Data-dependent acquisition (DDA) parameters included: full MS scans [70 K resolution, 3 × 10⁶ automatic gain control (AGC), 20 ms max injection time, m/z 350-1800) followed by top-15 HCD-MS/MS (resolution at 17,500, AGC target of 2 × 105, maximum injection time of 100 ms, and normalized collision energy of 28%) with 1.6 Da isolation window and 35-s dynamic exclusion. Raw files were processed through MaxQuant (v1.6.6) against the UniProt Human database, applying 1% false discovery rate (FDR) thresholds at peptide and protein levels.

Monitoring in vitro phase separation

Recombinant His-tagged proteins were expressed by transforming ARMC12/MYC constructs into BL21 E. coli (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and purified using His-tag affinity chromatography (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The efficiency of protein expression and purification was evaluated by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie blue staining, in conjunction with quantitative analysis using ImageJ (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij) to determine sample purity. Phase separation assays were conducted using glass-bottomed dishes. For droplet formation assays, 40 μM protein solutions in buffer containing 10% glycerol, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), and 1.0 mM dithiothreitol were mixed with 10% polyethylene glycol-8000 and imaged with an oil-immersion Olympus FV3000 confocal system [19].

Phase separation in live cells

Cells expressing mCherry-fused proteins or endogenous targets were cultured on glass-bottom dishes (MatTek, Ashland, MA), with nuclear counterstained by DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 10 min. Confocal microscopy (Olympus FV3000) was performed after PBS washes. Phase separation puncta (> 0.5 μm diameter) were analyzed [19].

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP)

The Olympus FV3000 confocal laser scanning microscope was employed to perform FRAP assays in vitro. Target droplets were photobleached for 10 s using alternating 488 nm and 561 nm laser pulses at 50% maximum power, with simultaneous time-lapse imaging (1 frame/s) to monitor fluorescence recovery. All imaging was conducted under controlled environmental conditions (37 °C, 5% CO₂). FRAP assay was conducted in live cells using a climate-controlled chamber. Target regions were bleached (488/561 nm lasers, 50% power, 5 s) and imaged at 500 ms intervals for 60 s (Olympus FV3000, 60 × oil objective). Following background subtraction, the fluorescence intensities were measured and normalized to the average pre-bleach level. All quantifications were performed with FIJI/ImageJ software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij) [19].

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

TEM was performed on tumor cells cultivated in 10-cm dishes and exposed to 2.5% glutaraldehyde. After fixation with 1% osmic acid for 2-3 h, the cells were dehydrated and paraffin-embedded. Ultrathin sections (70 nm) were then contrasted with uranyl acetate and lead citrate prior to observation under a transmission electron microscope (Delong America Inc., Quebec, CA).

Affinity purification

His-tagged MGL_0381 was provided by ChinaPeptides (Shanghai, China). The NHS magenetic beads (HY-K0227, MedChemExpress, Monmouth Junction, NJ) were incubated with 20 mM TCZ or UU-T02 in N,N-dimethylformamide. Following a 2-h incubation at 4 °C with recombinant proteins or nuclear extracts, beads pre-loaded with TCZ or UU-T02 (0.5 mg) were collected. Subsequently, bound proteins were eluted using a lysis buffer containing 0.5% NP-40. Finally, the eluates were analyzed by either immunoblotting or mass spectrometry [26].

Differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF)

Recombinant MYC (GST-tagged) or ARMC12 (His-tagged) proteins were combined with SYPRO Orange dye (Invitrogen) in PBS buffer. The mixture was subjected to a thermal ramp from 40 °C to 90 °C at a rate of 1 °C per minute, with fluorescence intensity monitored at each degree. The resulting data (fluorescence vs. temperature) were fitted to a Boltzmann model for determining the protein melting temperature (Tm) [27].

Cellular viability assay

Viability of cells was determined by the MTT assay (Sigma, a colorimetric method) with absorbance readings taken at 570 nm (reference wavelength 630 nm) [28].

Soft agar assay

Soft agar colony formation assay was performed by suspending 5 × 10³ tumor cells in a mixture of complete medium and 0.05% Noble agar (Thermo Fisher Scientific). This cell suspension was then plated on top of a solidified 0.1% agar base layer in 6-well plates. After incubation for 21 days, colonies were stained with 0.5 mg/mL MTT (Sigma) at 37 °C for 4 h. Viable colonies (> 50 μm diameter) were quantified under a microscope [16, 18-21].

Cellular invasion assay

For the invasion assay, tumor cells (1 × 10⁵) in 200 μL serum-free medium were plated in the upper chamber of Matrigel-coated (1 : 8 dilution) Transwell inserts. The lower chamber was filled with 600 μL of medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Following a 24-h incubation at 37 °C with 5% CO₂, non-invading cells were removed from the upper surface. Cells on the lower membrane surface were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 20 min. After excision, the membranes were mounted on microscope slides for brightfield imaging, and invaded cells were quantified using established criteria [16, 18-21].

Animal model studies

All animal procedures were approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Approval No. 2019-3184) and conducted in compliance with its guidelines. For tumorigenesis and experimental metastasis assays, BALB/c nude mice (n = 5 per group) were randomly allocated and subjective to subcutaneous inoculation of tumor cells (1 × 10⁶) into dorsal flank or intravenous injection of tumor cells (1 × 10⁶) via the tail vein [16, 18-21]. To deplete gastrointestinal fungi, NSG mice (n = 5 per group) received oral gavage of 200 μg amphotericin B daily for five consecutive days, followed by continuous exposure to 0.5 μg/mL amphotericin B in drinking water for 20 days. After completion of anti-fungal therapy, M. globosa (1 × 108 CFU/mL) was administered to repopulate specie-specific fungi by oral gavage, while control group was given PBS by gavage. After 7 days of fungal administration, NSG mice (n = 5 per group) were randomly allocated to receive tumor cell injection (1 × 10⁶ cells in 100 μL PBS) into renal capsule [29]. One week later, 60 mg/kg TCZ or PBS were injected intraperitoneally every other day. After a period of one month, mice were euthanized to assess tumor mass. For in vivo evaluation, tumor cells (1 × 10⁶) were injected either subcutaneously into the dorsal flank or intravenously via the tail vein into BALB/c nude mice; each experimental group consisted of five animals. One week post-inoculation, mice were randomly allocated to receive intravenous administration of MalaEx and intraperitoneal injection of TCZ or UU-T02 (60 mg/kg/day) [16, 18-21]. Tumor volumes and survival of mice were recorded. In vivo imaging was conducted weekly with VIS® Lumina III (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA).

Patient specimens

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College (Approval No. 2023-0519), and was conducted in compliance with both committee's ethical guidelines and principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed written consent was secured from the legal guardians of all participating children. NB tissues were obtained from surgical procedures at Union Hospital, excluding patients with prior chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Tissue samples were immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Following this, their histological identity was verified by a board-certified pathologist. The confirmed specimens were then transferred to a -80 °C freezer for long-term storage until subsequent analysis.

Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemistry, standard protocols [16, 18-21] were employed. Primary antibodies included anti-Ki-67 (1:100; ab92742), anti-CD31 (1:200; ab28364, Abcam), and mAb414 (1:200; ab24609, Abcam). Specificity controls comprised antigen-blocking peptides and isotype-matched IgG. Two blinded pathologists independently scored the immunoreactivity intensity.

Statistical analysis

All quantitative data are summarized as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). For gene expression, thresholds were set based on average values; association between gene sets was tested with Fisher's exact test, and correlation was quantified using Pearson's coefficient. Differences between groups were analyzed with the Mann-Whitney U test (non-parametric data), one-way ANOVA (multiple groups), or Student's t-test (parametric data). Patient survival was plotted via Kaplan-Meier curves, and differences were assessed with the log-rank test. Statistical significance was determined based on two-tailed P values, with a threshold of FDR-adjusted P < 0.05.

