13.3

Impact Factor

Theranostics 2026; 16(7):3697-3734. doi:10.7150/thno.126081 This issue Cite

Review

Targeting efferocytosis for tissue regeneration: From microenvironment reprogramming to clinical translation

1. Department of Plastic and Burn Surgery, Department of Radiology, Huaxi MR Research Center (HMRRC), Institution of Radiology and Medical Imaging, Rehabilitation Therapy, Institute of Breast Health Medicine, Frontiers Science Center for Disease-Related Molecular Network, State Key Laboratory of Biotherapy, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, China.

2. Psychoradiology Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province, Key Laboratory of Transplant Engineering and Immunology, NHC, and Research Unit of Psychoradiology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Chengdu 610041, China.

#These authors contributed equally: Yunzhu Li, Peiyu Li and Jiayi Song.

Received 2025-9-30; Accepted 2025-11-6; Published 2026-1-8

Abstract

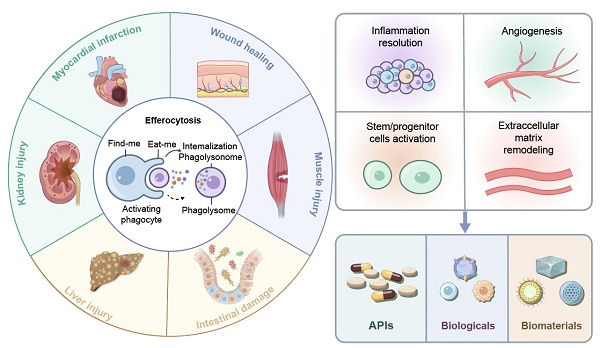

Efferocytosis, phagocytic clearance of apoptotic cells (ACs), is an essential biological process that resolves inflammation and regulates tissue regeneration in various organ systems. Through removal of apoptotic cell debris, efferocytosis attenuates secondary necrosis and dampens the release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). More importantly, it can reprogram phagocytes towards a pro-reparative phenotype via the secretion of anti-inflammatory mediators, metabolic rewiring, and the production of growth factors. There are four closely regulated stages in the entire process: “find-me” signal-mediated phagocyte recruitment, recognition of ACs via “eat-me” signals, AC internalization via Rho GTPase-dependent actin remodeling, and phagolysosomal degradation of ACs by either canonical or light chain 3 (LC3)-associated phagocytosis (LAP). In a repair context, efferocytosis may refer to the clearance of dying cells during various tissue repair processes, such as wound healing, liver injury, myocardial infarction, intestinal damage, kidney injury and muscle injury. Efferocytosis regulates inflammation resolution, stem/progenitor cell activation, extracellular matrix remodeling, and angiogenesis to coordinate tissue repair. Chronic pathology (e.g., diabetic ulcers, fibrosis) induced by dysfunctional efferocytosis results from accumulation of non-phagocytosed ACs that maintain inflammation and impair regeneration. Therapeutic strategies targeting dysfunctional efferocytosis have been developed, encompassing active pharmaceutical ingredients, biologics, and biomaterials-assisted therapeutic modalities. Despite promising outcomes from preclinical studies, challenges still exist in the spatiotemporal control and clinical translation of these therapeutic strategies. Future research could focus on the multi-omics integration and smart biomaterial development to dynamically modulate efferocytosis during different disease phases.

Keywords: efferocytosis, tissue regeneration, macrophage, inflammation resolution, biomaterials

1. Introduction

Tissue regeneration is a well-conserved process in evolution. When activated, the function/structure of damaged tissues are restored by switching on a series of cellular processes for regeneration, which involve damage sensing, immune modulation, progenitor cell mobilization, extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition and remodeling. This regeneration program is dampened in patients with chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Specifically, in terms of prevalent comorbidities, patients with type 2 diabetes, hypertension and coronary artery disease often exhibit pathological fibrosis or regenerative failure.

Efferocytosis or phagocytic clearance of apoptotic cells (ACs) is an essential process for maintaining tissue homeostasis by phagocytes [1,2]. Phagocytes can be classified into three groups: professional phagocytes (e.g., macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells (DCs)) with high phagocytic ability, nonprofessional phagocytes (e.g., epithelial cells, fibroblasts) with incompetent engulfment ability, and specialized phagocytes (e.g., Sertoli cells in testes) with both tissue-specific functions and phagocytotic ability [3]. Evidence has suggested that efferocytosis confers dual regenerative benefits after injury or disease progression: (1) preventing secondary necrosis and inflammatory damage from leaked cellular contents from ACs, and (2) reprogramming phagocytes into a pro-resolution phenotype through the secretion of anti-inflammatory mediators and the regulation of repair-promoting transcriptional pathways [4,5]. Unfortunately, impaired efferocytosis is often observed under chronic non-healing conditions, which results in the accumulation of secondary necrotic cells. The accumulation of necrotic cells perpetuates inflammatory cascades and simultaneously weakens pro-regenerative signals derived from ACs clearance in the tissue, creates a hostile microenvironment for tissue reconstruction [6-8].

The impact of the microenvironment created from efferocytosis on regenerative niches is rarely systematically elaborated and the effect of efferocytosis on key effector cells (e.g., stem cells, fibroblasts) is insufficiently elucidated in previous review articles [9]. We systematically examine mechanistic insights for efferocytosis in coordinating inflammation resolution with tissue regeneration through spatiotemporal metabolic reprogramming and intercellular crosstalk in this review article. We reveal mechanisms of efferocytosis in organ/tissue repair and highlight its dual role in chronic diseases including promoting tissue repair and driving pathological fibrosis under dysregulated conditions. After summarizing current efferocytosis-targeting strategies, we critically analyze barriers for targeting efferocytosis and provide our insights into future directions in addressing these barriers.

2. Efferocytosis processes and their regulation

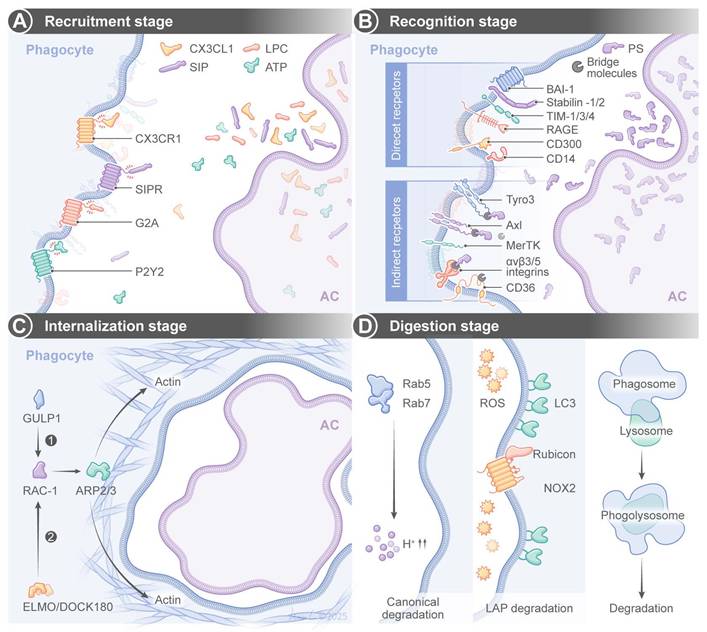

Efferocytosis is a tightly regulated multistep process, and it has a few key stages (Figure 1). The first stage is the “recruitment phase”, in which ACs release “find-me” signals to attract phagocytes via receptors such as CX3 C-chemokine receptor 1 (CX3CR1), G2 accumulation protein receptor (G2A), or P2Y purinoceptor 2 (P2Y2). The signals include chemokines (e.g., CX3 C-chemokine ligand 1(CX3CL1)/CX C-chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12)), lipids (e.g., sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P)/lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC)), or nucleotides (e.g., adenosine triphosphate (ATP)) [10-12]. The second stage is the “recognition phase”, in which “eat-me” signals from ACs (e.g., phosphatidylserine (PS), calreticulin) bind directly to phagocyte receptors (e.g., T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain (TIM) family, adhesion G protein-coupled receptor B1 (aDGrB1; also known as BAI1)) or indirectly to receptors like the Tyro3-Axl-MerKT (TAM) family or integrins via bridging molecules (e.g., growth arrest-specific gene 6 (Gas6), milk fat globule-epidermal growth factor 8 (MFG-E8)) [13-25]. Complementary to these pro-phagocytic signals, healthy cells actively maintain “don't-eat-me” signals to prevent inappropriate engulfment by phagocytes. CD47 is the most well-characterized don't-eat-me signal and it is a transmembrane glycoprotein that interacts with signal regulatory protein α (SIRPα) in phagocytes to deliver inhibitory signals through tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1/2, thereby suppressing phagocytosis [26]. CD24 is another “don't-eat-me” signal, and it binds to Siglec-10 on phagocytes to inhibit engulfment of aging neutrophils and cancer cells [27]. The dynamic balance between “eat-me” and “don't-eat-me” signals critically determine the efferocytosis efficiency under both normal physiology and diseased conditions.

The third stage is the internalization phase, in which receptor engagement activates Ras homologous guanosine-5'-triphosphatases (Rho GTPases) (e.g., Rac family small GTPase 1 (s)) via adaptors (e.g., engulfment and cell motility protein (ELMO), dedicator of cytokinesis 1 (DOCK180), engulfment adaptor PTB domain containing 1 (GULP1)) to trigger actin polymerization via actin-related protein 2/3 complex (ARP2/3) and WASP-family verprolin-homologous protein 1 (WAVE1), leading to the formation of a phagocytotic cup to engulf ACs [19,28-31]. Finally, in the digestion phase, phagosomes fuse with lysosomes to form phagolysosomes for enzymatic degradation of ACs via two pathways. The canonical degradation pathway involves phagosome maturation. Phagosomes mature via an increasingly acidic membrane-bound structure, such as Ras-related in brain protein 5 (Rab5) and Rab7 [32,33]. The other pathway is LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP). Class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3KC3), Rubicon, and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase 2 (NOX2)-generated reactive oxygen species (ROS) are actively engaged in LC3-lipidation [34-37].

