13.3

Impact Factor

Theranostics 2026; 16(7):3408-3425. doi:10.7150/thno.124303 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Nanobody Nb07 mitigates sepsis by blocking the PFKM-p53-PD-1 axis to enhance macrophage phagocytosis

1. Jiangsu International Laboratory of Immunity and Metabolism, Jiangsu Province Key Laboratory of Immunity and Metabolism, Department of Pathogenic Biology and Immunology, Xuzhou Medical University, Xuzhou 221004, Jiangsu, China.

2. National Demonstration Center for Experimental Basic Medical Science Education, Xuzhou Medical University, Xuzhou 221004, Jiangsu, China.

3. Department of Clinical Laboratory, Affiliated Jinhua Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine, Jinhua 310058, Zhejiang, China.

4. Public Experimental Research Center, Xuzhou Medical University, Xuzhou 221004, Jiangsu, China.

5. Department of Infectious Disease, The Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University, Xuzhou Medical University, Xuzhou 221004, Jiangsu, China.

Received 2025-8-27; Accepted 2025-12-10; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

Rationale: Macrophage phagocytosis is essential for pathogen clearance during sepsis. We previously demonstrated that the glycolytic enzyme 6-phosphofructokinase, muscle type (PFKM), modulates macrophage functions and its deficiency alleviates sepsis in mice. However, the function of PFKM in regulating macrophage phagocytosis remains unclear.

Methods: CD14+ monocytes were sorted by flow cytometry from healthy volunteers and septic patients, and the subcellular localization of PFKM was assessed by immunofluorescence. Nuclear translocation mechanisms and PFKM-p53 interaction were identified by Co-immunoprecipitation coupled with mass spectrometry (Co-IP/MS) and validated by Co-IP. Transcriptomic sequencing was used to identify the downstream target of the PFKM-p53 complex. Inflammatory cytokine levels were detected by ELISA and real-time RT-PCR, and the phagocytosis of macrophages was assessed by flow cytometry. Dual-luciferase reporter assays and ChIP were employed to investigate whether PFKM acts as a co-regulator of p53 in mediating Pdcd1 transcription. Nanobodies targeting PFKM-p53 were screened and subsequently synthesized according to the sequences. The effect of nuclear PFKM and the therapeutic effect of nanobodies were evaluated on the well-established sepsis mouse models induced by Escherichia coli or cecal ligation and puncture.

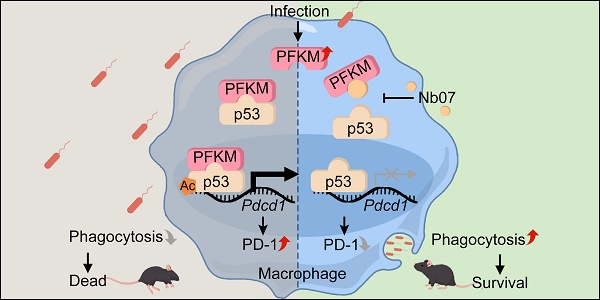

Results: PFKM translocated to the macrophage nucleus during sepsis. Nuclear accumulation of PFKM impaired phagocytosis through a non-glycolytic “moonlighting” function and exacerbated sepsis. Mechanistically, PFKM interacts with p53, which facilitates its nuclear translocation. Subsequently, PFKM promotes p53 acetylation at K120, enhancing p53 binding to the Pdcd1 promoter and driving its transcription, thereby suppressing macrophage phagocytosis. Blocking the PFKM-p53 interaction with a nanobody, Nb07, restored phagocytosis of macrophages and alleviated sepsis in mice.

Conclusion: Our data reveal the PFKM-p53-PD-1 axis that suppresses macrophage phagocytosis in sepsis and highlight the therapeutic potential of targeting this pathway with nanobody-based strategies.

Keywords: sepsis, PFKM, moonlighting function, macrophage, phagocytosis

Introduction

Sepsis is one of the adverse clinical outcomes characterized as life-threatening organ dysfunction [1], posing a major global socioeconomic burden [2,3]. During sepsis, macrophage phagocytosis is critical for pathogen clearance, tissue regeneration, and inflammation resolution [4]. Both macrophage deletion and phagocytosis dysfunction could exacerbate sepsis [5,6], while enhancing macrophage phagocytosis improves the survival and alleviates multi-organ injury in murine models [7,8]. However, infection can induce macrophage phagocytic dysfunction [9,10], and its underlying mechanisms remain unclear.

Macrophage functions, including phagocytosis, are closely related to glycolysis [11]. Emerging evidence indicates that properly modulating macrophage glycolysis could represent a promising strategy for sepsis [12,13]. Phosphofructokinase 1 (PFK1), the key rate-limiting enzyme modulating glycolysis [14], exists as cell-specific isoforms. We previously reported that the protein abundance of the muscle-type isoenzyme (PFKM) was higher than that of liver type (PFKL) and platelet type (PFKP) [15]. The PFKM protein level was elevated in mono-macrophages from septic patients, and PFKM knockout conferred protection against sepsis in mice [15]. Notably, although PFKM is conventionally regarded as a cytoplasmic protein (https://www.proteinatlas.org), we observed PFKM nuclear translocation in stimulated macrophages. Given the critical influence of subcellular localization on protein functions, the role of nuclear PFKM is indistinct.

While current research on PFKM primarily focuses on its canonical metabolic function, glycolytic enzymes exhibit non-canonical “moonlighting” functions [16]. For example, Pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) translocates to the nucleus [17], where it interacts with the transcription factors to enhance the expression of target genes [18]. Recent research has shown that PFKM stabilizes the target protein in glioblastoma cells [19]. Nevertheless, the potential for nuclear PFKM to exert moonlighting functions, specifically in macrophage phagocytosis, remains unexplored.

In this study, we investigated the role and underlying mechanisms of nuclear PFKM in regulating macrophage phagocytosis. Our data indicated that nuclear PFKM accumulation impaired macrophage phagocytosis by interacting with p53 and enhancing p53-mediated PD-1 expression. Furthermore, we developed a nanobody, Nb07, to block this specific interaction. Nb07 treatment restored macrophage phagocytosis and alleviated sepsis in mice, which provides a potential therapeutic strategy for sepsis.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) (O127:B8, Sigma), macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) (APA090Mu61, Cloud-Clone Corp), 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) (F0101-5G, BOSF), and anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody (BE0273, Bio X Cell) were prepared in PBS (BC-BPBS-01, Bio-Channel). C646 (p300/CBP inhibitor, HY-13823, MCE), DOX (HY-N0565, MCE), fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (F104848-1g, Aladdin), Ivermectin (IVM) (importin inhibitor, HY-15310, MCE), and MG149 (Tip60 inhibitor, HY-15887, MCE) were prepared in DMSO.

Patient samples

Peripheral blood samples (n = 5) were obtained as described [15] with the approval of the Ethics Committee of Xuzhou Medical University (XYFY2022-KL442-01).

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from GemPharmatech Co, Ltd (N000013). Homozygote Pfkmf/f; LyzCre/+ mice were obtained as described [15]. The p53 knockout mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (JAX: 002101).

All mice were maintained under SPF conditions with a 12 h light/dark cycle and provided with a standard diet (1002, Pizhou Xiaohe Technology Development Co, Ltd) and water ad libitum, with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Xuzhou Medical University (202303T015).

Sepsis models

For the Escherichia coli (E. coli)-induced sepsis model, C57BL/6, Pfkmf/+ or Pfkmf/f; LyzCre/+ mice (8-10 weeks old) were injected intraperitoneally with 3-5 × 10⁷ CFU clinical E. coli [7].

LPS-induced sepsis model and cecal ligation and puncture (CLP)-induced sepsis model were performed as previously described [15].

To overexpress nuclear PFKM in macrophages in vivo, the Pfkmf/+ or Pfkmf/f; LyzCre/+ mice (8-10 weeks old) were intravenously injected with adeno-associated virus (AAV9-NLS-PFKM-3×Flag, Zebrafish Biotechnology Co, Ltd.) at a dose of 1 × 1011 VG/mouse.

For Nb07 treatment, mice were injected with 1 mg/kg Nb07 intraperitoneally 2 h before or 6 h after modeling. Mice intraperitoneally injected with PBS (BC-BPBS-01, Bio-Channel) served as the control group. Mortality was monitored and recorded daily following the injection.

Cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMNCs) were isolated with Percoll (17-0891-02, GE HealthCare) following the manufacturer's instructions. HEK-293T cells (FH0244) and RAW264.7 (FH0328) were obtained from FuHeng Cell Center and cultured in DMEM (KGL1206-500, Keygen) with 10% FBS (#3022A, Umedium, Hefei, China).

Bone marrow cells were harvested from the femurs and tibias of mice. The bone marrow cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS and 20 ng/mL M-CSF (APA090Mu61, Cloud-Clone Corp) for 4 days to obtain bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs). The abdominal cavity was lavaged with PBS to obtain peritoneal macrophages. All cells were maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO₂.

Western blotting

Western blotting was carried out as described [15]. Briefly, the cells were lysed using RIPA lysis buffer (P0013C, Beyotime) and then separated by 8% SDS-PAGE. The proteins were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (B500, Abm). Antibodies are listed in Table S1. Images were obtained using an ECL system (BIO-RAD) and analyzed by Image Lab.

RNA extraction and real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol Reagent (15596026, Invitrogen™) and reverse-transcribed to cDNA with 5 × All-In-One RT MasterMix (G490, Abm). Real-time RT-PCR was performed as described [15]. Gene expression was calculated using the 2-△△Ct method with Actb as the internal control. Primer sequences are listed in Table S2.

Transcriptomic sequencing

RAW264.7 overexpressing nuclear PFKM were treated with or without 600 ng/mL DOX for 48 h. Then, the total RNA from these two groups (n = 3) was extracted as described above. The RNA samples were submitted to Majorbio (Shanghai, China) for mRNA enrichment, purification, and subsequent transcriptomic sequencing. The data were analyzed by the Majorbio platform (www.majorbio.com/tools).

Multiple immunofluorescence staining

Fixed cells and tissue sections were stained with the indicated antibodies (Table S1) using the PANO6-plex IHC kit (TSA-Rab, 0081100100, Panovue) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Fluorescent images were captured using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica STELLARIS 5, Germany).