Results

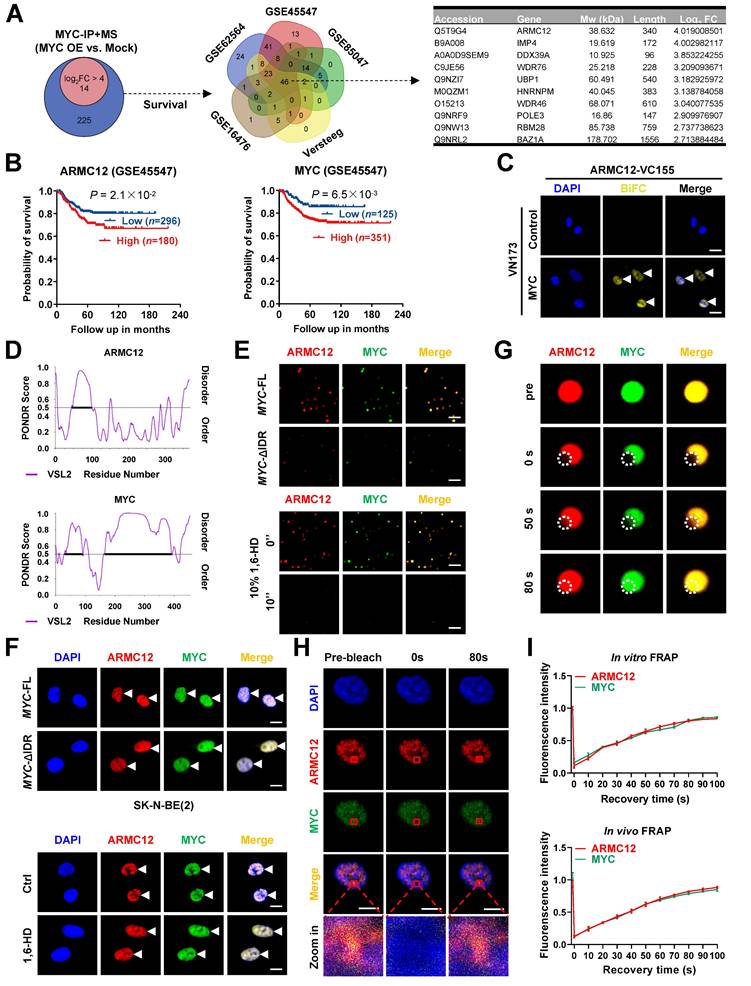

ARMC12 interacts with transcription factor MYC in liquid condensates

Our previous studies have indicated the various MYC expression in cultured NB cell models [16]. For comprehensively profiling the MYC interactome, co-IP coupled with mass spectrometry was performed in SK-N-BE(2) cells (representing relatively low MYC levels) receiving transfection of empty vector or MYC construct. The results revealed 239 candidate proteins enriched in MYC over-expression group (fold changer > 2, P < 0.01, Figure 1A, Figure S1A and Table S4). Comprehensive analysis indicated that 46 proteins were consistently correlated with patients' survival across five independent NB cohorts (n = 498, 649, 283, 122, and 88 from datasets GSE62564, GSE45547, GSE85047, Versteeg, and GSE16476, respectively; Figure 1A). Among them, ARMC12 was top candidate ranking by enrichment fold (Figure 1A and Figure S1B). Elevated ARMC12 or MYC expression was linked to an adverse prognosis in NB cohorts (Figure 1B). Endogenous co-localization of ARMC12 and MYC protein was observed in ganglioneuroblastoma (GNB) or NB specimens, while their Pearson's coefficient was higher in NB tissues (Figure S1C). In addition, ARMC12 was co-localized with MYC in the cellular context of SH-SY5Y and SK-N-AS (Figure S1D). Endogenous ARMC12-MYC complex formation was further confirmed in these NB cells exhibiting intermediate MYC expression (Figure S1E). BiFC assay indicated the complementary fluorescence in SK-N-BE(2) cells co-transfected by ARMC12-VC155 and MYC-NV173 constructs (Figure 1C). Domain mapping experiments indicated that 1-150 amino acids (aa) of MYC was necessary for ARMC12 binding (Figure S1F). Meanwhile, armadillo 2 (ARM2, 206-245 aa) domain, but not armadillo 1 (ARM1, 127-205 aa) or armadillo 3 (ARM3, 246-345 aa) domain, of ARMC12 protein mediated its binding to MYC in SK-N-BE(2) cells harboring FLAG-tagged ARMC12 and HA-tagged MYC constructs (Figure S1F). Given the presence of substantial intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) in both ARMC12 and MYC, as predicted by the PONDR program [30] (Figure 1D), we next sought to investigate their potential to undergo liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS). Imaging with high-resolution fluorescence microscopy revealed that purified recombinant ARMC12-mCherry and MYC-EGFP proteins (purity > 90%; Figure S2A) underwent spontaneous condensation to form biomolecular condensates in vitro (Figure 1E). Meanwhile, deletion of the IDR in MYC abolished the ability of recombinant MYC-EGFP and ARMC12-mCherry proteins to undergo phase separation in vitro (Figure 1E). Consistent with this, pharmacological disruption of LLPS using 1,6-hexanediol (1,6-HD) [31] caused the dissociation of ARMC12-mCherry and MYC-EGFP condensates in vitro (Figure 1E). To examine the physiological relevance, we performed fluorescence imaging in SK-N-BE(2) cells, which revealed analogous compartmentalization of ARMC12 and MYC-EGFP in vivo (Figure 1F). Transfection of MYC-EGFP construct with IDR deletion or treatment with 1,6-HD reduced the LLPS of ARMC12 and MYC-EGFP proteins in NB cells (Figure 1F). To assess the dynamic mobility of these condensates, FRAP assays were performed. Both in vitro and in vivo, ARMC12 and MYC within the droplets exhibited rapid fluorescence recovery (Figure 1G-I), indicating their liquid-like molecular mobility. These findings demonstrated that ARMC12 physically interacted with MYC within liquid biomolecular condensates.

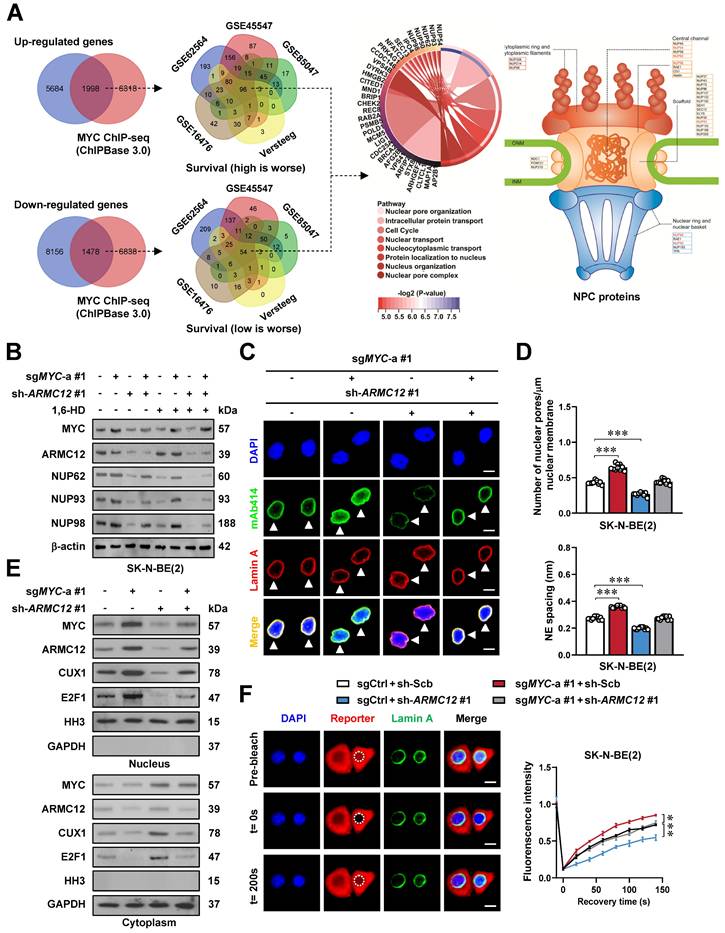

ARMC12/MYC interplay in liquid condensates to drive NPC biogenesis

To further identify downstream targets regulated by ARMC12/MYC in SH-SY5Y cells, RNA-seq transcriptomic analysis was performed following ARMC12 over-expression. This approach revealed 7682 up-regulated and 9634 down-regulated transcripts [fold change (FC) > 1.5, false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted P < 0.05] (Figure 2A). Over-lapping analysis with ChIP-seq datasets in ChIPBase 3.0 [32] revealed that 1998 up-regulated and 1478 down-regulated genes were MYC downstream targets, while 96 and 54 of them were consistently associated with unfavorable or favorable outcome of 498 (GSE62564), 649 (GSE45547), 283(GSE85047), 122 (Versteeg), and 88 (GSE16476) NB patients, respectively (Figure 2A and Table S5). These genes were mainly involved in nuclear pore organization or nuclear transport, including essential NPC components NUP50, NUP54, NUP62, NUP93, and NUP98 (Figure 2A). Mining of a public ChIP-seq dataset (GSE138295) confirmed the enrichment of MYC on promoter regions of NUP50, NUP54, NUP62, NUP93, and NUP98 in NB cells (Figure S2B). Meanwhile, knockdown of MYC in SH-SY5Y cells reduced its binding and transcript levels of NUP62, NUP93, and NUP98, but not of NUP50 or NUP54 (Figure S2C). Following MYC silencing, the promoter activity of NUP62, NUP93, and NUP98 was decreased in a MYC binding site-dependent manner (Figure S2C). Genomic analysis of 2001 NB cases from cBioportal database (https://www.cbioportal.org/) revealed no detectable mutations (missense/nonsense, insertions, or deletions) in NUP62, NUP93, or NUP98 (Figure S2D). Instead, higher levels of NUP62, NUP93, and NUP98 were correlated with mortality, high-risk, advanced stages of International Neuroblastoma Staging System (INSS), or disease progression in 498 NB patients (GSE62564, Figure S2E and Figure S3), and associated with worse survival outcome (Figure S4A-C). In SK-N-BE(2) and SH-SY5Y cells with MYC activation or suppression by clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISP)-deactivated Cas9 (dCas9) [33], dual-luciferase reporter, ChIP-qPCR, real-time qRT-CPR, and immunoblotting analyses indicated the increase or decrease of MYC activity, along with elevation or reduction in MYC enrichment, promoter activity, and expression of target genes (NUP62, NUP93, and NUP98), which was abolished by ARMC12 knockdown or over-expression, respectively (Figure 2B and Figure S5A-F). The interplay of ARMC12 and MYC in regulating expression of these genes was attenuated by 1,6-HD treatment (Figure 2B and Figure S5A-F). Importantly, following induced over-expression of MYC in SK-N-BE(2) cells, there was a significant increase in the NPC number and nuclear envelope (NE) spacing, which was attenuated by ARMC12 silencing (Figure 2C, D and Figure S6A). Additionally, the number of NPC was increased in NB tissues, when compared to that of GNB specimens (Figure S6B).

ARMC12 interacts with transcription factor MYC within liquid condensates in NB cells. (A) Venn diagrams (left and middle panels) showing the identification of differential protein partners [fold change (FC) > 2] of MYC by co-IP coupled with mass spectrometry in SK-N-BE(2) cells stably transfected with empty vector (mock) or MYC, and those consistently associated with survival of 498 (GSE62564), 649 (GSE45547), 283 (GSE85047), 122 (Versteeg), and 88 (GSE16476) NB patients. Table (right panel) revealing top 10 protein partners ranking by FC. (B) Kaplan-Meier curve showing overall survival of 649 NB patients (GSE45547) with high or low expression of ARMC12 or MYC (cutoff values = 7.63 and 12.00). (C) Confocal images of BiFC assay indicating direct interaction between ARMC12 and MYC (arrowheads) in SK-N-BE(2) cells co-transfected with ARMC12-VC155 and MYC-VN173 constructs. Scale bars: 10 μm. (D) IDR within ARMC12 and MYC proteins analyzed by PONDR (http://www.pondr.com/) program. (E) Representative images indicating the liquid droplet formation of ARMC12-mCherry and wild-type or IDR-deficient MYC-EGFP in vitro, and those incubated with vehicle or 10% 1,6-HD. Scale bars: 10 um. (F) Fluorescence imaging assay indicating the condensate formation (arrowheads) of ARMC12 and MYC-EGFP in SK-N-BE(2) cells stably transfected with full-length or IDR-deficient MYC construct, and those incubated with vehicle or 10% 1,6-HD. Scale bars: 10 μm. (G) Representative images of FRAP assay showing the exchange kinetics (circles) of ARMC12-mCherry and MYC-EGFP within condensates. Scale bars: 10 μm. (H) Representative images of FRAP assay showing the exchange kinetics (boxes) of ARMC12 and MYC-EGFP in SK-N-BE(2) cells stably transfected with MYC construct. Scale bars: 10 μm. (I) Quantification of FRAP assay indicating the exchange kinetics of ARMC12-mCherry and MYC-EGFP within condensates in vitro, and that of ARMC12 and MYC-EGFP in vivo. Fisher's exact test for over-lapping analysis in A. Log-rank test for survival comparison in B. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. (error bars) or representative of three independent experiments in C and E-I.

