13.3

Impact Factor

Theranostics 2026; 16(7):3507-3540. doi:10.7150/thno.126517 This issue Cite

Review

Recent advances in nanoparticles targeting TGF-β signaling for cancer treatment

1. Key Laboratory of the Ministry of Education for Advanced Catalysis Materials, College of Chemistry and Materials Science, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua 321004, China.

2. College of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310058, China.

3. Cancer Metastasis Alert and Prevention Center, College of Chemistry, and Fujian Provincial Key Laboratory of Cancer Metastasis Chemoprevention and Chemotherapy, Fuzhou University, Fuzhou 350108, China.

Received 2025-10-10; Accepted 2025-12-15; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

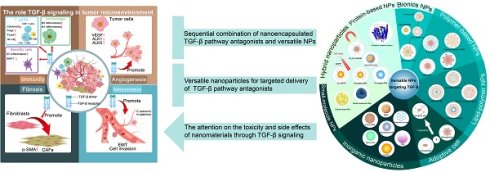

Multiple therapies blocking TGF-β signaling have been investigated in preclinical and clinical trials over the past few decades; nevertheless, the outcomes of clinical trials are disappointing due to the double-faced systemic effects of TGF-β and the complexity of the tumor microenvironment. Intelligent nanodelivery systems engineered with responsive stimuli and targeting capabilities address the Janus-faced biology of TGF-β through spatially precise inhibition. Nanoparticles targeting TGF-β reciprocally create a positive feedback loop that enhances the penetration and delivery efficiency of nanoparticles because of the role of TGF-β in remodeling the tumor microenvironment. This review first outlines the function of TGF-β signaling, summarizes various tools for suppressing TGF-β signaling and provides an exhaustive emphasis on advanced nanoparticles targeting TGF-β. This review elucidates the symbiotic interplay between TGF-β blockade and nanoparticles, where nanomaterial-based strategies refine the specificity of TGF-β targeting, while the blockade of TGF-β reciprocally enhances the efficiency of nanoparticle-mediated delivery. Additionally, current challenges and future directions are highlighted to guide the future development of TGF-β blockade strategies and nanoparticles for antitumor therapy.

Keywords: nanodrug delivery system, TGF-β blockade, cancer treatment, nanoparticle, nanocarrier

1. Introduction

Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) is a secreted cytokine that is involved in various biological activities, including tumor progression and metastasis, immunization inhibition and tissue reconstruction. TGF-β critically governs cellular proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and invasion across biological systems but presents a dualistic paradox in disease pathogenesis. During the initial phase of tumor development, it mediates tumor-suppressive effects through the induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis under normal physiological conditions [1]. However, in advanced malignancies, TGF-β is transformed into an oncogenic driver, promoting the excessive deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM), angiogenesis, immunosuppression and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [2]. Although multiple factors increase the complexity of TGF-β signal transduction, numerous clinical trials have proven the favorable antitumor effect of TGF-β blockade [3,4]. The most popular treatment strategy involves combining TGF-β pathway antagonists (such as antibodies, recombinant proteins, and small-molecule inhibitors) with other agents, including chemotherapeutic drugs [5], immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs, e.g., anti-PD-1/PD-L1) [6], and chimeric antigen receptor-modified (CAR)-T cells [7]. However, systemic exposure, off-target effect, and poor tissue penetration of TGF-β pathway antagonists themselves restrict the clinical translation of TGF-β blockade [8].

The advent of nanotechnology has revolutionized strategies for the precise modulation of TGF-β, a Janus-faced cytokine implicated in fibrosis, cancer, and autoimmune diseases. These next-generation nanoplatforms not only potentiate the therapeutic index through pathological site-restricted action but also maintain the physiological homeostasis of TGF-β in nonneoplastic tissues, thereby resolving the conundrum of therapeutic specificity versus systemic preservation of its biological functions.

In other words, the TGF-β signaling pathway offers an innovative direction for designing nanoparticles (NPs) for combination therapy and increasing NP delivery efficiency. The effective delivery of NPs to tumor sites remains a tremendous challenge due to the complex path through which they must traverse the tumor microenvironment (TME), which also affects the therapeutic effect of NPs [9]. TGF-β blockade could enhance delivery and penetration efficiency by weakening stromal barriers, improving vascular permeability and modulating immune responses. Pharmaceutical convergence between nanotechnology and TGF-β-targeted drug delivery systems (DDSs) has shown particular translational promise in multimodal therapeutic architectures that potentiate the effects of conventional chemotherapy, novel ICIs, and revolutionary immune cell therapy [10-12].

This review illuminates the symbiotic relationship evolving at the intersection of TGF-β biology and NPs, where nanotechnology-driven solutions increase the specificity of TGF-β targeting, whereas engineering of the TGF-β pathway reciprocally enhances the efficiency of nanotherapeutic delivery. Central to this discourse are NP systems capable of intrinsically neutralizing TGF-β via ligand scavenging or signaling cascade disruption, alongside advanced nanocarriers engineered for the spatiotemporally controlled delivery of TGF-β pathway antagonists such as monoclonal antibodies, gene-silencing RNAs, and TGF-β ligand traps. Concurrently, TGF-β inhibitors (TGF-βi) are being repurposed to potentiate nanodrug penetration by remodeling pathological microenvironments, such as by decompressing the fibrotic stroma or activating the immunosuppressive TME, thereby establishing a self-reinforcing therapeutic loop. Emerging frontiers further exploit multifunctional nanoplatforms that integrate TGF-β blockade with complementary modalities, including immunotherapies and conventional chemoradiation, capitalizing on the pleiotropic role of TGF-β in orchestrating multimodal antitumor responses. This bidirectional interplay represents a remarkable advancement intumor treatment, where nanotechnology and TGF-β targeting work together to specifically inhibit cancerous areas while protecting healthy tissues, effectively balancing their dual effects.

2. TGF-β signaling and function in tumor cells

TGF-β is a member of the secreted cytokine family, which is composed of three isoforms of TGF-β (TGF-β1, -β2, and -β3), activins, bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), and growth and differentiation factors (GDFs). In particular, TGF-β1 is the most comprehensively and actively researched family member. TGF-β receptors (TβRs) are high-affinity binding proteins located on the cell membrane and can be divided into three subtypes: TβR-I, TβR-II, and TβR-III. Almost all cells in the body can secrete TGF-β, whose receptor also exists on the cell surface [13].

The TGF-β signaling pathway plays an overarching role in diverse biological activities through the canonical suppressor of mothers against decapentaplegic (SMAD) -dependent pathway and non-SMAD pathways. TGF-β initiates key biological events primarily through the phosphorylation of SMAD2 and SMAD3. These transcription factors are pivotal SMAD family members and essential components of the TGF-β signaling cascade [14]. Activated SMAD2 and SMAD3 interact with SMAD4 to form a heterotrimer and enter the nucleus to modulate transcriptional activity. Non-SMAD signaling involves the collective pathways and downstream cascades triggered by TGF-β, including phosphorylation, acetylation, sumoylation, ubiquitination, and protein-protein interactions. For instance, TGF-β is known to initiate the non-SMAD signal-regulated kinases RAS, MEK1/2, and ERK1/2 to complete signal transduction.

TGF-β acts as a tumor suppressor in normal and premalignant cells but undergoes a functional switch to become a tumor promoter in advanced malignancies. In the initial phases of tumor development, the canonical TGF-β/SMAD 4 signaling pathway plays a tumor-suppressive role by inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [15]. SMAD4 plays a critical role at the G1/S checkpoint by inducing cell cycle arrest in the G1 phase through several cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors, including p15, p21, and p27 [16,17]. TGF-β induces intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis through the modulation of Bcl-2 family members, DAPK, caspases, FAS, and DNA damage-inducible (GADD) 45-β. TGF-β promotes apoptosis primarily through the SMAD-dependent pathway by upregulating proapoptotic genes (e.g., BIM, PUMA, and NOXA), but it can also induce apoptosis via non-SMAD pathways. These pathways include the activation of kinase signaling, such as JNK/p38 MAPK signaling, which in turn modulates the activity and expression of Bcl-2 family proteins [18]. Furthermore, TGF-β signaling initiates key executors such as DAPK, activate the caspase cascade, increase FAS-mediated signaling, and induce the expression of DNA damage-responsive genes (e.g., GADD45β).

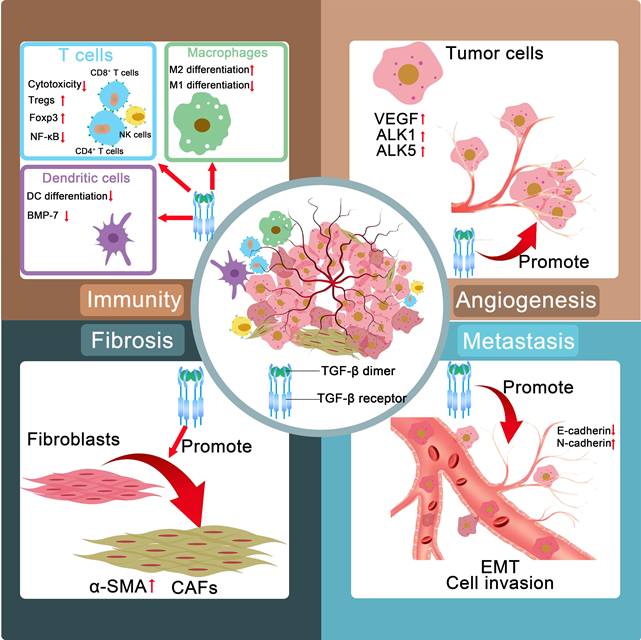

In advanced cancer stages, TGF-β facilitates ECM construction, angiogenesis, immunosuppression, EMT, and tumor aggression and metastasis (Figure 1). TGF-β orchestrates a protumorigenic microenvironment by driving ECM remodeling and fibrosis, leading to increased tissue stiffness and enhanced tumor invasion. TGF-β also promotes angiogenesis, ensuring a blood supply for the growing tumor. Crucially, it acts as a master regulator of immunosuppression by impairing the function of cytotoxic T cells and natural killer (NK) cells. Furthermore, TGF-β acts as a primary and crucial EMT inducer in late-stage tumors.

2.1 ECM construction

The TME consists of abnormal vasculature, a high density of tumor ECM and diverse cells (cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), immune cells, endothelial cells, and so forth). The ECM is a dynamic supramolecular network that consists of collagens, fibronectin, elastin, glycosaminoglycans and other proteins and affects the progression and prognosis of tumors. CAFs, as vital facilitators of tumor growth and progression, are identified by the expression of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), vimentin, and collagen I. The activation of the SMAD pathway, mediated via TβRII and TβRI, primarily drives the expression of proteins responsible for collagen deposition and matrix formation [19].