3. Roles of efferocytosis in tissue repair

In addition to resolving cellular debris, efferocytosis facilitates tissue repair and regeneration by modulating the immune microenvironment, activating pro-regenerative programs, and coordinating remodeling of the ECM to restore tissue homeostasis through four closely connected steps: injury sensing, inflammation resolution, pro-regeneration cell activation, and ECM formation/remodeling [38]. 1) Injury sensing. Efferocytosis is primed by sensing apoptotic “find-me” signals to recruit macrophages toward injury sites. On the other hand, apoptotic cells also release PS as an essential “eat-me” signal on their surface [10,11]. This balancing signaling network enables apoptotic cells to be specifically recognized while protecting surrounding normal tissues from unnecessary immune stimulation. 2) Inflammation resolution. Efferocytosis attenuates pro-inflammatory environment by modulating macrophage metabolism. When engulfing apoptotic cells, macrophages switch to a metabolically oxidative state to drive the formation of multiple macrophage subpopulations with modulated pro-inflammatory (interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α)) and anti-inflammatory (mannose receptor C type 1 (CD206, or MRC1), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and Arginase 1 (Arg1)) markers [39,40]. 3) Pro-repair cell activation. Efferocytosis converts phagocytes into regenerative effector cells. Metabolites released by apoptotic cells (e.g., arginine, nucleotides) activate mechanistic targets of rapamycin complex 2 (mTORC2) signaling to promote macrophage proliferation and functional adaptation [41,42]. Moreover, efferocytotic macrophages also produce and release growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), which stimulate angiogenesis and fibroblasts to mediate connective tissue repair [43,44]. In addition to these functions, metabolic reprogramming in macrophages provides energy supply for stem cell niches and promotes stem cell proliferation [45]. Furthermore, efferocytosis directly activates stem cell differentiation through secreted factors, such as TGF-β and Wingless/INT-1 (Wnt) ligands, which prime lineage-specific programs [46]. Consistently, immunomodulatory molecules produced by stem cells (e.g., prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene 6 (TSG-6)) increase the ability of phagocytes to engulf apoptotic cells, thus amplifying the regenerative program [47]. 4) ECM formation and remodeling. Efferocytosis counteracts the dynamics of the ECM through a dual-role regulatory mechanism that promotes both matrix synthesis and matrix degradation. Efferocytotic macrophages release interleukin-1α (IL-1α) and osteopontin, which mediate fibroblasts activation for depositing and organizing fibrillar collagen into a provisional repair matrix [48]. Conversely, efferocytosis can also regulate collagen degradation and structural remodeling by reparative macrophages which are associated with source-level suppression of pro-fibrotic signaling after ACs resolution (Table 1) [49].

Core mechanisms and regulatory factors of efferocytosis in tissue repair.

| Stage/Key Process | Key Molecules /Axis | Function in Efferocytosis | Related Diseases | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recruitment phase | CX3CL1- CX3CR1 | Boosting MerTK-dependent efferocytosis due to CX3CR1 deficiency | HIRI | [99] |

| Coordinating endothelial cell migration and VEGF-mediated neovascularization | Skin wound healing | [73-75] | ||

| S1P-S1PR1 | Enhancing endothelial junction assembly through S1PR1-Rac1 signaling | Skin wound healing | [77-79] | |

| Promoting epithelialization by inducing keratinocyte differentiation through STAT3-mediated filaggrin expression | Skin wound healing | [83,84] | ||

| Recognition phase | PS | Exposing “eat-me” signal by apoptotic cells | Skeletal muscle injury | [192] |

| CCN1 | Bridging PS to αvβ3/αvβ5 integrins on phagocytes to facilitate efferocytosis by macrophages | Skin wound healing, liver injury | [55,123] | |

| MFG-E8 | Bridging PS to αvβ3/αvβ5 integrins on phagocytes to modulate debris clearance | Skin wound healing, dabetic wound, MI, IBD, intestinal IRI, skeletal muscle injury | [58,60,61,141,157,169-171,196] | |

| CRT | Binding to LRP to activate ERK/PI3K pathways and promote phagocytosis | Skin wound healing | [80,81] | |

| TIM-4 | Recognizing PS to promote KC efferocytosis | HIRI | [100] | |

| BAI-1 | Improving efferocytosis via ELMO1/DOCK1/RAC1 signaling | Colitis | [158] | |

| CD47-SIRPα | Blocking CD47-SIRPα to restore efferocytosis and improve recovery | Liver fibrosis, MI | [120,140] | |

| Digestion phase | ROS | Driving ADAM17-mediated MerTK cleavage, leading to apoptotic hepatocyte accumulation | HIRI | [116] |

| ANXA1 | Binding to FPR2/ALX on macrophages to activate AMPK signaling | Skin wound healing | [66-68] | |

| TREM2 | Enhancing efferocytosis via Cox2/PGE2-mediated Rac1 activation or PI3K-AKT activation | MASH, AKI, HIRI | [97,101,105,181] | |

| MerTK | Promoting efferocytosis and tissue repair | MI, diabetic cardiomyopathy, skeletal muscle injury | [93,136-139,199,200] |

Efferocytosis processes and their regulation. Efferocytosis is achieved through four sequential stages: (A) recruitment, (B) recognition, (C) internalization and (D) digestion. SIP sphingosine-1-phosphate, SIPR: sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor, LPC: lysophosphatidylcholine, ATP: adenosine triphosphate, PS: phosphatidylserine, BAI-1: brain angiogenesis inhibitor-1, TIM: T-cell immunoglobulin mucin, RAGE: receptorfor advanced glycation end products, GULP1: engulfment adaptor protein 1, ARP2/3 actin-related protein 2/3, ELMO/DOCK180: the complex of the engulfment and cell motility protein and the dedicator of cytokinesisprotein, ROS: reactive oxygen species, LC3: autophagy-related protein 1A/1B-light chain 3, NOX2: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase-2.

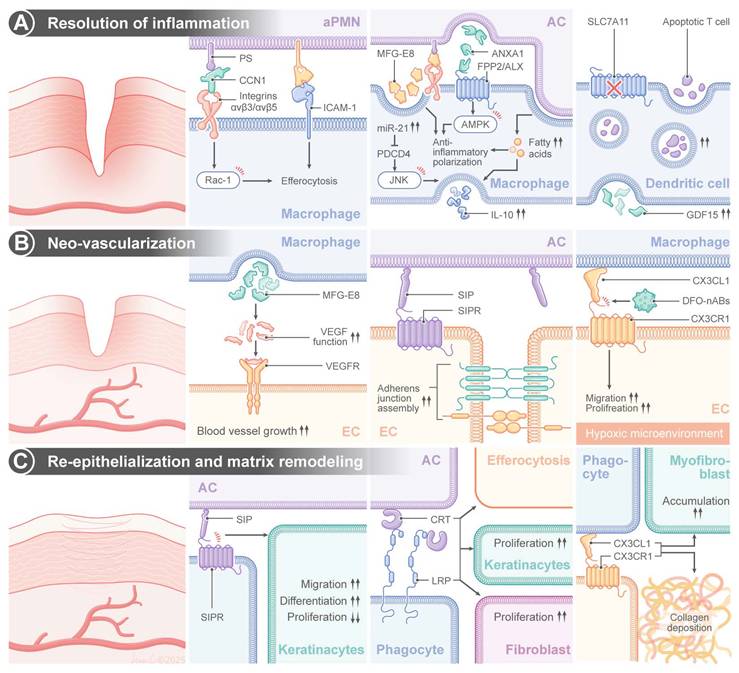

3.1 Efferocytosis in wound healing

Normal wound healing is a well-coordinated process consisting of four well-defined stages: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling [50,51]. When an injury occurs, neutrophils, the first line of recruited circulating leukocytes, arrive at the wound site and establish defenses against pathogens through the release of proteases and ROS [52,53]. Neutrophils are indispensable for killing invading pathogens; however, their massive influx into the wound bed is followed by a tightly regulated death of neutrophils through a process of efferocytosis [54]. Phagocytic scavenging of apoptotic neutrophils can prevent secondary necrosis and persistent inflammation during the resolution phase [54]. This process is regulated by a sophisticated molecular interplay between apoptotic neutrophils and macrophages. The matricellular protein, cellular communication network factor 1 (CCN1), has been identified as a regulator of this process. CCN1 can establish a bridge between PS, an evolutionarily conserved “eat-me” signal exposed on apoptotic neutrophils, and integrins αvβ3/αvβ5 on macrophage surface. Interaction between neutrophils and macrophages induced RAC1-dependent cytoskeletal remodeling, promoted phagosome formation and induced debris internalization [55]. Importantly, mechanical bridging is not the only function of CCN1, and it can regulate metabolic reprogramming of macrophages.