The nuclear translocation ratio was quantified for each sample by analyzing three randomly selected fields of view. The nuclear translocation ratio was calculated as the proportion of CD14+ or F4/80+ cells exhibiting nuclear PFKM localization among the total number of respective cells per field. The results from five samples per group are presented as the mean of the three field measurements.

Histology analysis

Lung tissues were fixed in 4% PFA (VIH100, VICMED) for over 24 h, followed by dehydration, embedding, sectioning, and hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) staining for histological examination. Score the alveolar wall thickness, lung tissue damage, and inflammatory cell infiltration on a 5-point scale (0 = minimal injury, 1 = mild injury, 2 = moderate injury, 3 = severe injury, 4 = maximum injury). The sum of these scores determines the severity of lung injury.

Bacterial load determination

The peritoneal cavity was flushed with 5 mL PBS to obtain peritoneal lavage fluid. Peripheral blood was collected from the orbital venous plexus and diluted 1:50 in PBS. All samples were plated onto LB agar plates (VIC454, VICMED) and incubated at 37 °C for 18 h.

Biochemical analysis

IL-6 (1210602, Dakewe) and TNF-α (430904, BioLegend) levels were measured using ELISA according to the manufacturer's protocols.

Lactate measurement

Cell supernatants were collected when cells reached 70-80% confluence. Lactate levels were measured using the Lactate Assay Kit (KGA7402, KeyGEN). The lactate concentration was calculated with the formula: (sample-blank)/(standard-blank) × standard concentration × dilution factor.

Cytometric bead array (CBA)

Cytokine concentrations were measured using the LEGENDplex™ CBA kit (740446, BioLegend) according to the manufacturer's protocols. In brief, the samples were incubated with beads and determined by flow cytometry. Data were analyzed using LEGENDplex™ data analysis software (v8.0).

Co-immunoprecipitation

Co-IP was performed as described previously [20]. Briefly, cells were lysed using RIPA lysis buffer, then incubated with the appropriate antibodies overnight, followed by incubation with Protein A/G agarose beads (20334 & 20399, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for another 2 h at 4 °C. The beads were washed, and the proteins were eluted by boiling in 1 × SDS-PAGE protein loading buffer (20315ES, YEASEN). The eluted proteins were determined by Western blotting. Detailed antibody information is provided in Table S1.

Nuclear and cytoplasmic separation

Cells were fractionated into cytoplasmic and nuclear components using the Proteintech kit (PK10014, Proteintech) according to the manufacturer's protocols. After centrifugation, the supernatant containing cytoplasmic proteins and the pellet containing nuclear proteins were harvested for Western blotting.

Dual-luciferase reporter assay

For dual-luciferase reporter assays, HEK-293T cells were co-transfected with a Pdcd1 promoter-driven firefly luciferase plasmid, the Renilla luciferase control plasmid-pRL-TK (D2690, Beyotime), and expression vectors or empty controls using jetPRIME® transfection reagent (0000004162, Polyplus). Firefly luciferase activity was measured with the Bio-LumiTM kit (RG029s, Beyotime) and normalized to Renilla luciferase activity to account for transfection efficiency.

Flow cytometry

Cells were harvested and washed twice with cold PBS. Then, cells were incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies for 30 min at 4 °C (Table S1). Afterwards, cells were detected by BD FACSCantoTM II flow cytometer and analyzed using FlowJo software.

Screening and synthesis of nanobodies

First, the interacting sites between PFKM and p53 were predicted through AlphaFold3-based structural modeling. Subsequently, 300 novel peptide binders were designed de novo to mimic CDR3 regions using RFdiffusion. Then, binders were screened via HDock molecular docking, grafted onto a nanobody scaffold, and generated variant nanobodies by computational mutagenesis. High-affinity nanobodies targeting the PFKM protein were screened by Hefei Kejing Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Finally, through one-to-one comparison by AlphaFold3, the nanobodies (Nb07, Nb15, Nb51) that could completely occupy most of the PFKM-p53 binding sites were synthesized by Biointron Biotechnology Inc.

Synthesis of Nb07-FITC

First, Nb07 (10 mg) and FITC (1 mg, F104848, Aladdin) were added to a tube containing 2 mL PBS. The mixture was stirred overnight at 4 °C and then dialyzed against 4 L of ddH2O in a 500 Da MWCO (MD34-500, VICMED) for two days to remove the unreacted FITC. The products were dried and dissolved in PBS to obtain the fluorescent nanobody.

Cell viability

Cells were seeded into 96-well plates at 104 cells/well and treated with different concentrations of Nb07. After 24 h, 10 µL Cell Counting Kit-8 (C6005, NCM) was added to each well and incubated for 30 min. The absorbance values at 450 nm were detected by the Synergy2 Multimode Microplate Reader.

Bacterial phagocytosis assay

The phagocytosis assay was performed by pHrodo™ iFL Red or Green STP Ester (P36010 and P36012, Thermo Fisher) according to instructions as described previously [21]. Briefly, E. coli were labeled with pHrodo and then co-cultured with macrophages at an MOI of 20:1 for 1 h at 37 °C. Subsequently, cells were washed 3 times with PBS, and phagocytosis was analyzed by flow cytometry (BD FACSCanto™ II). Data were analyzed using FlowJo software.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

The binding sites of p53 on the Pdcd1 promoter were predicted by Transcription Factor Affinity Prediction (TRAP 3.05). ChIP was performed using the BeyoChIP™ ChIP assay kit with Protein A/G Magnetic Beads (P2080S, Beyotime) according to the manufacturer's instructions as described [22]. Immunoprecipitation of cross-linked chromatin was conducted with antibodies (Table S1). The purified DNA was amplified by real-time PCR using primers listed in Table S3.

Plasmid, siRNAs, lentivirus, and transfection

The nuclear localization signal (NLS)-PFKM and PD-1 overexpression plasmids were constructed by cloning the respective cDNAs into the pLVX-TetOne-Puro vector, which was kindly provided by Professor Feng Guo (Xuzhou Medical University). Subsequently, lentiviruses were constructed, and stable cell lines were established following standard protocols [23]. Additionally, PFKM, NLS-PFKM, p53, or Nb07 cDNAs were amplified and cloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector. The shRNA plasmids targeting p53 (shp53#1 and shp53#2) were gifts from Professor Jiehui Di (Xuzhou Medical University). The siRNAs against PD-1 and p53 were purchased from HyCyteTM (Suzhou, China). The adeno-associated virus (AAV) for nuclear PFKM overexpression in mouse macrophages was procured from Zebrafish Biotech (Nanjing, China).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as Mean ± SD. Survival curve data are presented as a Kaplan-Meier plot, with a log-rank test used to compare susceptibility between the different groups. One-way ANOVA was applied for multi-group comparisons, and t-tests for two-group comparisons. Two-way ANOVA was applied for two-factor comparisons. Experiments were performed at least twice. The number of mice or samples per group (replicates of independent experiments) and statistical tests are shown in the Figure legends. Statistical differences were defined as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, analyzed by GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software Inc.).

Results

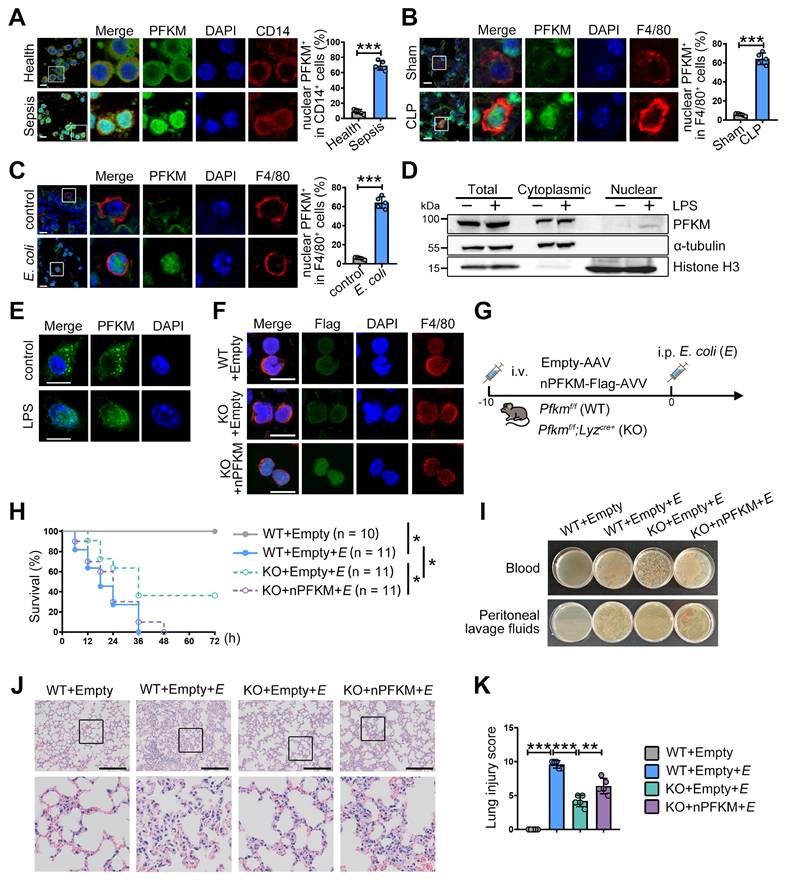

Nuclear accumulation of PFKM in macrophages exacerbates sepsis

Consistent with our previous study [15], CD14+ monocytes from septic patients exhibited elevated PFKM protein levels (Figure 1A). Moreover, nuclear translocation of PFKM was detected in approximately 65% of CD14+ cells from septic patients (Figure 1A). To confirm this, we examined PFKM sub-localization in well-established sepsis mouse models induced by CLP operation or E. coli injection. In both models, nuclear accumulation of PFKM occurred in F4/80⁺ macrophages within the lungs (Figure 1B-C, Movie S1-4). Furthermore, in vitro experiments validated that LPS stimulation triggered nuclear PFKM accumulation in BMDMs (Figure 1D-E).