The role of TGF-β in late-stage tumors includes ECM construction, angiogenesis, immunosuppression, and the promotion of EMT. TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β; Tregs: regulatory T cells; Foxp3: forkhead box protein P3; NK cells: natural killer cells; BMP: bone morphogenetic protein; NF-κB: nuclear factor κB; DC: dendritic cell; CAFs: cancer-associated fibroblasts; α-SMA: α-smooth muscle actin; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; ALK: anaplastic lymphoma kinase; EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition; ECM: extracellular matrix.

TGF-β induces the differentiation of fibroblasts into activated fibroblasts with increased expression of α-SMA. This marker is widely regarded as the dominant feature associated with CAFs [20]. CAFs are derived from other resident stromal cells, such as epithelial or endothelial cells, through TGF-β-induced EMT. The differentiation of bone marrow-derived cells into CAFs is partially driven by TGF-β. And blockade of TGF-β can prevent mesenchymal stem cells from differentiating into CAFs [21].

2.2 Angiogenesis

The progression of solid tumors relies heavily on the establishment of functional tumor-associated blood vessels, which not only facilitate nutrient and oxygen delivery to proliferating neoplastic cells but also serve as conduits for metastatic dissemination. Notably, this intricate process of tumor vascularization requires coordinated ECM remodeling to provide structural support for the maturation of the nascent vasculature. Emerging evidence positions TGF-β as a pivotal orchestrator of this pathological process through multifaceted regulatory mechanisms.

TGF-β exerts dual regulatory effects on vascular homeostasis by differentially modulating the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK1 and ALK5) signaling pathways, thereby balancing endothelial cell proliferation and stabilization while simultaneously increasing ECM protein deposition to increase vascular integrity. Furthermore, this pleiotropic cytokine demonstrates an immediate proangiogenic capacity by rapidly inducing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) secretion, establishing a hypoxic TME that perpetuates angiogenic signaling cascades [22].

Beyond its immediate effects on endothelial activation, TGF-β coordinates comprehensive vascular maturation through a novel TGF-β-fibronectin signaling axis. This mechanotransduction pathway enhances pericyte-endothelial cell interactions, effectively stabilizing the immature vasculature while promoting the development of perfusion-competent blood vessels capable of sustaining tumor growth [23,24]. This multidimensional regulatory capacity positions TGF-β as a crucial regulator of tumor angiogenesis, simultaneously governing matrix remodeling, growth factor signaling, and vascular structural organization through distinct yet synergistic molecular mechanisms.

2.3 Immunosuppression

TGF-β induces immunosuppressive effects through multiple cell types. In natural killer (NK) cells, it attenuates cytotoxic activity via the dual inhibition of IFN-γ synthesis (through STAT5 pathway blockade) and effector molecule expression (via SMAD3-mediated transcriptional suppression of perforin/granzyme B) [25]. With respect to CD4+ T cells, TGF-β inhibits the differentiation of both Th1 and Th2 lymphocytes while simultaneously facilitating the generation and functional maturation of Th17 cells, Th9 cells, and regulatory T cells (Tregs). Notably, TGF-β is among the most powerful immunomodulatory cytokines involved in orchestrating Th1 cell differentiation and modulating its effector functions, demonstrating a dual regulatory capacity that positions it as a pivotal mediator of immune homeostasis [26]. TGF-β is capable of inducing the differentiation of CD8+ T lymphocytes into forkhead box protein P3 (Foxp3)-expressing Tregs [27]. TGF-β facilitates the phosphorylation of SMAD2 and Akt while concurrently inducing the formation of SMAD2/p-SMAD2 and Akt/p-Akt complexes, ultimately leading to the suppression of monocyte-derived dendritic cell (DC) differentiation. This molecular mechanism contributes significantly to tumorigenesis and malignant progression through the establishment of immunosuppressive microenvironments [28].

In addition, TGF-β drives the expansion and functional maturation of Tregs by transcriptionally activating Foxp3, thereby amplifying immune tolerance within the TME. Concurrently, TGF-β orchestrates macrophage polarization by suppressing nuclear factor κB (NF-κB)-mediated proinflammatory signaling, redirecting these myeloid cells toward a protumorigenic M2 phenotype characterized by arginase-1 overexpression and interleukin-10 secretion [29]. Notably, the synergistic interplay between Treg-derived immunosuppressive cytokines and M2-polarized tumor-associated macrophage (TAM)-secreted trophic factors establishes a self-reinforcing immunosuppressive mechanism, effectively paralyzing cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) activity while promoting tumor immune evasion. The dense ECM driven by TGF-β also restrains the deep penetration of immune cells besides the direct immunosuppressive effect of TGF-β [30].

2.4 Induction of EMT

During the EMT process, epithelial cells acquire mesenchymal characteristics, which enhances their migratory ability, invasiveness, and resistance to apoptosis [31]. In cell culture, epithelial cells stimulated with TGF-β exhibited a loss of E-cadherin expression and an elevated level of N-cadherin expression, along with morphological changes [32,33]. TGF-β is considered among the earliest EMT inducers and has been verified to serve as a crucial modulator of cancer cell progression and metastasis. The TGF-β signaling pathway is predominantly mediated by canonical pathways involving the transcription factors SMAD2, SMAD3, and SMAD4 and multiple noncanonical pathways. An elevated intratumoral concentration of TGF-β induces alterations in the EMT state of tumor cells, which also triggers significant reprogramming of the TME. The metabolism of carcinoma cells is profoundly affected by TGF-β, resulting in the establishment of a hypoxic environment within the TME [34]. Certain carcinoma cells may enter a dormant state, which could serve as a reservoir of therapy-resistant cells, laying the foundation for tumor recurrence [35-41]. Accumulating evidence has indicated that TGF-β induces epithelial tumor cells to acquire a mesenchymal phenotype characterized by increased invasiveness [42]. Thus, high expression of TGF-β1 has been verified to correlate with increased metastasis.

3. Blockade of TGF-β in cancer

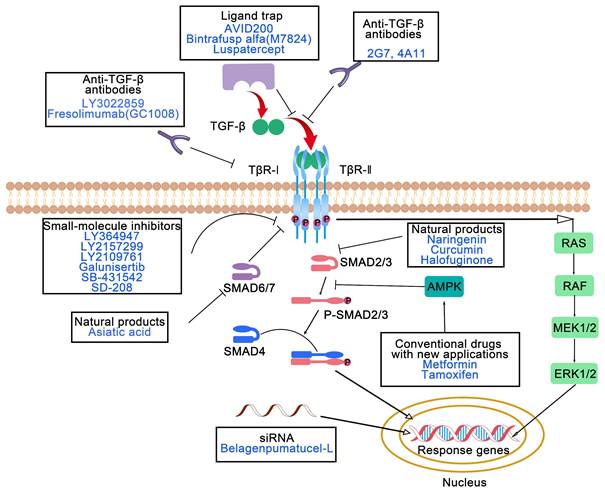

In terms of antitumor therapeutic targets, TGF-β pathway antagonists can be classified into seven types: antibodies that inhibit ligand/receptor interactions, small-molecule inhibitors, antisense oligonucleotides, ligand traps, vaccines, natural products and conventional drugs with new applications (Figure 2) [43]. Numerous these agents have been or are being assessed in clinical trials against diverse tumors. The diverse agents are discussed in more detail below.

3.1 Antibodies that inhibit ligand/receptor interactions

Direct blockade of TGF-β ligand-receptor interactions using antibodies has been shown to be a highly specific and promising intervention. By inhibiting signal transduction at its source, these antibodies regulate the activity of the TGF-β pathway, providing therapeutic approaches for related diseases [44-46]. 2G7 and 4A11 are two murine monoclonal antibodies that have been researched in drug-resistant animal models to restore sensitivity to cyclophosphamide (CTX) and cisplatin (CDDP) [47]. The human monoclonal anti-TGF-β antibody LY3022859 suppresses the activation of TβR-I- and TβR-II-mediated signaling by preventing the formation of ligand-receptor complexes. However, a safe and effective dose could not be determined in the phase I study of LY3022859 because the TGF-β receptor is ubiquitously expressed in the body [48].

Molecular mechanisms of action of TGF-β pathway antagonists. TGF-β pathway antagonists can be classified into seven types: antibodies that inhibit ligand/receptor interactions, small-molecule inhibitors, antisense oligonucleotides, ligand traps, vaccines, natural products and conventional drugs with new applications. TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β; TβR: TGF-β receptor; SMAD: suppressor of mothers against decapentaplegic; AMPK: adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase; RAS: rat sarcoma; RAF: rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma; MEK: mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; ERK: extracellular signal-regulated kinases.

Another human monoclonal antibody, fresolimumab (GC1008), was broadly evaluated in clinical trials of patients with metastatic breast carcinoma [49], renal cell carcinoma [50] and other malignancies [51] to assess the clinical response. Compared with a lower dose of GC1008, a higher dose of GC1008 during radiotherapy was achievable and well tolerated, with efficient immune activation and a prolonged median overall survival among patients with metastatic breast cancer [49]. Additionally, an analysis of functional T cells suggested that combining radiotherapy with GC1008 was ineffective at ameliorating T cell restriction by PD-1 [52], which encouraged the strategy of the combination of dual PD-1 and TGF-β suppression and radiotherapy. In addition, numerous challenges remain in optimizing the affinity, specificity, and therapeutic effect of antibodies [53].

3.2 Small-molecule inhibitors

Numerous small molecules can be classified into three categories according to their structures: pyrazole, imidazole and pteridine compounds. Most TβR-Ⅰ inhibitors are pyrazole derivatives, such as LY364947 (HTS-466284), LY2157299 (galunisertib), and LY2109761. LY2109761 suppresses the TGF-β-induced liver metastasis and progression of pancreatic carcinoma through dual targeting of TβR-I/II activity [54]. Galunisertib is being evaluated in clinical trials for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome, advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and metastatic pancreatic cancer. Data from phase II clinical trials (NCT01246986) have revealed that decreased TGF-β1 levels induced by galunisertib are related to longer overall survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma [55]. Galunisertib has advanced the most recent clinical trials among all small-molecule TGF-βi and has favorable pharmaceutical properties and selectivity. T LY2157299 was proven to facilitate the antitumor effect of nivolumab (anti-PD-1) in a phase II study (NCT02423343) [56].

TGF-βi based on imidazole and pteridine derivatives have been validated in preclinical studies but have not yet been tested in clinical trials. Both SB-431542 and its derivatives SB-505124 and SB-525334 possess an imidazole scaffold that suppresses the kinase activity of TβR-I, ALK4, ALK5 and ALK7. In preclinical models, SB-431542 has been demonstrated to have antitumor effects on breast carcinoma, colon cancer, osteosarcoma and malignant glioma [57-60]. It abates immune suppression by mitigating the population of Treg cells and rescuing the proliferation of T cells in a murine fibrosarcoma model [61]. The TβR-I kinase inhibitor SD-208 is the only molecule with a pteridine structure. According to a preclinical study in SMA-560 glioma-bearing syngeneic mice, SD-208 prolongs the survival by promoting immune responses [62]. While small-molecule TGF-βi demonstrate remarkable therapeutic potential for improving pharmaceutical properties and synergistic efficacy in combination with ICIs, their clinical treatment remains limited by structural limitations that compromise target specificity and unresolved challenges in pharmacokinetic optimization across diverse TME. Despite the promising preclinical outcomes in terms of metastasis suppression and immune modulation, the long-term therapeutic efficacy of these compounds is unclear because of emerging compensatory signaling pathways and insufficient structural diversity within existing scaffolds to address heterogeneous tumor resistance mechanisms.