Macrophages display high levels of functional plasticity during wound healing, and their phenotype switches dynamically between pro-inflammatory M1 and anti-inflammatory M2 in a microenvironment-dependent manner [56]. Efferocytosis markedly modulates this polarization. Sequestration of apoptotic neutrophils supply macrophages with long-chain fatty acids that can be used to drive nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide positive (NAD+)-dependent metabolic pathways, thereby promoting oxidative phosphorylation and suppressing glycolysis. This change in metabolism upregulates interleukin-10 (IL10) expression through signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and potentiates M2 polarization while suppressing TNF-α expression through the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) [57]. The glycoprotein MFG-E8 can further amplify this switch by acting as a molecular glue that bridges PS on apoptopic cells and αvβ3/αvβ5 integrins on macrophages. Transcriptomic analyses have shown upregulation of MFG-E8 during skin repair, and we have recently demonstrated that debris clearance is defective, TNF-α/IL10 ratio is increased and wound healing is delayed in mice deficient for MFG-E8 (MFG-E8-/-) [58-60]. In addition to promoting phagocytosis, MFG-E8 directly triggers M2 polarization by activating phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT) signaling, thus promoting the production of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and enhancing fibroblast migration and collagen deposition [61]. In addition, neutrophil-derived intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) optimizes efferocytosis through the activation of the fibrinogen-mediated spleen tyrosine tinase (SYK) pathway in macrophages. It has been confirmed that a deficiency in ICAM-1 leads to the disruption of this crosstalk, a reduction in leukocyte infiltration and a delay in re-epithelialization in murine wounds [62-65]. Concurrently, apoptotic neutrophils release Annexin A1 (ANXA1), which binds formyl peptide receptor 2 (FPR2/ALX) on macrophages to activate adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling—a critical regulator of energy homeostasis. This interaction suppresses pro-inflammatory cytokine production and enhances the efferocytotic capacity through actin polymerization [66-68].

Efferocytosis induces epigenetic reprogramming in macrophages. Engulfment of apoptotic cells upregulates microRNA-21 (miR-21), which silences phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) and programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4) to enhance IL10 production and suppress the activities of pro-inflammatory cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) [69]. Clinically modified collagen gel (MCG) dressings have been demonstrated to accelerate diabetic wound healing by enhancing miR-21-c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)-IL10 signaling, reducing MMP-9-mediated matrix degradation [70]. The calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) on sensory neurons binds to the receptor activity modifying protein 1 (RAMP1) receptors on macrophages to boost neutrophil efferocytosis and macrophage VEGF production. Impaired healing has been found in a diabetic neuropathy model due to CGRP depletion, while engineered CGRP nanoparticles can restore the phagocytotic function and promote angiogenesis [71,72].

During the proliferative phase, efferocytosis drives angiogenesis through multiple mechanisms. CXCR2 and CX3CR1 chemokine receptors coordinate endothelial cell migration and VEGF-mediated neovascularization, while a deficiency in CX3CR1 impairs capillary growth [73-75]. Deferoxamine enhances vascularization by inducing the transcriptional activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1α) to promote VEGF secretion. Functionalized apoptotic body nanovesicles containing deferoxamine (DFO-nABs) are used to target hypoxic endothelium via CX3CL1/CX3CR1 signaling, promoting angiogenesis and accelerating wound closure in preclinical models [76]. MFG-E8 in synergy with VEGF can stabilize nascent vessels, and the sphingolipid mediator, S1P, enhances endothelial junction assembly through sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1PR1)-RAC1 signaling [77-79]. The immunomodulator, FTY720 (fingolimod), is utilized to enhance angiogenesis by reducing VEGF-induced vascular permeability [79].

Efferocytosis facilitates re-epithelialization and matrix remodeling. Chaperone calreticulin (CRT), an “eat-me” signal on the endoplasmic reticulum, can bind to LDL-receptor-related protein (LRP) on fibroblasts to activate ERK/PI3K pathways to drive keratinocyte migration [80,81]. Topical application of CRT, a typical “eat me” signal of efferocytosis, promotes macrophage migration, elevates the rate of reepithelialization, and enhances the rate and quality of wound healing in a diabetic murine model [82]. S1P promotes epithelialization by inducing keratinocyte differentiation through the expression of STAT3-mediated filaggrin, while FTY720 enhances collagen deposition via the activation of the mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 2/3 (SMAD2/3) [83,84]. Sonic Hedgehog (SHH), a member of the Hedgehog family and a secreted protein, binds to the patched receptor on target cells, activating the downstream transcription factor Gli [85]. SHH promotes M2 polarization and augments macrophage efferocytosis by enhancing OXPHOS of macrophages, ultimately contributing to collagen deposition [86].

Recent evidence indicates that impaired efferocytosis may significantly contribute to chronic wound pathogenesis especially in diabetic condition. In a genetically-modified diabetic mouse model, refractory skin wounds demonstrated increased apoptosis, inhibited endothelial cell proliferation, diminished fibroblast function and decreased procollagen I mRNA expression [87]. This pathologic condition is further prolonged by macrophage dysfunction since diabetic wounds demonstrated defective efferocytotic clearance of apoptotic cells. Khanna et al. have demonstrated that when impaired macrophage efferocytosis in diabetes, there will be an increase in the apoptotic cell burden and this leads to pro-inflammatory cascade with increased expression of TNF-α and IL-6 and a reduced level of IL10. This pro-inflammatory milieu further enhances inflammatory responses and greatly inhibits wound healing [60]. In addition, hyperglycemia-induced advanced glycation end products (AGEs) may also lead to the inhibition of phagocytosis. These glycated proteins/lipids preferably accumulate in diabetic tissues. The level of glycated proteins/lipids in diabetic tissues is inversely correlated with the macrophage phagocytic capacity in peritoneal models [87-90]. Mechanistically, AGEs bind to their receptor (RAGE) on M1 macrophages to lead to inhibition of phagocytosis. Treatment with anti-RAGE antibodies or soluble RAGEs (sRAGEs) restores macrophage function and improves neutrophil clearance and polarizes macrophages toward a pro-healing phenotype. Noteworthily, topical application of sRAGEs improves neo-vascularization and granulation tissue formation in diabetic wounds. Therefore, the AGE-RAGE signaling may be a potential target to heal diabetic wounds [91,92]. The glycation induced inhibition also have an impact on some critical efferocytosis mediators like MFG-E8. In diabetic wound environment, the protein level of MFG-E8 was down regulated. Hyperglycemia induced glycation further leads to the impairment of its PS binding capacity. Both of these lead to the defect in apoptotic cell clearance. Recombinant MFG-E8 (rMFG-E8) supplementation improved macrophage efferocytosis, angiogenesis and resolved inflammation to accelerate diabetic ulcer healing [60]. MicroRNA dysregulation also leads to diabetic wound pathology. Macrophage-derived miR-126 is a regulator that normally inhibits the expression of A disintegrin and metalloproteinase 9 (ADAM9) to maintain the efferocytosis efficiency. Under a high-glucose condition, miR-126 is suppressed, leading to overexpression of the ADAM9, which impairs apoptotic cardiomyocyte clearance, a phenomenon mirrored in human diabetic hearts characterized by impaired efferocytosis signaling. miR-126 overexpression has been demonstrated to enhance apoptotic cell clearance, and it could be a promising therapeutic approach for diabetes-impaired wound repair [93]. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ), a transcriptional regulator for the macrophage function, plays a dual role in wound healing. Injury normally induces upregulation of PPAR-γ to coordinate phagocytosis and inflammation resolution, while under a diabetic condition, sustained IL-1β expression can pronouncedly suppress the PPAR-γ activity. PPAR-γ knockout models display prolonged inflammation, reduced collagen deposition, and impaired angiogenesis due to accumulated apoptotic cells. Topical application of PPAR-γ agonists is demonstrated to accelerate healing in both normal and diabetic wounds by reactivating efferocytosis pathways [94-96]. In addition to macrophages, efferocytosis by DCs is compromised in diabetic wounds via dysregulation of the solute carrier family 7 member 11(SLC7A11). This cysteine-glutamate transporter critically governs DCs-mediated apoptotic cell clearance, and pharmacological inhibition of the transporter restores the efferocytotic capacity and improves diabetic wound treatment outcomes [97].

Recent studies have indicated that bacterial pathogenesis plays a role in delaying chronic wounds. Staphylococcus aureus-derived vesicles (SAVs) inhibit efferocytosis by activating the toll-like receptor 2-myeloid differentiation primary response 88-p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling (TLR2-MyD88-p38 MAPK) axis to promote cleavage of MerTK, a key efferocytosis receptor. The underlying mechanism is the culprit for the persistence of nonhealing SAV-infected wounds. Targeted inhibition of p38 MAPK is found to prevent MerTK degradation, restore efferocytosis and accelerate healing (Figure 2) [98].

3.2 Efferocytosis in liver injury

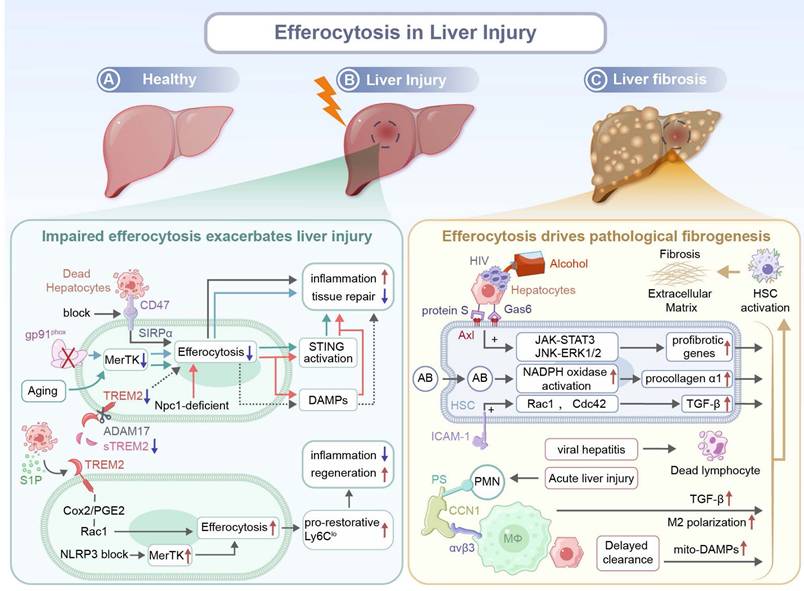

Liver injury represents a spectrum of pathological conditions characterized by hepatocyte death, sterile inflammation, and varying degrees of tissue remodeling. Efferocytosis plays an indispensable part in injured tissue repair by actively clearing apoptotic corpses. Beyond simple debris removal, it governs inflammation resolution, macrophage reprogramming, and fibrogenic signaling, dictating therapeutic outcomes of liver injury. Therefore, context-dependent cellular mediators often determine the effect of protection or pathogenesis induced by efferocytosis. Crucially, efferocytosis can be regulated to coordinate hepatic repair across injury paradigms, including hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury (IRI), metabolic/alcoholic damage, and toxic insults, by modulating inflammation and promoting tissue regeneration.