ARMC12/MYC interplay in liquid condensates to drive NPC biogenesis. (A) Venn diagrams of RNA-seq assay (left and middle panels) indicating the alteration of gene expression (fold change > 1.5, P < 0.05) in SH-SY5Y cells stably transfected with empty vector (mock) or ARMC12, and those consistently associated with survival of 498 (GSE62564), 649 (GSE45547), 283 (GSE85047), 122 (Versteeg), and 88 (GSE16476) NB patients. The chord and illustration diagrams (middle and right panels) displaying the involvement of identified 150 genes in GO pathways and NPC formation. (B) Western blot assay showing the expression of MYC, ARMC12, NUP62, NUP93, and NUP98 in SK-N-BE(2) cells stably transfected with control sgRNA (sgCtrl), sgMYC-a #1, scramble shRNA (sh-Scb), or sh-ARMC12 #1, and those treated with vehicle or 10% 1,6-HD. (C) Representative images of immunofluorescence assay indicating the localization and number of NPC (arrowheads) in SK-N-BE(2) cells stably transfected with sgCtrl, sgMYC-a #1, sh-Scb, or sh-ARMC12 #1. (D) Quantification of transmission electron microscopy indicating the NPC numbers and nuclear envelope (NE) spacing in SK-N-BE(2) cells stably transfected with sgCtrl, sgMYC-a #1, sh-Scb, or sh-ARMC12 #1. (E) Western blot assay showing the nuclear or cytoplasmic distribution of MYC, ARMC12, CUX1, or E2F1 in SK-N-BE(2) cells stably transfected with sgCtrl, sgMYC-a #1, sh-Scb, or sh-ARMC12 #1. (F) Representative images (left panel) and quantification (right panel) of FRAP assay indicating the exchange kinetics (circles) of NLS-mCherry-NES reporter within SK-N-BE(2) cells stably transfected with sgCtrl, sgMYC-a #1, sh-Scb, or sh-ARMC12 #1. One-way ANOVA compared the difference in D and F. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. (error bars) or representative of three independent experiments in B-F.

Since gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) indicated the target genes of transcriptional regulators, such as MYC, CUX1, and E2F1, in AMRC12 over-expressing NB cells (Figure S6C), we further observed the potential impact of ARMC12 and MYC on their nuclear translocation. Subcellular fraction and immunoblotting analyses revealed the elevation or reduction in the nuclear abundance of transcriptional regulators MYC, ARMC12, CUX1, and E2F1 upon MYC activation or suppression (Figure 2E and Figure S6D). In FRAP assay using an NLS-mCherry-NES reporter, confocal observation also demonstrated the increase of nuclear transport in SK-N-BE(2) cells with constitutive MYC over-expression (Figure 2F). Meanwhile, ARMC12 depletion or over-expression reversed the alteration of nuclear transport induced by MYC modulation (Figure 2E, F and Figure S6D). Notably, elevated ARMC12 and MYC levels were also linked to poor outcome of adrenocortical sarcinoma, B-cell lymphoma, renal clear cell carcinoma, or breast tumor (Figure S7A-D). These results indicated that ARMC12/MYC interplay in liquid condensates drove NPC biogenesis.

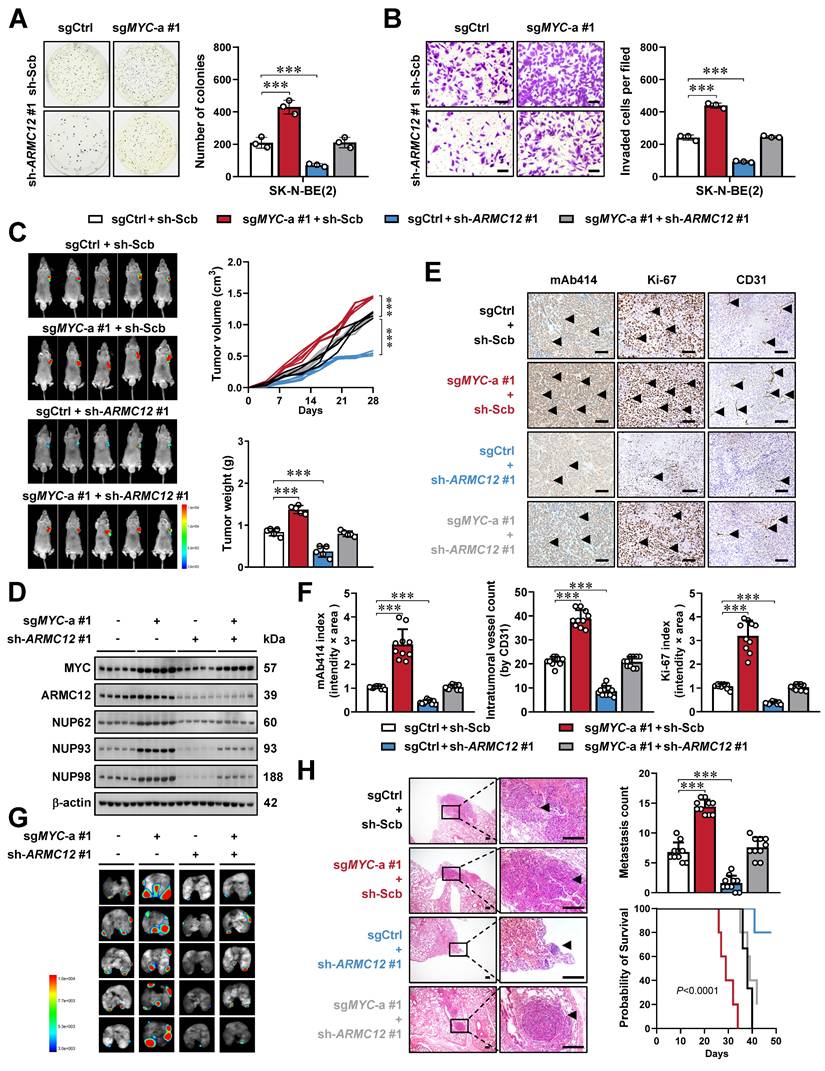

ARMC12/MYC interplay promotes tumorigenesis and aggressiveness of NB

To determine whether ARMC12 functionally intersects with MYC to drive NB aggressiveness, a genetic rescue strategy was employed. Compensatory modulation of ARMC12 expression rescued the oncogenic phenotypes resulting from stable MYC activation or suppression in SK-N-BE(2) and SH-SY5Y cell lines, normalizing their growth and invasive properties (Figure 3A, B and Figure S7E, F). Stable ARMC12 depletion rescued the MYC-driven tumor-promoting phenotype in SK-N-BE(2) xenografts in nude mice. Specifically, it reversed enhancement in tumor growth, mass, and expression of downstream genes (NUP62, NUP93, and NUP98) (Figure 3C, D), accompanied by modulation of NPC numbers and Ki-67 or CD31 labeling index (Figure 3E, F). In addition, tail vein injection of MYC over-expressing SK-N-BE(2) cells into nude mice led to a marked increase in lung metastasis and a concomitant decline in overall condition, as evidenced by shortened survival and decreased body weight, and these alterations were reversed by ARMC12 knockdown (Figure 3G, H and Figure S7G). Above findings indicated that ARMC12/MYC interplay promoted tumorigenesis and aggressiveness of NB.