3.3 Antisense oligonucleotides

RNA interference (RNAi) is an innovative approach for the specific knockdown of gene expression. Only a few clinical trials in which TGF-β was silenced by a siRNA (siTGF-β) have been conducted for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [63], advanced glioma [64, 65], and malignant melanoma [66]. In a phase II study of belagenpumatucel-L [63], a TGF-β2 antisense gene-modified tumor cell vaccine, a dose-dependent difference in survival was observed, and no significant adverse events were detected among NSCLC patients. RNAi has notable clinical advantages because it involves the use of sequence-specific gene silencing mechanisms to precisely modulate the expression of TGF-β [67]. Nevertheless, the clinical translation of RNAi therapeutics remains limited by intrinsic limitations, including the intrinsic instability of naked RNA molecules in the systemic circulation and inefficient tissue penetration of conventional delivery systems, which collectively contribute to reduced bioavailability and potential off-target effects [68]. Functionalized nanoscale delivery platforms can substantially increase the pharmacokinetic stability of RNAi payloads while enabling ligand-directed tumor targeting through surface engineering modifications, thereby addressing current delivery challenges with increased spatial control over therapeutic agent distribution.

3.4 Ligand traps

In addition to traditional ligands or receptor inhibitors, the design of “ligand traps” capable of efficiently capturing TGF-β ligands has gained attention as a novel strategy for precise therapy [69]. This strategy involves the engineering of receptor domains or fusion proteins that specifically bind to TGF-β ligands, thereby suppressing the downstream signaling pathways. Compared with traditional methods, ligand traps offer advantages such as high affinity, high specificity, and low toxicity, providing an original perspective and the potential to treat TGF-β-related diseases [70-73]. Several TGF-β ligand traps, such as AVID200, bintrafusp alfa (M7824), and luspatercept, can target TGFβ ligands through fusion proteins and prevent ligand-receptor binding. M7824 is a bifunctional fusion protein and is composed of a TGF-β “trap” fused to anti-PD-L1 antibody. Bintrafusp alfa has been investigated in numerous preclinical and clinical trials for treatment of various tumors [74-81]. Compared with monotherapy, dual suppression of PD-L1 and TGF-β by bintrafusp alfa results in effective antitumor effects in a preclinical animal model [80]. A clinical trial (NCT04247282) has indicated that one or two neoadjuvant doses of bintrafusp alfa were well tolerated without adverse reactions or surgical delays [81]. Dual PD-L1 and TGF-β inhibition efficiently enhanced T cell activation in a safe manner, increasing the feasibility of multimechanism neoadjuvant immunotherapy.

3.5 Vaccines

Vaccines targeting the TGF-β pathway, such as gemogenovatucel-T (Vigil, Vital) and belagenpumatucel-L (Lucanix), provide new emerging therapies with superior immunological effects in cancer treatment. Gemogenovatucel-T consists of a plasmid encoding the human immunostimulatory gene GMCSF and a bifunctional shRNA that specifically knocks down furin, TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 [82]. According to completed and ongoing clinical trials of gemogenovatucel-T or combination treatment with ICIs, the safety, efficient immune response, and antitumor effect of gemogenovatucel-T were confirmed in patients with different advanced gynecological cancers [83-88].

3.6 Natural products

Natural molecules derived from plants exhibit promising antitumor effects through the TGF-β signaling. Natural molecules suppressing TGF-β signaling include alkaloids, triterpenoids, diterpenoids, polyphenols, indoles, steroids, anthraquinone, and benzenoids. However, all these agents have been tested in vitro and in vivo but not in clinical trials. Triterpenoids, such as arjunolic acid [89], asiatic acid [90], betulinic acid [91], celastrol [92], and ginsenosides [93, 94], exhibit antitumor effects by suppressing TGF-β signaling. Lian et al. [90] reported that asiatic acid (a SMAD7 agonist) combined with naringenin (a SMAD3 inhibitor) synergistically regulated the TGF-β/SMAD signaling balance and inhibited the invasion and metastasis of melanoma and lung cancer. Diverse investigations have demonstrated that natural products effectively inhibit tumor invasion and metastasis by modulating the TME through the TGF-β signaling pathway. These studies provide experimental basis and potential clinical value of developing natural products that target TGF-β. For instance, curcumin not only suppressed EMT through TGF-β/SMAD2/3 signaling [95] but also reeducated CAFs by reducing α-SMA and COX-2 expression [96]. Halofuginone, a plant alkaloid derivative, inhibited osteosarcoma progression against lung metastases [97] and melanoma against bone metastasis [98] by inhibiting TGF-β/SMAD3 signaling. Salvianolic acid B, obtained from Salvia miltiorrhiza, suppressed TGF-β1-induced EMT and is a promising therapeutic agent for treating NSCLC [99].

3.7 Conventional drugs with new applications

Increasing evidence has verified that some conventional drugs, such as metformin, tamoxifen and pirfenidone, exhibit anti-tumor effect through the regulation of TGF-β signaling. Metformin, a medicine applied to treat type 2 diabetes, suppressed the TGF-β1-induced EMT through the activation of adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in various tumors, such as pancreatic carcinoma [100] and cervical carcinoma [101]. Another study also revealed that metformin decreased the expression of ECM components by modulating PSCs and reeducating TAMs [102]. Tamoxifen, an adjuvant chemotherapeutic, prolonged the survival of patients with almost all stages of estrogen receptor-positive breast carcinoma. Emerging evidence has indicated that the regulation of mitochondrial bioenergetics constitutes an innovative and efficacious approach to achieve the dual suppression of PD-L1 and TGF-β. Zhou et al. reported that tamoxifen efficiently suppressed PD-L1 and TGF-β expression by promoting AMPK phosphorylation [103]. Pirfenidone, an FDA-approved drug for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, inhibits tumor metastasis by preventing TGF-β/SMAD signaling in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) [104] and reducing collagen and E-cadherin levels through the TGF-β signaling pathway in colorectal carcinoma [105].

4. Strategies for the design of nanodelivery systems targeting TGF-β in cancer therapy

Both TGF-βi and their co-administration with ICIs have been proven to exert therapeutic benefits in clinical trials. However, the clinical translation of TGF-βi such as galunisertib, fresolimumab, and bintrafusp alfa is still hampered by significant limitations, including rapid systemic clearance, off-target toxicity, and insufficient drug penetration. These challenges often result in unsatisfactory efficacy and harmful side effects, hindering successful clinical trial outcomes. Nanodelivery strategies involving the encapsulation of these therapeutics can enhance the precise delivery of TGF-βi with reduced side effects on normal tissues, providing an effective platform to overcome the shortcomings of TGF-βi. On the one hand, TGF-β therapeutic agents have improved the penetration and therapeutic efficacy of antitumor drug-loaded NPs; on the other hand, the emergence of nanodelivery carriers has provided an effective approach to guarantee the biosafety and attenuate the systemic toxicity of TGF-β pathway antagonists for TME modulation and cancer treatment.

Furthermore, NPs with engineered physicochemical properties exploit the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect to achieve passive targeting and employ surface properties for active targeting, promoting specific accumulation and prolonged retention within the TME. This targeted aggregation significantly increases the local drug concentration where it is needed most, while simultaneously sparing normal organs. Moreover, researchers have increasingly shown that inorganic NPs may promote tumor metastasis through TGF-β signaling pathways, revealing the need for future investigations focusing on the potential adverse effects and safety concerns associated with NP applications. Consequently, these advanced strategies are pivotal for enhancing clinical trials for TGF-β blockade, enabling more informative and potentially successful evaluations of these promising agents in cancer treatment.

4.1 Sequential combination of nanoencapsulated TGF-β pathway antagonists and versatile NPs using a two-wave strategy

The convergence of nanotechnology and molecular targeting has catalyzed the development of multifunctional platforms capable of sequential microenvironmental normalization and tumor-specific payload delivery, exemplifying a new frontier in combinatorial therapeutic design. The following investigations adopted a sequential two-wave therapy: initial administration of nanoencapsulated TGF-β pathway antagonists to dismantle biological barriers within the TME through multifaceted mechanisms, followed by targeted delivery of drug-loaded NPs for cancer treatment. Sequential combination treatments involving TGF-β blockade and other therapeutic strategies, including chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and molecular targeted therapy, could allow for controlled spatiotemporal drug release and achieve efficient combination antitumor therapy (Table 1).

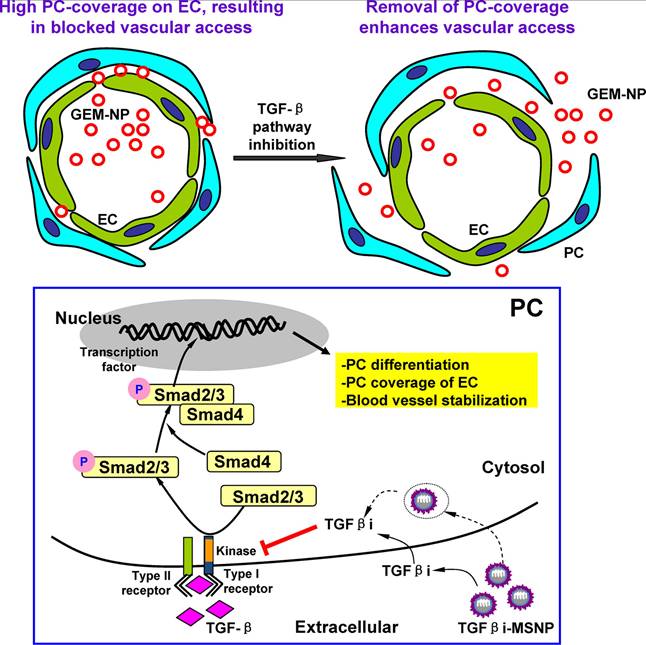

4.1.1 Nanodelivery of TGF-β pathway antagonists to increase the efficacy of chemotherapy

A challenging and central research objective is to improve the efficient delivery of nanomedicine, especially in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), in which the tumor comprises approximately 90% of the tumor stroma. The desmoplastic stroma of PDAC contains dense ECM and nontumor cells, especially pericytes. This stromal environment suppresses vascular fenestration and hinders the vascular access of NPs. Meng et al. demonstrated that polyethyleneimine (PEI)/polyethylene glycol (PEG)-coated mesoporous silica NPs (MSNPs) loaded with LY364947 efficiently reduced pericyte coverage of the vasculature by blocking TGF-β. Acting as a "first-wave" NPs, this treatment improved the accumulation of subsequent "second-wave" NPs (Figure 3) [106]. PEI-PEG-encapsulated MSNPs were favorable for the secure delivery of inhibitors due to their ability to maintain monodispersity in biological fluids, as well as their prolonged circulatory half-life benefitting from the PEG coating. According to the results of the in vivo imaging studies, compared with single-wave MSNPs, LY364947-bound MSNPs clearly improved the accumulation and vascular access of “Hard” (PEI-PEG-coated MSNP) or “Soft” (liposome) NPs subsequently injected into BxPC3 xenografts. This sequential combination therapy improved the delivery efficiency of gemcitabine while reducing the systemic toxicity of the chemotherapy.