To assess the impact of PFKM nuclear accumulation in macrophages during sepsis, we used myeloid-specific PFKM knockout mice (Pfkmf/f; Lyzcre+, KO). These mice were intravenously injected with adeno-associated virus to overexpress the nuclear PFKM specifically in macrophages (Figure 1F), followed by injection with E. coli to induce sepsis (Figure 1G). PFKM knockout improved survival rates (Figure 1H), reduced bacterial loads in blood and peritoneal fluid (Figure 1I), and attenuated lung tissue injury (Figure 1J-K). Conversely, nuclear PFKM overexpression in macrophages exacerbated sepsis development and reversed these protective effects (Figure 1H-K). Collectively, these data indicate that nuclear PFKM enrichment in macrophages promotes sepsis progression, and PFKM nuclear translocation in macrophages could be a risk factor for sepsis.

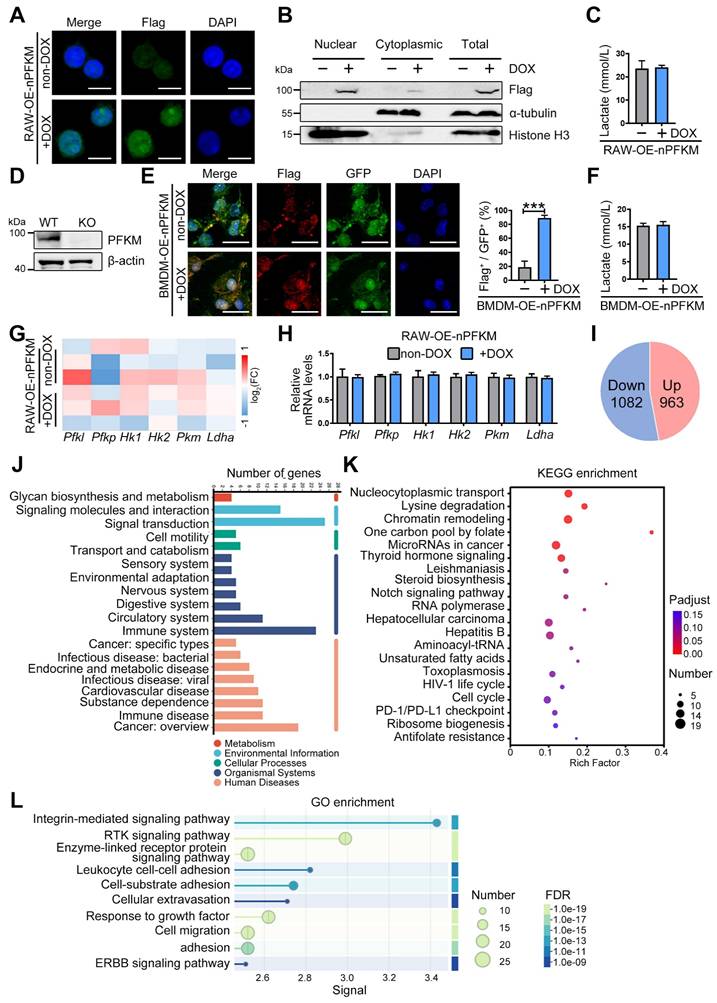

Nuclear PFKM accumulation alters macrophage gene profile

Although PFKM is a rate-limiting enzyme in glycolysis, ectopic expression of nuclear PFKM in the macrophage cell line RAW264.7 cells (RAW-OE-nPFKM) did not alter glycolytic activity as expectedly (Figure 2A-C). To validate this, we isolated BMDMs from Pfkmf/f; Lyzcre+ mice (Figure 2D). Nuclear PFKM overexpression also barely affected the lactate levels of BMDMs (Figure 2E-F). Then, we performed transcriptomic sequencing to investigate the gene expression profile in macrophages with ectopic expression of nuclear PFKM. Consistent with the in vitro experiment, the mRNA expression of key glycolytic enzymes, including Pfk1, Pfkp, Hk1, Hk2, Pkm, and Ldha, remained stable after ectopically expressed nuclear PFKM (Figure 2G-H). Our results demonstrate that nuclear PFKM could mediate macrophage function in a glycolysis-independent manner.

Reactome analysis based on transcriptomic sequencing indicated that the signal transduction and the immune system were enriched (Figure 2J). Up-regulated signals in macrophages overexpressing nuclear PFKM (Figure 2I) were analyzed using the KEGG pathway database. Data showed that the nucleocytoplasmic transport, chromatin remodeling, and PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint that influence phagocytosis [24,25] were enriched (Figure 2K). In addition, GO enrichment analysis highlighted the signaling pathways associated with macrophage phagocytosis (Figure 2L), suggesting that nuclear PFKM could affect phagocytosis of macrophages.

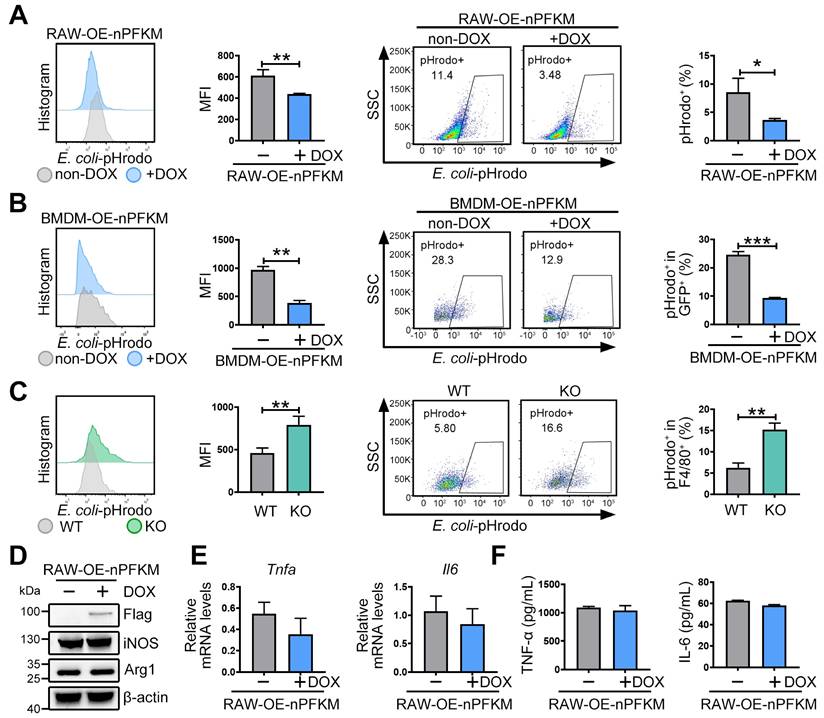

Nuclear PFKM overexpression impairs macrophage phagocytosis

To validate whether nuclear PFKM could regulate the macrophage phagocytosis, E. coli was labeled with pHrodo and then co-cultured with macrophages. Ectopic expression of nuclear PFKM suppressed bacterial phagocytosis in RAW264.7 cells (Figure 3A). Similarly, overexpression of nuclear PFKM impaired BMDM phagocytosis (Figure 3B), while Pfkm deficiency enhanced the bacterial phagocytosis (Figure 3C). Notably, without additional stimulation, nuclear PFKM overexpression did not affect the levels of molecules involved in macrophage polarization (Figure 3D) or inflammatory cytokine production (Figure 3E-F, Figure S1). Collectively, our results confirm that nuclear PFKM mainly regulates phagocytosis in macrophages.

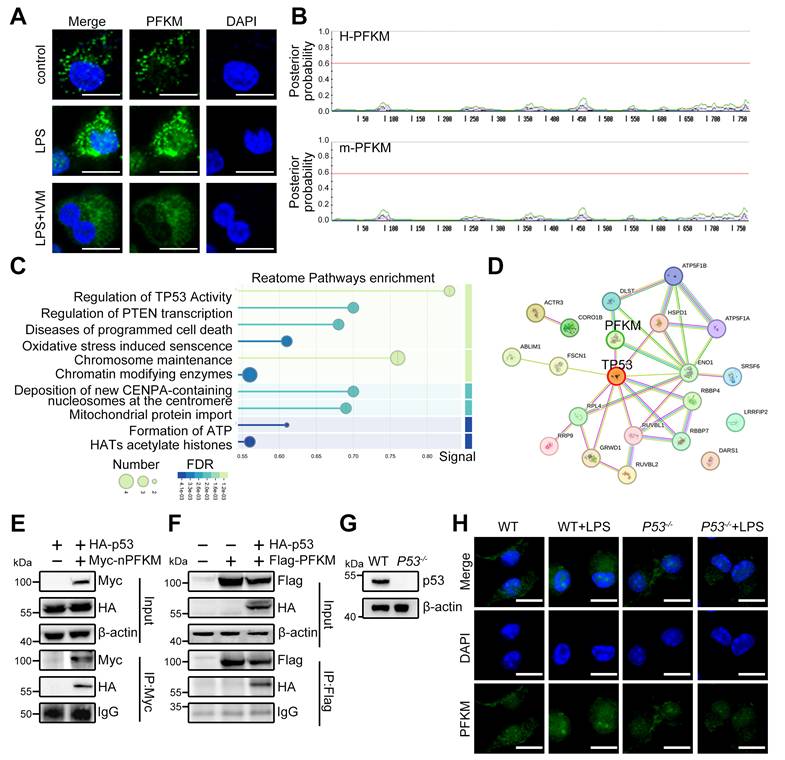

Nuclear translocation of PFKM is dependent on p53

PFKM is mainly localized to the cytoplasm in cells without stimulation (https://www.proteinatlas.org), yet how PFKM translocates into the nucleus remains unknown. Nuclear import of most proteins necessitates an NLS for specific recognition and transport by importins [26,27]. The importin inhibitor IVM reduced LPS-induced nuclear PFKM accumulation (Figure 4A). However, no NLS was predicted in PFKM according to its amino acid sequence (Figure 4B), demonstrating that PFKM could be indirectly shuttled into the nucleus via other protein(s) containing NLS.