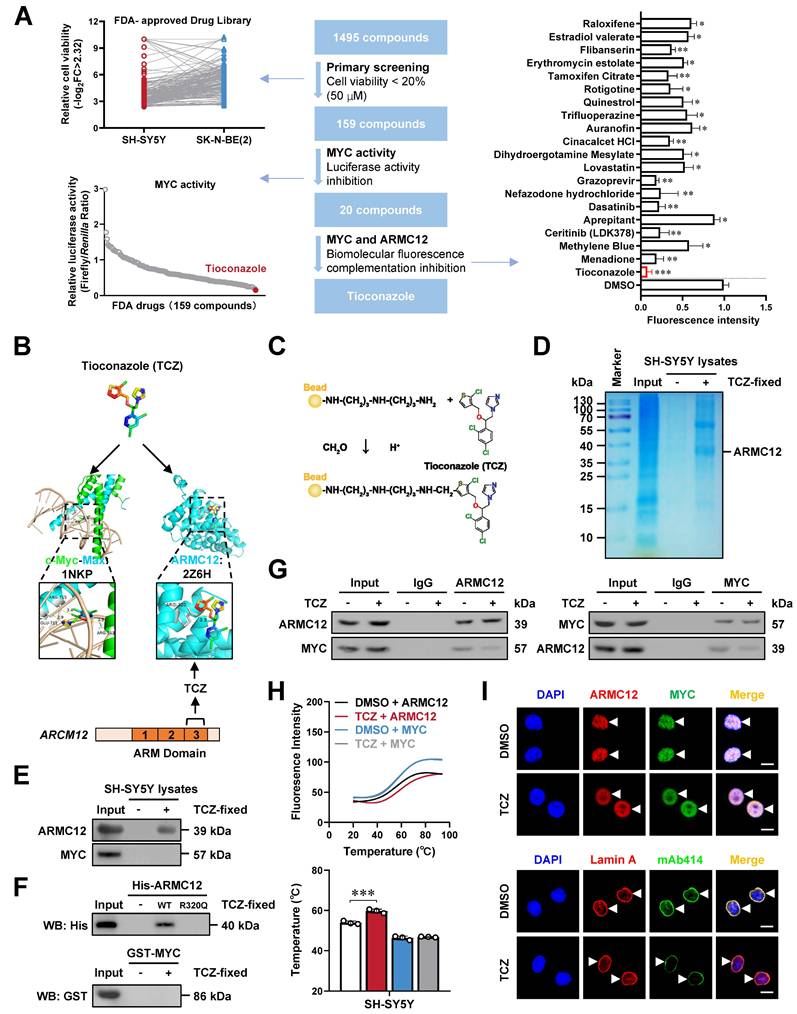

Tioconazole inhibits the ARMC12-MYC interaction in NB cells

To identify inhibitors of AMRC12-MYC interaction, NB cells were exposed to 1495 Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs (Figure 4A). Among them, 159 compounds reduced cell viability by over 80% (Figure 4A, Table S6). Subsequent dual-luciferase assay revealed that 20 of these compounds suppressed MYC activity by more than 80% (Figure 4A, Table S6). BiFC screening identified tioconazole (TCZ), menadione, and ceritinib as inhibitors of ARMC12-MYC interaction, with TCZ showing the strongest suppression (Figure S8A). In cultured NB cells, TCZ inhibited the viability in a dose-dependent manner (Figure S8B). The HDOCK molecular docking program (http:// hdock.phys.hust.edu.cn/) predicted the binding of TCZ to ARM3 domain, especially amino acid residue 320 (3.5 Å distance), of ARMC12 protein (Figure 4B). Affinity purification [26] and mass spectrometry assays indicated 146 TCZ-enriched proteins from SH-SY5Y cell lystaes (Table S7), while 16 candidates were linked to survival outcomes in five publicly available NB datasets, encompassing 498 (GSE62564), 649 (GSE45547), 283 (GSE85047), 122 (Versteeg), and 88 (GSE16476) patients (Figure S9A). Among them, ARMC12 was top candidate ranking by enrichment fold (Figure S9A). Validating affinity purification and western blot assays indicated the TCZ-enriched ARMC12, but not MYC protein, from SH-SY5Y cell lystaes (Figure 4C-E). Moreover, TCZ directly interacted with recombinant wild-type ARMC12 protein rather than its mutant in amino acid residue 320 or recombinant MYC protein (Figure 4F). Importantly, following TCZ treatment, the interaction between ARMC12 and MYC was markedly weakened in SH-SY5Y and SK-N-AS cells, as evidenced by co-IP coupled with western blot analyses (Figure 4G and Figure S9B), and this inhibitory effect was biochemically confirmed through DSF measurements [27] (Figure 4H). Meanwhile, mutation of 320th amino acid reversed the repressive effects of TCZ on ARMC12-MYC interaction (Figure S9C), and prevented the decrease in MYC activity, MYC enrichment, promoter activity, and expression of target genes (NUP62, NUP93, NUP98) induced by TCZ treatment in SH-SY5Y cells (Figure S9D-F). Of note, TCZ treatment reduced the LLPS of ARMC12 and MYC (Figure 4I), and decreased the NPC number in SH-SY5Y cells (Figure 4I). These results suggested that TCZ inhibited the ARMC12-MYC interaction in NB cells.

ARMC12/MYC interplay promotes tumorigenesis and aggressiveness of NB in vitro and in vivo. (A and B) Representative images (left panel) and quantification (right panel) of soft agar (A) and Matrigel invasion (B) assays showing the growth and invasion of SK-N-BE(2) cells stably transfected with control sgRNA (sgCtrl), sgMYC-a #1, scramble shRNA (sh-Scb), or sh-ARMC12 #1 (n = 3). Scale bars: 50 μm. (C) Representative images (left panel), growth curve (right upper panel), and weight (right lower panel) of subcutaneous xenograft tumors formed by SK-N-BE(2) cells stably transfected with sgCtrl, sgMYC-a #1, sh-Scb, or sh-ARMC12 #1 in nude mice (n = 5 per group). (D) Western blot assay showing the expression of MYC, ARMC12, NUP62, NUP93, and NUP98 in xenograft tumors formed by SK-N-BE(2) cells stably transfected with sgCtrl, sgMYC-a #1, sh-Scb, or sh-ARMC12 #1 in nude mice. (E and F) Representative images (E) and quantification (F) of immunohistochemistry indicating the expression of NPC, Ki-67, and CD31 (arrowheads) in xenograft tumors formed by SK-N-BE(2) cells stably transfected with sgCtrl, sgMYC-a #1, sh-Scb, or sh-ARMC12 #1 in nude mice (n = 5 per group). Scale bars: 100 μm. (G and H) Representative images (G), H&E staining (H, arrowheads) or quantification (H) of lung metastasis, and Kaplan-Meier curves (H) of nude mice treated with tail vein injection of SK-N-BE(2) cells stably transfected with sgCtrl, sgMYC-a #1, sh-Scb, or sh-ARMC12 #1 in nude mice (n = 5 per group). Scale bars: 150 μm. One-way ANOVA compared the difference in A-C, F and H. Log-rank test for survival comparison in H. *** P < 0.001. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. (error bars) or representative of three independent experiments in A-H.

Tioconazole inhibits the interaction between ARMC12 and MYC in NB cells. (A) MTT colorimetric, dual-luciferase, and BiFC assays revealing the screening of ARMC12-MYC interaction inhibitor from 1495 FDA-approved drugs in NB cells. (B) Molecular docking analysis of TCZ with MYC or ARMC12 protein via HDOCK program (http://hdock.phys.hust.edu.cn/). (C-E) Chemical structure (C), Coomassie blue staining (D), and western blot (E) assays showing the binding of ARMC12 or MYC within SH-SY5Y cell lystaes to NHS beads covalently conjugated with TCZ (20 μM). (F) Western blot assay indicating the affinity of recombinant wild-type or R320Q mutant ARMC12 or MYC protein to NHS beads covalently conjugated with TCZ (20 μM). (G) Co-IP and western blot assays showing the interaction between ARMC12 and MYC in SH-SY5Y cells treated with solvent or TCZ (20 μM). (H) DSF assay (upper panel) and temperature (lower panel) showing the fluroresence intensity of His-tagged ARMC12 or GST-tagged MYC protein incubated with DMSO or TCZ (20 μM). (I) Fluorescence imaging assay (upper panel) indicating the condensate formation (arrowheads) of ARMC12 and MYC-EGFP in SK-N-BE(2) cells stably transfected with MYC construct, and those incubated with DMSO or TCZ (20 μM). Representative images (lower panel) of immunofluorescence assay indicating the localization and number of NPC (arrowheads) in SK-N-BE(2) cells incubated with DMSO or TCZ (20 μM). Scale bars: 10 μm. One-way ANOVA compared the difference in A and H. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. (error bars) or representative of three independent experiments in A and D-I.