Another study revealed that the sequential delivery of the natural products α-mangostin and triptolide by two nanoplatforms represents a unique strategy for the treatment of desmoplastic PDAC [107]. First, CAF-targeting CREKA peptide-modified PEG-PLA NPs (CRE-NP(α-M)) loaded with α-mangostin induced CAF deactivation, decreased collagen deposition, normalized the vascular system and improved blood perfusion by suppressing TGF-β/SMAD signaling [107]. Subsequent tumor cell-targeting CRPPR peptide-modified pH-triggered micelles loaded with hydrophobic triptolide (CRP-MC(Trip)) exerted excellent tumor-suppressive effects on a PANC-1/NIH3T3 subcutaneous tumor model with negligible damage to normal organs [107]. In addition to the most representative type of PDAC, chemotherapies for invasive breast cancer, melanoma and other desmoplastic tumors also face the problem of low penetration of chemotherapeutic drugs. The study and application of TGF-βi in other tumor models will offer novel strategies for the combined sequential treatment of desmoplastic tumors with superior therapeutic performance.

4.1.2 Nanodelivery of TGF-β pathway antagonists to enhance the efficacy of molecular targeted therapy

The dense and desmoplastic stroma of PDAC is primarily mediated by TGF-β. Beyond this stromal component, KRAS mutation has been recognized as a pivotal oncogenic driver, accounting for nearly 90% of PDAC cases. TGF-β receptors mediate the phosphorylation of components of the KRAS pathway, whereas KRAS signaling regulates the phosphorylation of SMAD. The dual targeting of TGF-β and KRAS mutations may break through biological barriers and signal transmission for efficient treatment of PDAC. Pei et al. constructed CGKRK-conjugated NPs (Frax-NPCGKRK) for delivery of the antifibrotic agent fraxinellone to suppress TGF-β signaling and developed siRNA-loaded lipid-coated calcium phosphate (LCP) biomimetic NPs (siKras-LCPApoE3) to silence mutant KRAS, which led to the development of a novel sequential targeting strategy [108]. NPs modified with TME-targeting peptide (CGKRK) could accurately deliver fraxinellone to CAFs in the TME, resulting in precise blockade of the TGF-β/SMAD pathway. Additionally, TGF-β blockade led to the inactivation of CAFs, a reduction in M2 macrophage polarization, and normalization of the vascular system in the TME, opening a new avenue for the subsequent delivery of siKras-LCP-ApoE3. This sequential strategy of TGF-β and silencing of mutant KRAS opens broader avenues for the treatment of PDAC.

4.1.3 Nanodelivery of TGF-β pathway antagonists to facilitate immunotherapy

Cancer immunotherapy still faces challenges, such as limited immune responses against antigens and an immunosuppressive TME. Increased levels of immunosuppressive TGF-β might be responsible for poor immune responses. By reprogramming the TME, the Leaf Huang group constructed LPH NPs that delivered siTGF-β to improve the efficacy of immunotherapeutic LCP NP vaccines for advanced melanoma [109]. A mixture of siTGF-β and hyaluronic acid condensed by protamine was coated with PEGylated liposomes through a stepwise self-assembly process to develop LPH NPs.

Sequential combination of nanoencapsulated TGF-β pathway antagonists and versatile NPs by a two-wave strategy.

| Sequential combination strategy | First-wave NPs loaded with TGF-β pathway antagonists | Second-wave NPs | Cancer cell type | Model | Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| To increase the efficacy of chemotherapy | PEI/PEG-coated mesoporous silica NP loaded with LY364947 | Liposome loaded with gemcitabine | BxPC3 | Female BALB/c nude mice | Two-wave approach improves the delivery efficacy of the gemcitabine by overcoming stromal barrier. | [106] |

| CREKA peptide modified PEG-PLA NPs loaded with α-mangostin | CRPPR peptide modified micelle loaded with triptolide | PANC-1 | BALB/c nude mice | Sequential delivery strategy can reduce ECM production by inactivating CAFs through TGF-β/SMAD signaling, increasing the efficacy of chemotherapy. | [107] | |

| PEGylated liposomes loaded with salvianolic acid B | Docetaxel-loaded PEG-modified liposomes | 4T1, NIH3T3 | Female BALB/c mice | Nanosystem encapsulating salvianolic acid B remodels the TME and enhances the efficacy of NPs loaded with docetaxel. | [112] | |

| Lipid NPs loaded with siTGF-β | Cabazitaxel-loaded albumin NPs | A549 | Female BALB/c nude mice | Combination of chemotherapy and TGF-β blockade perform superior effect against paclitaxel-resistant NSCLC. | [113] | |

| Albumin-bound triphenylphosphine tamoxifen conjugates | Albumin-bound paclitaxel | 4T1 | Female BALB/c mice | Nanosystem loaded with tamoxifen induces codepression of PD-L1 and TGF-β, boosting the chemo-immunotherapy of paclitaxel. | [103] | |

| To enhance the efficacy of molecular targeted therapy | Fraxinellone-loaded CGKRK peptide-modified PEG-PLA NPs | Lipid-coated calcium phosphate NPs for condensing KARS siRNA | PANC-1 | BALB/c nude mice | The pro-blockade of TGF-β leads to the inactivation of CAFs, the reduction of M2 macrophage polarization, and normalization of vascular system, opening the new avenue for the subsequent silencing KRAS mutation. | [108] |

| To facilitate the efficacy of immunotherapy | PEGylated liposome coated with protamine for codelivery of siTGF-β and HA | Mannose-modified lipid-calcium-phosphate loaded with Trp2 peptide and CpG oligonucleotides | B16/F10 | Female C57BL/6 mice | Targeted silencing of TGF-β in TME enhances the efficacy of the vaccine in malignant melanoma. | [109] |

| Fraxinellone | Fraxinellone-loaded AEAA-modified nanoemulsion | BPD6 | Female C57BL/6 mice | Fraxinellone nanoemulsion reverses the immunosuppressive TME and facilitates the therapeutic vaccination in desmoplastic melanoma. | [110] | |

| Combination of TGF-β pathway antagonists and vascular disrupting agent | LY2157299-loaded mPEG5k-b-PLA5k and maleimide- PEG5k-b-PLA5k | Poly(L-glutamic acid)-graft-poly(ethylene glycol)/combretastatin A4 conjugate | 4T1 | Female BALB/c mice | The cooperation of TGF-β inhibition and vascular disrupting agents significantly suppress the tumor growth and metastasis. | [111] |

TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β; NPs: nanoparticles; PEI: polyethyleneimine; PGA: polygalacturonic acid; PLA: polylactide; HA: hyaluronic acid; TME: tumor microenvironment; ECM: extracellular matrix; CAFs: cancer-associated fibroblasts; NSCLC: non-small cell lung cancer.

Schematic illustration of the two-wave strategy for TGF-β suppression and enhanced delivery efficiency of NPs. Adapted with permission from [106]. Copyright 2013, American Chemical Society.

LCP NPs were designed with a calcium phosphate core for the codelivery of a mixture of the Trp2 (SVYDFFVWL) peptide and phosphorylated serine residues together with CpG oligonucleotides (ODNs), whose surfaces were modified with mannose to achieve increased accumulation in the lymph nodes. Considering that TGF-β plays a dual role in different stages of tumors, the authors started the TGF-β siRNA treatment on day 13 to guarantee that the tumors were in a later stage. LPH NPs loaded with siRNA led to approximately 50% knockdown of TGF-β expression, resulting in increased infiltration of CD8+ T cells and decreased levels of Tregs. Compared with the single-vaccine treatment, the combination of LCP NPs and LPH NPs facilitated 52% inhibition of tumor growth. Targeted silencing of TGF-β in advanced tumors resulted in a robust immune response to the vaccine and represents an original combination strategy against immunosuppressive tumors. More importantly, paying attention to the manifestations of the TGF-β inhibition strategy in early tumors will increase therapeutic safety and promote its clinical application.

In another study by the Leaf Huang group, a nanoemulsion (NE) formulation was developed using plutonic F68 and the targeting ligand DSPE-PEG-AEAA on the surface to deliver fraxinellone, which modulates the TME and facilitates the immunotherapeutic efficiency of mannose-modified lipid calcium phosphate NPs containing modified BRAFV600E peptide (pSpSSFGLANEKSI)) and a CpG oligodeoxynucleotide adjuvant in desmoplastic melanoma [110]. In the absence of AEAA modification, compared with nontargeted NE, NE has a more preeminent tumor-targeting ability, indicating that fraxinellone inactivates CAFs. All these mechanistic insights collectively suggest that the spatiotemporal modulation of TGF-β signaling represents an innovative therapeutic approach for cancer management and is capable of simultaneously increasing treatment sensitivity and counteracting immune evasion.

4.1.4 Nanodelivery of TGF-β pathway antagonists combined with vascular disrupting agents

As a promising class of antitumor drugs, vascular disrupting agents (VDAs) directly and precisely destroy tumor blood vessels, inducing secondary tumor necrosis and suppressing cancer progression through the provision of nutrients and oxygen to cancer cells. However, bleeding tissue contains large amounts of TGF-β1, which increases the risk of tumor metastasis. The combination of VDAs and TGF-βi could achieve powerful tumor suppression. Xu et al. selected methoxy-poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly-(D,L-lactide) (mPEG5k-b-PLA5k) and maleimide-poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(D,L-lactide) (MalPEG5k-PLA5k) as carriers to encapsulate LY2157299 (LY) for the fabrication of A15-LY-NPs, whose surface was modified with coagulation-targeting peptide (A15) for accurate and efficient administration of TGF-βi to tumors [111]. Considering the biphasic function of TGF-β in tumor progression, they first examined the effects of LY on early-stage tumors. Bioluminescent signals from in vivo optical imaging revealed that LY-NPs suppressed the establishment of 4T1-luc tumor cell colonies in the lungs and liver, exerting a tumor-suppressive effect on early-stage tumors. By employing a targeted nanoplatform for the precise delivery of TGF-βi, this promising treatment modulates the TGF-β pathway with fewer off-target effects. When further combined with a nanomedicine-loaded VDAs (CA4-NPs), a threefold increase in the intratumoral accumulation of A15-LY-NPs and a 93.7% inhibition of growth were observed in 4T1 tumors. This work presents a targeted strategy for the precise delivery of TGF-βi and a combination strategy for TGF-βi and VDAs.