PFKM accumulating in macrophage nuclei exacerbates sepsis. (A-C) The nuclear translocation ratio of PFKM in CD14+ or F4/80+ cells was quantified as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Representative multiplex immunofluorescent staining of PBMNCs isolated from healthy volunteers and septic patients (n = 5). Scale bars, 10 µm. (B) Sepsis was induced by CLP in wild-type (WT) mice. Representative multiplex immunofluorescent staining of lungs was obtained at 24 h post-CLP (n = 5). Scale bars, 10 µm. (C) WT mice were injected with E. coli (3 × 10⁷ CFU/mouse) intraperitoneally. Representative lung immunofluorescence images at 24 h post-injection (n = 5). Scale bars, 10 µm. (D-E) BMDMs from WT mice were stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL) for 96 h, and the subcellular localization of PFKM was detected by (D) Western blotting of cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions and (E) immunofluorescence. Scale bars, 10 µm. (F) The indicated mouse strains were intravenously injected with adenoviruses (1 × 1011 VG/mouse) for 10 days, and representative multiplex immunofluorescent staining of peritoneal macrophages is shown. Scale bars, 10 µm. (G) A schematic diagram shows the overexpression of nuclear PFKM (nPFKM) in macrophages, followed by intraperitoneal injection of E. coli (E) (5 × 10⁷ CFU/mouse) to induce sepsis in mice. (H) Survival curves of mice were recorded (n = 10-11). (I) Representative photos of plated blood and peritoneal lavage fluid from mice at 3 h after infection (n = 3). (J) Representative H & E staining of lungs at 24 h post-injection (n = 5). Scale bars, 200 µm. (K) Histological injury of the lungs was scored (n = 5). Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired t-test for (A, B, and C), by Mantel-Cox's log-rank test for (H), and by one-way ANOVA for (K). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Overexpressing nuclear PFKM affects the gene profile of macrophages but not glycolysis. (A-C) The RAW-OE-nPFKM cells were established and treated with or without DOX (600 ng/mL) for 48 h. (A) Representative multiplex immunofluorescent staining and (B) Western blotting analysis was utilized to detect the nuclear PFKM levels. Scale bars, 10 µm. (C) Lactate levels in the culture medium of cells were detected by the Lactate Assay Kit. (D) Western blotting analysis was utilized to detect the PFKM expression in BMDMs. (E) BMDMs from KO mice were infected with both nuclear PFKM and GFP lentivirus, followed by DOX (600 ng/mL) treatment for 48 h. GFP+ cells were sorted by flow cytometry. Representative immunofluorescence staining. Statistical data of the proportion of Flag+ cells among GFP+ cells. Scale bars, 10 µm. (F) Lactate levels in the culture medium of cells were measured by the Lactate Assay Kit. (G) Heatmap analysis of the key glycolytic kinases and lactate dehydrogenase. (H) mRNA expressions of the glycolytic enzymes were detected by real-time RT-PCR. (I) The number of up-regulated and down-regulated genes in transcriptomic sequencing. (J) Reactome analysis of all differentially expressed genes. (K) KEGG enrichment analysis of upregulated genes. (L) GO enrichment analysis of upregulated genes. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired t-test for (C, E, F, and H). *** P < 0.001.

The effect of nuclear PFKM on macrophage function. (A) RAW-OE-nPFKM cells were treated with or without DOX (600 ng/mL) for 48 h, and then co-cultured with E. coli-pHrodo for 1 h. Phagocytosis was assessed by flow cytometry. (B) BMDMs from KO mice were infected with nuclear PFKM lentivirus and followed by treatment with or without DOX (600 ng/mL) for 48 h, and then co-cultured with E. coli-pHrodo for 1 h. Phagocytosis was assessed by flow cytometry. (C) Peritoneal macrophages from WT or KO mice were co-cultured with E. coli-pHrodo for 1 h, and phagocytosis was assessed by flow cytometry. (D-F) RAW-OE-nPFKM cells were treated with or without DOX (600 ng/mL) for 48 h. (D) The protein levels of iNOS and Arg-1 were assessed by Western blotting analysis. (E) The mRNA levels of Tnfa and Il6 were measured by real-time RT-PCR. (F) The levels of TNF-α and IL-6 in the culture medium were detected using ELISA. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired t-test for (A, B, C, E and F). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

To further validate whether the translocation of PFKM depends on binding to a protein containing NLS, Co-IP/MS was performed and identified p53 as the primary carrier candidate (Figure 4C), a famous protein known to harbor a canonical NLS [28]. The STRING database predicted the interaction between PFKM and p53 (Figure 4D). Furthermore, Co-IP also confirmed that PFKM can bind to p53 (Figure 4E-F), and immunofluorescence demonstrated their nuclear co-localization in septic macrophages (Figure S2, Movie S5-6). Moreover, we treated BMDM from P53-/- mice (Figure 4G) with LPS, and found that the nuclear accumulation of PFKM was abolished in p53-deficient BMDMs upon LPS stimulation (Figure 4H). Collectively, our data reveal that PFKM depends on binding to p53 for its nuclear import.

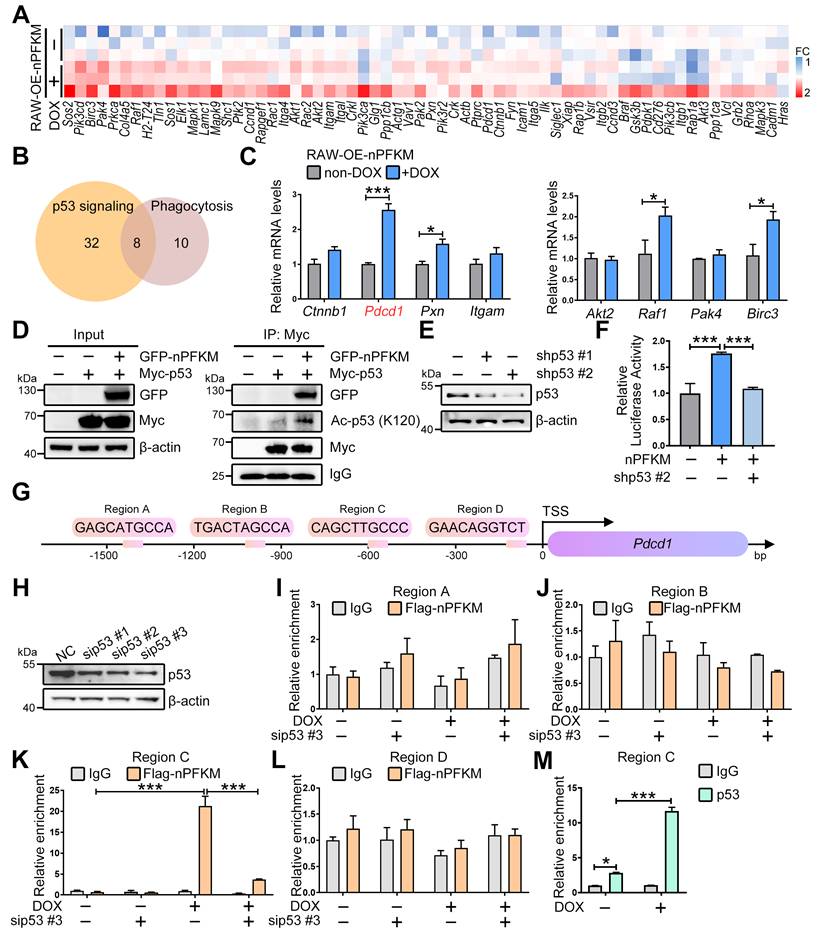

Nuclear PFKM promotes PD-1 expression by facilitating p53 acetylation

To elucidate the mechanism by which the PFKM-p53 axis suppresses macrophage phagocytosis, we analyzed our transcriptomic data and identified candidate downstream genes from the top Gene Ontology (GO) term (Figure 5A). Cross-referencing with the STRING database revealed 8 genes implicated in both p53 signaling and phagocytosis (Figure 5B). Among these, Pdcd1 was the most up-regulated upon nuclear PFKM overexpression (Figure 5C), suggesting that PD-1 could function as a key downstream of the PFKM-p53 axis in regulating phagocytosis.

A previous study demonstrated that acetyltransferases p300, CBP, and TIP60 facilitated p53-mediated Pdcd1 transcription via boosting p53 acetylation at K120 [29]. To investigate how nuclear PFKM orchestrates p53 to drive Pdcd1 transcription, we performed Co-IP and ChIP assays. Nuclear PFKM overexpression significantly enhanced p53-K120 acetylation (Figure 5D), while this enhancement was abolished upon inhibition of p300/CBP or TIP60 (Figure S3). ChIP assays demonstrated specific recruitment of the nuclear PFKM-p53 complex to a region ~0.6 kb upstream (Region C) of the Pdcd1 promoter (Figure 5G-M). The enrichment was strengthened by nuclear PFKM overexpression, while abrogated by p53 knockdown (Figure 5K). Consistently, overexpressing nuclear PFKM obviously boosted p53-mediated Pdcd1 transcription (Figure 5E-F). Collectively, our results indicate that nuclear PFKM binding facilitates the recruitment of acetyltransferases to enhance K120 acetylation of p53, thereby promoting p53 transcriptional activity at the Pdcd1 promoter.

p53 is crucial for the nuclear translocation of PFKM. (A) Representative immunofluorescent staining of PFKM in WT BMDMs treated with LPS (100 ng/mL) alone or combined with IVM (5 μM) for 96 h. Scale bars, 10 µm. (B) The NLStradamus was used to predict the nuclear localization sequence of PFKM (www.moseslab.csb.utoronto.ca/NLStradamus/). (C) Proteins interacting with PFKM were analyzed by LC-MS/MS. (D) The interaction between PFKM and p53 was predicted using the STRING protein interaction database (string-db.org). (E-F) Co-IP combined with Western blotting analysis was used to analyze the interaction of PFKM and p53. (G) Western blotting of p53 in BMDMs from WT and p53 knockout mice (P53-/-). (H) Representative immunofluorescent staining of BMDMs stimulated with or without LPS (100 ng/mL) for 96 h. Scale bars, 10 µm.