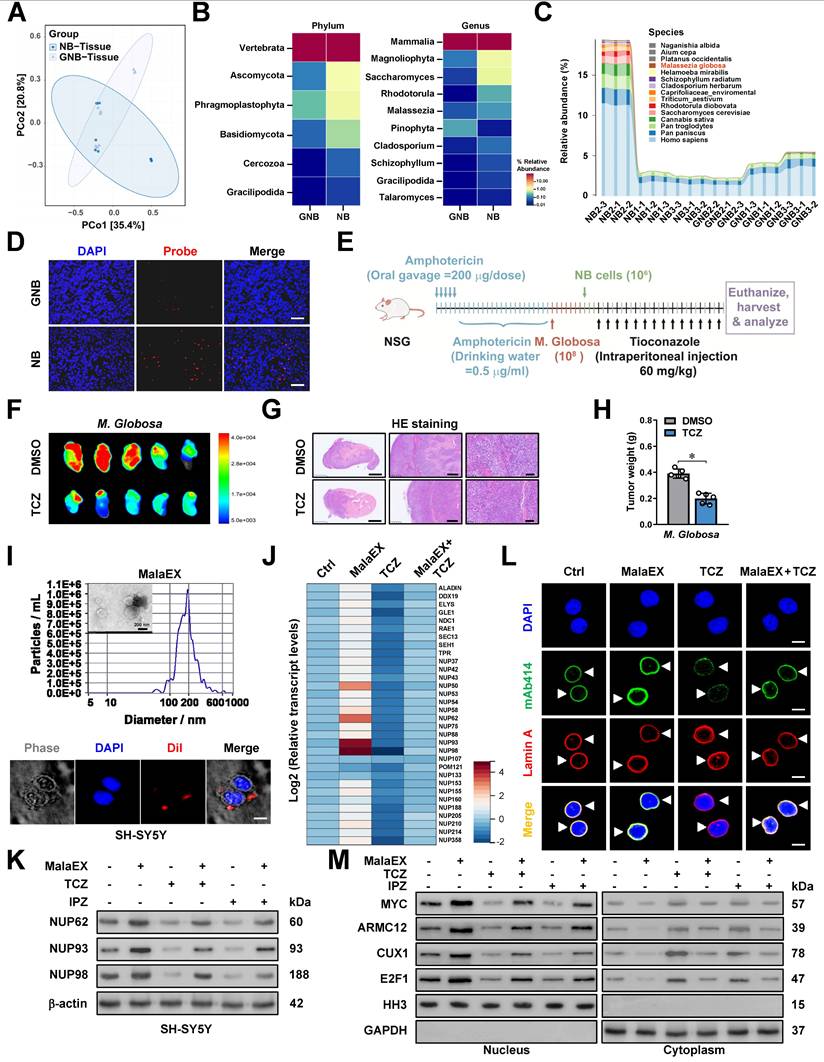

M. globosa extracellular vesicles facilitate NPC biogenesis and tumorigenesis

Since TCZ is an established anti-fungal drug, we hypothesized that it might also affect the intratumoral fungi driving tumorigenesis. The mycobiome analysis using 18S rRNA sequencing indicated the consistent existence of fungi within NB and GNB tissues (Figure 5A). Of note, fungi of various phylum, class, order, family, or genus were differentially detected between NB and GNB specimens (Figure 5B, Figure S10A-C and Table S8). Among them, M. globosa, an oncogenic fungi driving PDAC progression [24], was obviously enriched in NB tissues (Figure 5C) and chosen for further studies. Fungal FISH validated the elevated abundance of M. globosa in NB tissues (Figure 5D). To evaluate the effects of M. globosa on NB progression, amphotericin B pretreatment was performed in NSG mice prior to oral gavage administration of fungal strain (Figure 5E). There was significant M. globosa colonization, growth, and renal invasion of SH-SY5Y-derived xenograft tumors under renal capsule of these NSG mice, which was attenuated by intraperitoneal injection of TCZ (Figure 5E-G and Figure S10D, E), accompanying by decrease in tumor weight (Figure 5H). Since previous studies revealing the oncogenic roles of fungi EVs [34], we isolated EVs from M. globosa culture medium (designated MalaEX) and confirmed their structural integrity through electron microscopy and particle size analysis (Figure 5I). The internalization efficiency of Dil-labeled EVs by NB cells was subsequently quantified via immunofluorescence assay (Figure 5I). MalaEX incubation up-regulated the mRNA expression of NUP62, NUP93, and NUP98 in SH-SY5Y cells, whereas TCZ treatment reversed this effect (Figure 5J). Western blot assay revealed that MalaEX treatment up-regulated NUP62, NUP93, and NUP98 protein levels of NB cells (Figure 5K and Figure S10F). However, this upregulation was abolished upon administration of TCZ or importazole (IPZ), a validated inhibitor targeting importin-β-dependent nuclear transport pathway (Figure 5K and Figure S10F). Consistently, NPC biogenesis of SH-SY5Y cells was facilitated by MalaEX incubation, while TCZ treatment attenuated these effects (Figure 5L). The nuclear translocation of MYC, ARMC12, and other transcriptional regulators (CUX1 or E2F1) was enhanced in NB cells incubated with MalaEX, which was reversed by TCZ or IPZ treatment (Figure 5M and Figure S10G). These results suggested that M. globosa extracellular vesicles facilitated NPC biogenesis and tumorigenesis.

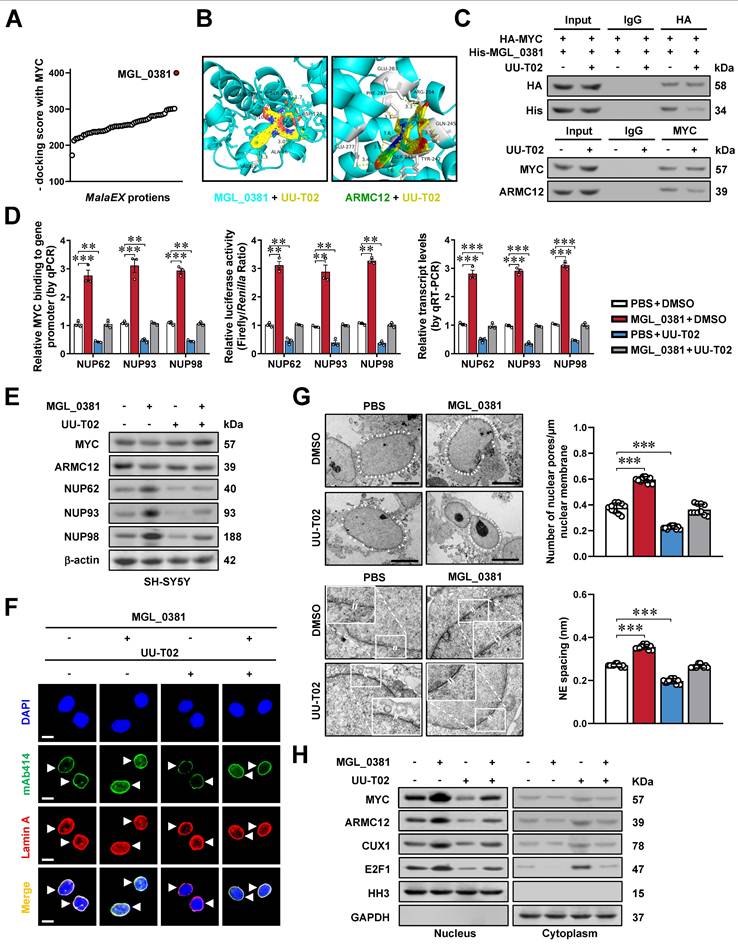

MGL_0381 facilitates MYC transactivation and NPC biogenesis

To further investigate the roles of MalaEX in NPC biogenesis, we performed proteomic profiling to detect diverse protein contents (Figure S10H), followed by molecular docking analysis with MYC protein via HDOCK server (http://hdock.phys.hust.edu.cn/). Among them, MGL_0381 was found to achieve highest docking score (Figure 6A). Of note, both MGL_0381 and AMRC12 contained Armadillo-like helical or fold similar to that of β-catenin (Figure S11A), while their potential binding with UU-T02, an established β-catenin inhibitor [35], was evaulated by molecular docking via HDOCK program (Figure 6B). The NHS beads-mediated affinity purification assay indicated direct interaction of UU-T02 with recombinant MGL_0381 or ARMC12, but not with MYC protein (Figure S11B, C and Table S9). Meanwhile, mutation of amino acid residue 242, but not of amino acid residue 241 or 245, within ARM2 domain, abolished the interaction of ARMC12 with UU-T02 (Figure S11D). In addition, UU-T02 treatment reduced the binding of MGL_0381 or ARMC12 to MYC protein in NB cells (Figure 6C). In SH-SY5Y cells, administration of recombinant MGL_0381 protein led to a significant elevation in MYC enrichment, concomitant with an augmentation in promoter activity, transcript levels, and protein expression of NUP62, NUP93, and NUP98 (Figure 6D, E), resulting in enhanced NPC biogenesis (Figure 6F, G) and nuclear transport of transcriptional regulators (Figure 6H). Meanwhile, UU-T02 treatment reversed these alterations induced by MGL_0381 protein (Figure 6D-H). These findings suggested that as a protein content of MalaEX, MGL_0381 facilitated MYC transactivation and NPC biogenesis.

M. globosa extracellular vesicles facilitate NPC biogenesis and tumorigenesis. (A-C) Mycobiome analysis using 18S rRNA sequencing indicating the principal components (PC, A), phylum (B), genus (B), and species (C) of fungi within NB and GNB tissues. (D) Fungal FISH assay validating the elevated abundance of M. globosa in NB tissues, than that of GNB specimens. (E-G) Representative images (F) and H&E staining (G) showing the growth and renal invasion of SH-SY5Y-formed xenograft tumors under renal capsule of NSG mice receiving oral gavage of amphotericin B, M. globosa, and intraperitoneal injection of TCZ as indicated (E). (H) Tumor weight of NSG mice receiving oral gavage of amphotericin B, M. globosa, and intraperitoneal injection of TCZ. (I) Electron microscopic analysis and particle size assay (upper panel) validating the EVs extracted from culture medium of M. globosa (MalaEX), with the uptake of Dil-labeled EVs by NB cells observed under a confocal microscope. (J) Real-time qRT-PCR assay revealing the transcript levels (normalized to β-actin, n = 5) of NPC biogenesis genes in SH-SY5Y cells treated with MalaEx or TCZ (20 μM). (K) Western blot assay showing the expression of NUP62, NUP93, and NUP98 in SH-SY5Y cells treated with MalaEx, TCZ (20 μM), or IPZ (20 μM). (L) Representative images of immunofluorescence assay indicating the localization and number of NPC (arrowheads) in SH-SY5Y cells treated with MalaEx or TCZ (20 μM). (M) Western blot assay showing the nuclear or cytoplasmic distribution of MYC, ARMC12, CUX1, or E2F1 in SH-SY5Y cells treated with MalaEx, TCZ (20 μM), or IPZ (20 μM). Student's t test compared the difference in H. * P < 0.05. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. (error bars) or representative of three independent experiments in C, D and F-M.

MGL_0381 facilitates MYC transactivation and NPC biogenesis. (A) Molecular docking of MalaEX content proteins with MYC via HDOCK program (http://hdock.phys.hust.edu.cn/). (B) Molecular docking of MGL_0381 or ARMC12 protein with UU-T02 via HDOCK program. (C) Co-IP and western blot assays showing the interaction between HA-tagged MYC and His-tagged MGL_0381 protein in SK-N-BE(2) cells transfected with MYC construct, endogenous interaction of MYC with ARMC12 in SH-SY5Y cells, and those incubated with DMSO or UU-T02 (1.0 μM). (D) ChIP-qPCR (normalized to input, n = 3), dual-luciferase (n = 3), and real-time qRT-PCR (normalized to β-actin, n = 3) assays indicating the MYC enrichment, promoter activity, and transcript levels of NUP62, NUP93, or NUP98 in SH-SY5Y cells treated with PBS or recombinant MGL_0381, and those incubated with DMSO or UU-T02 (1.0 μM). (E) Western blot assay showing the expression of MYC, ARMC12, NUP62, NUP93, and NUP98 in SH-SY5Y cells treated with PBS or recombinant MGL_0381, and those incubated with DMSO or UU-T02 (1.0 μM). (F and G) Representative images and quantification of immunofluorescence assay (F) and transmission electron microscopy (G) indicating the NPC number (arrowheads) and nuclear envelope (NE) spacing in SH-SY5Y cells treated with PBS or recombinant MGL_0381, and those incubated with DMSO or UU-T02 (1.0 μM). (H) Western blot assay showing the nuclear or cytoplasmic distribution of MYC, ARMC12, CUX1, or E2F1 in SH-SY5Y cells treated with PBS or recombinant MGL_0381, and those incubated with DMSO or UU-T02 (1.0 μM). One-way ANOVA compared the difference in D and G. ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. (error bars) or representative of three independent experiments in C-H.