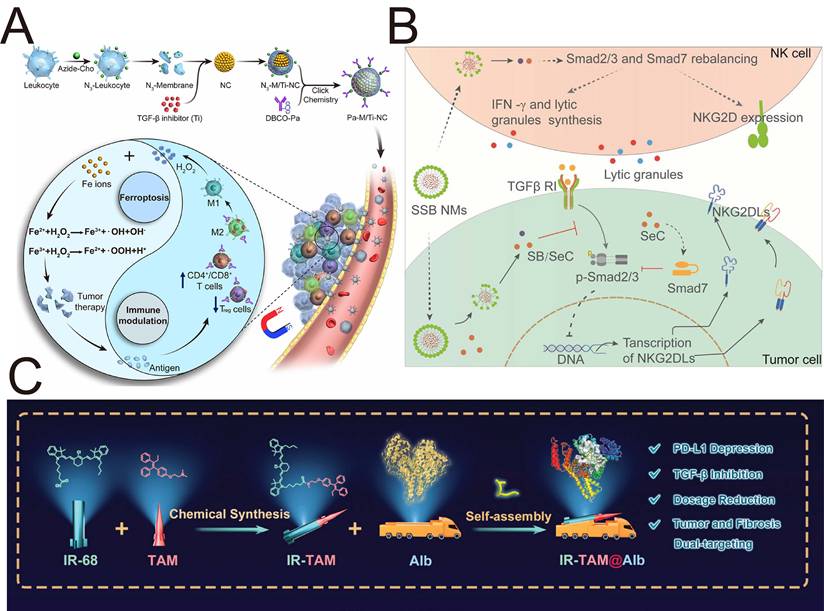

4.2 Recent advances in versatile NPs blocking TGF-β for cancer treatment

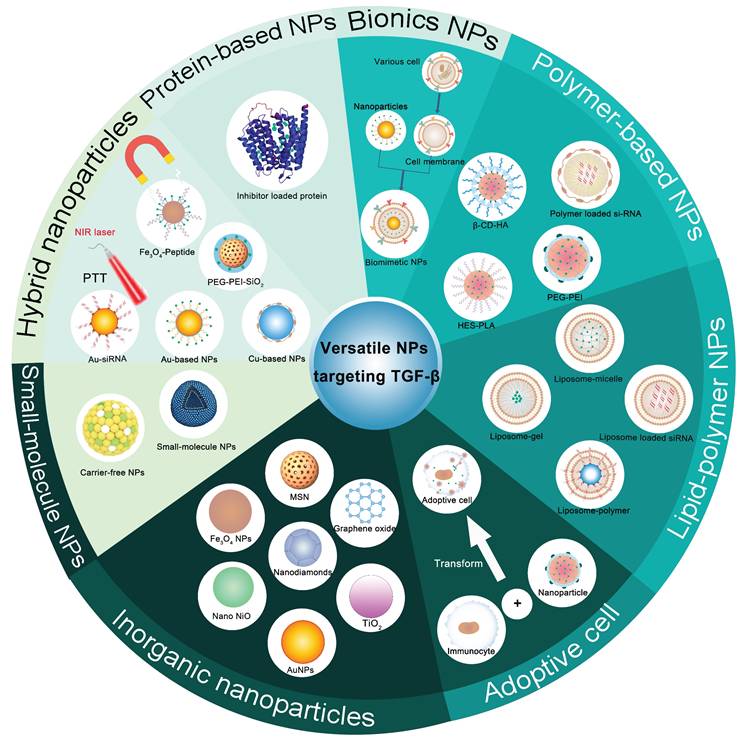

The majority of TGF-β therapeutic agents are associated with systemic toxicity and poor treatment outcomes. Targeted delivery of TGF-β therapeutic agents into the TME by versatile NPs (Figure 4) can not only achieve precise delivery of TGF-β pathway antagonists with enhanced therapeutic effects and safety but also open up a promising route for cancer treatment. Versatile NPs targeting TGF-β not only increase the spatial specificity and bioavailability of TGF-βi but also facilitate an improved intratumoral distribution of nanodrugs, thereby addressing key challenges in antitumor therapy, such as stromal barriers and heterogeneous drug delivery. The combination of stimulus-responsive release and stromal modulation represents a promising direction for the next generation of smart nanomedicines, potentially offering new avenues for improving therapeutic outcomes in solid tumors.

4.2.1 Polymer-based NPs

Polymeric NPs with high drug loading capacity and modifiability have emerged as promising carriers to increase the solubility, stability, and targeted delivery of therapeutics, ranging from hydrophobic small molecules and genetic drugs. In addition, responsive polymeric NPs can respond to specific stimuli, releasing their payload in a spatiotemporally controlled manner upon exposure to internal (e.g., pH, enzymes, and redox) or external (e.g., light, temperature, and magnetic fields) stimuli; their tunable properties make them ideal for designing versatile NPs for TGF-β blockade and tumor treatment (Table 2).

4.2.1.1 Enzymatic stimuli

Enzyme-responsive NPs can selectively react with specific enzymes expressed in tumor tissues, contributing to the precise release of therapeutics while minimizing side effects and improving therapeutic effects. Their adaptability makes them promising strategies for personalized and controlled therapy. For the codelivery of a hydrophobic TGF-βi and chemotherapeutic agents into the tumor site, hydroxyethyl starch-polylactide (HES-PLA) core-shell NPs (DOX/LY@HES-PLA) were established with dual α-amylase/pH-responsive properties to codeliver doxorubicin (DOX) and LY2157299 through ultrasonic emulsification and high-pressure homogenization [114]. The hydrophilic shell formed by HES could be disintegrated by endogenous α-amylase, eliminating the detrimental “PEG dilemma” of the hydrophilic layer as a hopeful replacement for PEG and triggering the release of DOX or LY2157299. Compared with the combination of free inhibitor and free DOX, this codelivery nanosystem suppressed tumor growth and inhibited pulmonary metastasis more effectively. The heterogeneous drug distribution of chemotherapeutic drugs is considered a crucial factor contributing to the insufficient efficacy of chemotherapy, which, in turn, promotes EMT and metastasis through the activation of the TGF-β signaling pathway. For instance, DOX, cisplatin, paclitaxel and camptothecin upregulate TGF-β1 expression in various tumor cells. The inhibition of TGF-β could suppress tumor progression and the inadequate efficacy of chemotherapy caused by inhomogeneous drug distribution.

Summary of polymer-based NPs targeting TGF-β for cancer treatment.

| Characteristic | TGF-β pathway antagonists | Nanoparticle/carriers | Tumor cell type | Model | Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic stimuli | LY2157299 | HES-PLA NPs for codelivery of DOX and LY2157299 | 4T1 | Female BALB/c mice | This codelivery nanosystem eliminates the insufficient chemotherapy promoted metastasis. | [114] |

| LY2109761 | Nanopolyplex self-assembled by DSPE-PEG-plectin-1 peptide and CPI-613 conjugated PEG for delivery of LY2109761 | PANC-1 | BALB/c nude mice | These nanopolyplexes achieve stromal normalization by inhibiting the crosstalk between cancer cells and pancreatic stellate cells, increasing the penetration and anti-tumor efficacy of nanopolyplex. | [118] | |

| SB-431542 | β-cyclodextrin-conjugated heparin and pH-responsive pseudorotaxane for codelivery of DOX and SB431542 | 4T1 | Female BALB/c mice | Dual α-amylase/pH responsive NPs modulate the TME and subsequently amplify the therapeutic effect of DOX. | [119] | |

| LY2157299 | Anti-PD-1 and LY2157299-loaded gelatinase-responsive mPEG-peptide -PCL NPs | H1299 | C57BL/6 mice | Gelatinase-responsive NPs overcome the immunotherapeutic resistance and achieve superior anti-tumor efficacy by cosuppressing PD-1 and TGF-β. | [132] | |

| ROS stimuli | LY2109761 | HCD and FC conjugate shells with BzPGA cores for codelivery of LY210976 and Ce6 | 4T1 | Female BALB/c mice | ROS-responsive core-shell NPs release the LY2109761 in a coordinated manner to achieve timely suppression upon PDT. | [120] |

| siTGF-β | 10-Hydroxycamptothecin grafted polymer core and PEG-PLL-DMMA shell loaded with siTGF-β | B16F10 | C57BL/6 female mice | The pH/ROS-responsive size-loss and charge-reversal nanoplatform improves chemoimmunotherapy by reprogramming the TME. | [122] | |

| pH stimuli | LY2157299 | PEG-PDPA copolymer self-assembled with Ce6 and LY2157299 | CT26 | Male BALB/c mice | The combination of nanoplatform-mediated SDT and TGF-β/SMAD blockade enhances the therapeutic efficacy of anti-PD-L1. | [123] |

| LY2157299 | Polymeric clustered NPs composed of PEG-PCL, PCL and PCL-CDM-PAMAM for codelivery of LY2157299 and siRNA silencing PD-L1 | Panc02 | C57BL/6 mice | Polymeric clustered NPs reverse the immunosuppressive microenvironment and activate the PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint for enhanced immunotherapy. | [124] | |

| Ingenol-3-mebutate | Single alcoholic hydroxyl (-CH(CH3)-OH polymeric vesicles loaded with ingenol-3-mebutate | Sarcoma-180 | Male C57BL/6 mice | These pH-sensitive polymeric vesicles overcome the hydrophobicity and pH instability of ingenol-3-mebutate, leading to the activation of anti-tumor immunity. | [125] | |

| LY2157299 | Nanomicelles composed of PgA-PAA conjugation for delivery of LY2157299 | HLF | - | These nanomicelles ensure the stability of LY2157299 in acidic pH of gastrointestinal tract. | [126] | |

| Hypoxic stimuli | LY2157299 | Amphiphilic polymer modified with enamine N-oxides and CBP peptide for delivery of LY2157299 and GEM prodrug | KPC, NIH3T3 | Male C57BL/6 mice | These charge-reversal NPs can initiate transcytosis across the ECM barrier to achieve deep penetration in PDAC. | [127] |

| Polymer based hydrogels and nanogels | LY3200882 | Thermosensitive hydrogel incorporating regorafenib and ROS-responsive nanogel loaded with LY3200882 | CT26 | Female C57BL/6 mice | This integrated hydrogel/nanogel system not only restrains the potential tumor metastatic threats induced by regorafenib, but also activates the immune responses by TGF-β blockade. | [128] |

| Gene medicine-loaded polymeric NPs | SB-505124 | β-cyclodextrin-PEI loaded with SB-505124 and the gene encoding murine IL-12 | B16, A549 | Female C57BL/6 mice | This codelivery system facilitates the sustained release of the SB-505124, ensuring efficient transduction of the adenoviral vector encoding the IL-12 gene. | [129] |

| siTGF-β | PLA-based nanovaccine for codelivery of α-Lactalbumin antigens, Toll like receptor ligands, and glutamate chitosan/siTGF-β | 4T1, EO771 | Female BALB/c mice, Female C57BL/6 mice | The synergistic combination of nanovaccine and OX40 suppresses tumor progression by eliciting antigen-specific immunity and silencing TGF-β. | [130] | |

| siTGF-β | Polypeptide loaded with TGF-β and Cox2 siRNA | Hepa1-6 | Female C57BL/6 mice | Gene silencing of TGF-β and Cox2 induces the activation of the immune TME by enhancing T cell penetration. | [133] | |

| Active targeted polymeric NPs | SD-208 | Anti-CD8a F(ab')2 fragments conjugated PEG-PLGA polymeric NPs | MC38, B16 | C57BL/6 mice | These T cell-targeting NPs restore the function of effector T cell and other suppressed immune cells and inhibit the tumor growth. | [131] |

HES: hydroxyethyl starch; PLA: polylactide; DOX: doxorubicin; HCD: hyaluronic acid-aldehyde-monosubstituted β-cyclodextrin; FC: hexadecanol-conjugated ferrocene; BzPGA: benzyl-modified poly(γ-glutamic acid); PgA: poly(glycolic acid); PEI: polyethyleneimine; PGA: polygalacturonic acid; PAA: polyacrylic acid; PEG-PLL-DMMA: polyanion poly(ethylene glycol)-blocked-poly(L-lysine)-modified dimethylmaleic anhydride; PDPA: Poly(2-(diisopropylamino)ethyl methacrylate); PCL: poly(ε-caprolactone); PCL-CDM-PAMAM: poly(amidoamine)-graftpolycaprolactone; GEM: gemcitabine; PEG-PAsp: poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(aspartic acid) block copolymer; SDT: sonodynamic therapy; ROS: reactive oxygen species.