Efferocytosis in cutaneous wound healing. Efferocytosis play a critical role in regulating wound healing by (A) promoting the resolution of inflammation, (B) supporting neo-vascularization and (C) enhancing reepithelialization and matrix remodeling. CCN1: cellular communication network factor 1, ICAM-1: intracellular adhesion molecule-1, AC: apoptotic cell, aPMN: apoptotic polymorphonuclear neutrophils, MFG-E8: milk fat globule-epidermal growth factor 8, mi-R21: microRNA-21, ANXA1: Annexin A1, IL-10: interleukin-10, GDF15: growth differentiation factor-15, EC: endothelial cell, VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGFR: vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, DFO-nABs: nanovesicles containing deferoxamine, CRT: calreticulin, LRP: LDL-receptor-related protein, JNK: c-Jun N-terminal kinase, AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase.

In models of hepatic IRI, multiple molecular pathways for the promotion of apoptotic cell clearance have been identified. A deficiency in CX3CR1 amplifies C-C chemokine receptor type 1/5 (CCR1/5)-mediated macrophage migration and liver X receptor α (LXRα)-mediated MerTK-dependent efferocytosis, thus repopulating the Kupffer cell (KC) niche via reparative macrophages reprogramming and facilitating IRI resolution. Pharmacological inhibition of CX3CR1 via an antagonist, AZD8797, attenuates hepatic IRI severity, confirming it could be a therapeutic target [99]. In addition, Ming et al. have identified T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein 4 (TIM-4) as a critical regulator for efferocytosis and KC homeostasis. TIM-4, a PS receptor, promotes KC efferocytosis by suppressing pro-inflammatory TNF-α production and upregulating the secretion of anti-inflammatory IL10 upon Toll-like receptor activation. A deficiency in TIM-4 compromises the efferocytosis capacity of KCs, leading to aggravated hepatocellular injury in the early phase and impaired resolution of inflammation in the later phase [100]. During the hepatic IRI inflammation resolution phase, TREM2 in pro-resolution macrophages facilitates the recognition and internalization of ccumulated apoptotic cells via COX2/PGE2-mediated RAC1 activation. Efferocytosis drives phenotypic transition of monocyte-derived macrophages into reparative CX3CR1+Ly6Clo, which orchestrates inflammation resolution and promotes liver regeneration [101]. It has been confirmed that Resolvin D1 (RvD1), a pro-resolving lipid mediator, confers protection against hepatic IRI, and the protective effect is ascribed to enhancements in M2 polarization and efferocytosis via lipoxin A4 receptor/formyl peptide receptor 2 (ALX/FPR2) activation [102]. Interestingly, for the first time, the anti-inflammatory and pro-regenerative effects of netrin-1, a neuroimmune guidance cue, on hepatic IRI are revealed, supporting the role of neuroimmune molecules in a non-neural system. Netrin-1 may serve as a therapeutic target for hepatic IRI. Attenuating injury and promoting liver regeneration can be achieved through exogenous administration of netrin-1 or modulation of its signaling pathway [103].

In chronic liver injury models, including alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD) and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), efferocytosis also plays a pivotal role. In alcohol-induced liver injury models, RvD1 promotes macrophage efferocytosis of apoptotic hepatocytes and enhanced clearance of dead hepatocytes mitigates hepatic damage, thus RvD1 could be used as a therapeutic adjuvant to support liver regeneration through anti-inflammatory repair [104]. The hepatocyte-derived S1P signal via S1PR1 upregulates the expression of TREM2, a phagocytotic receptor on infiltrated macrophages, to achieve efficient efferocytosis of lipid-laden apoptotic hepatocytes, maintain tissue immune homeostasis and prevent MASH development. Nevertheless, prolonged hypernutrition triggers TNF/IL-1β-mediated ADAM17-dependent proteolytic cleavage of TREM2, thus depleting functional soluble TREM2 (sTREM2). This loss impairs efferocytosis, leading to aberrant accumulation of apoptotic debris, which contributes to chronic liver inflammation and MASH progression [105,106]. Furthermore, bioinformatics and machine learning analysis of human liver transcriptomes reveal that efferocytosis impairment is induced through upregulated TREM2 and downregulated TIM-4, leading to polarization towards an M1 phenotype and reduction in the M2 population, which drive unresolved inflammation. Notably, TREM2/TIM-4 signatures have been used to precisely diagnose MASH, suggesting their clinical use for early diagnosis and stratification of the disease [107]. To treat toxic insults such as acetaminophen-induced injury, natural antibodies (NAbs) are used to drive the phagocytosis of necrotic hepatocytes via the Fc gamma receptor (FcγR) and integrin alpha M (CD11b) to fuel liver regeneration. NAbs supplementation enhances the efferocytotic capacity and increases the hepatic density, providing therapeutic benefits [108].

The identity and phenotype of efferocytotic macrophage subsets are critical for the outcome of therapeutic modalities for liver injury. Macrophage efferocytosis of hepatocyte debris induces the formation of a restorative matrix-degrading Ly6Clo phenotype with activated ERK signaling, which promotes the resolution of tissue fibrosis. Inducing efferocytosis using liposomes expands the population of this restorative macrophage phenotype in vivo to accelerate liver fibrosis regression [109]. Proteomic analysis confirms that Ly6CloCX3CR1hi macrophages display an enriched level of several reparative efferocytosis-related proteins, including arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase (ALOX15), a marker associated with inflammation resolution and tissue repair. The macrophage subpopulation directly accelerates hepatocyte proliferation via the secretion of hepatocyte growth factors (HGFs). Moreover, selective depletion of this subpopulation hinders liver regeneration, confirming the essential role of this subpopulation in efferocytosis-driven liver repair [110,111]. In addition, both in vitro and in acetaminophen (APAP)-treated mice, the secretory leucocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI), a microenvironmental mediator, has been shown to reprogram myeloid cells for resolution responses by inducing the formation of a pro-restorative MerTK+HLA-DRhigh phenotype. This phenotype displays enhanced efferocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils to promote liver regeneration [112]. The STAT3-IL10-IL6 autocrine-paracrine pathway has been identified as a positive regulator of macrophage efferocytosis and phenotypic conversion, and this pathway plays a critical role in disposal of apoptotic bodies and tissue repair. Disruption of this axis results in defective clearance of apoptotic cells, impaired macrophage reprogramming, and delayed resolution of liver injury, while IL-6 treatment restores the phagocytic function and improves regenerative outcomes [113]. Mechanical cues also modulate these activities. Upregulation of the mechanosensitive ion channel Piezo1 in macrophages during hepatic fibrosis enhances their stiffness-dependent efferocytosis. Consistently, macrophages without Piezo1 exhibit sustained inflammation and impaired spontaneous resolution of liver fibrosis, whereas pharmacological activation (e.g. Yoda1) of Piezo1 alleviates fibrotic progression [114].

Efferocytosis-driven tissue remodeling is not limited to hepatocyte contexts. After bile duct decompression, apoptotic cholangiocytes are efficiently cleared by recruited macrophages via efferocytosis, and these macrophages are reprogrammed into a fibrolytic phenotype. The efferocytosis-induced transition is marked with robust upregulation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which mediate ECM degradation. Concurrently, the removal of dying cholangiocytes suppresses profibrotic signaling, promoting coordinated inflammation resolution and tissue remodeling [115].

Impaired efferocytosis exacerbates inflammation and fibrosis after liver injury. Aging exacerbates hepatic IRI by impairing MerTK-mediated macrophage efferocytosis. Excessively produced ROS drives ADAM17-mediated MerTK cleavage, leading to the accumulation of apoptotic hepatocytes. Subsequently, DNA from dying hepatocytes activates stimulator of interferon genes (STING) signaling in macrophages, contributing to sustained inflammation and tissue injury in aged livers [116]. Besides, it has been demonstrated that the NOD-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome hinders liver regeneration and inhibits hepatocyte proliferation through impairing MerTK-mediated efferocytosis by macrophages and preventing subsequent polarization of macrophages toward a pro-reparative Ly6Clo phenotype. Pharmacological inhibition of NLRP3 via MCC950 effectively restores the efferocytotic capacity and promotes liver regeneration after 70% partial hepatectomy in mice fed with a high-fat diet [117]. Similar defects associated with MerTK are found in ALD. A deficiency in gp91phox, a catalytic subunit in NOX2, impairs hepatic efferocytosis by macrophages, which is attributed to downregulated expression of key phagocytotic receptors including MerTK and TIM-4. The deficiency in the catalytic subunit results in the accumulation of apoptotic cells and prevents programming of macrophages from a pro-inflammatory to a tissue-restorative phenotype, elevating the severity of ALD and inhibiting hepatic tissue repair [118]. Moreover, in patients with alcoholic hepatitis (AH), neutrophil-derived neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) exacerbate liver injury and resist efferocytosis by macrophages that are chronically exposed to alcohol. The persistence of NETs induces macrophages pro-inflammatory differentiation, sustaining tissue damage. Transcriptomic analysis has identified that an elevated level of CD47 expression on low-density neutrophils (LDNs) from AH patients is coupled with PS downregulation, jointly impairing neutrophil clearance. The neutrophil-macrophage dysregulation intensifies NET-driven inflammation and hinders liver repair [119]. In MASH, necroptotic hepatocytes displayed an upregulated level of CD47, while liver macrophages exhibit an increased level of SIRPα expression, collectively impairing efferocytosis. Blocking the CD47-SIRPα axis restores efferocytosis of necroptotic hepatocytes by macrophages and ameliorates liver fibrosis [120].