PFKM-p53 interaction induces PD-1. (A) Heatmap analysis of genes in the Integrin-mediated signaling pathway. (B) A Venn diagram shows the intersection of two gene sets: List1 (yellow) represents genes associated with the p53 signaling pathway; List2 (pink) includes genes related to macrophage phagocytosis. (C) Real-time RT-PCR shows mRNA expression levels of the 8 indicated genes. (D) Co-IP combined with Western Blotting shows the acetylation level of lysine 120 on p53. (E) HEK-293T cells were transfected with p53-targeting shRNA (shp53) for 24 h. The p53 level was determined by Western blotting. (F) Luciferase assay evaluates the transcriptional activity of Pdcd1 following nuclear PFKM overexpression and p53 knockdown. (G) Schematic diagram of the mouse Pdcd1 gene locus with four potential p53-binding regions. TSS, transcription start site. (H) RAW264.7 cells were transfected with p53-targeting siRNA (sip53) or negative control siRNA (NC) for 24 h. The p53 level was determined by Western blotting. (I-M) ChIP analysis of p53 occupancy on Pdcd1 promoter region in RAW-OE-nPFKM cells treated with or without DOX (600 ng/mL) for 48 h. Enrichment of the Pdcd1 promoter region was quantified by real-time PCR. (I-L) ChIP was performed with an anti-Flag antibody. (M) ChIP was performed with an anti-p53 antibody. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired t-test for (C), by one-way ANOVA for (F), and by two-way ANOVA for (I, J, K, L, and M). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

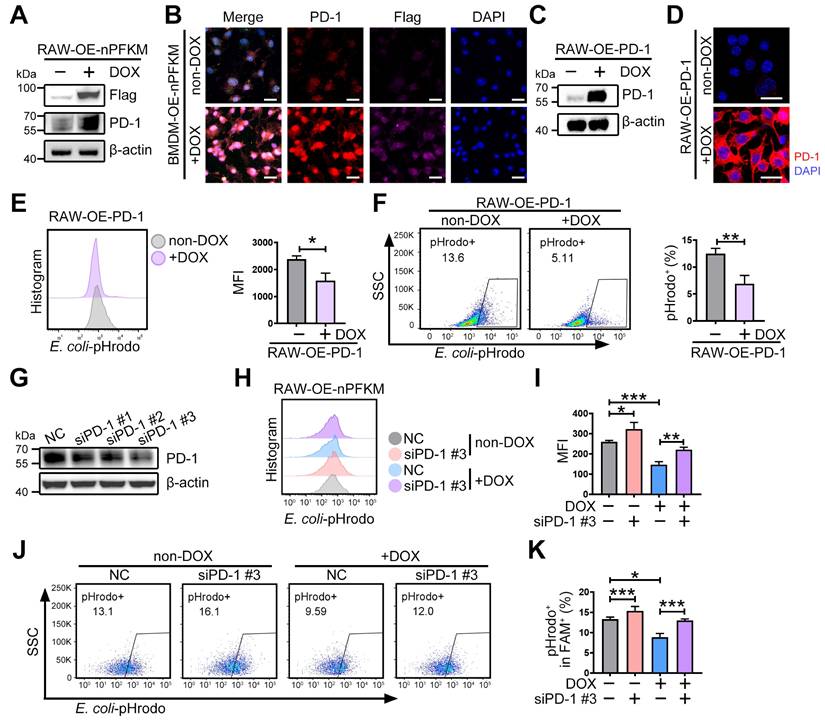

Nuclear PFKM boosts PD-1 expression and impairs macrophage phagocytosis. (A-B) After treating RAW-OE-nPFKM and BMDM-OE-nPFKM cells with or without DOX (600 ng/mL) for 48 h, the protein expression level of PD-1 was detected by (A) Western blotting analysis and (B) multiplex immunofluorescence. Scale bars, 20 µm. (C-D) RAW264.7-OE-PD-1 cells were treated with or without DOX (300 ng/mL) for 48 h, followed by validation via (C) Western blotting analysis and (D) immunofluorescence. Scale bars, 20 µm. (E-F) RAW264.7-OE-PD-1 cells were treated with or without DOX (300 ng/mL) for 48 h, and then co-cultured with E. coli-pHrodo for 1 h. The phagocytosis was assessed by flow cytometry. (G) RAW264.7 cells were transfected with PD1-targeting siRNA (siPD-1) or negative control siRNA for 24 h. The protein level of PD-1 was determined by Western blotting analysis. (H-K) After treating RAW-OE-nPFKM cells with or without DOX (600 ng/mL) for 48 h, the cells were transfected with PD-1 siRNA or a negative control siRNA for 24 h, followed by co-culture with E. coli-pHrodo for 1 h. The phagocytosis was assessed by flow cytometry. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired t-test for (E and F) and by one-way ANOVA for (I and K). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

Nuclear PFKM promotes PD-1 expression to inhibit macrophage phagocytosis

PD-1 provided negative feedback to macrophages that suppressed phagocytosis [30,31]. Therefore, to explore whether nuclear PFKM inhibits macrophage phagocytosis via up-regulating PD-1, we examined the PD-1 protein upon nuclear PFKM overexpression. Overexpression of nuclear PFKM resulted in an elevation of PD-1 protein expression in both RAW264.7 cells and BMDMs (Figure 6A-B, Figure S4A). Overexpression of PD-1 (Figure 6C-D) suppressed the phagocytosis of macrophages (Figure 6E-F), while PD-1 silencing rescued the phagocytosis inhibited by nuclear PFKM in macrophages (Figure 6G-K). These results confirm that PD-1 is the downstream effector of the PFKM-p53 axis in regulating macrophage phagocytosis.

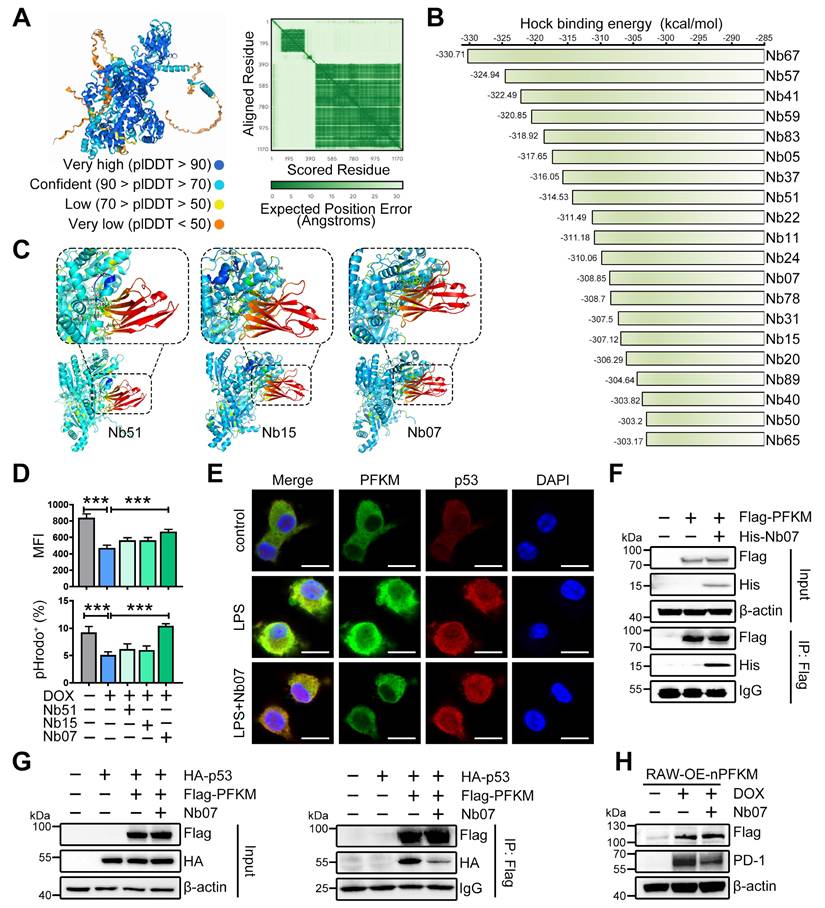

Nanobody Nb07 enhances macrophage phagocytosis by blocking the PFKM-p53 interaction

To develop the strategies for blocking the interaction of PFKM and p53, the PFKM-p53 protein interaction regions were predicted by AlphaFold3. High-confidence regions (pLDDT > 90) were selected (Figure 7A, Figure S5A), and virtual screening was then performed to identify single-domain antibodies (or nanobodies) with optimal structural compatibility. From the top 20 sequences with the highest predicted binding affinity to PFKM (Figure 7B), we selected Nb51, Nb15, and Nb07 for synthesis based on their capacity to occupy most of the PFKM-p53 binding surface (Figure 7C). Functional testing demonstrated that Nb51 or Nb15 only slightly improved macrophage phagocytosis, while Nb07 significantly restored the macrophage phagocytic capacity upon ectopic expression of nuclear PFKM (Figure 7D).

Nb07 only comprises a single heavy-chain variable domain with a molecular weight of approximately 14 kDa (Figure S5C), and a hydration particle size of 260.4 nm (Figure S5D). Nb07 presented low cytotoxicity (Figure S5E-F), and both in vivo and in vitro experiments validated that Nb07 was efficiently internalized by macrophages (Figure S5G-H).

To investigate whether Nb07 could impair the nuclear translocation of PFKM by disrupting PFKM-p53 binding, we treated BMDMs with LPS in the presence or absence of Nb07. Nb07 treatment decreased the LPS-induced nuclear accumulation of PFKM without affecting p53 nuclear localization (Figure 7E). Co-IP assay and SPR experiments verified that Nb07 can directly bind to PFKM (Figure 7F, Figure S5B, Table S5), thereby reducing PFKM interaction with p53 (Figure 7G), which subsequently abrogated nuclear PFKM-induced PD-1 up-regulation (Figure 7H). In addition, Nb07 treatment decreased LPS-induced PD-1 expression in BMDMs (Figure S6A). These data indicate that Nb07 could enhance macrophage phagocytosis by inhibiting the PFKM-p53-PD-1 axis, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic strategy against sepsis.