Schematic illustration of multiple NPs targeting TGF-β. NPs: nanoparticles; NIR: near-infrared; PTT: photothermal therapy; PEG: polyethylene glycol; PEI: polyethyleneimine; AuNPs: gold NPs; TiO2: titanium dioxide NPs; Nano NiO: nickel oxide NPs; MSN: mesoporous silica nanoparticle; HES: hydroxyethyl starch; PLA: polylactide; β-CD-HA: hyaluronic acid-aldehyde-monosubstituted β-cyclodextrin.

The TME of PDAC is characterized by a dense and desmoplastic stroma that is largely regulated by TGF-β, which promotes cancer progression, therapeutic resistance, and poor prognosis [115,116]. Recent advances in nanotechnology and stroma-targeting strategies, particularly those designed to modulate TGF-β activity, have provided innovative approaches to overcome these challenges [117]. Based on the high expression of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) by stromal cells and the overexpression of plectin-1 on the surface of pancreatic cancer cells, Li et al. constructed a MMP-2-responsive PPC nanopolyplex to deliver hydrophobic CPI-613 (an antimitochondrial metabolism agent), which self-assembled with the amphiphilic DSPE-PEG-plectin-1 peptide to form a plectin-1-targeting p-PPCL nanopolyplex to deliver the hydrophobic protein LY2109761 [118]. The tumor-responsive nanopolyplex was cleaved by MMP-2 in TEM, triggering the decomposition of the nanoplatform and the release of LY2109761. This “flower-like” nanopolyplex achieved stromal normalization through TGF-β blockade, which increased the accumulation and penetration of the nanopolyplex and enhanced the antitumor effect of free CPI-613 [118]. In normal, healthy tissues, the TGF-β signaling pathway is subject to stringent regulation. TGF-β ligands are synthesized and secreted in an inactive form, remaining latent within the extracellular space. Subsequent activation of these ligands can be mediated by proteolytic cleavage by enzymes such as MMP2 and MMP9. High expression of MMP-2 in tumor tissue is always accompanied by active TGF-β ligands. MMP-2-responsive NPs provide a directional nanoplatform for the accurate delivery of TGF-β pathway antagonists.

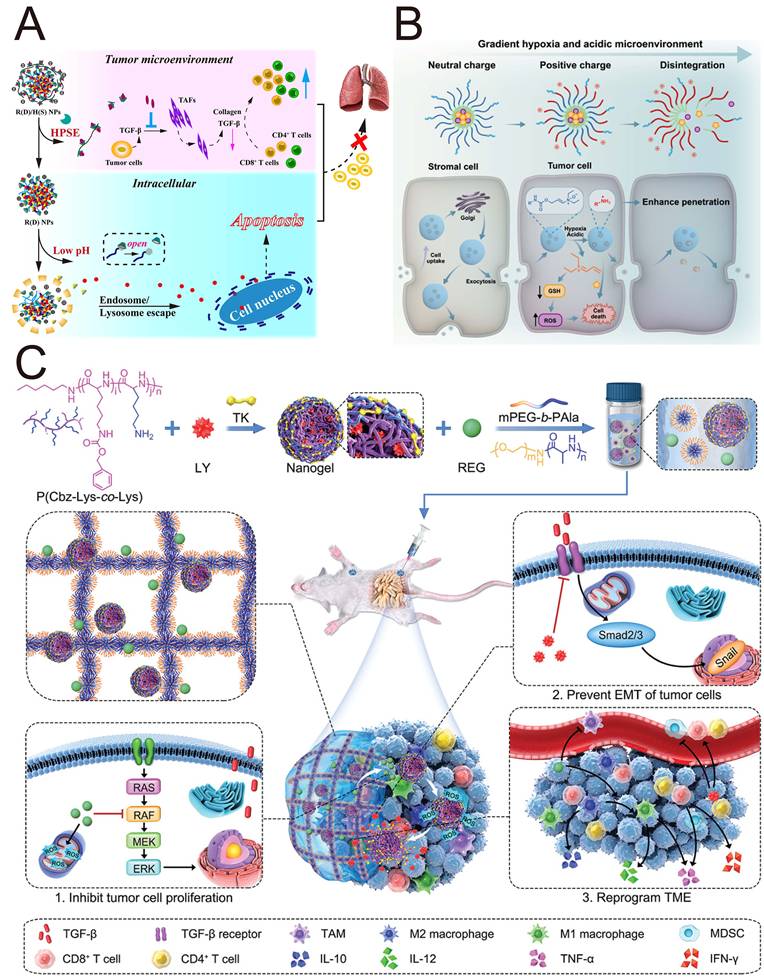

The use of grafted polymer nanocarriers to load chemotherapeutic drugs and TGF-βi may amplify the chemotherapeutic effect and suppress tumor metastasis. Zhang et al. [119] constructed hierarchically releasing heparanase/pH-responsive NPs (R(D)/H(S) NPs) based on β-cyclodextrin-conjugated heparin and a pH-responsive pseudorotaxane to encapsulate DOX and SB431542 (Figure 5A). The negative potential of biodegradable heparin prevented SB431542 from being cleared by immune cells, but it could be degraded by heparinase in the TME, triggering the release of SB431542. This study revealed that R(D)/H(S) NPs inactivated CAFs by SB431542, which reduced the expression of collagen I, thereby remodeling the TME and subsequently enhancing the anti-tumor effect of DOX. Enzyme-responsive nanocomplexes protected TGF-βi from being cleared by immune cells and facilitated their entry into cells through lysosomal escape to exert their functions.

4.2.1.2 Reactive oxygen species stimuli

Notably, reactive oxygen species (ROS), a crucial element of PDT, function as key mediators in the activation of latent TGF-β1 in the TME, ultimately causing its downstream detrimental signaling and sacrificing the therapeutic outcome of PDT. Han et al. revealed that PDT led to TGF-β1 accumulation-mediated immunosuppression through increased ROS/TGF-β1/MMP-9 and CD44-mediated local signaling [120]. To opportunely block TGF-β once PDT is performed, they designed core-shell NPs (LC@HCDFC NPs) for the delivery of LY2109761 and chlorin e6 (Ce6, photosensitizer) to complement PDT by blocking TGF-β through the remodeling of immunosuppression [121]. The amphiphilic shells were derived from a conjugate consisting of hyaluronic acid (HA)-aldehyde-monosubstituted β-cyclodextrin (HCD) and hexadecanol-conjugated ferrocene (FC), while the hydrophobic cores were composed of benzyl-modified poly(γ-glutamic acid) (BzPGA)-encapsulated LY210976 and Ce6. HCD conferred exceptional hydrophilicity but also increased CD44 receptor targeting efficiency via HA. Furthermore, the HCDFC inclusion complex facilitated the ROS-responsive release of LY210976, achieving timely inhibition of TGF-β once PDT was administered.

To cope with the immunosuppressive TME and address the low delivery efficiency of NPs, Dai et al. designed a pH/ROS-responsive size-loss and charge-reversal HCPT prodrug nanoplatform to condense siTGF-β for chemoimmunotherapy by reprogramming the immunosuppressive TME [122]. This study leverages a symbiotic interplay between TGF-β inhibition strategies and DDSs. A size-tuneable, ROS-responsive nanoplatform enables the efficient and precise delivery of TGF-βi. Concurrently, the inhibition of TGF-β promotes the deep penetration of nanotherapeutic agents by modulating the TME.

4.2.1.3 pH stimuli

Given the weakly acidic characteristics inherent to the TME, the rational design and engineering of pH-sensitive polymeric NPs emerges as a compelling strategic approach. In addition, electrostatic interactions drive the cellular uptake of positively charged NPs by negatively charged cancer cells. In a groundbreaking study, Huang et al. prepared a pH-responsive positively charged nanodrug via the self-assembly of poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(2-diisopropyl methacrylate) diblock copolymer (PEG-PDPA) using a nanoprecipitation method for the codelivery of the sonosensitizer Chlorin e6 (Ce6) and LY2157299 [123]. These positively charged NPs with much smaller particle sizes were conducive to efficient drug accumulation and endocytosis. This platform harnesses SDT to generate cytotoxic ROS bursts and induce robust immunogenic cell death (ICD), which simultaneously releases LY2157299 for the blockade of TGF-β/SMAD signaling and remodeling of the immune microenvironment. This strategy led to a 3.2-fold increase in anti-PD-L1 therapeutic efficacy against colorectal cancer liver metastases in preclinical models [123]. In this study, SDT-mediated ICD, reversion of the immunosuppressive TME by TGF-βi and immune checkpoint blockade constitute an immune cycle for the treatment of immunologically cold tumors.

Hydrophobic polymeric materials with positive charge can be loaded with two functionally distinct drugs via layer-by-layer self-assembly and subsequently delivered to distinct cellular targets within the tumor region. Wang et al. developed pH-sensitive polymeric clustered NPs self-assembled by poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(ε-caprolactone) (PEG-PCL), a PCL homopolymer and poly(amidoamine)-grafted polycaprolactone (PCL-CDM-PAMAM) to codeliver LY2157299 and a siRNA targeting the PD-L1 gene for enhanced immunotherapy [124]. Under conditions of acidic tumor extracellular pH, siPD-L1, which is attached to the surface of clustered NPs, is released with PAMAM as size-loss NPs to penetrate deep into the tumor tissue. LY2157299, which is loaded in the core of clustered NPs, exhibited sustained retention within the ECM to target pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs) because of the large size of the NPs. This nanoplatform enables the spatially and temporally controlled release of therapeutic agents, thereby synergistically cosuppressing the TGF-β pathway and the PD-L1 checkpoint for improved antitumor immunotherapy.