Macrophages with a deficiency in myeloid Niemann-Pick C1 (NPC1), a lysosomal cholesterol transport protein, exhibit a diminished capacity in the degradation of apoptotic cargoes like mitochondrial DNA, leading to excessive DAMPs accumulation, aggravated hepatic inflammation, and STING/NFκB pathway activation. Inefficient efferocytosis hinders macrophage reprogramming toward a reparative phenotype and intensifies liver fibrosis, thereby impairing tissue regeneration [121]. Miyazaki et al. have demonstrated that the absence of fatty acid binding protein 7 (FABP7), exclusively localized in KCs, impairs efferocytosis primarily due to downregulated expression of the scavenger receptor CD36. The defect leads to deteriorated liver injury and a reduction in the levels of TNF-α, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and TGF-β1. Consequently, FABP7-deficient mice exhibit insufficient fibrogenic responses during chronic liver injury [122].

Emerging evidence has suggested that under a pathological condition, maladaptive efferocytosis may paradoxically drive fibrosis through the activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). Macrophages typically reprogram toward a pro-resolving phenotype upon uptake of apoptotic cells, while HSCs, the key fibrogenic cells in the liver, exhibit profibrotic transformation after a distinct response to engulfed apoptotic materials. Early in the injury response, CCN1 facilitates efferocytosis by liver macrophages through bridging PS on apoptotic cells and integrin αvβ3 on phagocytes, which triggers the polarization of macrophages towards an M2-like phenotype that expresses fibrogenic TGF-β1. Besides, efferocytosis has been demonstrated to induce HSC transdifferentiation into myofibroblast-like cells, contributing to fibrosis development in chronic liver injury [123]. Canbay et al. have demonstrated that in bile duct-ligated mice, KC efferocytosis of apoptotic hepatocytes enhances Fas Ligand (FasL)/TNF-α expression, amplifying a feed-forward loop of hepatocyte apoptosis. This process drives hepatic fibrosis via cytokine storm production, neutrophil infiltration, and HSC activation. Inhibition of KCs or hepatocyte apoptosis attenuates these effects, suggesting there is a pathogenic link between efferocytosis and liver injury [124]. Another study has indicated that efferocytosis of apoptotic bodies (ABs) by HSCs directly triggers liver fibrosis through upregulation of procollagen α1 and TGF-β1. The upregulation of procollagen α1 may activate nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase, resulting in excess superoxide production. Therefore, efferocytosis could be as a key mechanism for converting physiological removal of debris into pathological fibrogenesis [125].

Pathogen-associated or metabolite-induced ABs exacerbate the maladaptive response. After ABs from hepatocytes are exposed to the alcohol metabolite, acetaldehyde, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), these Abs are engulfed by HSCs via Axl with the help of two bridging molecules, Gas 6 and protein S. This efferocytosis process triggers ROS-dependent JNK-ERK1/2 and janus kinase (JAK)-STAT3 pathways, leading to enhanced expression of profibrotic genes and HSC activation [126]. Muhanna et al. have uncovered a novel fibrogenesis pathway. HSCs engulf disease-associated lymphocytes, particularly CD8+ T cells, leading to their activation. The activation is mediated via ICAM-1/integrin αV interaction through RAC1 and cell division control protein 42 (CDC42) signaling pathways. Efferocytosis of lymphocytes enhances α-SMA expression and TGF-β signaling in HSCs, aggravating injury and strengthening fibrosis while suppressing regeneration in patients with chronic viral hepatitis [127].

Importantly, delayed or inefficient clearance of apoptotic hepatocytes by professional phagocytes such as macrophages may indirectly promote HSC activation. The prolonged presence of uncleared apoptotic hepatocytes induces continuous release of mitochondria-derived DAMPs, which directly activate HSCs to drive progression of liver fibrosis independent of classical inflammation pathways. The experimental data has supported that both defective and misdirected efferocytosis leads to intensified fibrosis (Figure 3) [128].

3.3 Efferocytosis in myocardial repair

Myocardial injury, particularly myocardial infarction (MI), initiates a complex repair process characterized by dynamic inflammatory resolution, cardiomyocyte repopulation, and fibrotic remodeling. The poor regenerative ability of cardiomyocytes and the inflammatory milieu have been identified as critical barriers for ventricular remodeling and heart regeneration, and cardiac healing becomes more challenging than superficial wound healing [129-131].

Post-MI cardiac repair progresses through three overlapping phases: inflammation, proliferation, and maturation, and the repair process is mediated by dynamic interactions among neutrophils, macrophages, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, cardiomyocytes, and stem cells through paracrine signaling and cell-cell communication [132,133]. After IRI, necrotic cardiomyocytes release DAMPs to trigger rapid neutrophil infiltration. Effective clearance of these neutrophils in the injury site is critical to prevent secondary necrosis and prolonged inflammation [134,135]. Efferocytosis, phagocytic clearance of apoptotic cells including cardiomyocytes and neutrophils, serves as a pivotal mechanism to resolve inflammation and coordinate tissue regeneration in the infarcted heart. Dysregulated efferocytosis, however, drives pathological fibrosis and chronic inflammation [132].

Central to this process is MerTK, a key efferocytosis receptor with a context-dependent role in disease pathogenesis. While genomic studies have revealed the protective or detrimental effect of MerTK during pathogenesis, its specific role in MI repair has been recently clarified [136]. Wan et al. have demonstrated dynamic upregulation of MerTK in the left ventricular ischemic zone peaks on day 7 post-MI, thus macrophages can efficiently clear apoptotic cardiomyocytes. This MerTK-dependent efferocytosis process suppresses secondary necrosis, facilitates inflammation resolution, and promotes tissue regeneration, supporting there is a direct mechanistic link between apoptotic cell clearance and inflammatory-to-reparative transition [137]. The reparative potential of MerTK is demonstrated in an ischemia-reperfusion model. Cleavage-resistant MertkCR reduces the production of soluble MerTK (solMER), enhances phagocytosis, and improves therapeutic outcomes. Resident major histocompatibility complex class II/low expression C-C chemokine receptor type 2 (MHCIILOCCR2) macrophages drive this repair process through TGF-β secretion, while recruited monocytes intensify MerTK cleavage via proteolytic inactivation. Therapeutic CCR2 blockade preserves MerTK integrity, and it could be a promising strategy to mitigate reperfusion injury [138]. Interestingly, cardiomyocyte debris impairs efferocytosis by inducing MerTK shedding through cardiomyocyte smacrophage crosstalk. Despite macrophage chemotaxis and apoptotic CM binding, poor engulfment of apoptotic cells is observed due to cardiomyocytes-triggered proteolysis of the extracellular domain of MerTK. Genetic stabilization of the MerTK cleavage site can partially restore the phagocytic capacity, suggesting MerTK may be a critical factor for cardiac injury resolution [139]. In contrast to a pro-repair role of MerTK, injured cardiomyocytes upregulate CD47, a “don't eat me” signal. The signal binds to SIRPα on macrophages to suppress efferocytosis. The interaction between CMs and macrophages perpetuates inflammation and exacerbates injury, while acute CD47 blockade leads to improved infarct resolution and functional recovery. The balance between “eat me” (e.g., MerTK) and “don't eat me” (e.g., CD47) signals has a critical impact on repair outcomes, and they could be therapeutic targets for efferocytosis regulation [140].

Roles of efferocytosis in liver injury and fibrosis. (A) In a healthy liver, apoptotic cell clearance maintains immune tolerance and tissue integrity. (B) During liver injury, impaired efferocytosis caused by CD47 blockade, MerTK deficiency, TREM2 downregulation, aging, or Npc1 mutation leads to reduced uptake of apoptotic cells, enhanced STING activation, DAMP release, persistent inflammation, and impeded repair. In contrast, signals, such as S1P, Cox2/PGE2, and Rac1, promote the generation of pro-restorative Ly6Clo macrophages and tissue regeneration. CD47: cluster of differentiation 47, MerTK: Mer receptor tyrosine kinase, TREM2: triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2, Npc1: Niemann-Pick type C1, STING: stimulator of interferon genes, DAMPs: damage-associated molecular patterns, S1P: sphingosine-1-phosphate, Cox2: Cyclooxygenase-2, PGE2: Prostaglandin E2, Rac1: Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1, Ly6Clo: Lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus C low. (C) During liver fibrosis, efferocytosis of apoptotic hepatocytes induced by alcohol, viral hepatitis, or HIV activates hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) through Axl/Protein S/Gas6 signaling. The signaling pathway triggers the activation of JAK-STAT3, JNK-ERK1/2, and NADPH oxidase pathways, resulting in TGF-β release, profibrotic gene induction, and collagen deposition. Additional mechanisms, including ICAM-1-mediated interactions, CCN1/αvβ3 signaling, M2 polarization, and delayed apoptotic cell clearance, promotes extracellular matrix accumulation and fibrogenesis. HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus, HSCs: Hepatic stellate cells, Axl: AXL receptor tyrosine kinase, Gas6: Growth arrest-specific 6, JAK-STAT3: Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription 3, JNK-ERK1/2: c-Jun N-terminal kinase-extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2, NADPH: Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, Cdc42: Cell division cycle 42, TGF-β: Transforming growth factor-beta, ICAM-1: Intercellular adhesion molecule 1, PS: Phosphatidylserine, PMN: Polymorphonuclear neutrophil, CCN1: Cellular communication network factor 1, αvβ3: Integrin alpha-v beta-3, MΦ: Macrophage, mito-DAMPs: Mitochondrial damage-associated molecular patterns.

Emerging evidence supports that cardiac debris clearance can be achieved by other cell types in addition to macrophages. Myofibroblasts exhibit a high phagocytic capacity through MFG-E8-dependent mechanisms. They secrete anti-inflammatory TGF-β, while inhibiting IL-6 production to create a pro-reparative microenvironment [141]. In addition, TIM-4+ resident macrophages uniquely mediate PS recognition and apoptotic cell clearance through the PS receptor. The depletion of TIM-4+ resident macrophages impairs the cardiac function although compensatory macrophages are recruited to replace TIM-4+ resident macrophages, suggesting an indispensable role of TIM-4+ resident macrophages in inflammation resolution [142].

Efferocytosis is significantly impacted by cellular metabolism. In diabetic cardiomyopathy, hyperglycemia disrupts the miR-126/ADAM9/MerTK axis, impairing macrophage efferocytosis and impeding myocardial repair [93]. By contrast, TREM2+ macrophages can perform efferocytosis after metabolic adaptation through the SYK-SMAD4 pathway. The downregulation of the engulfment-induced solute carrier family 25 member 53 (SLC25A53) disrupts mitochondrial NAD+ transport, enhancing itaconate production to suppress cardiomyocyte apoptosis and promote fibroblast proliferation. The metabolic shift suggests there is a tight integration between the phagocytic function and cellular metabolism during a repair process [143]. Another unique metabolic pathway associated with efferocytosis is recently revealed. Neonatal cardiac injury activates C1q+TLF+ macrophages through MerTK-dependent efferocytosis, and arachidonic acid metabolism is redirected to thromboxane A2 (TXA2). TXA2 binding to cardiomyocyte G-protein-coupled thromboxaneprostanoid receptors triggers glycolytic reprogramming and regenerative repair mediated by Yes-associated protein 1/transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif (YAP/TAZ) [144].

Key molecular regulators have been gradually identified from different experimental models. Macrophage-derived legumain (LGMN) enhances LC3-II-dependent phagosome formation and activates calcium signaling to accelerate apoptotic cell clearance, reduce IL-1β/TNF-α release and improve post-MI remodeling [145]; TGF-β-activated SMAD3 promotes MFGE8-mediated efferocytosis and activates PPAR-γ/δ anti-inflammatory signaling, while a deficiency in SMAD3 leads to ineffective clearance of apoptotic cells and hindered remodeling [146]; Neutrophil-secreted neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) polarizes macrophages toward an M2 phenotype with elevated MerTK expression and an enhanced efferocytotic capacity [147]; Galectin-3hiCD206+ macrophage-derived osteopontin (OPN) enhances efferocytosis through IL10-STAT3 signaling, which is critical for reparative fibrosis and ventricular stability [148]; Neogenin 1 (NEO1) can maintain the efferocytotic capacity by suppressing JAK1-STAT1-mediated proinflammatory polarization [149].

Profiling the cellular landscape during cardiac repair reveals functional specialization of macrophage subsets. Embryo-derived MHC-IIhi macrophages maintain tissue homeostasis through constitutive efferocytosis, while bone marrow-derived MHC-IIlo macrophages play a vital role in post-MI necrotic debris clearance. Therapeutic targeting of these distinct subpopulations could achieve optimized inflammation resolution and tissue regeneration [150]. Notably, CD36 on the recruited Ly6chi monocytes initiates the nuclear receptor subfamily 4 group A member (NR4A1)-MerTK signaling cascade that drives macrophage maturation and repair programming [151].

In contrast to the pro-repair mechanisms, pathological matrix remodeling creates barriers for efferocytosis. The accumulation of high molecular-weight hyaluronan (HAHMW) in infarcted hearts physically impedes phagocytosis by macrophages through CD44-independent mechanisms, particularly in naive (M0) and pro-inflammatory (M1) macrophage subsets. The suppression of efferocytosis delays inflammation resolution, sustains IL-17/IP-10 signaling, and promotes maladaptive remodeling through persistent autoantigen exposure. Therefore, manipulation of biophysical properties of HA, or modulation of the ECM composition could improve the phagocytic efficiency [152].

Paradoxically, excessive activation of efferocytosis may be detrimental in the chronic injury context. A deficiency in the G protein-coupled receptor, class C, group 5, member B (GPRC5B) enhances macrophage efferocytosis through blocking E prostanoid receptor 2 (EP2 receptor) signaling and reducing cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-mediated anti-inflammatory responses. While macrophage efferocytosis is beneficial for bacterial clearance to prevent infections, it induces imbalanced macrophage polarization in MI, enhancing myeloid cell recruitment but exacerbating inflammation and fibrosis. These findings suggest the context-dependent role of efferocytosis. It is essential for acute injury resolution, while it may be disruptive during chronic tissue repair when it is improperly regulated (Figure 4A) [153].

3.4 Efferocytosis in intestinal injury

The intestinal mucosa is characterized by a high proliferative capacity. It is a dynamic interface, and epithelial homeostasis is maintained through timely efferocytosis after it is exposed to various types of injury stress. Recent evidence has suggested that efferocytosis is pivotal in repairing diverse intestinal injury types, including the inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), chemically induced colitis, intestinal IRI, and radiation-induced enteropathy. Efficient efferocytosis not only prevents secondary necrosis and mitigates the release of pro-inflammatory intracellular contents but also actively shapes the resolution of inflammation and promotes tissue regeneration.

In murine models of dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colitis, the G2A deficient mice exhibit aggravated colitis, evidenced by the heightened disease activity, colon shortening and histopathological deterioration. In the G2A deficient mice, fewer CD4+ lymphocytes are recruited to the inflamed colon and more TNFα+ that is secreted by pro-inflammatory monocytes in an eosinophil-dependent manner is released, leading to impaired efferocytosis [154].

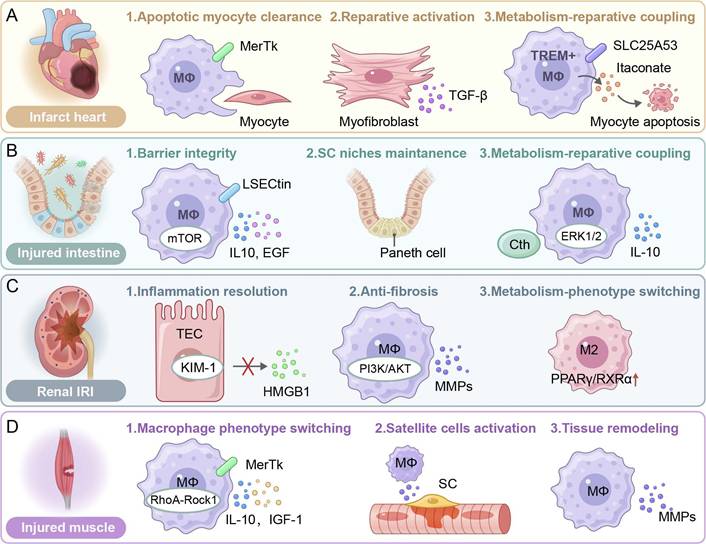

Roles of efferocytosis in the injury of the heart, intestine, kidney and muscle. (A) Infarct heart. Apoptotic myocyte clearance via MerTk receptor signaling; reparative activation of myofibroblasts through TGF-β secretion; metabolic coupling via SLC25A5353-mediated transport or TREM⁺ macrophage-derived itaconate. (B) Injured intestine. The barrier integrity is maintained via LSECtin/mTOR and IL-10/EGF pathways; the stem cell niche supports through Paneth cell interactions; metabolism-repair coupling is mediated by ERK1/2/IL-10 and Cth. (C) Renal IRI. Inflammation resolution via the KIM-1/TEC axis and HMGB1 modulation; anti-fibrotic effects through PI3K/AKT/MMPs signaling; M2 polarization driven by PPARγ/RXRα transcriptional activation. (D) Injured muscle. Phenotype switch of macrophages (MΦs) via RhoA-Rock1 mechanotransduction; satellite cell (SC) activation by IL-10/IGF-1 paracrine signaling; tissue remodeling facilitated by MMPs and recurrent MerTk-dependent clearance. SLC25A53: Solute carrier family 25, member 53. LSECtin: Lymphatic endothelial cell lectin, mTOR: Mammalian target of rapamycin, IL-10: Interleukin-10, EGF: Epidermal growth factor, Cth: Cystathionine gamma-lyase, ERK1/2: Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2. TEC: Tubular epithelial cell, KIM-1: Kidney injury molecule-1, HMGB1: High mobility group box 1, PI3K: Phosphoinositide 3-kinase, AKT: Protein kinase B, MMPs: Matrix metalloproteinases, PPARγ: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, RXRα: Retinoid X receptor alpha. RhoA: Ras homolog family member A, Rock1: Rho-associated kinase 1, IGF-1: Insulin-like growth factor-1, SC: Satellite cell.

More recently, growing evidence has suggested that the effects of efferocytosis on ameliorating intestinal inflammation are pronounced during the recognition phase. It has been shown that the C-type lectin receptor, LSECtin, on macrophages contributes to the engulfment of apoptotic cells by macrophages. Additionally, LSECtin induces the expression of anti-inflammatory/tissue repair factors in an engulfment-dependent manner, such as TGF-β, VEGF, and heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor (HBEGF), which in turn stimulates epithelial cell proliferation and promotes intestinal epithelium regeneration [155]. Furthermore, apoptotic cells modulate intracellular signaling dynamics by enhancing the interaction between LSECtin and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), thereby strengthening LSECtin-mediated activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) in macrophages. Subsequently, the heightened mTORC1 activity orchestrates transcriptional upregulation of anti-inflammatory/tissue repair factors, including IL10 and HBEGF. These mediators expedite intestinal regeneration by synchronizing epithelial restitution with inflammation resolution to restore tissue homeostasis [156]. In both DSS- and 2,4,6 trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS)-induced colitis models, the colons of animals receiving recombinant human MFG-E8 (rhMFG-E8) exhibit significant attenuation of neutrophil infiltration, downregulation of pro-inflammatory mediators, and a decrease in the apoptotic cell counts. These findings collectively demonstrate that rhMFG-E8 ameliorates DSS- and TNBS-induced colitis and promotes regeneration, supporting its potential as a therapeutic agent for IBD [157]. Ravichandran et al. have found that BAI1 deficiency augments colitis severity by impairing efferocytosis after acute intestinal injury. Conversely, transgenetically boosting the BAI1 expression improves apoptotic cell clearance via ELMO1/DOCK1/RAC1 signaling, attenuates inflammation, and facilitates epithelial repair in murine DSS-induced colitis models. Critically, intestinal epithelial-specific BAI1 augmentation is sufficient in mitigating the pathological burden and accelerating mucosal regeneration [158]. The absence of COX-2 in macrophage aggravates IBD progression by disrupting reparative efferocytosis. Meriwether et al. have demonstrated that COX-2 bolsters the macrophage phagocytotic capacity and triggers phenotypic reprogramming, enhancing intestinal epithelial repair. COX-2 deletion impairs the engulfment of apoptotic neutrophils, which may be due to a reduction in the binding affinity, while macrophage polarization is skewed away from an efferocytosis-competent transcriptional profile. Mechanistically, COX-2 regulates the synthesis of efferocytosis-associated lipid mediators, including prostaglandin I2 (PGI2), PGE2, lipoxin A4 (LXA4), and 15-Deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 (15d-PGJ2), and these lipid mediators can also impact secondary efferocytosis [159,160]. Additionally, the ablation of CD300f, a phosphatidylserine receptor that recognizes apoptotic intestinal epithelial cells (IECs), exacerbates the pathogenesis of IBD. In murine colitis models, CD300f on DCs as professional phagocytes is essential for maintaining gut immune homeostasis. The CD300f-deficient mice exhibit impaired DSS resolution although these mice have hyperactive phagocytotic activity. Paradoxically, CD300f-/- DCs are induced to overexpress TNF-α, which subsequently drives aberrant IFN-γ production by colonic T cells and perpetuates gut inflammation [161].

In the internalization phase of efferocytosis, ChemR23, a pro-resolving G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) overexpressed on neutrophils and macrophages in therapy-refractory IBD, drives pathological neutrophil accumulation, leading to failure in inflammation resolution. An agonistic anti-ChemR23 monoclonal antibody (mAb) can bind to overexpressed ChemR23, mimicking resolvin E1 signals through ERK/Akt pathways to promote macrophage efferocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils, accelerate recovery from acute inflammation, and prevent fibrosis [162].

In the digestion phase, the activation of the homodimeric erythropoietin receptor (EPOR) on macrophages creates an anti-inflammatory microenvironment for tissue regeneration by enhancing efferocytosis, which may be dependent on LAP. Besides, EPOR activation remarkably promotes the production of anti-inflammatory/tissue repair factors including TGF-β, MRC1, chitinase-like protein 3 (YM1), PPAR-γ, MerTK and CD36, which are essential for apoptotic cell engulfment. ARA290, an erythropoietin (EPO) derivative, has been identified to orchestrate the restoration of the intestinal barrier function through upregulation of the expression of Mucin 2 (MUC2), a goblet cell mucin and augmentation of mucus secretion, partly by promoting the production of TGF-β [163]. Another study suggests that nuclear receptor binding factor 2 (NRBF2), a regulatory subunit of the autophagy-related PI3KC3 complex, is critical in promoting efferocytosis and resolving intestinal inflammation [164]. Additionally, LXR-deficient mice are susceptible to colitis induction. The LXR expression is reduced in the colonic tissues of IBD patients. Pharmacologic activation of LXR in colonocytes suppresses NF-κB and MAP kinase signaling via ATP-binding cassette transporter subfamily A member 1 (ABCA1), reducing pro-inflammatory chemokines (e.g. IL-8, C-C motif chemokine ligand 28 (CCL)-28) and promoting resolution of inflammation. The anti-inflammatory milieu may support efficient efferocytosis by inhibiting excessive immune activation, thereby facilitating tissue repair [165,166]. Besides, PPAR-γ activation effectively ameliorates IBD progression by orchestrating the regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), AGE/RAGE signaling, and cellular senescence pathways [167].

The SuperMApo (SUPERnatant collected from Macrophage APOptotic cell culture) is enriched in pro-resolving factors produced by macrophages after efferocytosis, including several chemokines (CCL5, CXCL2, and CCL22) and cytokines (IL-1RA, IL10, and TGF-β). The SuperMApo hinders progression of IBD by mitigating intestinal inflammation and promoting mucosal healing. Specifically, the SuperMApo suppresses inflammatory cell infiltration into colitis lesions. It also triggers the activation of wound healing in fibroblasts and IECs, which is supported by their enhanced proliferative and migratory properties [168].

Intestinal IRI is an acute injury characterized by massive epithelial apoptosis in the intestinal mucosa and its associated lymphoid tissues followed by an intense sterile inflammatory response. Massive epithelial apoptosis elevates the burden for efferocytosis, while enhanced efferocytosis through MFG-E8 and metabolic enzymes becomes critical for inflammatory resolution [169]. In an established animal model of intestinal IRI, the intestinal level of MFG-E8 is significantly reduced. Enhancing apoptotic cell clearance by supplementing rmMFG-E8 suppresses systemic inflammatory responses, attenuates intestinal injury, and promotes VEGF-mediated tissue repair [170,171]. Cystathionine gamma-lyase (Cth) is an enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of cystathionine into cysteine, α-ketobutyric and ammonia, which are intermediate metabolites involved in H2S production. Cth has been shown to affect the intestinal function by promoting the synthesis of H2S to treat colitis [172,173]. Moreover, Cth activates macrophage efferocytosis via the ERK1/2 signaling pathway through the production of H2S both in vivo and in vitro, which in turn regulates intestinal inflammation and promotes intestinal mucosal repair. Pharmacological inhibition of Cth or ERK1/2 impairs mucosal repair, while agonists for Cth or ERK1/2 can accelerate the mucosal recovery. Clinically, the Cth level is positively correlated with the efferocytosis activity and the level of inflammation resolution, and a higher Cth level results in faster barrier recovery in patients [174].

Interestingly, using irradiation mice models and intestinal organoids, Shankman et al. have discovered a novel role of Paneth cells in phagocytic clearance of apoptotic IECs. Paneth cells residing in intestinal crypts can act as phagocytes, and enhancing their efferocytosis may offer novel therapeutic strategies to alleviate mucosal injury in the contexts of chemotherapy or chronic IBD because unresolved apoptosis in these contexts exacerbates tissue damage, impairs the innate immunity, and disrupts the stem cell niche in the crypt (Figure 4B) [175].

3.5 Efferocytosis in kidney injury

Renal tissues injured by ischemic or toxic insults display acute tubular epithelial cell (TECs) degeneration, basement membrane disruption, interstitial inflammation, and occasional glomerular mesangial expansion. In mild acute kidney injury (AKI), surviving TECs dedifferentiate, migrate, and proliferate to repopulate the tubular epithelium, however, severe injury leads to persistent epithelial loss, capillary rarefaction, and progressive fibrosis due to ECM deposition. Efferocytosis is a central mechanism in orchestrating the balance between inflammation and repair after renal tissue injury. Both TECs and macrophages play a part in this dynamic and staged process. TECs are the predominant cell type during the early injury phase, while macrophages are essential in the later stages. Effective coordination between these cell types helps maintain tissue homeostasis, whereas impairment in efferocytosis leads to prolonged inflammation, maladaptive repair, and fibrosis [176].

Upon injury, an early biomarker of AKI, kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1), is upregulated in dedifferentiated TECs. KIM-1 is a phosphatidylserine receptor that enables recognition of apoptotic cells and oxidized lipids and promotes their engulfment. The epithelial clearance mechanism initiates local resolution by reducing the release of DAMPs and dampening pro-inflammatory signaling. KIM-1 activation triggers phosphorylation events to recruit the PI3K p85 subunit and activate the PI3K/AKT cascade, which in turn inhibits IκB kinase (IKK)/NF-κB signaling and reduces the production of TNF-α, IL-6, and MCP-1. Concurrently, ERK/MAPK signaling promotes epithelial migration and proliferation, facilitating tissue repair [177,178]. In addition, properdin, secreted by TECs, supports efferocytosis by promoting autonomous uptake of apoptotic debris by TECs, reducing the release of DAMPs like High Mobility Group Box 1, and attenuating inflammatory responses. In the properdin-deficient mice, efferocytosis by TECs is impaired, leading to enhanced apoptosis and impaired renal function in an IRI model [179].

As the injury progresses and the initial epithelial response wanes, macrophages become the principal phagocytic population. Macrophages transition into a reparative (M2-like) phenotype, and they clear apoptotic cells, degrade excess ECM via MMPs, and secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL10. These activities help resolve inflammation and promote TECs proliferation, angiogenesis and tissue regeneration, thereby preventing irreversible glomerular damage and facilitating renal repair [180]. TREM2, an upstream immune-regulatory receptor, plays a crucial role in efferocytosis. By activating the PI3K/AKT pathway, TREM2 enhances the clearance of apoptotic cells by macrophages and suppresses the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6), ultimately mitigating the progression from AKI to chronic kidney diseases. Overexpressed TREM2 on macrophages can improve survival and promote repair, while a deficiency in TREM2 exacerbates inflammation, leading to increased fibrosis and tubular atrophy [181]. Additionally, V-domain Ig suppressor of T cell activation (VISTA), an immune-checkpoint molecule that is predominantly expressed on macrophages, simultaneously enhances macrophage efferocytosis of apoptotic cells and suppresses excessive T-cell activation. During the repair phase after renal ischemic injury, VISTA-positive resident macrophages accelerate tissue recovery through this dual mechanism of debris clearance and immunosuppression [182].

Kidney fibrosis results from maladaptive repair due to repeated or severe injury in which the normally self-limiting wound-healing program becomes chronic. In addition to repeated or severe injury, kidney fibrosis stems from disruption in the phagocytic crosstalk, and the failure in efferocytosis converts a self-healing process into a fibrosis process to form a matrix-laden scar. A few molecules have been identified as inhibitors of effective efferocytosis, leading to exacerbated kidney injury and progression to fibrosis. For instance, junctional adhesion molecule-like protein (JAML), which is upregulated on macrophages during AKI, promotes the conversion of macrophages into a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype with a reduced efferocytosis capacity. Therefore, upregulation of JAML prolongs tissue damage by preventing efficient clearance of apoptotic cells and perpetuating inflammation. In the JAML-/- mice, JAML deficiency attenuates inflammatory responses by impeding the infiltration of macrophages and neutrophils and reducing the level of proinflammatory mediators in the kidney from the mice with renal IRI [183]. Additionally, microRNAs, such as miR-126, have been shown to impair efferocytosis by inhibiting the PI3K/insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1)/focal adhesion kinase (FAK) signaling pathway and promoting M1 polarization. Impaired efferocytosis accelerates the fibrotic process by inhibiting the anti-inflammatory and reparative roles of macrophages [184]. The macrophage receptor CD36 can facilitate apoptotic cell clearance, paradoxically, CD36 also promotes fibrosis by activating oxidative fibrogenic signaling pathways during chronic kidney injury. CD36 triggers NADPH-oxidase-dependent ROS production and subsequent activation of the TGF-β/Smad and NF-κB pathways. The oxidative burst skews macrophages toward a profibrotic M2-like phenotype, stimulates myofibroblast differentiation, and accelerates ECM accumulation during chronic kidney injury [185].

All lupus nephritis (LN) patients demonstrated overwhelming tubulointerstitial injury in the acute inflammatory period, with clear tubular necrosis and acute inflammatory cell infiltration. In this sense, the acute phase of LN could also be viewed as a type of AKI. Defective efferocytosis participates in the immunopathogenesis of LN. Impaired efferocytosis of macrophages result in the persistent accumulation of apoptotic bodies in the renal tissue and the formation/deposition of immune complexes in glomeruli. The accumulated immune complexes cause complement activation and amplify the local inflammation and induce extra renal injury. Molecular basis of defective clearance includes downregulated expression of scavenger receptors and impaired regulation of PPAR-γ/retinoid X receptor α (RXRα) signaling pathways in macrophages. PPAR-γ/RXRα signaling pathways are a transcriptional program that normally drives the engulfment machinery [186]. In LN, metabolic support for efferocytosis is also compromised. Carnitine palmitoyl transferase (CPT1a), a key enzyme located on the outer mitochondrial membrane, is essential for the metabolic state and function of macrophages, such as their polarization profile and efferocytotic activity. When the CPT1a level in macrophages is sufficiently low, macrophages do not have adequate fatty-acid-oxidation (FAO)-derived energy, their efferocytosis capacity is reduced, and apoptotic debris accumulates, thereby intensifying inflammation in LN [187]. Additionally, enhanced activation of the tonicity-responsive enhancer-binding protein (TonEBP), a transcription factor highly responsive to osmotic stress and inflammatory signals, exacerbates inflammation in LN by inhibiting efferocytosis and simultaneously enhancing antigen presentation, perpetuating autoimmune responses [188]. Conversely, enhancing macrophage-mediated clearance pathways, such as LC3-associated efferocytosis, can attenuate autoimmunity and improve outcomes. Furthermore, therapeutic modulation of the macrophage function through exosomal microRNAs, such as miR-16 and miR-21 derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), has shown promising outcomes by shifting macrophages towards an anti-inflammatory, pro-efferocytotic phenotype. These macrophages efficiently clear apoptotic debris and promote regulatory T-cell recruitment (Figure 4C) [189].

3.6 Efferocytosis in skeletal muscle injury

Skeletal muscle is one of the few adult mammalian tissues that can restore its structure and rehabilitate the contractile performance after substantial injury. Muscle regeneration is characterized by a well-coordinated sequence of events that involves immune cell infiltration, necrotic fiber clearance, activation of satellite cells (SCs), and remodeling of the extracellular matrix. At the core of this regenerative process are SCs, the paired box protein 7 (PAX7)-positive muscle stem cells, which reside beneath the basal lamina of each myofiber. In a healthy muscle, they are mitotically quiescent sentinels, but within hours of injury they receive biochemical and mechanical cues and they are driven through a tightly choreographed cascade of events: activation, clonal expansion, lineage commitment, terminal differentiation into myoblasts, and ultimately fusion either with each other or with existing myofibers. This cascade is essential for re-establishing intact, multinucleated fibers capable of generating force. It is noted that during this cascade of events, SCs are governed by a transient but highly organized inflammatory milieu dominated by macrophages, while the function of macrophages is controlled by efferocytosis [190]. The interweaving relationship between efferocytosis and SC biology is pivotal to manipulating skeletal-muscle repair.

The regenerative process is conventionally divided into three overlapping phases—degeneration/inflammation, regeneration, and remodeling. A laceration, toxin injection, or an ischemic insult causes local myofiber necrosis and vascular leakage, thereby releasing DAMPs to trigger complement activation and endothelial adhesion-molecule expression. Neutrophils swiftly arrive at the injured site. They execute valuable debris clearance and antimicrobial tasks, while their persistence is harmful for muscle regeneration. Timely removal of apoptotic neutrophils is crucial. Roughly 12-24 h post-insult, Ly6Chi/CCR2+ monocytes respond to the CCL2 gradient generated from both injured fibres and resident immune cells. Lu et al. have shown that CCL2 expression is essential for both monocytes and the muscle, and CCL2 gradient triggers effective recruitment of monocytes into the injured site, and subsequent secretion of macrophage-derived insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), a trophic factor that directly stimulates SC expansion. The M1-like macrophages, the first wave of recruited cells, secrete TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, nitric oxide (NO), and MCP-1, collectively activating quiescent SCs, up-regulating the myogenic differentiation 1/myogenic factor 5 (MyoD/MyF5), and driving SCs proliferation [191].

To engulf apoptotic neutrophils and necrotic fibre fragments, macrophages sense external PS via multiple receptor systems. Recognition of “eat-me” signals (e.g., external PS) on dying cells re-wires the signaling network in macrophages, reprogramming their transcriptome toward an anti-inflammatory, M2-like phenotype. This transition plays a vital role in productive muscle healing since persistent inflammation, fibrotic deposition, and functional decline are often associated with the presence of the M1-like macrophages. An array of receptor-ligand pairs mediate PS sensing, while the TAM family tyrosine kinases, including Tyro3, Axl, and especially MerTK, play a dominant role in skeletal muscle. Up-regulation of Mer coincides with the phenotype M1-to-M2 conversion; a deficiency in MerTK hinders apoptotic-cell clearance and prolongs the cytokine storm, ultimately stalling SC-driven myogenesis [192]. Intracellularly, AMPKα1, an energy sensor protein regulating cellular energy metabolism, play a role in phagocytic signaling. The deletion of AMPKα1 in myeloid cells inhibits efferocytosis-induced M2 polarization and markedly delays the regeneration process [193]. In addition to these kinase pathways, the Ras homolog family member A-Rho-associated coiled-coil-containing protein kinase 1 (RhoA-ROCK1) signaling axis controls the formation of the phagocytic cup by regulating cytoskeletal dynamics. Inhibition of this pathway paradoxically enhances efferocytosis and induces the production of the nuclear factor I X (NFIX), a transcription factor, which in turn reinforces the M2 transcriptional signature. The deletion of NFIX in myeloid cells locks macrophages into an inflammatory phenotype and induces defective SC differentiation [194].

Upon the completion of efferocytosis, macrophages are transformed into a trophic factory. Their secretome orchestrates the subsequent SC fate. Growth differentiation factor-3 (GDF3) and IGF-1 act in synergy to accelerate myoblast alignment and fusion, thus promoting the expansion of regenerating fibers. TGF-β and IL-10 resolve residual inflammation, and they mitigate excessive proliferation of SCs, steering the SC progeny toward quiescence to replenish the stem-cell pool [195]. Specific pro-resolving lipid mediators, such as Resolvin D1 (RvD1), bind to G-protein-coupled receptors to boost efferocytosis and transform macrophages toward a CD206+/Ly6Clo phenotype. Markworth et al. have demonstrated that systemic RvD1 not only accelerates neutrophil clearance but also helps the growth of regenerated fibers and the generation of the contractile force. The performance of these lipid mediators is heavily dependent on opsonins like MFG-E8, which provide a bridge between PS on apoptotic bodies and integrins on phagocytes. The retinol saturase (RetSat)-MFG-E8 axis is a great example of the opsonins. Macrophages without RetSat barely produce MFG-E8 and engulf fewer apoptotic bodies, consequently, the M2 polarization is not activated. SCs may be able to sense the deficiency in the cytokine and initiate compensatory actions, but the niche remains sub-optimal, yielding smaller, mis-aligned fibers and patchy ECM [196]. Additionally, transglutaminase 2 (TG2) acts as a PS co-receptor to facilitate apoptotic-cell tethering and an intracellular cross-linker to promote myoblast fusion. Inside differentiating myogenic cells, TG2 establishes cross-links between ECM proteins and fusogenic factors. Therefore, in TG2-null mice, the majority of apoptotic bodies are initially cleared, while the release of the downstream growth differentiation factor 3 (GDF3) and the myotube fusion are compromised, yielding thinner, weaker fibers, which indicates that TG2 has a dual role in macrophage signaling and myogenic cell morphogenesis [197].