Nanobody Nb07 alleviates sepsis

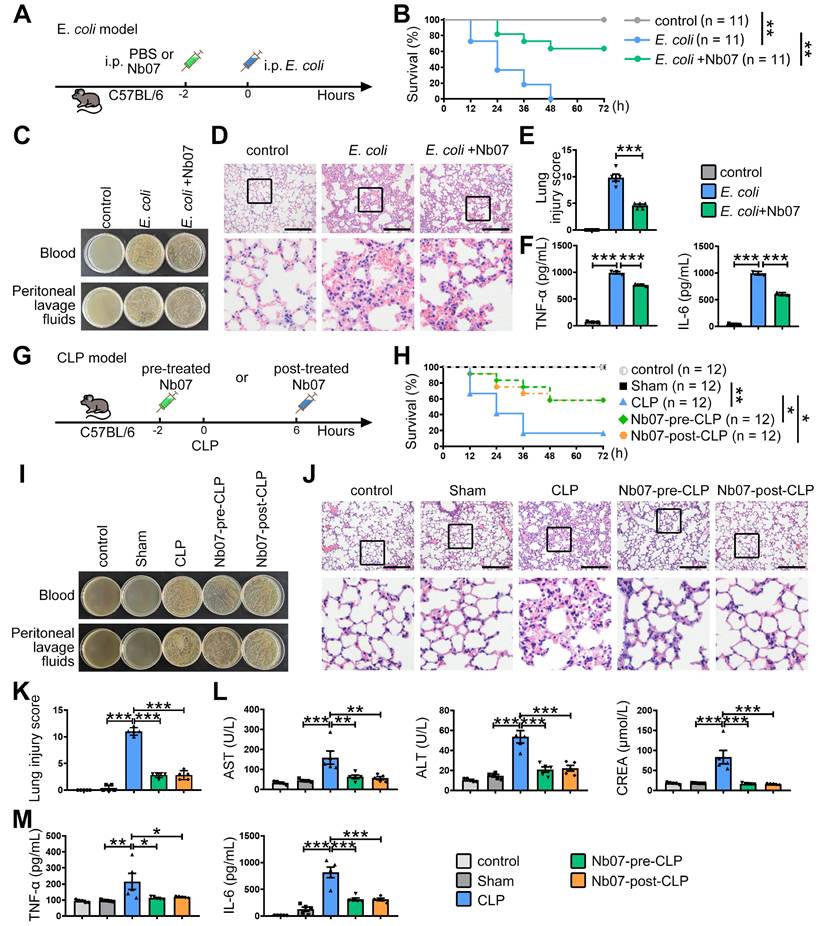

Finally, to evaluate the preventive effect of Nb07, mice were treated with Nb07 or PBS before intraperitoneal injection of E. coli to induce sepsis (Figure 8A). Nb07 treatment improved the survival rate of septic mice (Figure 8B), reduced bacterial loads in blood and peritoneal fluid (Figure 8C), and attenuated pathological features in lung tissues, including alveolar wall thickening, hyperemia, and inflammatory exudation (Figure 8D-E). Also, Nb07 treatment reduced the serum levels of TNF-α and IL-6 (Figure 8F). These data reveal that Nb07 can confer protection against E. coli-induced sepsis.

To further verify the therapeutic effect of Nb07, we used the well-established CLP-induced sepsis model. Mice received Nb07 either 2 h before (pre-treatment) or 6 h after (post-treatment) the CLP procedure (Figure 8G). Both pre-treatment and post-treatment improved the survival rate to 60% (Figure 8H). Compared with the CLP group, mice in both pre-treatment and post-treatment groups had less bacterial burden in the blood and peritoneum (Figure 8I). Nb07 treatment also alleviated the lung injury (Figure 8J-K) and reduced serum levels of the liver damage markers, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and kidney damage marker creatinine (CREA) (Figure 8L). Also, Nb07 treatment reduced the serum levels of TNF-α and IL-6 (Figure 8M). Additionally, Nb07 treatment also reduced the PD-1 expression in F4/80+ lung macrophages (Figure S6B). Taken together, our data indicate that Nb07 enhances bacterial clearance and mitigates sepsis in mice.

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate that infection-induced nuclear translocation of PFKM in macrophages impaired phagocytosis by enhancing p53-mediated PD-1 expression, thereby promoting sepsis progression. This impairment was reversed by Nb07, which blocked PFKM nuclear localization (Figure 7E) and mitigated sepsis development (Figure 8). Our findings highlight the therapeutic potential of targeting macrophage PFKM in sepsis.

PFKM deletion in myeloid cells mitigates sepsis development [15]. Although neutrophils and macrophages are the most abundant myeloid cell populations in early sepsis, RNA and protein analyses demonstrated that PFKM expression was higher in macrophages than in neutrophils (www.proteinatlas.org, Figure S7), suggesting that nuclear PFKM mainly affects macrophages during sepsis.

We confirmed that PFKM underwent nuclear translocation by binding to p53 (Figure 4). During sepsis, p53 indeed localized to the nucleus in F4/80+ macrophages (Figure S2, Movie S5-6). As a transcription factor, p53 is known to enter the nucleus under various stress conditions [32-34]. Notably, while stressors such as LPS, 5-FU, and ultraviolet irradiation all induced p53 nuclear accumulation and elevated PFKM protein levels, only LPS stimulation triggered the concurrent nuclear translocation of PFKM (Figure 7E, Figure S8). This indicates that PFKM-p53 nuclear translocation may be a sepsis-specific response.

The nuclear PFKM-p53 interaction promoted K120 acetylation of p53 (Figure 5D), a modification known to enhance its transcriptional activity and mediated by acetyltransferases CBP, p300, and Tip60 [29,35-37]. Nuclear PFKM overexpression slightly induced the mRNA levels of these acetyltransferases (Figure S3A). Moreover, inhibitors of CBP/p300 (C646) or Tip60 (MG149) suppressed the nuclear PFKM-induced p53 acetylation (Figure S3B), yet the precise mechanism by which PFKM promotes p53 acetylation requires further investigation.

Nb07 can block the PFKM-p53 interaction. (A) AlphaFold3 predicts the binding sites between PFKM and p53. (B) The top 20 affinity of nanobodies for blocking PFKM-p53 interaction. (C) Molecular docking of PFKM and separated nanobodies predicts the binding sites of Nb51, Nb15, and Nb07 with PFKM. (D) RAW-OE-nPFKM cells were treated with or without DOX (600 ng/mL) for 24 h, then co-treated with Nb51, Nb15, or Nb07 (300 ng/mL) for another 24 h, and then co-cultured with E. coli-pHrodo for 1 h. Phagocytosis was assessed by flow cytometry. (E) Representative immunofluorescent staining of BMDMs stimulated with or without LPS (100 ng/mL) for 96 h, with treatment with Nb07 (300 ng/mL) for another 24 h. Scale bars, 10 µm. (F) Co-IP and Western blotting analyze PFKM-Nb07 binding. (G) Co-IP and Western blotting analyze PFKM-p53 binding after Nb07 treatment (300 ng/mL) for 24 h. (H) RAW-OE-nPFKM cells were treated with or without DOX (600 ng/mL) for 24 h, then co-treated with Nb07 (300 ng/mL) for another 24 h. Western blotting analysis of PD-1 levels. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA for (D). *** P < 0.001.

The nanobody Nb07 has the potential to mitigate sepsis. (A) Schematic diagram of the experiment: Mice were injected with Nb07 (1 mg/kg) or PBS 2 h before intraperitoneal injection of E. coli (3 × 10⁷ CFU/mouse). (B) Survival curves of mice were recorded (n = 11). (C) Representative photos of plated blood and peritoneal lavage fluid from mice at 3 h after infection (n = 3). (D-E) Representative H & E staining of lungs at 24 h post-injection, and histological injury of the lungs was scored (n = 5). Scale bars, 200 µm. (F) Peripheral blood was obtained at 3 h, and the levels of TNF-α and IL-6 were measured by ELISA. (G) Schematic diagram of the experiment: Mice were intraperitoneally injected with Nb07 2 h before CLP operation or 6 h post-CLP operation. (H) Survival curves of mice were recorded every 12 h (n = 12). (I-M) Mice were sacrificed at 24 h (n = 5). (I) Representative photos of plated blood and peritoneal lavage fluid. (J) Representative H & E staining of lungs and (K) histological injury was scored. Scale bars, 200 µm. (L) The levels of AST, ALT, and CREA in serum were detected by an automatic biochemical analyzer. (M) The levels of TNF-α and IL-6 in serum were measured by ELISA. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA for (E-F) and (K-M) and by Mantel-Cox's log-rank test for (B) and (H). * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

We identified PD-1 as a key downstream target of the PFKM-p53 pathway. PD-1 expression is up-regulated in monocytes from septic patients [38] and macrophages from septic mice (Figure S4B, S6B, S9A), while PD-1 deletion protected mice from sepsis [39]. Mechanistically, PD-1 recruits and activates SHP-2 via its intracellular Y248-ITSM motif [40], leading to the dephosphorylation of key phagocytosis-initiating proteins, including Syk (Y352), PI3K-p85α (Y688/Y607), and PLCγ2 (Y753/Y759) [35,41]. Furthermore, SHP-2-mediated dephosphorylation of Vav impairs Rac activation and F-actin reorganization, which are essential for phagosome formation [42,43]. Nevertheless, these mechanisms are largely derived from studies on tumor cell clearance. How PD-1 regulates macrophage phagocytosis of bacteria during infection remains unclear.

Based on the PFKM-p53-PD-1 axis, we developed the nanobody Nb07 to target the PFKM-p53 interaction. We noted that while Nb07 significantly reduced PFKM-p53 binding, it only partially suppressed PD-1 up-regulation after overexpressing nuclear PFKM (Figure 7H), suggesting that additional pathways contribute to PD-1 expression. Researches show that the SMAD3-STAT3 complex and NF-κB response elements can bind to the Pdcd1 promoter directly and promote its transcription [44,45]. Furthermore, inflammatory and metabolic signals also upregulated PD-1 via the mTORC1 pathway [31]. These findings imply that PFKM-p53 represents a key, but not exclusive, driver of PD-1 in sepsis. Additionally, p53 can regulate diverse cellular processes, including cell cycle and apoptosis, via regulating a broad spectrum of genes beyond Pdcd1. It will be important to investigate whether Nb07 affects the expression of other classical p53 targets, such as CDKN1A (cell cycle), BAX, and PUMA (apoptosis), in future studies.