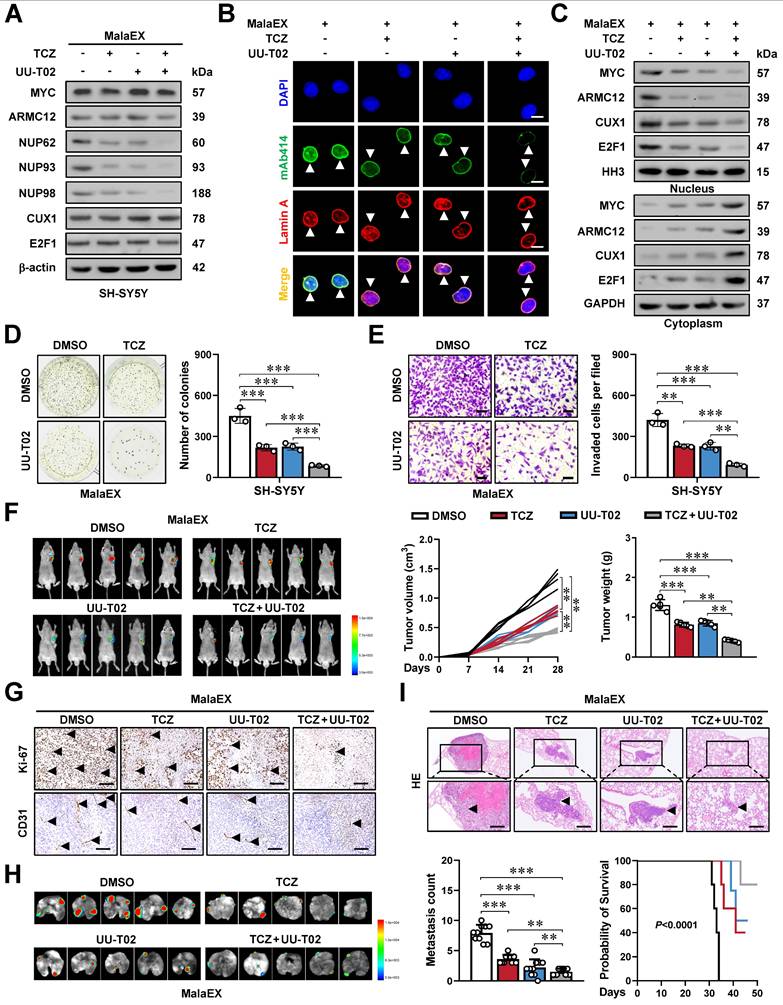

Synergetic targeting AMRC12- and MGL_0381-facilitated MYC transactivation inhibits NPC biogenesis and NB progression

We subsequently assessed the impact of targeting AMRC12- and MGL_0381-facilitated MYC transactivation on tumorigenesis and aggressiveness. Administration of TCZ and UU-T02 directly inhibited the phase-separated biomolecular condensates of ARMC12 and MYC in vitro (Figure S11E), and exerted synergetic effects in reducing the MYC enrichment, promoter activation, and expression of target genes (NUP62, NUP93, NUP98), NPC biogenesis, and nuclear transport of transcriptional regulators in MalaEX-treated SH-SY5Y and SK-N-AS cells (Figure 7A-C, Figure S11F, and Figure S12A, B). Combined treatment with TCZ and UU-T02 synergistically suppressed both colony formation in soft agar and invasive capacity through Matrigel in MalaEX-exposed NB cells (Figure 7D, E and Figure S12C, D). The TCZ/UU-T02 combination showed more tumor suppression efficiency in SH-SY5Y xenografts compared to monotherapies, significantly inhibiting tumor volume, mass, proliferative activity (Ki-67 index), and angiogenesis (CD31+ vessels), with no obvious toxicity in the heart, liver, or kidney of nude mice models (Figure 7F, G and Figure S12E, F). In addition, the TCZ/UU-T02 combination administered via tail vein markedly suppressed SH-SY5Y-derived pulmonary metastasis, extended survival, and improved body weight of nude mice compared to single-agent regimens (Figure 7H, I and Figure S12G). Taken together, these results indicated that synergetic targeting AMRC12- and MGL_0381-facilitated MYC transactivation inhibited NPC biogenesis and NB progression.

Discussion

The MYC family of transcription factors (MYC, MYCN, L-MYC) serves as pivotal oncogenic drivers in neuroendocrine tumors, such as cancers of the lung, pancreas, gastrointestinal tract, prostate, and NB [36]. MYC protein binds E-box sequences (CACGTG) in target gene promoters, priming chromatin for active transcription [37]. The MYC amplifications is noted in 15-20% of individuals diagnosed with small-cell lung cancer, and implicated in chemoresistance, tumor progression, or poor survival [38]. In MYC-hyperactive tumors, MYC cooperates with E2F at promoters to amplify transcriptional output, accelerating cell cycle progression and proliferation [39]. MYC promotes uncontrolled proliferation of tumor cells by activating cyclin-dependent kinase 4 in cell cycle S-phase entry [40] and fuels metabolic reprogramming via aerobic glycolysis or biosynthetic intermediate production [41]. MYC also facilitates ribosomal DNA transcription by enhancing RNA polymerase I preinitiation complex assembly [42, 43]. Proteomic studies reveal 336 high-confidence MYC partners, such as acetyltransferases, RNA processing factors, and ribosome biogenesis machinery, underscoring its multifaceted role in oncogenesis [44]. Actually, the activity of MYC is regulated by binding partners, such as bromodomain containing 4 (BRD4) [45], non-POU domain containing octamer binding [21], or lamin A/C [16]. Meanwhile, targeting MYC expression or activity is a potential therapeutic strategy for tumors. For example, MYCi975 is able to destabilize MYC via Helix-Loop-Helix domain binding and T58 phosphorylation [46], while Omomyc, a dominant-negative mini-protein, displaces MYC from E-boxes to suppress gene transcription [47]. BET inhibitors are able to attenuate MYC activity by blocking BRD4-mediated chromatin remodeling [48]. Herein, we discover that MYC facilitates the expression of NUP62, NUP93, and NUP98, resulting in elevation of NPC biogenesis, growth, and invasion capability of NB cells. In addition, our data demonstrate that ARMC12 engages with MYC within liquid-liquid phase-separated condensates to potentiate its transactivating function. This ARMC12-MYC interplay propels tumor growth and enhances aggressiveness (Figure 8), underscoring the pivotal role of the ARMC12/MYC axis in driving NB progression.

Armadillo repeat-containing proteins (ARMCs), a conserved eukaryotic protein family characterized by tandem repeats of ARM domains, play pivotal roles in cell adhesion, signal transduction, cytoskeletal regulation, mitochondrial dynamics, and tumorigenesis [49]. In current study, a functional relationship between ARMC12 and MYC activities is illuminated in NB. ARMC12 is highly conserved in primates (99% identity in gorillas, 84% in mice), and regulates mitochondrial dynamics during spermiogenesis [50]. Our previous evidences establish ARMC12 as a critical cofactor of RB binding protein 4 in enhancing polycomb repressive complex 2 activity, thus silencing tumor suppressive genes and promoting proliferation of NB cells [15]. Canonical ARMCs such as β-catenin, plakoglobin, and plakophilin utilize their ARM domains for protein-protein interactions [51]. We demonstrated that ARM2 domain of ARMC12 protein mediated its binding to MYC, leading to elevation of MYC transactivation in NB cells. In addition, ARMC12 promoted NPC biogenesis during NB progression, at least in part, through elevation of MYC activation.

Synergetic targeting AMRC12- and MGL_0381-facilitated MYC transactivation inhibits NPC biogenesis and NB progression. (A) Western blot assay showing the expression of MYC, ARMC12, NUP62, NUP93, and NUP98 in SH-SY5Y cells treated with MalaEx, TCZ (20 μM), or UU-T02 (1.0 μM). (B) Representative images of immunofluorescence assay indicating the localization and number of NPC (arrowheads) in SH-SY5Y cells treated with MalaEx, TCZ (20 μM), or UU-T02 (1.0 μM). (C) Western blot assay showing the nuclear or cytoplasmic distribution of MYC, ARMC12, CUX1, or E2F1 in SH-SY5Y cells treated with MalaEx, TCZ (20 μM), or UU-T02 (1.0 μM). (D and E) Representative images (left panel) and quantification (right panel) of soft agar (D) and Matrigel invasion (E) assays showing the growth and invasion of SH-SY5Y cells treated with MalaEx, TCZ (20 μM), or UU-T02 (1.0 μM, n = 3). Scale bars: 50 μm. (F) Representative images (left panel), growth curve (middle panel), and tumor weight (middle panel) of subcutaneous xenograft tumors formed by SH-SY5Y cells in nude mice that received intravenous administration of MalaEx and intraperitoneal injection of TCZ (60 mg/kg/day) or UU-T02 (60 mg/kg/day, n = 5 per group). (G) Representative images of immunohistochemistry indicating the immunostaining of Ki-67 and CD31 (arrowheads) in subcutaneous xenograft tumors formed by SH-SY5Y cells in nude mice that received administration of MalaEx, TCZ (60 mg/kg/day), or UU-T02 (60 mg/kg/day). Scale bars: 100 μm. (H and I) Representative images (H), H&E staining (I, arrowheads) or quantification (I) of lung metastasis, and Kaplan-Meier curves (I) of nude mice treated with tail vein injection of SH-SY5Y cells in nude mice that received administration of MalaEx, TCZ (60 mg/kg/day), or UU-T02 (60 mg/kg/day, n = 5 per group). One-way ANOVA compared the difference in D-F and I. Log-rank test for survival comparison in I. ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. (error bars) or representative of three independent experiments in A-I.

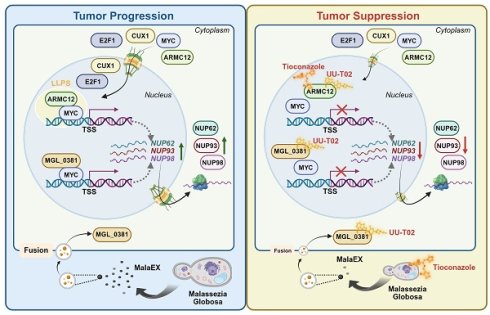

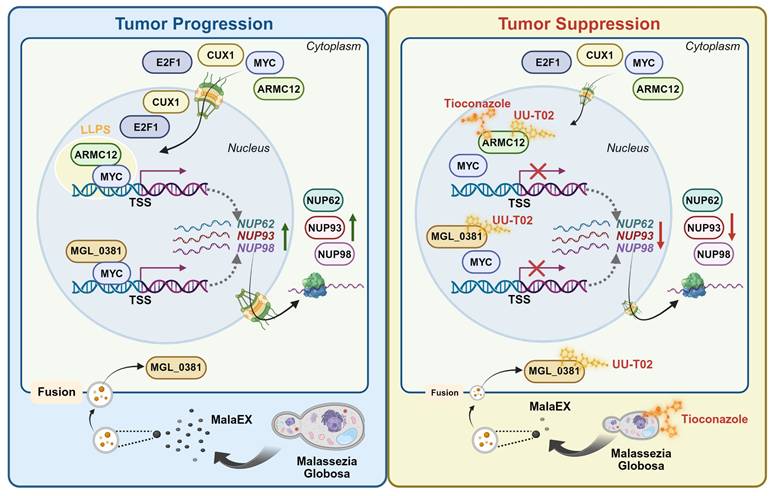

Mechanisms underlying synergetic effects of AMRC12- and MGL_0381 in driving NPC biogenesis and progression of NB. As a co-factor, AMRC12 binds with and activates transcription factor MYC in liquid condensates to facilitate target gene (NUP62, NUP93, and NUP98) expression, resulting in increase of NPC biogenesis and NB progression. In addition, as the protein content of extracellular vesicles (MalaEX) of M. globosa, MGL_0381 also physically interacts with and activates MYC protein to drive these target gene expressions. Meanwhile, anti-fungi tioconazole (TCZ) was able to block the interaction between ARMC12 and MYC, while UU-T02 binds with AMRC12 or MGL_0381 to suppress their interaction with MYC. Administration of both TCZ and UU-T02 exerts synergetic effects in repressing MYC transactivation, resulting in inhibition of NPC biogenesis and progression of NB.