Studies of the polymer-based NPs targeting TGF-β for cancer treatment. (A) Schematic illustration of heparanase/pH-responsive NPs for TME modulation. Adapted with permission from [119]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. (B) Schematic illustration of hypoxia/pH-responsive charge-reversal NPs for deep penetration. Adapted with permission from [127]. Copyright 2025, American Chemical Society. (C) Schematic illustration of a hydrogel/nanogel composite for sequential release of drug and synergistic therapy. Adapted with permission from [128]. Copyright 2022, John Wiley and Sons.

The encapsulation of TGF-βi into NPs could overcome the pH instability and hydrophobicity of TGF-βi, thereby facilitating its clinical translation. Yu et al. reported a new TGF-βi, the natural product ingenol-3-mebutate (I3A), which reduced the proportion of Tregs and IL-6 expression and promoted the intratumoral infiltration of CTL [125]. After being encapsulated in polymeric vesicles with 'acidic nuclei' supplied by a single alcoholic hydroxyl (-CH(CH3)-OH), the obtained I3A-PM overcame the hydrophobicity and pH instability of I3A [125]. The development of multiresponsive DDSs will offer a more robust platform for the targeted delivery of these plant-derived hydrophobic drugs.

The development of NPs capable of pH-responsive release under alkaline conditions is equally essential for preventing the degradation of TGF-βi in the acidic gastrointestinal environment. Yu et al. developed an elastic nanocarrier to release LY2157299 in the alkaline pH of the colon through the conjugation of polygalacturonic acid (PgA) and polyacrylic acid (PAA) while resisting the acidic pH of the gastrointestinal tract [126]. These nanomicelles composed of PgA-PAA conjugates exhibited pH-responsive swelling behavior under alkaline conditions, thereby serving as effective stabilizers against the alkaline pH of the colon. Conversely, the aqueous solubility of PAA is limited at low pH, while its inherent mechanical elasticity provides structural support for the formation of nanomicelles, ensuring stability in the acidic pH of the gastrointestinal tract.

4.2.1.4 Hypoxic stimuli

The dense ECM mediated by the TGF-β/SMAD signaling pathway causes the collapse of the vascular system, indirectly leading to the formation of a hypoxic acidic and immunosuppressive TME in PDAC. The tunable physical properties of the NPs (e.g., particle size and surface charge) allow for deep penetration and efficient regulation of the TGF-β pathway, making them a powerful nanosystem for TGF-βi delivery. Hypoxia/pH-responsive charge-reversal NPs (GemC18/Gal@CPLNO) with transcytosis functions were constructed by Zhang et al. to adapt to the pathological characteristics of PDAC (Figure 5B) [127]. An amphiphilic polymer with hypoxia-responsive enamine N-oxides and the collagen-binding peptide CBP was synthesized to incorporate LY2157299 and a stearic acid-modified gemcitabine prodrug (GemC18) by self-assembly for stromal reprogramming and immune activation. Enamine N-oxides first achieved hypoxia-responsive transcytosis through self-sacrificial reduction to produce positively charged NPs. Simultaneously, the lysine residues of the polymer triggered cascade transcytosis by turning the neutral charge to a positive charge in response to the acidic TME. These positively charged NPs can initiate transcytosis across the ECM barrier to achieve deep penetration, releasing TGF-βi and other drugs in response to hypoxic and acidic microenvironments.

4.2.1.5 Polymer-based hydrogels and nanogels

Hydrogels and nanogels represent two classes of biomaterials that are extensively utilized for controlled drug delivery. By incorporating nanogels into the three-dimensional network of hydrogels, the hydrogel/nanogel system achieves not only localized drug delivery through hydrogels whose mechanical properties match those of biological tissues but also cascade drug release by nanogels whose core can encapsulate another therapeutic agent. Li et al. constructed a thermosensitive hydrogel (Gel/(REG+NG/LY)) incorporating regorafenib and a ROS-responsive nanogel loaded with LY3200882 for spatiotemporally and sequentially controlled release in colorectal tumors (Figure 5C) [128]. Owing to the prestumoral injection, this injectable hydrogel has fewer systemic side effects. The earlier thermosensitive release of REG increased the production of intracellular ROS after injection, splitting the thioketal linker within the nanogel and leading to the subsequent release of LY3200882. This sequential drug delivery nanosystem not only restrained the potential tumor metastatic threats induced by REG but also increased immune responses to the immunosuppressive TME through TGF-β blockade. This integrated hydrogel/nanogel system enables sequential and cascade drug release, thereby improving the spatiotemporal control of drug delivery and potentially increasing treatment efficacy in complex disease environments such as tumors.

4.2.1.6 Gene medicine-loaded polymeric NPs

Polymeric carriers offer a great opportunity to package hydrophobic TGF-β and negatively charged gene medicines into one system for effective treatment. As TGF-β and IL-12 play diametrically opposing roles within the TME, coupling IL-12 delivery with TGF-β blockade could increase local immune responses to tumors, constituting a particularly potent treatment modality. Jiang et al. designed a versatile polymeric carrier, β-cyclodextrin-PEI, to encapsulate SB-505124 and the gene encoding murine IL-12 for immunotherapy of metastatic malignant melanoma [129]. This nanosystem facilitated the sustained release of SB-505124 while ensuring efficient transduction of the adenoviral vector encoding the IL-12 gene. By incorporating responsive bonds into nanomaterials, responsive sequential release can be achieved for more precise combination treatments.

Multilayered polymeric NPs serve as excellent nanosystems to protect siRNAs targeting TGF-β1 (siTGF-β1) from inchoate decomposition and achieve the sustained release of gene drugs in vivo. Peres et al. constructed a poly(lactic acid) (PLA)-based nanovaccine for the codelivery of α-lactalbumin antigens, Toll-like receptor ligands, and glutamate chitosan/siTGF-β [130]. This nanovaccine combined with the agonist immune checkpoint OX40 synergistically inhibited tumor progression and prolonged overall survival due to antigen-specific adaptive immunity and TGF-β silencing derived from the nanovaccine. This study further confirms that TGF-βi also improve the effectiveness of antigen-presenting cell checkpoint inhibitors, thereby broadening the scope of application of TGF-βi and providing valuable insights for clinical trials involving both ICIs and TGF-βi.

4.2.1.7 Actively targeted polymeric NPs

Polymeric NPs engineered for active targeting can faithfully replicate the protracted growth dynamics of human tumors. T cell targeting NPs that accurately deliver immunomodulatory TGF-βi to tumor sites can improve T cell activity better than free TGF-βi and passive NPs can, with minor side effects. CD8+ T cells targeted polymeric NPs promote the accumulation of the immunomodulatory agent SD-208, restoring the activity of CTL and inhibiting tumor growth. Notably, the treatment achieves these effects at one logarithm lower dosage of anti-PD-1 and anti-SD-208, whereas free small-molecule drugs have no effects at the same dosage [131]. Polymer-based NPs represent among the commonly employed drug delivery systems; however, strategies utilizing actively targeted polymeric systems for the delivery of TGF-βi remain relatively scarce. Further study is warranted to elucidate the relationship between TGF-β and TME-specific overexpression of receptors for the development of actively targeted DDSs.

4.2.2 Inorganic NPs

Over the past few decades, inorganic NPs have presented a remarkable opportunity as drug delivery carriers because of their facile modification, stimuli-responsive drug release mechanisms, and imaging capability. Notably, inorganic NPs can intrinsically modulate the TGF-β signaling pathway, resulting in an antitumor effect through the blockade of TGF-β signaling in cancer or adverse effects on health through the activation of TGF-β (Table 3) [134]. A focus on the biosafety of inorganic NPs and their side effects on normal tissues is crucial for promoting their clinical application.

Summary of inorganic NPs targeting TGF-β.

| Characteristic | Nanoparticle/carriers | Cancer cell type | Model | Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic NPs suppress the TGF-β signaling pathway | AuNPs | MBT-2 | Female (either C3H/HeN or NOD-SCID) mice | AuNPs attenuate the EMT through the formation of AuNP-TGF-β1 conjugates. | [136] |

| AuNPs | A2780-CP20, CAFs | - | AuNPs with size in 20 nm inactivate the CAFs by blockade of TGF-β1, PDGF, and other markers of CAFs. | [137] | |

| Carbon nanodiamonds | A549 | Nude mice | Nanodiamonds suppress the TGF-β by inducing the lysosomal decomposition of TGF-β receptors. | [138] | |

| Metallofullerenol-based Gd@C82(OH)22 NPs | MDA-MB-231 | Female BALB/c nude mice | Gd@C82(OH)22 NPs eliminate the CSCs and impede the EMT via suppression of HIF-1α and TGF-β. | [139] | |

| TiO2 NPs | A549 | Zebrafish, C57BL/6 mice | TiO2 NPs suppress the EMT progression by binding to the TβRI/II. | [140] | |

| Inorganic NPs activate the TGF-β signaling pathway | Nano-TiO2 | SW480 | - | Nano-TiO2 exhibits the toxic and side effect by activation of the TGF-β/MAPK and Wnt pathways. | [142] |

| Nano NiO | HepG2 | Male wistar rats | Nano NiO promotes the EMT progression and ECM deposition through TGF-β signaling pathway, resulting in hepatic fibrosis. | [143] | |

| TiO2 nanofibers | A549 | BALB/c nude mice | TiO2 nanofibers cause lung epithelial cells to obtain an aggressive tumor phenotype. | [144] | |

| PEI coated MNPs | HeLa | - | PEI-MNPs lead to tumor progression through the induction of autophagy and the activation of the NF-κB and TGF-β. | [145] | |

| Graphene oxide | 4T1 | Female BALB/c mice | GO activates the TGF-β signaling to exert prometastatic effects in a dose-dependent manner. | [146] | |

| AgNPs | - | Male and female ICR mice | Small-sized AgNPs are more active at triggering toxicological or biological responses than large-sized AgNPs. | [147] | |

| AlO NPs | KLN 205, HeLa, A549, SKOV3 | Female DBA/2 mice | Wire shaped AlO, but not spherical shaped AlO NPs, leads to tumor-associated inflammation and metastasis. | [148] |

AuNPs: gold NPs; TiO2: titanium dioxide NPs; NiO NPs: nickel oxide NPs; PEI: polyethyleneimine; MNPs: magnetic NPs; GO: graphene oxide; AlO NPs: aluminum oxide NPs; AgNPs: silver NPs; TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β; CAFs: cancer-associated fibroblasts; EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition; ECM: extracellular matrix.