Unlike the monoclonal antibodies that target PD-1 directly and block its interactions with ligands such as PD-L1 or CD47 [46,47], Nb07 acts upstream to restore macrophage phagocytosis (Figure 7D). Although PD-1 knockdown enhanced the phagocytosis (Figure 6G-K), a PD-1 monoclonal antibody failed to rescue the impaired phagocytosis caused by nuclear PFKM overexpression (Figure S10), likely because bacteria lack PD-1 ligands, thereby explaining the limited efficacy of anti-PD-1 antibodies in sepsis clinical trials [48,49]. Notably, PFKM deletion reduced PD-1 but not PD-L1 expression in lung F4/80+ macrophages from septic mice (Figure S9), suggesting that nuclear PFKM regulates macrophage phagocytosis independently of PD-1-PD-L1 interaction. Additionally, compared with the monoclonal antibodies of PD-1 (molecular weight ~ 150 kDa), nanobodies have a smaller molecular weight and size (molecular weight ~ 14 kDa) (Figure S5C-D, Table S4), which may confer superior tissue penetration and lower cytotoxicity (Figure S5E-F). These properties could highlight the potential advantages of Nb07 in sepsis treatment.

Although Nb07 treatment affected the serum IL-6 and TNF-α levels in vivo unexpectedly (Figure 8), no such effect was observed in macrophages in vitro (Figure S11A-B). We speculated that Nb07 enhanced pathogen clearance through improved phagocytosis, thereby reducing the systemic inflammatory response triggered by persistent infection [50]. This is consistent with the observation [51] that impaired macrophage phagocytosis tended to be accompanied by elevated serum inflammatory cytokines in bacterial-infected mice (Figure 3E-F, Figure S12). It remains possible that the serum inflammatory cytokine levels could be produced by other immune cells in vivo.

During our present study, we used the Tet-On system to establish the stable cell lines, which are activated upon DOX treatment. To exclude the possibility that DOX might influence macrophage phagocytosis, we treated RAW264.7 cells with DOX for 48 h. Results showed that DOX treatment did not affect the phagocytosis of macrophages (Figure S13).

Our study has several limitations. First, while we identified the PFKM-p53 interaction, the post-translational modifications regulating PFKM nuclear translocation, such as phosphorylation and acetylation, remain unknown. Second, the therapeutic potential of Nb07 in humans is uncertain due to the relatively low homology between murine and human p53 (77.78%), despite high PFKM homology (97.82%). Third, the specific stage of sepsis during which PFKM undergoes nuclear translocation remains undefined, limiting insights into the optimal therapeutic window. Finally, although Nb07 may specifically inhibit genes co-regulated by the PFKM-p53 complex, the full repertoire of targets regulated by this complex remains to be elucidated.

Conclusion

In summary, we revealed that PFKM bound to and promoted p53 acetylation, enhancing p53-mediated transcriptional activation of Pdcd1, which subsequently suppressed macrophage phagocytosis and exacerbated sepsis. The nanobody Nb07 can restore macrophage phagocytosis by blocking PFKM-p53 interaction and ultimately alleviate sepsis, highlighting a novel therapeutic strategy for this condition.

Abbreviations

AAV: Adeno-Associated Virus; Ac: Acetylation; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; Arg1: Arginase 1; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; BMDMs: Bone marrow-derived macrophages; CDR3: Complementarity-Determining Region 3; CFU: Colony-Forming Unit; CLP: Cecal ligation and puncture; Co-IP/MS: Co-immunoprecipitation coupled with mass spectrometry; CREA: Creatinine; DMEM: Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium; DOX: Doxycycline; E: E. coli; ELISA: Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay; FBS: Fetal Bovine Serum; FITC: fluorescein isothiocyanate; H & E: Hematoxylin and Eosin staining; i.p.: Intra peritoneale; i.v.: Intra venosum; IVM: Ivermectin; KO: Pfkmf/f; Lyzcre+; LPS: Lipopolysaccharides; M-CSF: macrophage colony-stimulating factor; Nb: Nanobody; NLS: Nuclear Localization Signal; nPFKM: Nuclear PFKM; OE: overexpression; PAMPs: The pathogen-associated molecular patterns; PBMNCs: Peripheral blood mononuclear cells; PBS: Phosphate buffer solution; PCR: Polymerase chain reaction; PD-1: Programmed cell death protein 1; PD-L1: Programmed Death-Ligand 1; PFKL: Phosphofructokinase, Liver Type; PFKM: Muscle isoform of phosphofructokinase-1; PFKP: Phosphofructokinase, Platelet type; PFK1: Phosphofructokinase 1; PKM2: Pyruvate Kinase M2; p53: Tumor protein 53; P53-/-: p53 knockout mice; shp53: p53-targeting shRNA plasmid; siPD-1: PD1-targeting siRNA; sip53: p53-targeting siRNA; SPF: Specific pathogen-free; TAMs: Tumor-associated macrophages; TSS: transcription start site; UV: Ultraviolet radiatio; WT: Wild-type; 5-FU: 5-fluorouracil.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary movie legends, figures and tables.

Supplementary movie 1.

Supplementary movie 2.

Supplementary movie 3.

Supplementary movie 4.

Supplementary movie 5.

Supplementary movie 6.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Feng Guo for donating the pLVX-TetOne-Puro vector, Professor Hui Wang for donating Lyzcre+ mice, and Professor Jiehui Di (Xuzhou Medical University, Xuzhou, China) for offering p53 knockdown plasmids. We thank Dr. Fuxing Dong from the Public Experimental Research Center for his enthusiastic help in the experiment of laser scanning confocal microscopy.

Funding

This research was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (82502134 to Y.P., 82471910 to J.Y.), the Foundation for Universities of Jiangsu Province (25KJB310016 to Y.P., No. 23KJA310011 to J.Y.), the Open Competition Grant of Xuzhou Medical University (JBGS202202), the Scientific Starting Grants for Talented Early-career Researchers (D2022019 to Y.P.), the Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYCX25_3225 to B.J.), Jiangsu Training Program of Innovation and Entrepreneurship for Undergraduates (S202510313032 to R.X.). This work was supported by the Jiangsu Distinguished Professorship Program to J.Y.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to drafting the manuscript or critically revising its intellectual content, and all approved the final submitted version. B. Ji, Y. Pan, and J. Yang designed the study. B. Ji performed all major experiments with help from H. Guo, C. Yao, H. Zhu, R. Xing, M. Sun, Y. Cheng in experiments on mice, with help from X. Wang, R. Jiang, Z. Liu, S. Wang in experiments on cells, and with help from F. Xu and F. Zhang on bioinformatics analysis. X. Pan, B. Ji, J. Yang, and Y. Pan analyzed data and wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

Data supporting this research are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

J. Yang, B. Ji, and Y. Pan jointly applied for a patent on heavy-chain antibodies that block PFKM-p53 interactions and their applications. The other authors declare no competing interests.

References

1. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M. et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). Jama-J Am Med Assoc. 2016;315:801-10

2. Wright DJ, Trucco ME, Zhou J, Wolff C, Holbrook R, Margetta J. et al. Chronic kidney disease and transvenous cardiac implantable electronic device infection-is there an impact on healthcare utilization, costs, disease progression, and mortality? Europace. 2024;26:euae169

3. Ikuta KS, Swetschinski LR, Robles Aguilar G, Sharara F, Mestrovic T, Gray AP. et al. Global mortality associated with 33 bacterial pathogens in 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet. 2022;400:2221-48

4. Nakayama Y, Fujiu K, Yuki R, Oishi Y, Morioka MS, Isagawa T. et al. A long noncoding RNA regulates inflammation resolution by mouse macrophages through fatty acid oxidation activation. P Natl Acad Sci Usa. 2020;117:14365-75

5. Hiengrach P, Chindamporn A, Leelahavanichkul A. Kazachstania pintolopesii in Blood and Intestinal Wall of Macrophage-Depleted Mice with Cecal Ligation and Puncture, the Control of Fungi by Macrophages during Sepsis. J Fungi. 2023;9:1164

6. Akoumianaki T, Vaporidi K, Diamantaki E, Pène F, Beau R, Gresnigt MS. et al. Uncoupling of IL-6 signaling and LC3-associated phagocytosis drives immunoparalysis during sepsis. Cell Host Microbe. 2021;29:1277-93

7. Pan Y, Li J, Xia X, Wang J, Jiang Q, Yang J. et al. β-glucan-coupled superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles induce trained immunity to protect mice against sepsis. Theranostics. 2022;12:675-88

8. Pan Y, Li J, Wang J, Jiang Q, Yang J, Dou H. et al. Ferroptotic MSCs protect mice against sepsis via promoting macrophage efferocytosis. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13:825

9. Roquilly A, Jacqueline C, Davieau M, Mollé A, Sadek A, Fourgeux C. et al. Alveolar macrophages are epigenetically altered after inflammation, leading to long-term lung immunoparalysis. Nat Immunol. 2020;21:636-48

10. Zhao Q, Gong Z, Wang J, Fu L, Zhang J, Wang C. et al. A Zinc- and Calcium-Rich Lysosomal Nanoreactor Rescues Monocyte/Macrophage Dysfunction under Sepsis. Adv Sci. 2023;10:e2205097

11. Deng A, Fan R, Hai Y, Zhuang J, Zhang B, Lu X. et al. A STING agonist prodrug reprograms tumor-associated macrophage to boost colorectal cancer immunotherapy. Theranostics. 2025;15:277-99

12. Gauthier T, Yao C, Dowdy T, Jin W, Lim Y, Patiño LC. et al. TGF-β uncouples glycolysis and inflammation in macrophages and controls survival during sepsis. Sci Signal. 2023;16:eade385

13. Luo P, Zhang Q, Zhong T, Chen J, Zhang J, Tian Y. et al. Celastrol mitigates inflammation in sepsis by inhibiting the PKM2-dependent Warburg effect. Military Med Res. 2022;9:22

14. Tang Y, Jia Y, Fan L, Liu H, Zhou Y, Wang M. et al. MFN2 Prevents Neointimal Hyperplasia in Vein Grafts via Destabilizing PFK1. Circ Res. 2022;130:e26-43

15. Yao C, Zhu H, Ji B, Guo H, Liu Z, Yang N. et al. rTM reprograms macrophages via the HIF-1α/METTL3/PFKM axis to protect mice against sepsis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2024;81:456

16. Guo D, Meng Y, Zhao G, Wu Q, Lu Z. Moonlighting functions of glucose metabolic enzymes and metabolites in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2025;25:426-46