Recent evidences show the colonization of fungi within cancer tissues [52]. For instance, pancreatic neoplasms exhibit the significant elevation in fungal biomass relative to normal counterparts, with mycobiota composition dominated by M. globosa, Aspergillus, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae [24]. Notably, M. globosa, a lipophilic basidiomycetous yeast traditionally linked to dermatological conditions, has emerged as a critical oncogenic commensal in multiple cancers [24, 53, 54]. M. globosa is enriched in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), breast carcinomas, and gastric malignancies, and serves as a predictive biomarker for adverse clinical outcomes [24, 53, 54]. In PDAC, M. globosa accelerates oncogenesis via mannose-binding lectin signaling, and its removal via antifungal therapy (e.g., amphotericin B) reduces tumor burden and improves prognosis of mice [24]. Similarly, M. globosa colonization promotes breast cancer progression by inducing interleukin 17A-driven M2 macrophage polarization [53]. Of note, M. globosa encodes enzymes (esterases, lipases, proteases) that disrupt epithelial barriers, degrade extracellular matrix, or amplify inflammatory cascades, which collectively drive cancer progression [55]. In this study, we found that M. globosa colonized within NB tissues, and served as an oncogenic mediator to drive NB progression. As lipid-bound nanosized particles (10-400 nm) releasing from all domains of life (eukaryotes, bacteria, fungi, archaea), EVs serve as critical mediators of intercellular and cross-kingdom communication by transporting proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, or metabolites [56]. Bacterial EVs deliver immunomodulatory signals to up-regulate programmed death-ligand 1 in pulmonary carcinoma via signaling cascade from Toll-like receptor 4 to nuclear factor kappa B [34]. In fungi, EVs were first identified in Cryptococcus neoformans in 2007, and have since been characterized in 11 additional species, such as Candida albicans, Aspergillus fumigatus, and Paracoccidioides brasiliensis [56]. Fungal EVs facilitate unconventional export of proteins or specie-specific cargo involved in stress response or signaling transduction [56], and regulate intraspecies interactions [56]. Notably, Malassezia species produce EVs that influence microbial community dynamics and host-pathogen crosstalk [57]. In this investigation, we employed mass spectrometry to identify MGL_0381 as a protein content within EVs of M. globosa. Of importance, MGL_0381 promoted NPC biogenesis and NB progression by facilitating MYC transactivation. Disruption of MGL_0381-MYC interaction suppressed the malignant behaviors of NB cells, which underscores the critical role of MGL_0381 in NB pathogenesis.

Tioconazole (TCZ), an antifungal drug, is able to occupy the active sites of autophagy-related proteases autophagy related 4A (ATG4A) or autophagy related 4B (ATG4B), and directly block their enzymatic activity [58], thus diminishing autophagic flux in cancer cells under stress conditions [58]. These findings position TCZ as a promising candidate for tumor treatment. In this study, using a novel drug discovery platform that integrates computational docking, biochemical assays, and cellular reporter systems, we identified that TCZ bound with ARMC12 to disrupt its interaction with MYC in NB cells, while underlying alteration in spatial conformation of ARMC12 protein warrants further investigation. Especially, our evidences demonstrate that administration of TCZ and UU-T02 exerts synergetic effects to inhibit NPC biogenesis and progression of NB. Meanwhile, further studies are needed to explore their effects and alternative acting mechanisms for tumor treatment in immunocompetent mice.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study provides inaugural evidence that ARMC12/MYC-modulated transcriptional targets in NPC correlate with adverse clinical outcomes and function as critical drivers of NB pathogenesis. The mechanistic basis involves ARMC12, which functions within liquid-liquid phase-separated condensates to co-activate MYC, driving the subsequent up-regulation of NUP62, NUP93, and NUP98, elevation of NPC number, and tumor progression. As a protein content within EVs of M. globosa, MGL_0381 also facilitates MYC transactivation via physical interaction to drive NPC biogenesis. Targeting both ARMC12-MYC and MGL_0381-MYC interaction exerts synergetic inhibitory effects on NPC biogenesis and NB progression. Collectively, our study elucidates the transcriptional regulatory networks governing NPC biogenesis and NB progression. Specifically, we uncover the pivotal roles of a fungal-derived protein and ARMC12/MYC axis in these processes, thereby highlighting their potential as novel therapeutic targets in oncology.

Abbreviations

1,6-HD: 1,6-hexanediol; AGC: automatic gain control; ANOVA: analysis of variance; ARMC12: armadillo repeat containing 12; ARMCs: Armadillo repeat-containing proteins; ATCC: American Type Culture Collection; BiFC: bimolecular fluorescence complementation; ChIP: chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing; ChIP-seq: chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing; co-IP: co-immunoprecipitation; CRISP: clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats; CUX1: cut like homeobox 1; DAPI: 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; dCas9: deactivated Cas9; DDA: data-dependent acquisition; DSF: differential scanning fluorimetry; E2F1: E2F transcription factor 1; EVs: extracellular vesicles; FDA: Food and Drug Administration; FISH: fluorescence in situ hybridization; FPKM: fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads; FRAP: fluorescence recovery after photobleaching; GAPDH: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GEO: Gene Expression Omnibus; GNB: ganglioneuroblastoma; GSEA: gene set enrichment analysis; GST: glutathione S-transferase; HA: hemagglutinin; HH3: histone H3; IDR: intrinsically disordered region; INSS: International Neuroblastoma Staging System; IPZ: importazole; ITS: Internal Transcribed Spacer; LC-MS/MS: liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry; LLPS: liquid-liquid phase separation; NB: neuroblastoma; NE: nuclear envelope; NPC: nuclear pore complex; NUP: nucleoporin; PAGE: polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; PBS: phosphate-buffered saline; PDAC: pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; PVDF: polyvinylidene fluoride; qPCR: quantitative PCR; qRT-PCR: quantitative RT-PCR; RNA-seq: RNA sequencing; SDS: sodium dodecyl sulfate; SEM: standard error of the mean; sgRNA: small guide RNA; shRNA: short hairpin RNA; sh-Scb: scramble shRNA; TCZ: tioconazole; TEM: transmission electron microscopy.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures and tables.

Acknowledgements

Figure 8 was created by BioRender program (www.biorender.com).

Funding

This work was granted by the Major Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (82293663, 82293660), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (82072801, 82173316, 82473092).

Ethics approval

The acquisition of tumor tissues has been endorsed by the Institutional Review Board of Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College (Approval No. 2023-0519). All procedures that involved animals were approved by the Experimental Animal Ethics Committee at Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Approval No. 2019-3184).

Data availability statement

The RNA-seq data are accessible in the GEO database under the accession numbers GSE107516 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). Additional datasets were obtained from the GEO database (accessions: GSE62564, GSE45547, GSE85047, GSE16476, GSE138295) or the R2 platform (https://hgserver2.amc.nl/, ps_amc_combatnb122_ u133p2). All remaining datasets are provided in the main manuscript and supplementary materials.

Author contributions

Anpei Hu and Chunhui Yang conceived and performed most of the experiments; Zhijie Wang, Xiaolin Wang, Xinyue Li, Jiaying Qu, Shunchen Zhou, Bosen Zhao, and Xiaojing Wang accomplished some of in vitro experiments; Anpei Hu accomplished in vivo studies; Anpei Hu and Xiaojing Wang undertook the mining of publicly available datasets; Qiangsong Tong and Liduan Zheng wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Qiu B, Matthay KK. Advancing therapy for neuroblastoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19:515-33

2. Sainero-Alcolado L, Sjöberg Bexelius T, Santopolo G, Yuan Y, Liaño-Pons J, Arsenian-Henriksson M. Defining neuroblastoma: From origin to precision medicine. Neuro Oncol. 2024;26:2174-92

3. Zimmerman MW, Liu Y, He S, Durbin AD, Abraham BJ, Easton J. et al. MYC drives a subset of high-risk pediatric neuroblastomas and is activated through mechanisms including enhancer hijacking and focal enhancer amplification. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:320-35

4. Sakuma S, Raices M, Borlido J, Guglielmi V, Zhu EYS, D'Angelo MA. Inhibition of nuclear pore complex formation selectively induces cancer cell death. Cancer Discov. 2021;11:176-93

5. Wang Z, Zhang J, Luo L, Zhang C, Huang X, Liu S. et al. Nucleoporin 93 regulates cancer cell growth and stemness in bladder cancer via Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Mol Biotechnol. 2025;67:2072-84

6. Lin CS, Liang Y, Su SG, Zheng YL, Yang X, Jiang N. et al. Nucleoporin 93 mediates β-catenin nuclear import to promote hepatocellular carcinoma progression and metastasis. Cancer Lett. 2022;526:236-47

7. Zhu X, Huang G, Zeng C, Zhan X, Liang K, Xu Q. et al. Structure of the cytoplasmic ring of the Xenopus laevis nuclear pore complex. Science. 2022;376:eabl8280

8. Dultz E, Ellenberg J. Live imaging of single nuclear pores reveals unique assembly kinetics and mechanism in interphase. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:15-22

9. Hazawa M, Lin DC, Kobayashi A, Jiang YY, Xu L, Dewi FRP. et al. ROCK-dependent phosphorylation of NUP62 regulates p63 nuclear transport and squamous cell carcinoma proliferation. EMBO Rep. 2018;19:73-88

10. Li F, Zhang Y, Li J, Jiang R, Ci S. NUP98-p65 complex regulates DNA repair to maintain glioblastoma stem cells. FASEB J. 2025;39:e70401

11. Chen L, He Y, Duan M, Yang T, Chen Y, Wang B. et al. Exploring NUP62's role in cancer progression, tumor immunity, and treatment response: insights from multi-omics analysis. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1559396

12. Nataraj NB, Noronha A, Lee JS, Ghosh S, Mohan Raju HR, Sekar A. et al. Nucleoporin-93 reveals a common feature of aggressive breast cancers: robust nucleocytoplasmic transport of transcription factors. Cell Rep. 2022;38:110418

13. Ouyang X, Hao X, Liu S, Hu J, Hu L. Expression of Nup93 is associated with the proliferation, migration and invasion capacity of cervical cancer cells. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. 2019;51:1276-85

14. Borrow J, Shearman AM, Stanton VP Jr, Becher R, Collins T, Williams AJ. et al. The t(7;11)(p15;p15) translocation in acute myeloid leukaemia fuses the genes for nucleoporin NUP98 and class I homeoprotein HOXA9. Nat Genet. 1996;12:159-67

15. Li D, Song H, Mei H, Fang E, Wang X, Yang F. et al. Armadillo repeat containing 12 promotes neuroblastoma progression through interaction with retinoblastoma binding protein 4. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2829

16. Wang J, Hong M, Cheng Y, Wang X, Li D, Chen G. et al. Targeting c-Myc transactivation by LMNA inhibits tRNA processing essential for malate-aspartate shuttle and tumour progression. Clin Transl Med. 2024;14:e1680

17. Li H, Yang F, Hu A, Wang X, Fang E, Chen Y. et al. Therapeutic targeting of circ-CUX1/EWSR1/MAZ axis inhibits glycolysis and neuroblastoma progression. EMBO Mol Med. 2019;11:e10835

18. Wang J, Wang X, Yang C, Li Q, Li D, Du X. et al. circE2F1-encoded peptide inhibits circadian machinery essential for nucleotide biosynthesis and tumor progression via repressing SPIB/E2F1 axis. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;280:135698

19. Hu A, Chen G, Bao B, Guo Y, Li D, Wang X. et al. Therapeutic targeting of CNBP phase separation inhibits ribosome biogenesis and neuroblastoma progression via modulating SWI/SNF complex activity. Clin Transl Med. 2023;13:e1235

20. Wang X, Guo Y, Chen G, Fang E, Wang J, Li Q. et al. Therapeutic targeting of FUBP3 phase separation by GATA2-AS1 inhibits malate-aspartate shuttle and neuroblastoma progression via modulating SUZ12 activity. Oncogene. 2023;42:2673-87

21. Li H, Jiao W, Song J, Wang J, Chen G, Li D. et al. circ-hnRNPU inhibits NONO-mediated c-Myc transactivation and mRNA stabilization essential for glycosylation and cancer progression. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2023;42:313

22. Yang C, Qu J, Cheng Y, Tian M, Wang Z, Wang X. et al. YY1 drives PARP1 expression essential for PARylation of NONO in mRNA maturation during neuroblastoma progression. J Transl Med. 2024;22:1153

23. Bao B, Tian M, Wang X, Yang C, Qu J, Zhou S. et al. SNORA37/CMTR1/ELAVL1 feedback loop drives gastric cancer progression via facilitating CD44 alternative splicing. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2025;44:15

24. Aykut B, Pushalkar S, Chen R, Li Q, Abengozar R, Kim JI. et al. The fungal mycobiome promotes pancreatic oncogenesis via activation of MBL. Nature. 2019;574:264-67

25. Alam A, Comer S, Levanduski E, Dey P. Fungal ablation and transplantation of specific fungal species into PDAC tumor-bearing mice. STAR Protoc. 2022;3:101644

26. Ito T, Ando H, Suzuki T, Ogura T, Hotta K, Imamura Y. et al. Identification of a primary target of thalidomide teratogenicity. Science. 2010;327:1345-50

27. Wu T, Hornsby M, Zhu L, Yu JC, Shokat KM, Gestwicki JE. Protocol for performing and optimizing differential scanning fluorimetry experiments. STAR Protoc. 2023;4:102688

28. Li D, Mei H, Pu J, Xiang X, Zhao X, Qu H. et al. Intelectin 1 suppresses the growth, invasion and metastasis of neuroblastoma cells through up-regulation of N-myc downstream regulated gene 2. Mol Cancer. 2015;14:47

29. Tao L, Moreno-Smith M, Ibarra-García-Padilla R, Milazzo G, Drolet NA, Hernandez BE. et al. CHAF1A blocks neuronal differentiation and promotes neuroblastoma oncogenesis via metabolic reprogramming. Adv Sci. 2021;8:e2005047

30. Xue B, Dunbrack RL, Williams RW, Dunker AK, Uversky VN. PONDR-FIT: a meta-predictor of intrinsically disordered amino acids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804:996-1010

31. Ulianov SV, Velichko AK, Magnitov MD, Luzhin AV, Golov AK, Ovsyannikova N. et al. Suppression of liquid-liquid phase separation by 1,6-hexanediol partially compromises the 3D genome organization in living cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:10524-41

32. Huang J, Zheng W, Zhang P, Lin Q, Chen Z, Xuan J. et al. ChIPBase v3.0: the encyclopedia of transcriptional regulations of non-coding RNAs and protein-coding genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51:D46-56

33. Rahman MM, Tollefsbol TO. Targeting cancer epigenetics with CRISPR-dCAS9: Principles and prospects. Methods. 2021;187:77-91

34. Preet R, Islam MA, Shim J, Rajendran G, Mitra A, Vishwakarma V. et al. Gut commensal Bifidobacterium-derived extracellular vesicles modulate the therapeutic effects of anti-PD-1 in lung cancer. Nat Commun. 2025;16:3500

35. Catrow JL, Zhang Y, Zhang M, Ji H. Discovery of selective small-molecule inhibitors for the β-catenin/T-cell factor protein-protein interaction through the optimization of the acyl hydrazone moiety. J Med Chem. 2015;58:4678-92

36. Hylton-McComas HM, Cordes A, Floros KV, Faber A, Drapkin BJ, Miles WO. Myc family proteins: Molecular drivers of tumorigenesis and resistance in neuroendocrine tumors. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2025;1880:189332

37. Sabò A, Amati B. Genome recognition by MYC. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4:a014191

38. Peifer M, Fernández-Cuesta L, Sos ML, George J, Seidel D, Kasper LH. et al. Integrative genome analyses identify key somatic driver mutations of small-cell lung cancer. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1104-10

39. Liu H, Tang X, Srivastava A, Pécot T, Daniel P, Hemmelgarn B. et al. Redeployment of Myc and E2f1-3 drives Rb-deficient cell cycles. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:1036-48

40. Leung JY, Ehmann GL, Giangrande PH, Nevins JR. A role for Myc in facilitating transcription activation by E2F1. Oncogene. 2008;27:4172-79

41. Miller DM, Thomas SD, Islam A, Muench D, Sedoris K. c-Myc and cancer metabolism. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:5546-53

42. Arabi A, Wu S, Ridderstråle K, Bierhoff H, Shiue C, Fatyol K. et al. c-Myc associates with ribosomal DNA and activates RNA polymerase I transcription. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:303-10

43. Poortinga G, Hannan KM, Snelling H, Walkley CR, Jenkins A, Sharkey K. et al. MAD1 and c-MYC regulate UBF and rDNA transcription during granulocyte differentiation. EMBO J. 2004;23:3325-35

44. Kalkat M, Resetca D, Lourenco C, Chan PK, Wei Y, Shiah YJ. et al. MYC protein interactome profiling reveals functionally distinct regions that cooperate to drive tumorigenesis. Mol Cell. 2018;72:836-48

45. Delmore JE, Issa GC, Lemieux ME, Rahl PB, Shi J, Jacobs HM. et al. BET bromodomain inhibition as a therapeutic strategy to target c-Myc. Cell. 2011;146:904-17

46. Han H, Jain AD, Truica MI, Izquierdo-Ferrer J, Anker JF, Lysy B. et al. Small-molecule MYC inhibitors suppress tumor growth and enhance immunotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2019;36:483-97

47. Beaulieu ME, Jauset T, Massó-Vallés D, Martínez-Martín S, Rahl P, Maltais L. et al. Intrinsic cell-penetrating activity propels Omomyc from proof of concept to viable anti-MYC therapy. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11:eaar5012

48. Casey SC, Tong L, Li Y, Do R, Walz S, Fitzgerald KN. et al. MYC regulates the antitumor immune response through CD47 and PD-L1. Science. 2016;352:227-31

49. Peifer M, Berg S, Reynolds AB. A repeating amino acid motif shared by proteins with diverse cellular roles. Cell. 1994;76:789-91

50. Shimada K, Park S, Miyata H, Yu Z, Morohoshi A, Oura S. et al. ARMC12 regulates spatiotemporal mitochondrial dynamics during spermiogenesis and is required for male fertility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118:e2018355118

51. Huang Y, Jiang Z, Gao X, Luo P, Jiang X. ARMC subfamily: Structures, functions, evolutions, interactions, and diseases. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8:791597

52. Narunsky-Haziza L, Sepich-Poore GD, Livyatan I, Asraf O, Martino C, Nejman D. et al. Pan-cancer analyses reveal cancer-type-specific fungal ecologies and bacteriome interactions. Cell. 2022;185:3789-806

53. Liu MM, Zhu HH, Bai J, Tian ZY, Zhao YJ, Boekhout T. et al. Breast cancer colonization by Malassezia globosa accelerates tumor growth. mBio. 2024;15:e0199324

54. Zhang Z, Qiu Y, Feng H, Huang D, Weng B, Xu Z. et al. Identification of Malassezia globosa as a gastric fungus associated with PD-L1 expression and overall survival of patients with gastric cancer. J Immunol Res. 2022;2022:2430759