4.2.2.1 Inorganic NPs suppress the TGF-β signaling pathway

By serving as nanocarriers or therapeutic agents, gold NPs (AuNPs) are broadly applied because of their unique physical properties [135]. AuNPs attenuate the EMT through the formation of AuNP-TGF-β1 conjugates, which result in the inactivation of the TGF-β1 [136]. Additionally, in vivo experiments indicated that AuNPs increased tumor immunity by increasing the infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and interfering with TGF-β signaling in MBT-2 tumors [136]. Zhang et al. demonstrated that AuNPs with a size of 20 nm inactivated CAFs by regulating the expression of fibroblast activation- or inactivation-associated markers, such as the blockade of TGF-β1, PDGF, and other markers [137]. This study helps us determine the role of AuNPs in interfering with multicellular communication within the TME.

Carbon nanodiamonds, a unique class of carbon NPs, bind to TβR-II, promote its lysosomal degradation and inhibit the transduction of TGF-β signaling [138]. Nanodiamonds suppress tumor invasiveness and induce macrophage polarization toward the antitumor M1 phenotype, indicating potential therapeutic effects on cancer. Metallofullerenol-based Gd@C82(OH)22 NPs, which are virus-like morphological nanocages, exert inherent antitumor effects on triple-negative breast cancer cells, with negligible side effects on normal mammary epithelial cells [139]. Under normoxic and hypoxic conditions, the Gd@C82(OH)22 NPs eliminate CSCs and impede EMT by suppressing the expression of HIF-1α and TGF-β, further emphasizing their therapeutic potential.

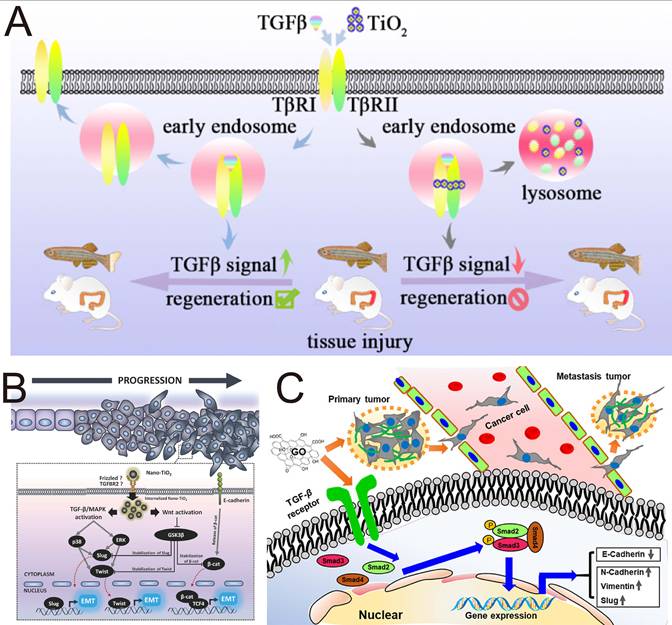

Titanium dioxide NPs (TiO2 NPs) are among the most extensively produced nanomaterials and are widely applied in food production, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals. Studies have shown that TiO2 NPs are capable of inhibit EMT with negligible cytotoxicity toward human lung epithelial A549 cells (Figure 6A). In terms of mechanism, TiO2 NPs bind to the TGF-β receptors TβRI/II, promote the trapping of TGF-β receptors in the lysosome, and interfere with the phosphorylation of SMAD2/3 [140]. Zinc oxide (ZnO) NPs are unique metal oxide nanomaterials that have garnered significant attention in the biomedical field due to their ability to produce zinc ions (Zn2+) and ROS. Metal ions and ROS act as critical modulators of stem cell physiology and significantly influence their metabolic processes and immunological functions. Recent research indicates that ZnO NPs can efficiently inhibit the production of TGF-β and α-SMA in adipose-derived stem cells, exhibiting significant potential for treating inflammation-related liver fibrosis [141].

4.2.2.2 Inorganic NPs activate the TGF-β signaling pathway

While NPs targeting TGF-β have outstanding tumor-suppressive effects, inorganic NPs can induce prometastasis and side effects by activating TGF-β signaling. Magdiel et al. demonstrated that nano-TiO2, which is universally added to food products, can promote EMT in colorectal carcinoma through both the TGF-β/MAPK pathway and the Wnt pathway (Figure 6B) [142]. Analogously, both silica NPs (nano-SiO₂) and hydroxyapatite NPs (nano-HA), which are commonly utilized as food additives, accumulate in colorectal cancer cells and induce an elongated fibroblast-like morphology. This morphological change is also capable of promoting EMT progression. This study revealed that EMT induction is not merely confined to nano-TiO₂ exposure but may represent a broader nanomaterial-induced phenomenon, indicating the possible toxicity and side effects of absorbable airborne nanomaterials in the induction of EMT progression. Similarly, nickel oxide NPs (Nano NiO) have been shown to induce EMT progression through TGF-β1/SMAD pathway in a hepatoblastoma-derived cell line (HepG2), resulting in hepatic fibrosis [143]. A similar tumor-promoting phenomenon has also been verified in another study investigating TiO₂ nanofibers. TiO2 nanofibers cause lung epithelial cells to obtain an aggressive tumor phenotype with upregulation of HIF-1α, TGF-β and N-cadherin, which serve as angiogenic, profibrotic and EMT markers, respectively [144].

Fe3O4 magnetic NPs (MNPs) arguably rank among the most extensively researched nanomaterials, particularly in cancer theranostics. Using PEI to guarantee MNPs colloidally stable in cell culture media, Man et al. constructed PEI-coated MNPs (PEI-MNPs), which served as a model to determine how the MNPs elicited cellular responses. PEI-MNPs led to tumor progression through the induction of autophagy and the activation of the TGF-β/ NF-κB signaling pathways via the generation of ROS [145].

Depending on many properties, including size, morphology, surface charge, chemical composition and other reactive properties, inorganic NPs might exhibit prometastatic effects and toxicity through TGF-β signaling. Zhu et al. reported that low-dose GO nanosheets with a large size range of 400-900 nm (GO-L) and a small size range of 200-600 nm (GO-S) similarly induced remarkable morphological and structural variations in the tumor cell membrane (Figure 6C), promoting tumor cell migration and invasion by activating TGF-β signaling and increasing the number of TGF-β receptors; although GO nanosheets induced cytotoxicity at relatively high doses [146]. GO activated TGF-β signaling to exert prometastatic effects in a dose-dependent manner. Another study revealed that small-sized (22 nm, 42 nm, and 71 nm) silver NPs (AgNPs) increase the expression of TGF-β, proinflammatory cytokines, and Th1-type and Th2-type cytokines in serum in a concentration-dependent manner and are more active at triggering toxicological or biological responses than large-sized AgNPs (323 nm) [147]. The results obtained by Park et al. proved that orally administered small-sized AgNPs were more capable of inducing organ toxicity and inflammatory responses than large-sized AgNPs were. Aluminum oxide (AlO) NPs are considered potential immunoadjuvants and drug delivery carrier materials. Manshian et al. demonstrated that wire-shaped AlO with a high aspect ratio, but not spherical-shaped AlO NPs, leads to tumor-associated inflammation and metastasis in animal models through the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and high expression of TGF-β [148]. All these findings indicate that the side effects of nanomaterials should be considered in the development of nanomedicines. The physicochemical properties of inorganic NPs (e.g., concentration, size, and morphology) are key factors influencing their effects on TGF-β. Future research should focus specifically on how changes in these physicochemical properties affect the bioactivity and safety of NPs.

4.2.3 Hybrid NPs

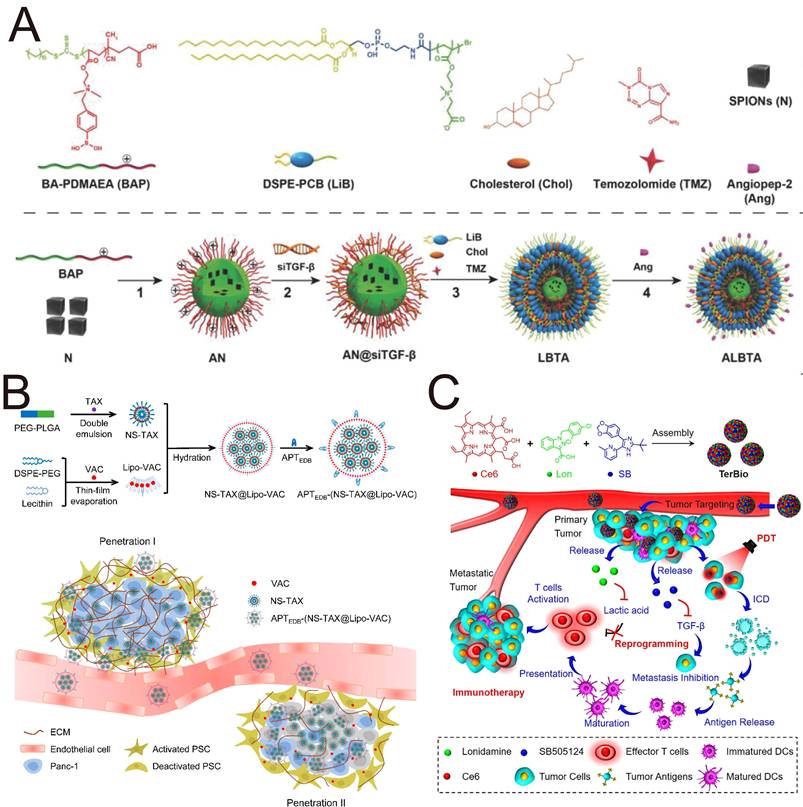

Owing to the combination of inorganic nanomaterials with organic nanomaterials, hybrid NPs with increased biocompatibility and suspension characteristics have garnered increasing attention in the development of versatile nanosystems for the delivery of TGF-β pathway antagonists (Table 4). Owing to their therapeutic and imaging abilities, controlled release, and versatility, hybrid nanosystems are promising for the theranostics of tumors.

The Janus-faced properties of inorganic NPs in the regulation of TGF-β signaling. (A) Inhibition of EMT by TiO2 NPs. Adapted with permission from [140]. Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society. (B) TiO2 NP-induced cell migration and invasion in intestinal epithelial cancer cells. Adapted with permission from [142]. Copyright 2018, John Wiley and Sons. (C) GO nanosheets promote cancer metastasis by promoting TGF-β signaling-dependent EMT. Adapted with permission from [146]. Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society.

Summary of hybrid NPs, lipid-polymeric NPs and small-molecule NPs targeting TGF-β for cancer treatment.

| Characteristic | TGF-β pathway antagonists | Nanoparticle/carriers | Cancer cell type | Model | Outcome | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid NPs | RLX | RLX-SPION | PANC-1 | Male CB17 SCID mice | RLX-2 conjugated SPIONs enhance the chemotherapeutic efficacy of GEM by inhibiting the differentiation of PSCs into CAF-like myofibroblasts. | [149] |

| Anti-TGF-β antibody | Anti-TGF-β and RGD2 conjugated Fe3O4/Gd2O3 hybrid NPs for delivery of sorafenib | MC38 | C57BL/6 mice | This MRI-guided nanosystem achieves synergistic effect of ferroptosis and TGF-β blockade. | [150] | |