17. Fan F, Shen C, Tao L, Tian C, Liu Z, Zhu Z. et al. PKM2 regulates hepatocellular carcinoma cell epithelial-mesenchymal transition and migration upon EGFR activation. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:1961-70

18. Li Q, Ci H, Zhao P, Yang D, Zou Y, Chen P. et al. NONO interacts with nuclear PKM2 and directs histone H3 phosphorylation to promote triple-negative breast cancer metastasis. J Exp Clin Canc Res. 2025;44:90

19. Lim YC, Jensen KE, Aguilar-Morante D, Vardouli L, Vitting-Seerup K, Gimple RC. et al. Non-metabolic functions of phosphofructokinase-1 orchestrate tumor cellular invasion and genome maintenance under bevacizumab therapy. Neuro-Oncology. 2023;25:248-60

20. Xu P, Zhou W, Wang S, Wang L, Bai Y, Xing S. et al. Alisol A ameliorates vascular cognitive impairment via AMPK/NAMPT/SIRT1-mediated regulation of cholesterol and autophagy. Theranostics. 2025;15:9415-46

21. Yang S, Du P, Cui H, Zheng M, He W, Gao X. et al. Regulatory factor X1 induces macrophage M1 polarization by promoting DNA demethylation in autoimmune inflammation. Jci Insight. 2023;8:e165546

22. Li R, Li X, Zhao J, Meng F, Yao C, Bao E. et al. Mitochondrial STAT3 exacerbates LPS-induced sepsis by driving CPT1a-mediated fatty acid oxidation. Theranostics. 2022;12:976-98

23. Li R, Sun N, Chen X, Li X, Zhao J, Cheng W. et al. JAK2(V617F) Mutation Promoted IL-6 Production and Glycolysis via Mediating PKM1 Stabilization in Macrophages. Front Immunol. 2020;11:589048

24. Fernandes RA, Su L, Nishiga Y, Ren J, Bhuiyan AM, Cheng N. et al. Immune receptor inhibition through enforced phosphatase recruitment. Nature. 2020;586:779-84

25. Patera AC, Drewry AM, Chang K, Beiter ER, Osborne D, Hotchkiss RS. Frontline Science: Defects in immune function in patients with sepsis are associated with PD-1 or PD-L1 expression and can be restored by antibodies targeting PD-1 or PD-L1. J Leukocyte Biol. 2016;100:1239-54

26. Xu SB, Gao XK, Liang HD, Cong XX, Chen XQ, Zou WK. et al. KPNA3 regulates histone locus body formation by modulating condensation and nuclear import of NPAT. J Cell Biol. 2025;224:e202401036

27. Alvisi G, Manaresi E, Cross EM, Hoad M, Akbari N, Pavan S. et al. Importin α/β-dependent nuclear transport of human parvovirus B19 nonstructural protein 1 is essential for viral replication. Antivir Res. 2023;213:105588

28. Sanford JD, Jin A, Grois GA, Zhang Y. A role of cytoplasmic p53 in the regulation of metabolism shown by bat-mimicking p53 NLS mutant mice. Cell Rep. 2023;42:111920

29. Cao Z, Kon N, Liu Y, Xu W, Wen J, Yao H. et al. An unexpected role for p53 in regulating cancer cell-intrinsic PD-1 by acetylation. Sci Adv. 2021;7:eabf4148

30. Gordon SR, Maute RL, Dulken BW, Hutter G, George BM, McCracken MN. et al. PD-1 expression by tumour-associated macrophages inhibits phagocytosis and tumour immunity. Nature. 2017;545:495-9

31. Bader JE, Wolf MM, Lupica-Tondo GL, Madden MZ, Reinfeld BI, Arner EN. et al. Obesity induces PD-1 on macrophages to suppress anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2024;630:968-75

32. Daniely Y, Dimitrova DD, Borowiec JA. Stress-dependent nucleolin mobilization mediated by p53-nucleolin complex formation. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:6014-22

33. Fang J, Zou M, Yang M, Cui Y, Pu R, Yang Y. TAF15 inhibits p53 nucleus translocation and promotes HCC cell 5-FU resistance via post-transcriptional regulation of UBE2N. J Physiol Biochem. 2024;80:919-33

34. Ghosh M, Saha S, Bettke J, Nagar R, Parrales A, Iwakuma T. et al. Mutant p53 suppresses innate immune signaling to promote tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:494-508

35. Gong L, Shen Y, Wang S, Wang X, Ji H, Wu X. et al. Nuclear SPHK2/S1P induces oxidative stress and NLRP3 inflammasome activation via promoting p53 acetylation in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury. Cell Death Discov. 2023;9:12

36. Kabir M, Hu X, Martin TC, Pokushalov D, Kim YJ, Chen Y. et al. Harnessing the TAF1 Acetyltransferase for Targeted Acetylation of the Tumor Suppressor p53. Adv Sci. 2025;12:e2413377

37. Wei Z, Ye Y, Liu C, Wang Q, Zhang Y, Chen K. et al. MIER2/PGC1A elicits sunitinib resistance via lipid metabolism in renal cell carcinoma. J Adv Res. 2025;70:287-305

38. Fu Y, Wang D, Wang S, Zhang Q, Liu H, Yang S. et al. Blockade of macrophage-associated programmed death 1 inhibits the pyroptosis signalling pathway in sepsis. Inflamm Res. 2021;70:993-1004

39. Huang X, Venet F, Wang YL, Lepape A, Yuan Z, Chen Y. et al. PD-1 expression by macrophages plays a pathologic role in altering microbial clearance and the innate inflammatory response to sepsis. P Natl Acad Sci Usa. 2009;106:6303-8

40. Patsoukis N, Duke-Cohan JS, Chaudhri A, Aksoylar H, Wang Q, Council A. et al. Interaction of SHP-2 SH2 domains with PD-1 ITSM induces PD-1 dimerization and SHP-2 activation. Commun Biol. 2020;3:128

41. Li W, Mei W, Jiang H, Wang J, Li X, Quan L. et al. Blocking the PD-1 signal transduction by occupying the phosphorylated ITSM recognition site of SHP-2. Sci China Life Sci. 2025;68:189-203

42. Miller WD, Manion A, Mishra AK, Sheedy CJ, Bond A, Gardner BM. et al. CD47 inhibits phagocytosis through Vav dephosphorylation. J Cell Biol. 2025;224:e202502206

43. Li Y, Zhou H, Liu P, Lv D, Shi Y, Tang B. et al. SHP2 deneddylation mediates tumor immunosuppression in colon cancer via the CD47/SIRPα axis. J Clin Invest. 2023;133:e162870

44. Lei Z, Tang R, Wu Y, Mao C, Xue W, Shen J. et al. TGF-β1 induces PD-1 expression in macrophages through SMAD3/STAT3 cooperative signaling in chronic inflammation. Jci Insight. 2024;9:e165544

45. Tsuruta A, Shiiba Y, Matsunaga N, Fujimoto M, Yoshida Y, Koyanagi S. et al. Diurnal Expression of PD-1 on Tumor-Associated Macrophages Underlies the Dosing Time-Dependent Antitumor Effects of the PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitor BMS-1 in B16/BL6 Melanoma-Bearing Mice. Mol Cancer Res. 2022;20:972-82

46. Shen W, Shi P, Dong Q, Zhou X, Chen C, Sui X. et al. Discovery of a novel dual-targeting D-peptide to block CD24/Siglec-10 and PD-1/PD-L1 interaction and synergize with radiotherapy for cancer immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer. 2023;11:e007068

47. Hu L, Zhuang W, Chen M, Liao J, Wu D, Zhang Y. et al. EGFR Oncogenic Mutations in NSCLC Impair Macrophage Phagocytosis and Mediate Innate Immune Evasion Through Up-Regulation of CD47. J Thorac Oncol. 2024;19:1186-200

48. Gillis A, Ben Yaacov A, Agur Z. A New Method for Optimizing Sepsis Therapy by Nivolumab and Meropenem Combination: Importance of Early Intervention and CTL Reinvigoration Rate as a Response Marker. Front Immunol. 2021;12:616881

49. Hotchkiss RS, Colston E, Yende S, Crouser ED, Martin GS, Albertson T. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibition in sepsis: a Phase 1b randomized study to evaluate the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of nivolumab. Intens Care Med. 2019;45:1360-71

50. Gao Y, Liu K, Xiao W, Xie X, Liang Q, Tu Z. et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor confers protection against macrophage pyroptosis and intestinal inflammation through regulating polyamine biosynthesis. Theranostics. 2024;14:4218-39

51. Luo Z, Sheng Z, Hu L, Shi L, Tian Y, Zhao X. et al. Targeted macrophage phagocytosis by Irg1/itaconate axis improves the prognosis of intracerebral hemorrhagic stroke and peritonitis. Ebiomedicine. 2024;101:104993

Author contact

![]() Corresponding authors: Yuchen Pan: Xuzhou Medical University, No. 209 Tongshan Road, Yunlong District, Xuzhou City, Jiangsu Province, China, Postal Code: 221004. Tel: +86-181-21788403; Email: panyuchenedu.cn. Jing Yang: Xuzhou Medical University, No. 209 Tongshan Road, Yunlong District, Xuzhou City, Jiangsu Province, China, Postal Code: 221004. Tel: +86-136-45205760; Email: jingyangedu.cn. Xiucheng Pan: The Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University, No. 99 Huaihai West Road, Quanshan District, Xuzhou, Jiangsu Province, China, Postal Code: 221006. Tel: +86-051-685802297; Email: xzpxc68com.

Corresponding authors: Yuchen Pan: Xuzhou Medical University, No. 209 Tongshan Road, Yunlong District, Xuzhou City, Jiangsu Province, China, Postal Code: 221004. Tel: +86-181-21788403; Email: panyuchenedu.cn. Jing Yang: Xuzhou Medical University, No. 209 Tongshan Road, Yunlong District, Xuzhou City, Jiangsu Province, China, Postal Code: 221004. Tel: +86-136-45205760; Email: jingyangedu.cn. Xiucheng Pan: The Affiliated Hospital of Xuzhou Medical University, No. 99 Huaihai West Road, Quanshan District, Xuzhou, Jiangsu Province, China, Postal Code: 221006. Tel: +86-051-685802297; Email: xzpxc68com.

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact