13.3

Impact Factor

Theranostics 2026; 16(7):3735-3770. doi:10.7150/thno.124671 This issue Cite

Review

Contemporary opportunities and potential of Auger electron-emitting theranostics

1. Department of Nuclear Medicine, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1881 East Rd, Houston, TX 77054, USA.

2. Cyclotron Radiochemistry Facility, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1881 East Rd, Houston, TX 77054, USA.

3. RADIATE Radiopharmaceutical Research and Development Platform, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1881 East Rd, Houston, TX 77054, USA.

Received 2025-9-4; Accepted 2025-12-20; Published 2026-1-14

Abstract

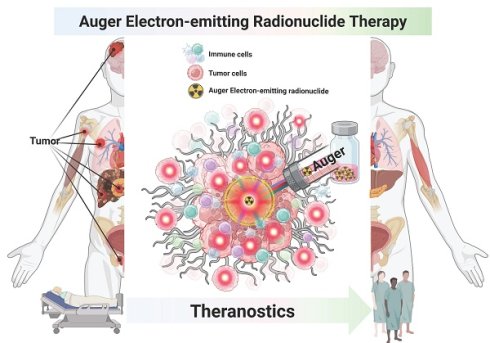

Recent breakthroughs in radiopharmaceutical (RP) therapy have emerged interest in employing Auger electron (AE)-emitting radionuclides as potential agents for precise theranostics. AE provides energy with exceptional localization due to their short tissue penetration range (TPR, < 10 nm), rendering them particularly effective for targeting nuclear DNA in tumor cells. In this context, AE-emitting radionuclide therapy (AE-emitting RLT) enables the targeted destruction of tumor cells while reducing harm to adjacent healthy tissue, a significant challenge in this field. Preclinical and early clinical investigations reveal the efficacy of AE-emitting RLTs in the theranostics of diverse malignancies, such as glioblastoma, prostate cancer, and neuroendocrine tumors. Notwithstanding these developments, challenges and limitations persist regarding dosimetry, delivery efficiency, and the treatment of radiotoxicity. A new paradigm is being developed to tackle the obstacles encountered by integrating molecular target markers (e.g., PARP) that function near the nucleus to improve the intranuclear delivery efficiency of AE-emitting radionuclides. Novel radiochemical methods such as these have facilitated the more stable and efficient labeling of biomolecules with AE-emitting radionuclides. Also, recent advances in DNA-molecular targeting, nanoparticles, nucleic acid/protein engineering, click- or bioorthogonal conjugation chemistry, and artificial intelligence (AI)-based structure modeling present concrete opportunities to overcome these limitations. Moreover, the integration of diagnostic imaging companion platforms employing theranostic radioisotope pairings facilitates real-time assessment of therapeutic efficacy and biodistribution, resulting in the formulation of enhanced treatment regimens. This review summarizes the prior development, recent advancements, barriers in clinical implementation, and future perspective of AE-emitting RLTs.

Keywords: theranostics, Auger electron-emitting radionuclide therapy, radiopharmaceuticals

1. Introduction to Theranostics

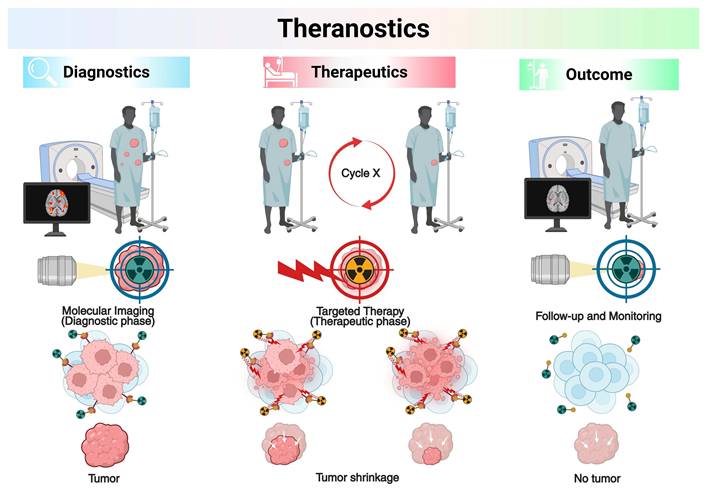

Theranostics represents an evolving paradigm in precision medicine that integrates diagnostic imaging and radioligand therapy (RLT), also known as targeted radionuclide therapy (TRT), using matched pairs of radiopharmaceuticals (RPs) labeled with diagnostic and therapeutic radionuclides [1, 2]. This conceptual framework facilitates the validation of the existence and condition of biological targets via molecular imaging, followed by therapeutic intervention based on those findings [3]. The primary function of theranostics is to identify candidates for RLT through imaging of the identical molecular target [4]. The selection of patients usually includes clinically validated indicators and molecular biomarkers found in the target tissues. Theranostic strategies differ from traditional methods by first administering a radiolabeled diagnostic agent, enabling in vivo visualization of target expression through supplementary imaging modalities, followed by therapeutic intervention utilizing a chemically compatible compound labeled with a therapeutic radionuclide [5]. TRT uses diagnostic radionuclides that give off gamma (γ-) photons or positrons (β+) to show where molecular targets are in real time within pathological lesions. Therapeutic radionuclides that emit alpha (α-), beta (β-), or Auger electrons (AE) can be used as substitutes for these diagnostic radionuclides to deliver targeted cytotoxic effects [6, 7]. This diagnostic-therapeutic capability not only identifies patients likely to benefit from treatment before therapy but also allows for quantitative assessment of biodistribution, supports personalized treatment planning, and facilitates post-treatment dosimetric evaluation [8, 9]. The combination of targeted RPs with other treatments, like external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) or immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), has made it possible to treat patients with advanced or treatment-resistant cancers in new ways. The key point is regulatory milestones have accelerated clinical translation: [177Lu]Lu-DOTATATE (Lutathera®, Novartis) was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on January 26, 2018, for somatostatin receptor-positive gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs) [10, 11], [68Ga]Ga-PSMA-11 (Locametz®, Novartis) was approved on December 1, 2020, for prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA)-positive prostate cancer imaging [12, 13]; and [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 (Pluvicto®, Novartis) was approved on March 23, 2022, for PSMA-positive metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) [14, 15]. The latter has established itself as the first blockbuster RP in the history of nuclear medicine. These milestones highlight the capacity of theranostics to provide personalized medicine by individualizing the therapeutic index for each patient, achieving an exact equilibrium between efficacy and safety (Figure 1).

The β-emitting radionuclide [177Lu]Lu- possesses favorable physical/chemical properties that have contributed to its broad clinical use; however, these same features can also induce off-target organ and bone marrow toxicity, ultimately restricting the amount of radioactivity that can be administered safely [16]. Section 2 elaborates extensively on the physical features of therapeutic radionuclides. Conversely, researchers are investigating α-emitting radionuclides for application in several cancer types, including mCRPC, due to their ability to selectively eradicate tumor cells while minimizing damage to adjacent healthy tissues [16]. AE-emitting radionuclides offer an added advantage: they demonstrate enhanced focused cytotoxicity at the single-cell level and greater localized energy relative to β-emitting radionuclides. These properties position AEs as a promising option for malignancies that are refractory to other treatments or for metastatic disease with a microscopic tumor burden [17]. Although numerous preclinical studies have demonstrated the potent biological effect/efficacy of AEs, ongoing early-phase (phase I/II) clinical trials remain preliminary yet noteworthy [18-22]. To date, however, no AE-emitting RLT has achieved widespread clinical adoption.

Illustration of theranostics with radiopharmaceuticals (RPs) pairs. Created with BioRender.com.

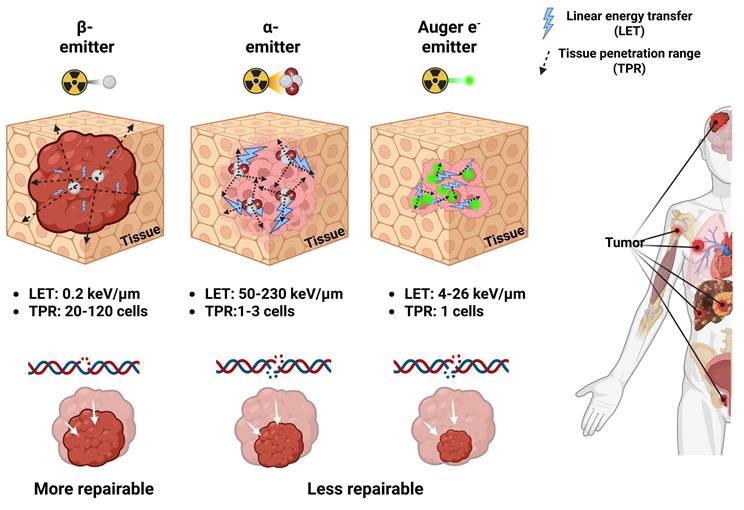

Schematic comparison of properties of β-, α-, and AE-emitting RLTs. Low LET radiation from β-emitting radionuclides primarily causes DNA single-strand breaks (DNA SSBs), which are repairable but can result in cell death when repair fails by DNA repair systems. The high TPR of β-particles increases the risk of off-target toxicity in nearby normal tissues and bone marrow. Conversely, α- and AE-emitting radionuclides deliver high LET radiation that induces irreparable DNA double-strand breaks (DNA DSBs), and their shorter TPR enables highly localized single cell levels cytotoxicity with minimal injury to adjacent healthy tissues. Created with BioRender.com.

We summarize the therapeutic mechanisms, including microdosimetry, of widely used β- and α-emitting radionuclides alongside AE-emitting radionuclides. We also provide the current chemical limitations preventing widespread realization of AE-emitting RLTs and various potential mitigation strategies to overcome them. We critically present prior development efforts, including both successful and failed studies, to highlight barriers hindering clinical translation. Furthermore, this review overviews existing and promising suitable/potential pairs of AE-emitting radionuclides for companion diagnostics imaging and suggests a perspective for the future of AE-emitting RLTs.

2. Mechanism of Therapeutic Radionuclides in Nuclear Medicine

Depending on the emission characteristics of the radionuclide, RPs may serve either diagnostic or therapeutic purposes. Photon emissions such as X-rays, γ-rays, and positrons are primarily employed for imaging and target verification, whereas β-particles, α-particles, and AE (Figure 2) mediate therapeutic effects. A clear understanding of the nature of each type of radiation and its corresponding biological mechanism is critical, as the selection of an appropriate therapeutic approach may vary significantly depending on these factors.

2.1 β-particles

β-particle emission is a type of radioactive decay that occurs in nuclei with an excess of neutrons over protons. During this process, a neutron is converted into a proton, releasing a high-energy electron, a β-particle, and an antineutrino [23]. These β-particles have tissue penetration ranges (TPR) that are relatively long, commonly involving 0.5 and 12 mm (the same as the diameter of about 20 to 120 cells). They also emit low linear energy transfer (LET) radiation with values between 0.1 and 1.0 keV/μm [24]. This property allows β-emitting radionuclides to induce cytotoxicity within tumors by generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) and causing predominant DNA single-strand breaks (DNA SSBs) [25]. Such DNA damage is relatively minor compared with the DNA double-strand breaks (DNA DSBs) induced by α-/or AE-emitting radionuclides, which release higher linear energy. DNA damage caused by the low LET of β-emitting radionuclides is more amenable to repair, but if the repair process fails, it may ultimately lead to apoptotic cell death (Figure 2). β-emitting radionuclides are especially beneficial for treating tumors with different types of target expression due to the "crossfire-effect." It occurs when radiation from targeted cells extends to adjacent non-targeted or weakly expressing cells, rendering treatment more effective in solid tumors [26, 27]. [90Y]Y-, [131I]-, and [177Lu]Lu- belong to several β-emitting radionuclides that have been approved for clinical use [28]. In particular, the FDA-approved RPs Lutathera® and Pluvicto® utilize [177Lu]Lu- to deliver TRT [29, 30]. [177Lu]Lu-, with a half-life of 6.7 days, emits γ-photons at 113 keV and 208 keV, enabling high-quality single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging alongside β-particles with a maximum energy of 497 keV, making it especially well-suited for theranostics applications [31]. However, its relatively low LET and longer TPR may increase the risk of damaging adjacent healthy tissues. In this context, α-emitting radionuclides have attracted interest in their ability to deliver highly localized, powerful cytotoxic effects with low off-target toxicity, especially in the treatment of small-volume or micro-metastatic illness, including inside bone marrow compartments [32].

2.2 α-particles

Radionuclides that undergo α-decay emit out α-particles, which are composed of two protons and two neutrons (helium-4 nuclei). These particles have high LET values between 50 and 230 keV/μm. Even though their TPR ranges from 20 to 100 μm, which is only 1 to 3 cell diameters, the high LET makes it possible for an immense amount of energy to be deposited along the particle path [33, 34]. This results in complex and often irreparable DNA DSBs, contributing to pronounced cytotoxic effects compared to β-emitting radionuclides (Figure 2) [35, 36]. α-emitting RLT is especially advantageous in the treatment of micrometastatic lesions or hematologic malignancies, where radiation can be confined to targeted cells with minimal exposure to adjacent normal tissue [37, 38]. The primary α-emitting radionuclides being studied are [211At]At-, [212Bi]Bi-, [212Pb]Pb-, [213Bi]Bi-, [223Ra]Ra-, [225Ac]Ac-, and [227Th]Th- [39]. Of the above, [223Ra]RaCl₂ (Xofigo®) is the only FDA-approved treatment. It was approved in 2013 for mCRPC with bone involvement [40, 41]. Novel therapies, including [225Ac]Ac-PSMA-617, have shown much promise in phase I clinical trials (AcTION, NCT04597411). Approximately fifty percent of the patients with mCRPC who received the therapy had a clinically significant drop in their prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels, and early data suggest that it may also improve overall survival. [225Ac]Ac-PSMA-617 may be an improvement over β-emitting radionuclide-based treatments like [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-617 (Pluvicto®) [42]. Nonetheless, the production of α-emitting radionuclides remains constrained by high costs and a lack of infrastructure for making them [43]. Moreover, the recoil of daughter isotopes during decay cascades may result in systemic redistribution, leading to possible toxicities in non-target organs [44, 45]. These limitations necessitate innovative solutions in radionuclide production, chelator development, and biological containment of decay progeny.

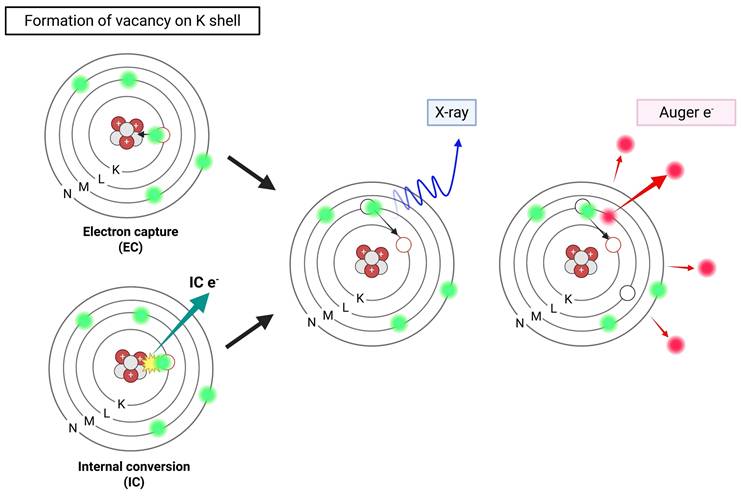

2.3 Auger Electrons

Certain radionuclides often employed in nuclear medicine imaging undergo decay via electron capture (EC) or internal conversion (IC), resulting in the emission of a cascade of low-energy electrons known as AEs. In EC, a proton-rich nucleus assimilates an inner-shell electron, often from the K shell. This changes a proton into a neutron and leaves a vacant space in the electron orbital. As an electron from a higher energy shell (e.g., L shell) fills this vacancy, excess energy is released either as a characteristic X-ray or transferred to another electron, which is then ejected from the atom—this ejected electron is termed an AE [46]. In parallel, IC occurs when an excited nucleus de-excites by transferring its excess energy directly to an orbital electron, ejecting it from the atom instead of emitting a γ-photon (Figure 3) [47]. Most AEs possess relatively low energies, typically below 26 keV, with a maximum reported at 78.2 keV (e.g., from [195Pt]Pt-), but exhibit extremely short TPR, often under 0.5 µm. This behavior corresponds to a high LET ranging between 4 and 26 keV/μm, significantly exceeding that of β-particles [48, 49].

The dense ionization cascade generated by AEs induces high LET-type radiotoxicity through complex molecular alteration, including lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation. When AEs are emitted near the nuclear DNA, particularly within the cell nucleus, they can cause irreparable DNA DSBs (Figure 2) [50, 51]. Unlike β-emitting radionuclides, radiation types such as AEs and α-emitting radionuclides may be particularly suitable for eradicating single cells or small-volume disease (< 1 cm). The combination of high LET and ultrashort path length allows AE-emitting radionuclides to deliver precise cytotoxic effects with minimal off-target damage—making them mechanistically like α-emitting radionuclides [52, 53]. However, unlike α-emitting radionuclides, AE-emitting radionuclides typically produce either stable or no radioactive daughter products, thereby reducing concerns related to systemic redistribution and non-target toxicity [45, 46]. Notably, [111In]In-, [99mTc]Tc-, [67Ga]Ga-, [125I]-, and [201Tl]Tl- also co-emit γ-photons, enabling their dual use for theranostics by providing both therapeutic AE and γ-emissions suitable for SPECT or γ-scintigraphy, thus offering robust tracking and administered activity verification capabilities in preclinical and clinical settings (Table 1) [54-58].

2.4 Microdosimetric Comparison of β-, α-, and AE-emitting Radionuclides

Despite macroscopic characteristics such as particle energy, LET, and TPR being crucial for comprehending the functionality of emitters, they do not entirely elucidate the varying biological effects observed in TRT. Increasing evidence indicates that the spatial pattern of energy deposition at micrometer- and nanometer-scale dimensions plays an equally critical role in defining therapeutic efficacy and normal tissue toxicity. To align these physical characteristics with biological response and translational impact, a microdosimetric framework is necessary. Therefore, in this section, we review the emitter-specific microdosimetric signatures of β-, α-, and AE-emitting radionuclides and discuss how these nanoscale dose distributions shape their therapeutic windows and vector design considerations [59-61].

β-emitting radionuclides produce low-frequency lineal energy (γ) spectra, with energy distribution below 1 keV/µm, reflecting primarily long-range, sparsely ionizing track structures [62-64]. Stochastic microdosimetry simulations using TOPAS-nBio and Geant4-DNA support that β-particles primarily induce isolated SSBs with a low probability of forming complex DNA damage clusters [65-68]. This extensive and diffuse dose distribution can be advantageous for treating large or diffuse tumors, but its efficacy is limited for treating micro-scale lesions [69]. In contrast, α-emitting radionuclides exhibit a fine dose distribution spectra in the range of 50-200 keV/µm, characterized by high-density linear track structures and minimal lateral scattering [70, 71]. High-resolution measurements using tissue-equivalent proportional counters (TEPC) and nanodosimetric chambers have demonstrated that α-particles generate high-density ionization clusters along their tracks, including complex DSBs that are difficult to repair [72, 73]. At the clinical level, these microdosimetric properties account for the potent cytotoxicity of α-emitting radionuclides against micrometastases and small-volume tumors, while also highlighting the risk of off-target toxicity if targeting vectors are not sufficiently specific [74, 75].

Illustration of Auger electron-emitting radionuclides. Created with BioRender.com.

Key Characteristics of Clinically Relevant vs. Emerging/Experimental AE-emitting Radionuclides. Adapted from [46, 47]

| Radionuclide | Half-life | AEs per decay | Average AEs energy per decay (keV) | Average energy per AEs (keV) | CEs per decay | Average CEs energy per decay (keV) | Average energy per CEs (keV) | γ- or β+ keV (%) | Production method | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical | Copper-64 (64Cu) | 12.7 h | 1.8 | 2.1 | N/P | 5.7E-07 | N/P | N/P | β+, 653(17.9) γ, 1345.8 (0.48) | 64Ni(p, n)64Cu 68Zn(p, αn)64Cu 66Zn(d, α)64Cu |

| Gallium-67 (67Ga) | 3.26 d | 4.9 | 6.3-6.6 | 1.3 | 0.34 | 29.7 | 14.1 | γ, 93 (39) γ, 185 (21) γ, 300 (15) | 68Zn(p,2n)67Ga 67Zn(p,n)67Ga | |

| Technetium-99m (99mTc) | 6.02 h | 4.4 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 15.2 | 13.8 | γ, 140.5 (89) | 99Mo/99mTc 100Mo(p,2n)99mTc | |

| Indium-111 (111In) | 2.80 d | 14.7 | 6.9 | 0.9 | 0.16 | 27.9 | 176.1 | γ, 171.3 (90.7) γ, 245.4 (94.1) | 111Cd(p,n)111In | |

| Iodine-123 (123I) | 13.27 h | 13.7 | 7.2 | 0.5 | 0.16 | 21.0 | 222.6 | γ, 159 (83) | 123Te(p,n)123I 124Xe(n,2n)123I | |

| Iodine-125 (125I) | 59.40 d | 24.9 | 12.2 | 0.5 | 0.94 | 7.3 | 7.7 | γ, 35 (6.7) | 124Xe (n,γ) 125Xe (β+ decay)⇒125I | |

| Terbium-161 (161Tb) | 6.91 d | 10.9 | 8.94 | 0.018-50.9 | 1.4 | 36.7 | 26.2 | γ, 25.7 (23.2) γ, 48.9 (17.0) γ, 74.6 (10.2) | 160Gd(n,γ)161Gd-→161Tb | |

| Thallium-201 (201Tl) | 72.91 h | 20.9 | 14.8 | 0.7 | 0.91 | 29.9 | 32.9 | γ, 167 (10) γ, 135 (3) | 203Tl(p,3n)201Pb | |

| Emerging | Cobalt-58m (58mCo) | 9.04 h | 4.2 | 3.98 | N/P | 1.0 | 18.89 | N/P | γ, 24.9 (0.04) γ, 810.8 (99.4) | 58Ni(n,p)58mCo 58Fe(p,n)58mCo 61Ni(p,α)58mCo |

| Germanium-71 (71Ge) | 11.43 d | 5.2 | 9.2-10.2 | N/P | 0 | 198 | N/P | γ, 174.9 γ, 708.2 | 71Ga[v,β]71Ge 70Ge(n,γ)71Ge | |

| Bromine-77 (77Br) | 2.37 d | 6.6 | 10-15 | 25 | 1.7E-02 | N/P | N/P | γ, 239 (23.1) γ, 297.2 (4.2) γ, 520.7 (22.4) | 77Se(p,n)77Br 75As(4He, 2n)77Br | |

| Palladium-103 (103Pd) | 16.99 d | 13.3 | 8.54 | 0.034-22.3 | 1.8E-05 | 34.97 | 16.6-39.8 | γ, 39.7 (0.07) γ, 357.5 (0.02) | 102Pd(n,γ)103Pd 103gRh(p,n)103Pd | |

| Rhodium-103m (103mRh) | 56.11 m | 5.8 | 2.72 | 0.034-22.3 | 0.99 | 34.97 | 16.6-39.8 | γ,39.7(6.0) | 103Rh(d,d′)103mRh 103Rh(α,α′)103mRh | |

| Cadmium-107 (107Cd) | 6.50 h | 12.4 | N/P | N/P | 0.95 | N/P | N/P | γ, 93.1 (4.7) | 107Ag(d, 2n)107Cd | |

| Tin-117m (117mSn) | 13.80 d | 14.2 | N/P | N/P | 1.15 | N/P | N/P | γ, 158.6 (89) | 116Sn(n,γ)117mSn 114Cd(α,n)117mSn | |

| Antimony-119 (119Sb) | 38.19 h | 23.7 | 8.9 | 0.4 | 0.84 | 17.0 | 20.2 | γ, 24-29 (89) | 119Sn(p,n)119Sb | |

| Tellurium-125m (125mTe) | 57.40 d | 22.4 | N/P | N/P | 1.9 | N/P | N/P | γ, 35.5 (25) | 125Te (n,n′)125mTe | |

| Cerium-134 (134Ce) | 3.16 d | N/P | 7.2 | N/P | N/P | N/P | N/P | β+, 1224 γ, 218 (11.4) γ, 440 (25.9) | 139La(p,6n)134Ce | |

| Lanthanum-135 (135La) | 18.9 h | 12.3 | N/P | N/P | 2.9E-04 | N/P | N/P | γ, 480.5 (1.5) γ, 874.5 (0.16) | 136Ba(p,2n)135La | |

| Terbium-155 (155Tb) | 5.32 d | 13.9 | 4.84 | 38 | 0.77 | N/P | N/P | γ, 86.6 (32.0) γ, 105.3 (25.1) | 155Gd(d,2n)155Tb | |

| Erbium-165 (165Er) | 10.36 h | 7.2 | 5.3 | N/P | 0 | N/P | N/P | 166Er(d,3n)165Tm → 165Er 166Er(p,2n)165Tm → 165Er 165Ho(d,2n)165Er | ||

| Platinum-191 (191Pt) | 2.80 d | 13.3 | 17.8 | 1.3 | 0.99 | 57.1 | 0.2 | γ, 539 (13.7) γ, 409 (8.0) γ, 360 (6.0) γ, 82 (4.9) γ, 172 (3.5) | 190Pt(n, γ)191Pt 191Ir(p, n)191Pt | |

| Platinum-193m (193mPt) | 4.33 d | 27.4 | 10.9 | 0.4 | 2.9 | 126.8 | 42.4 | γ, 135.5 γ, 149.78 | 192Os(α,3n)193mPt | |

| Iridium-193m (193mIr) | 10.53 d | 6.1 | N/P | N/P | 1 | N/P | N/P | γ, 80.2 (0.0045) | 193Ir(n,n'y)193mIr | |

| Platinium-195m (195mPt) | 4.02 d | 36.5 | 23.1 | 0.6 | 2.7 | 161.4 | 58.1 | γ, 65.1 (22.5) γ. 66.8 (39.0) γ, 75.7 (16.8) γ, 98.9 (11.7) | 194Pt(n,γ)195mPt 192Os(α,n)195mPt | |

| Mercury-197m (197mHg) | 23.8 h | 19.4 | 13.5 | 037 | 1.6 | 203.5 | 127.0 | γ, 134 (33.5) γ, 279 (6.1) | 197Au(p,n)197m,gHg |

N/P: Not provided.

Monte Carlo-based Microdosimetric of Therapeutic Radionuclides

| Parameter | β-emitting radionuclides | α-emitting radionuclides | AE-emitting radionuclides |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Monte Carlo simulation tool used | TOPAS-nBio, Geant4-DNA | TOPAS-nBio, MCNP6 | TOPAS-nBio, Geant4-DNA |

| Trach Structure | Long, sparse tracks; low ionization density | Straight, dense, High ionization linear tracks | Extremely short tracks (nm scale), dense localized clusters |

| Linear energy (γ) distribution /LET | < 1 keV/μm | 50-200 keV/μm | Extremely localized clusters (per decay absorbed dose 10-100 kGy, within a few nm) |

| Stochastic variance | High (due to long-range track) | Moderate (predictable Bragg-like) | Extremely high (depending on nuclear/perinuclear localization) |

| Specific energy delivered to nucleus (per decay) | ~10-4-10-3 Gy • cell-1 | 0.1-1 Gy • cell-1 | Up to 10-1000 Gy locally within 2-3 nm DNA |

| Dominant damage type | Mostly SSBs | Dense DSB clusters | Nanometer-scale DSB clusters; based-damage clusters |

| Cluster DNA damage index | Low (1-2 events/μm track) | High (20-40 events/μm track) | Very high (100-500 events localized per decay) |

| Effective range | 0.2-12 mm | 40-80 μm | 2-500 nm |

| Relative biological effectiveness | 1-1.3 | 4-8 | 8-30 (depends on nuclear localization) |

| Cellular dose uniformity | Very uniform | High non-uniform | Ultra non-uniform; decay-site dependent |

| Repair complexity | Low-moderate | High | Highest (multiple DSBs within 10-20 bp) |

| Microdosimetry concerns | Under-killing at nanoscale | Micrometastases, well-targeted lesions | Precision molecular theranostics; nanometer-scale lethality |

AE-emitting radionuclides exhibit fundamentally distinct and highly localized microdosimetric distributions. Following decay, tens to hundreds of low-energy electrons are emitted in rapid cascades, generating extremely high local energy within a few nanometers of the decay site (absorbed doses per-decay are on the order of tens to hundreds of kGy) [76, 77]. These confined ionization clusters induce irreparable DNA DSBs, offering considerable therapeutic potential, which can only be harnessed when controlled to precisely reach DNA beyond intracellular migration [78]. Track-structure modeling at the scale of DNA base pairs indicates that the relative biological effectiveness (RBE) of AE-emitting radionuclides increases rapidly with nuclear or perinuclear localization, exceeding even α-emitting radionuclides on a per-decay basis when decay occurs in the direct vicinity of DNA [79, 80]. Microdosimetric assessment at cellular and subcellular tiers can be performed by computing dose point kernels and S-values using general-purpose electron/photon Monte Carlo software such as PENELOPE/PenEasy [79, 81]. Nevertheless, due to the radiological nature of AE-emitting radionuclides, it is recommended to utilize specific nanodosimetry measurement codes such as Geant4-DNA or TOPAS-nBio for a comprehensive understanding of the tracheostomy structure, cluster formation, and chemical effects at the DNA level.

Microdosimetry offers criteria for the selection of radionuclides appropriate for clinical translation. As next-generation AE-emitting RLTs and potential mitigation strategies advance through the translation pipeline, the incorporation of microdosimetry parameters in preclinical evaluation and treatment planning is increasingly highlighted. The table below summarizes and compares Monte Carlo-based microdosimetry information for therapeutic radionuclides, including α-, β-, and AE-emitting radionuclides (Table 2).

3. Emerging Auger Electron-emitting Radionuclides: Current Limitations and Potential Mitigation Approaches

3.1 Key Challenges and Limitations

AE-emitting radionuclides offer unique opportunities for precision cancer therapy due to their highly localized and potent radiobiological effects. The therapeutic potential of radionuclides emitting AE can theoretically be determined by the average number of AEs emitted per nuclear decay. Radionuclides with higher AEs emissions can also enhance their therapeutic effects with lower doses due to the lower number of decays requiring irreversible DNA damage. Therefore, AE-emitting radionuclides ([195mPt]Pt-(36.5 AE/decay), [193mPt]Pt-(27.4), [119Sb]Sb-(23.7), [125I]-(23.0), and [201Tl]Tl-(20.9)) are generally preferred in TRT. Conversely, commonly used isotopes such as [123I] (13.7), [161Tb]Tb- (10.9), [111In]In- (7.4), [67Ga]Ga- (4.9), [99mTc]Tc- (4.4), and [64Cu]Cu- (1.8) have significantly lower incidence of side effects, which may require increasing the activity of radioactivity administered or extending the residual time in the body to achieve similar cytotoxic effects [47]. Nevertheless, this may be the basis for prioritizing radionuclides that produce high-yield AE, which presupposes that the AE-emitting radionuclides penetrate sufficiently into intracellular DNA and their effectiveness is verified. This is because if radionuclides are confined to cytoplasm or cell surface, their therapeutic effects may be limited. Additionally, it can be argued that enough care should be given to whether factors like half-life may enhance therapeutic efficacy and whether the development and supply of high-yield AE-emitting radionuclides can fulfill demand.

Although AE-emitting radionuclides can deliver highly localized and potent cytotoxic effects, truly AE-pure isotopes are rare, as most also emit high-energy β-particles or conversion electrons (CEs) alongside diagnostic X- and γ-rays. These unintended emissions can reduce the primary therapeutic advantage of AE radionuclides, which is precise targeting with minimal collateral damage. Consequently, the photon-to-electron (p/e) energy yield ratio has become an important ancillary criterion in the clinical evaluation of AE-emitting RLTs [82]. Among the most promising AE-emitting radionuclides are the platinum-based isotopes [195mPt]Pt- and [193mPt]Pt-, which display remarkably high AE yields per decay and emit low-energy γ-photons (98.9 and 66.8 keV, respectively), leading to low p/e energy ratios of 0.42 and 0.09 [82]. Although moderate γ-emission might permit valuable imaging and dosimetry applications, excessive γ-radiation as observed with isotopes such as [125I]-, [123I]-, [161Tb]Tb-, [111In]In-, [67Ga]Ga-, [99mTc]Tc-, and [64Cu]Cu- may lead to unintended toxicity at therapeutic levels [83]. Furthermore, because AE radiation has an inherently limited TPR and lacks a crossfire-effect, treating tumors with heterogeneous uptake patterns often requires high administered activities or repeated dosing, which can inevitably result in accompanying γ-photon emission. This p/e energy ratio is a factor that should be carefully considered in the clinical translation process of AE-emitting RLT optimization to ensure both efficacy and safety for patients and operators.

Effective application of AE-emitting radionuclides requires careful consideration not only of their radiophysical properties but also of limitations in chemical compatibility, nuclear reaction feasibility, and global availability. More than 65% of AE-emitting radionuclides identified to date are either unavailable or subject to severe supply restrictions, and their large-scale synthesis requires rare high-flux neutron reactors or high-energy α-particle cyclotrons, which are not widely accessible. An indirect technique for producing [195mPt]Pt- via a double-neutron capture process on [193Ir]Ir- has been attempted; however, it suffers from low yields and challenges in purifying the chemically resistant [193Ir]Ir target material. Furthermore, isotopic contaminants such as [192/194Pt]Pt- can be produced during irradiation alongside [195mPt]Pt-, necessitating complex chemical separation and purification strategies [84]. High-purity [193mPt]Pt- is often produced by the 192Os(α,3n) reactions or alternative high-energy irradiation techniques, which necessitate costly osmium targets and specialized accelerator equipment [85]. Additionally, AE-emitting actinides such as [231Th]Th-, [237U]-, and [239Np]Np- exhibit excellent AE yields, but their clinical use is constrained by regulatory restrictions on nuclear material handling, complex decay chains, and difficulties in achieving acceptable purity levels. Despite their potent theranostic profile, as detailed in the following section, the clinical translation of AE-emitting RLTs using [161Tb]Tb- is fundamentally limited by constraints in its specialized supply chain and manufacturing scalability. No-carrier-added, high-specific-activity [161Tb]Tb- is primarily produced by neutron irradiation of highly enriched [160Gd]Gd- targets via the 160Gd(n,γ)161Gd → 161Tb reaction, representing the current standard for clinical-grade radionuclide production [86]. However, significant hurdles are the limited availability of highly enriched [160Gd]Gd- target material and the rigorous, time-intensive radiochemical separation process necessary to obtain high-purity [161Tb]Tb- from neighboring lanthanide contaminants [87, 88]. Isolating [161Tb]Tb- from the 161Dy generated concurrently with the predominant Gd target material is a challenging endeavor due to the closely analogous chemical characteristics of these lanthanide elements, necessitating meticulously refined techniques to attain high purity [89]. Recent advances, including novel resin-based chromatographic techniques (e.g., P350@resin) [90], electrochemical oxidation [89], and integration into automated synthesis modules [91, 92], have enabled baseline-level separation within a few hours, supporting rapid and reproducible production suitable for clinical applications.

To develop targeted AE-emitting RLT, researchers should create stable radiometal complexes that exhibit compatibility with biological systems. The majority of AE-emitting radionuclides are metallic ions; therefore, effective bifunctional chelators are essential to ensure their strong adherence to the targeted vector and optimal functionality [93]. Although thermodynamic stability, typically quantified by formation constants (KML = [ML]/[M][L]), indicates the strength of the binding between two molecules. However, kinetic stability under normal conditions is what usually determines whether a drug is safe to use in the clinic [94]. Biological environments comprise several competing elements, such as endogenous metals, natural chelators, and reducing agents, which may compromise the stability of metal complexes. Extensive research has been conducted on chelators such as 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (DOTA), diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA), 1,4,7-triazacyclononane-1,4,7-triacetic acid (NOTA), and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) for lanthanides that emit AE; however, further investigation is required to explore lesser-studied isotopes and their coordination properties [94]. The reversible oxidation-reduction dynamics between Sb(III) and Sb(V) of [119Sb]Sb, along with its intricate coordination chemistry involving oxygen, sulfur, and nitrogen donors, complicate the development of a stable and long-lasting chelator for use in the body [95]. DOTA and NOTA, prevalent macrocyclic ligands, lack sufficient stability in vivo. This prompts concerns regarding chelate dissociation, off-target effects, and the reduced effective dosage at the tumor location [96, 97]. Recent studies on chelator chemistry using Sb(V)-based coordination techniques show promise; however, these developments remain in the preclinical phase, and clinical implementation has not yet occurred [98, 99]. The effective production of AE-emitting RPs hinges on the selection of an appropriate chelator. This involves investigating factors like stability, mobility, and efficacy in cancer targeting.

AE-emitting radionuclides exhibit exceptionally high cytotoxicity when decays occur near DNA, a strategy that has historically produced potent DNA DSBs and strong cell kill compared with cytoplasmic localization. However, this advantage can have drawbacks, as non-specific binding or intercalation of AE-emitting constructs into DNA of non-tumor proliferating cells may result in off-target DNA damage, thereby narrowing the therapeutic window [100]. Indeed, radioconjugates containing DNA-intercalating moieties (e.g., an acridine-orange group linked to a radionuclide) have demonstrated that the RBE of AEs strongly depends on proximity to DNA; when the radionuclide is not sufficiently close to the double helix, the yield of DSBs and cytotoxic effects decreases dramatically [101]. Furthermore, recent high-resolution, simulation-based nanoscale dosimetry studies indicate that energy deposition and DNA break yields from [125I] decay are highly sensitive to the precise positioning of AE-emitting radionuclides relative to individual base pairs [59, 102]. This implies that even minor deviations in subcellular or local geometry, such as imperfect nuclear import or non-uniform chromatin structure, can shift AE decays outside the critical nanometer range, thereby reducing efficacy or, conversely, causing unpredictable off-target genotoxicity. Thus, it may be inferred that dosimetry models at both macroscopic and cellular levels in AE-emitting RLTs are inadequate for consistently ensuring safety or predicting treatment outcomes [59].

AE-emitting radionuclides can directly induce DNA DSBs through concentrated interactions or indirectly cause DNA damage through the generation of ROS. If this damage is not repaired, it can lead to cell death. However, misrepair can result in chromosomal abnormalities, micronuclei formation, and other characteristics of genomic instability. For example, a study using [123I]IUdR in human lymphocytes reported a dose-dependent increase in micronuclei formation even at low doses (~0.15 Gy) using the cytokinesis-block micronucleus assay, and the RBE values were relatively high, ranging from 3 to a maximum of 10 compared to γ-radiation [103]. While many preclinical studies report chromosomal abnormalities or cytotoxicity, the relationship between acute AE-induced DNA damage and the risk of transformation, including long-term genomic instability or persistent rearrangements and secondary malignancy development, is not well understood. Furthermore, heterogeneity in uptake, nuclear entry, chromatin binding, and cellular repair capabilities among different cell types (tumor cells vs. normal cells) leads to unpredictable chromosomal instability. It should also be considered that if AEs accumulate in the perinuclear region instead of directly binding to DNA, their accumulation could reduce efficacy and induce chromosomal instability in normal tissues.

The key limitations of AE-emitting radionuclides as successful RPs, along with their mechanistic/technical basis, impact on clinical translation, and potential mitigation strategies, are summarized in the table below (Table 3).

3.2 Potential Mitigation Strategies

3.2.1 PARP

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) is an important biomarker that is found in many different types of tumors. In cancer cells, the DNA SSB repair process involves PARP enzymes, which help change the structure of chromatin and bring in DNA repair factors that allow the stalled replication forks [104]. Inhibiting PARP prevents the repair of DNA DSBs, leading to the accumulation of unresolved lesions that ultimately result in cell death. Utilizing this concept, PARP inhibitors have evolved into pharmaceuticals that have the potential to treat several different types of cancer, both on their own and with other treatments [105]. Given that PARP1 functions near the nucleus, conjugating AE-emitting radionuclides to PARP-targeted ligands has the potential to deliver electron cascades within just a few nanometers of DNA, thereby maximizing therapeutic efficacy by depositing energy directly in nuclear and perinuclear regions. This data indicates that PARP1-targeted AE-emitting RLT may provide an effective approach to address the significant drawbacks of traditional delivery vehicles (e.g., antibodies or peptides), which frequently persist in the cell membrane or cytoplasm, leading to diminished nuclear delivery efficiency and increased targeting variability. Preclinical studies across five major tumor types, including glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) [106], triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) [107], prostate cancer [108], ovarian cancer [109], and pancreatic cancer [110], strongly support the clinical applicability of PARP-targeted AE-emitting RLT. These results suggest that increased PARP1 expression, genomic instability, or defects in DNA repair processes represent a powerful molecular target for the application of AE-emitting RLT strategies that need to reach the DNA in various tumor types. Despite its broad applicability, the intrinsically short path length of AEs requires precise intranuclear delivery, which may be inconsistent in heterogeneous tumors or in those with limited PARP accessibility. The lipophilicity of the RPs, efflux mechanisms, suboptimal pharmacokinetics (PK), and variability in DNA-binding efficiency further limit dose deposition at the chromatin level. Currently, most of the available data remains in the preclinical stage, limiting clinical validation, and there may be considerable uncertainty regarding toxicity to normal tissues, particularly in proliferative tissues with endogenous PARP expression. Further optimization of biomarker-based patient selection is needed for application of AE-emitting RLTs targeting PARP [111].

3.2.2 Nanoparticles

Nanoparticles (NPs) are widely applied as carriers for TRT, representing a promising strategy to overcome major challenges hindering clinical application by amplifying radioisotope payload, facilitating targeting and cellular uptake, improving PK, and enabling multifunctional design (e.g., combination with sensitizers). In particular, the integration of organic and inorganic nanostructures ultimately provides a versatile platform for amplifying DNA damage induced by AE-emitting radionuclides. A detailed overview of these nanoparticle-based strategies is presented in the table below, highlighting the mechanisms and advantages of each NP's application in AE-emitting RLTs, its unique limitations and challenges, and representative research examples (Table 4) [112].

Key Limitations of AE-emitting Radionuclides as Successful RPs: Mechanistic/Technical Basis, Impact on Clinical Translation, and Mitigation Strategies

| Limitations | Mechanistic / technical basis | Impact on clinical translation | Potential mitigation strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extreme short range → strong subcellular location dependence | AEs have nm range; lethal effect requires decay at or extremely close to DNA/nucleus | If the radionuclide fails to reach DNA/nucleus, the therapeutic effect is negligible → narrow therapeutic window; high variability between target/cells | Design vectors that intentionally localize to the nucleus (DNA intercalators, nuclear-targeting peptides/proteins, and PARP-targeted agents); validate subcellular distribution quantitatively |

| Difficulty of achieving reproducible, high fraction of DNA/nucleus uptake | Many targeting vectors (antibodies, peptides) accumulate on the membrane or in the cytosol; only a small fraction reaches nucleus | Low and variable nuclear delivery → inconsistent efficacy across patients/tumor types; hard to power clinical trials | Use small molecules that bind DNA or DNA-associated proteins (PARP inhibitors, nucleoside analogues); engineer endosomal escape and NLS; patient selection by biomarker |

| Lack of cross-fire for bulky disease | AEs deposit energy over very short distances; they produce little to no cross-fire dose compared with β/α-emitting radionuclides | Ineffective against bulky tumors; narrows clinical indications to microscopic residual disease or disseminated single cells | Target indications where micrometastases or minimal residual disease predominate (adjuvant setting, leptomeningeal disease); combine with agents that debulk tumors |

| Potential for heterogeneous normal tissue microdosimetry & unexpected toxicity | Small-scale hotspots (microdosimetry) can cause high local doses in normal cells if mis-localized (e.g., kidney, bone marrow microenvironments) | Unanticipated toxicities could appear despite acceptable average organ doses, complicating safety monitoring | Implement microdosimetry risk assessment, a sensitive biomarker of DNA damage in normal tissues, and conservative first-in-human dosing |

| Radionuclide physical half-life trade-offs | Long half-life isotopes (e.g., [125I]) increase non-target exposure; short half-life isotopes (e.g., [64Cu]Cu-, [99mTc]Tc-, [123I]) require rapid delivery/complex logistics | Logistical factors (production, shipping, and timing) and concerns about non-target doses restrict the range of isotopes feasible for clinical use | Choose an isotope with a half-life matched to the vector PK; optimize the production/supply chain; Use preclinical PK modeling to guide isotope choice |

| Radiochemistry / In vivo stability | Some isotopes have weak chelation chemistry; Radioiodination undergoes in vivo dehalogenation | Off-target dose to sensitive organs complicates the safety profile and may limit dosing | Use chelators optimized for AE radionuclides, stabilized metal complexes, metabolism-stabilized linkages, prosthetic groups, or non-iodine AE-emitting radionuclides |

| Production, supply & radio-pharmacy constraints | Some AE-emitting radionuclides have limited production routes or require on-site cyclotron/complex radiochemistry | Scale-up to multi-center trials and routine clinical use are hindered by supply chain and cost issues | Prioritize clinically scalable isotopes; develop centralized radiopharmacies or generator/cyclotron networks, and ensure regulatory harmonization |

| Regulatory, trial design & commercialization hurdles | Need for novel microscale dosimetry endpoints, complex manufacturing, and narrow indication complicate approvals and commercial investment | Slow or absent commercial development; difficulty in obtaining funding and executing large trials | Early engagement with regulators; designed phased, biomarker-driven trials; public-private partnership to derisk development |

| Competition from clinically successful β/α RLTs & limited commercial incentives | β- and α-emitting radionuclides have shown robust clinical success and broader applicability (cross-fire + established dosimetry) | Funding and industry attention tend to favor non-AE approaches, resulting in slower progress for AE methods. | Highlight distinct advantages in niche applications (e.g., high therapeutic index for micrometastases); explore combinations of treatment regimens and seek translational partnerships. |

AE: Auger electron; PARP: Poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase; NLS: Nuclear localization sequence; PK: Pharmacokinetics

Nanoparticle-based Radionuclide Carriers for Overcoming the Intrinsic Limitations of AE-emitting RLTs. Adapted from [112].

| Category | Types | Radiolabeled strategy | Mechanism / Advantages | Limitations / Challenges | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic | MCPs | [111In]In- via DTPA chelators on polymer backbone | High specific activity (29 chelators per polymer); amplified radionuclide loading; antibody (e.g., trastuzumab) conjugation for targeting; potential nuclear localization via NLS peptides | Rapid clearance; steric hindrance to receptor binding; polyanionic charge causing non-specific uptake (liver); immunoreactivity; low fraction internalized / slow nuclear transport | [113-118] |

| BCMs | [111In]In-DTPA attached to hydrophilic corona | Co-delivery design in which the hydrophobic core carries a radiosensitizer (e.g., methotrexate), surface carries targeting (e.g., trastuzumab Fab) and NLS peptides; enables simultaneous delivery of AE-emitting radionuclide and sensitizer to nucleus; enhances cytotoxicity via synergy | Complex synthesis; potential heterogeneity in micelle formation; limited tumor penetration; PK variability; non-uniform cellular/subcellular distribution; scale-up challenges | [119, 120] | |

| Stimuli responsive micelles (PEG-based) | [125I] (e.g., on PEG-phenolic compound) | Controlled release occurs in response to stimulus (e.g., laser, pH) to trigger release of [125I] near/inside the nucleus; PEG improves circulation time; allows image-guided or light-triggered AE-emitting RLTs | Requires external stimulus (e.g., laser) for activation; tissue penetration of stimulus; complexity of formulation; potential off-target release; stability of radiolabel and formulation in vivo | [121, 122] | |

| MORF / Streptavidin-based NP | [111In]In- via DOTA or NHS-MAG₃ chelators, or [125I] labeling on MORF backbone | Modular assembly: streptavidin-biotin enables combination of MORF (oligomer), antibody, NLS, or TAT-peptide; MORF binds RNA / DNA → increases nuclear proximity; high loading; flexible design | Non-specific uptake (liver, kidneys, spleen) in vivo; limited internalization/nuclear delivery; immunogenicity (streptavidin); label stability (especially [125I], risk of dehalogenation); premature release by weak non-covalent binding | [123-126] | |

| Chitosan-based NPs | [125I]-labeled antisense oligonucleotide (e.g., antisense AFP) encapsulated in chitosan NP | Gene-targeted therapy: delivery of antisense oligos to reduce target gene expression; positive charge of chitosan enhances cellular uptake; chitosan protects the oligo and brings [125I] near DNA / target mRNA; increased DNA damage compared to free oligo | Low in vivo delivery efficiency; stability of radiolabeled oligo; cell-type specificity concerns; potential toxicity of chitosan NPs; not fully addressed with clearance and biodistribution | [127] | |

| Dendrimers (e.g., PAMAM) | [111In]In- via many DTPA or DOTA chelators on peripheral amines | Very high payload (many chelators per dendrimer); well-defined, monodisperse structure; multivalency allows for attachment of targeting ligands and possibly drugs; cationic surface promotes cell uptake via electrostatics; high internalization (~77.6% in SHIN-3 cells after 24 h in one study) | Biodistribution issues: long-term accumulation (liver, kidney) for higher-generation dendrimers; potential toxicity due to cationic surface; radiolabel stability; slow clearance; synthetic complexity; GMP translation challenges | [128-131] | |

| Liposomes | [125I]-daunorubicin derivative encapsulated; or [111In]In-labeled peptide (e.g., hEGF) loaded and chelated | High loading capacity; PEGylation improves circulation; surface functionalization (antibody, ligand) for targeting; two-step strategies: e.g., internalization, then release, then nuclear delivery; controlled release (e.g., ultrasound-triggered cavitation) | Penetration in solid tumors is limited; RES clearance; possible leakage of cargo; triggered release (e.g., ultrasound) may not be efficient in vivo; radiolabel release, in vivo stability; lack of comprehensive in vivo toxicity/efficacy data | [132-134] | |

| Inorganic | Gold NPs (AuNPs) | [125I] directly bound to the gold surface; or [111In]In- via chelator (DTPA / DOTA) on surface-modified AuNPs | High surface area allows multivalent ligand attachment for targeting; PEGylation for stability; perinuclear accumulation observed; high-Z potential for secondary electron production (photo, AE) when combined with external radiation; dual-modality theranostics possible | RES uptake and rapid clearance; limited tumor accumulation after IV Injection; steric hindrance reduces targeting affinity; long-term retention, potential toxicity; surface modification complexity; in vivo translation challenges; low IV tumor uptake (1.2% IA/g in one study); intratumoral injection needed for high uptake | [135-139] |

| Platinum NPs / Core-shell Platinum structures | [193mPt]Pt, [195mPt]Pt (intrinsic radionuclide) | Enhanced high-Z platinum via conversion electrons; core-shell design allows control of surface chemistry and stability; potential to combine with chemotherapy (Pt-based) | Limited data in the context of AE-emitting RLTs; complex synthesis; radiolabel stability; toxicity concerns; unknown biodistribution/clearance; scale-up and regulatory hurdles | [140] | |

| Titanium dioxide (TiO₂) NPs | [125I] attached to surface (halogen) | High surface reactivity; inherent stability; potential for radical generation (e.g., •OH) after decay/activation; high-Z enhancement of local radiation dose; surface functionalization possible | Limited in vivo data; radiolabel instability (I-dehalogenation risk); long-term biocompatibility / toxicity unclear; clearance and biodegradation not well established; possible oxidative damage to non-target tissues | [141] | |

| Inorganic / Coordination Polymer (High-Z) | High-Z core (Hf) porphyrin coordination polymer NPs | Using Hf and porphyrin ligand; potential for radionuclide attachment | Hf allows dose amplification by external radiation (photoelectron cascade); porphyrin offers multifunctionality (imaging, targeting, possible photosensitizer); a biodegradable coordination structure; potential for tumor accumulation via EPR | Limited specific examples in the context of AE-emitting radionuclides; synthesis complexity; radiolabel stability; immunogenicity; unknown PK; lack of in vivo therapy data; scale-up to clinical grade challenging | [142] |

MCP: Metal-chelating polymer; DTPA: Diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid; NLS: Nuclear localization sequence; BCM: Block copolymer micelle; PEG: Polyethylene glycol; MORF: morpholino oligomer; NP: Nanoparticle; DOTA: 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid; NHS-MAG3: 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid; TAT: Trans-activating transcriptional activator; AFP: Alpha-fetoprotein; PAMAM: poly(amidoamine); GMP: Good manufacturing practices; hEGF: Human epithelial growth factor; RES: Reticuloendothelial system; IV: Intravenous; % IA/g: Percentage of injected activity per grams EPR: Enhanced permeability and retention

From a theranostic perspective, nanostructures in AE-emitting RLT offer several advantages: (i) enhanced radionuclide payload for improved multimodal tumor imaging contrast and therapeutic efficacy, (ii) improved programmable PK properties extending intratumoral retention time, (iii) targeted modularity enabling ligand exchange and multivalent binding on the nanoparticle surface, and (iv) control over mechanism-based intracellular trafficking pathways, including nuclear translocation or lysosomal escape, which are crucial for radionuclide efficacy. Furthermore, high-Z NP materials can go beyond acting as sensitizers to external beam radiation, inducing photoelectron emission at the nanoparticle surface to amplify local energy deposition or enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect in tumors, providing advantages consistent with theranostic optimization. NP-based radionuclide-emitting RLT has the potential to become a next-generation RLT platform for optimizing theranostic strategies through ongoing multidisciplinary research and development aimed at increasing the possibility of clinical translation.

3.2.3 Click Chemistry and Biorthogonal Radioconjugation

The short range from AE-emitting radionuclides makes their cytotoxicity critically dependent on the proximity of the radionuclide to the DNA, motivating research toward agents capable of efficient nuclear localization. The development of these sophisticated RPs is strongly supported by click chemistry radiolabeling, which allows the rapid, high-yielding, and modular synthesis of complex bioconjugates under mild conditions, essential for handling short-lived radionuclides [143]. Current research is focused on optimizing two main bioorthogonal approaches. The first, direct radiolabeling, employs reactions such as strain-promoted azide-alkyne cycloaddition (SPAAC) or inverse electron-demand Diels-Alder (IEDDA) to attach AE-emitting radionuclides to targeting vectors (e.g., peptides, antibodies) with high selectivity [144]. The second, and more strategically significant, approach is pretargeting, in which an unlabeled targeting molecule is first allowed to accumulate at the tumor site, followed by administration of a smaller, radiolabeled “click” partner [145]. This sequential delivery markedly enhances the tumor-to-background ratio (TBR) while minimizing systemic toxicity by rapidly clearing unbound radiolabeled small molecules [146]. These efficient radiolabeling techniques are employed to produce a broader spectrum of radiotracers, including positron emission tomography (PET) or SPECT agents, and complement conventional AE-emitting radionuclides, hence enhancing the theranostic arsenal [147]. It is essential to continue developing more rapid click chemistry and bioorthogonal conjugation reactions that exhibit enhanced efficacy in vivo to optimize the therapeutic window and reinforce the synergy between AE-emitting RLTs and click- and bioorthogonal conjugation chemistry in personalized nuclear medicine.

3.2.4 Protein Engineering Strategies

The fundamental limitation of AE-emitting RLTs is the required proximity of the radioisotope to the nucleus or DNA, which necessitates strategies beyond simple extracellular binding. While nuclear localization sequence (NLS) engineering has long been used to promote intranuclear shuttling, current protein engineering efforts are focused on overcoming systemic barriers such as poor PK and off-target toxicity [148]. A major trend is the transition from bulky monoclonal antibodies to high-affinity, rapidly clearing scaffolds such as nanobodies (variable domain of heavy chain-only antibody, VHHs) and affibodies [149]. These smaller formats offer superior tumor penetration and achieve high TBR at earlier time points, a feature that is particularly critical for AE-emitting radionuclides [150]. Another significant strategy involves the engineering of PK extenders to optimize in vivo circulation time [151]. This goal is typically achieved by fusing the targeting scaffold to human serum albumin or by incorporating specific albumin-binding domains (ABDs) to enable temporary “hitchhiking” [152]. The incorporation of albumin can enhance the EPR effect, resulting in a significant increase in tumor accumulation and a substantial reduction in renal excretion [153]. A protein engineering strategy that integrated an ABD with a HER2-targeted nanobody enhanced the systemic half-life of [125I], facilitating uniform distribution of the drug throughout the body, which is essential for substantial remission following a single dose in preclinical models [154]. A contemporary strategy in tumor RLT involves the integration of the tumor microenvironment (TME) with protein engineering [153]. Cathepsin B-sensitive GFLG or MMP-sensitive PLGLWA linkers, widely employed for spatially regulated drug release via tumor- or lysosome-specific protein therapy activation, may be suggested [155, 156]. Incorporating these linkers prior to NLS ensures the protein carrier remains stable and concealed during its transit through the body. When cleaved in the TME, the NLS is exposed, facilitating the protein's entry into the nucleus. A protein engineering-based strategy, combined with and integrated by conventional NLS in AE-emitting RLT, provides an effective approach to improve intracellular delivery and increase accessibility to DNA molecules, resulting in a synergistic effect [148].

4. Historical Use and Prior Development (Success/Failure) of AE-emitting RLTs

Therapeutic applications of AE-emitting radionuclides have received increasing attention in the field of theranostics, alongside α-emitting radionuclides. Despite growing interest and promising outcomes from numerous preclinical and early-phase clinical investigations, no AE-emitting RP has yet been approved by the U.S. FDA. This section of the review summarizes the historical utilization and developmental efforts, both successful and unsuccessful, of AE-emitting RLTs (Table 5).

Historical Use and Prior Development on AE-emitting RLTs

| Radionuclide | Agent | Target | Tumor (or model) | Primary findings | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [125/123I] | [125I]IUdR | Thymidine of DNA | Hamster Chinese Lung Fibroblast (V79) | The potent high-LET cytotoxicity of [125I]IUdR was demonstrated by its ability to induce significantly more DNA DSBs and cell death at only 0.0037 Bq per cell. | [157] |

| Rat Leptomeningeal metastases (9L) | The use of [125I]IUdR effectively prolonged the time to paralysis and showed selective retention in tumor and thyroid tissues, which indicates targeted antitumor activity. | [158] | |||

| Patient with liver metastases from colorectal cancer | Given the sustained uptake of [125I]IUdR in liver tumors and the limited fraction of S-phase cells at any given time (15-50%), repeated intra-arterial injections are necessary to achieve effective tumor cell inactivation. | [159] | |||

| [123I]IUdR | Murine ovarian tumor (MOT) cells originated spontaneously in C3H female mice | Selective uptake of [123I]IUdR in tumor-bearing models with 1% of injected administered activity associated with MOT cells 24 h post-injection significantly prolonged survival, increasing median survival by 11 d and achieving 20% absolute survival at the highest administered activity. | [160] | ||

| Patient with liver metastases from colorectal cancer | Biochemical modulation with 5-FU and folinic acid increased early tumor uptake of [123I]IUdR from 9.1% to 14.9% IA, representing a 72% enhancement that remained stable up to 42 h post-infusion. | [161] | |||

| [125I]DCIBzL | PSMA | Human prostate cancer cell line with PSMA-positive (PC3-PIP) | [125I]DCIBzL selectively induced DNA damage and suppressed clonogenic survival in PC3-PIP cells, leading to significantly delayed tumor growth in vivo compared with PC3-Flu controls. | [162] | |

| Micrometastatic prostate cancer cell line derived from metastatic lumbar vertebrae (PC3-ML) | Treatment of [125I]DCIBzL at therapeutic administered activity (≥ 18.5 MBq) delayed metastasis, improved median survival, and exhibited minimal toxicity, with dosimetric modeling supporting a favorable therapeutic window due to low renal nuclear administered activity relative to tumor cell nuclei. | [163] | |||

| [125I]CLR1404 | APC | Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC, MDA-MB-231) | [125I]CLR1404 demonstrated favorable tumor-to-bone marrow dosimetry and was well tolerated at a therapeutically administered activity (74 MBq), producing approximately a 60% reduction in TNBC tumor volume, delaying metastatic progression, and significantly extending survival in TNBC models. | [164] | |

| [125I]35A7 | CEA | Peritoneal carcinomatosis (A431) | Targeting CEA with non-internalizing [125I]35A7 resulted in enhanced tumor control and survival compared with [125I]m225, owing to greater tumor retention and reduced catabolite loss, demonstrating that efficient AE-emitting RLTs can be achieved without the need for nuclear targeting. | [165] | |

| Peritoneal carcinomatosis (A431) | The promising therapeutic index of short-course intraperitoneal [125I]35A7, characterized by high tumor targeting and low off-target toxicity, supports its integration with radiation-enhancing drugs in the post-surgical management of small-volume peritoneal disease. | [166] | |||

| Human colorectal cancer (p53+/+/or p53-/-HCT-116) | The accumulation of DNA DSBs and the resulting micronuclei formation following exposure to [125I]35A7, regardless of internalization, indicates that hypersensitivity arises from defective DNA repair mechanisms at low administered activity rates. | [167] | |||

| [125I]CO17-1A | EpCAM | Human colon carcinoma (GW-39) | [125I]CO17-1A exhibits superior tumor suppression compared to [131I]CO17-1A despite similar toxicity profiles, suggesting that therapeutic efficacy may be influenced more by radionuclide characteristics than by antibody internalization. | [168] | |

| [125I]mAb-425 | EGFR | Patient with GBM and AAF | In a Phase I/II trial with 180 patients who had high-grade gliomas, adding [125I]mAb-425 to their treatment significantly increased their chances of living longer, especially for patients under 40 with high Karnofsky scores. This supports its possible use in treating GBM and AAF. | [21, 169, 170] | |

| [111In]In- | [111In]In-CO17-1A | EpCAM | Human colon carcinoma (GW-39) | [111In]In-CO17-1A provided greater therapeutic efficacy than its [90Y] counterparts at matched toxicity levels, indicating the possible use of AE-emitting radionuclides in targeted radioimmunotherapy. | [168] |

| [111In]In-DTPA0-Octreotide | SSTR-2 | Patient with malignant NET | [111In]In-DTPA0-octreotide treatment in patients with advanced NETs showed minimal toxicity and induced disease stabilization or tumor shrinkage in a substantial subset, particularly among those with higher tumor radioligand accumulation. | [171] | |

| Various carcinomas with SSTR-2 positivity | While [111In]In-DTPA0-octreotide provided clinical benefit with preserved renal function due to the limited range of AEs, cumulative administered activities above 100 GBq posed a risk of hematologic complications, such as myelodysplastic syndrome. | [18] | |||

| Neuroendocrine liver metastases | Although intra-arterial administration of [111In]In-DTPA0-octreotide in patients with hepatic NETs showed favorable tumor responses and a median overall survival of 32 months, subsequent studies revealed limited long-term efficacy and raised safety concerns due to γ-emission. | [20] | |||

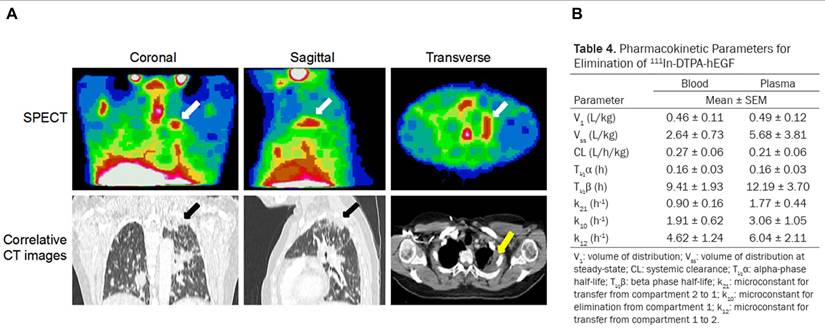

| [111In]In-DTPA-hEGF | EGFR | Human breast cancer cell with EGFR positive (MDA-MB-468) | With high nuclear uptake and up to 25 Gy delivered per cell, [111In]In-DTPA-hEGF effectively reduced the viability of MDA-MB-468 cells and showed no hepatotoxicity or nephrotoxicity in vivo, highlighting its promise as a targeted therapy for hormone-resistant breast cancer. | [172] | |

| [111In]In-DTPA-hEGF induced tumor regression in MDA-MB-468 xenografts (slopes: 0.009 and 0.0297 d-1, P < 0.001) and delivered up to 1400 cGy to the cell nucleus, supporting its use for micrometastatic breast cancer. | [173] | ||||

| [111In]In-DTPA-hEGF induced nuclear translocation (131 ± 6 MBq/nucleus) and significant DNA damage (35 ± 15 γ-H2AX foci) in MDA-MB-468 cells, resulting in a surviving fraction of 0.013 ± 0.001, which correlated with EGFR expression. | [174] | ||||

| Patients with metastatic breast cancer (EGFR-positive) | [111In]In-DTPA-hEGF demonstrated a favorable safety profile in a Phase I trial, with no administered activity-limiting toxicities up to 2290 MBq, rapid blood clearance, low administered activity to normal organs, and visible tumor accumulation in 47% of patients, although no objective tumor responses were observed. | [22] | |||

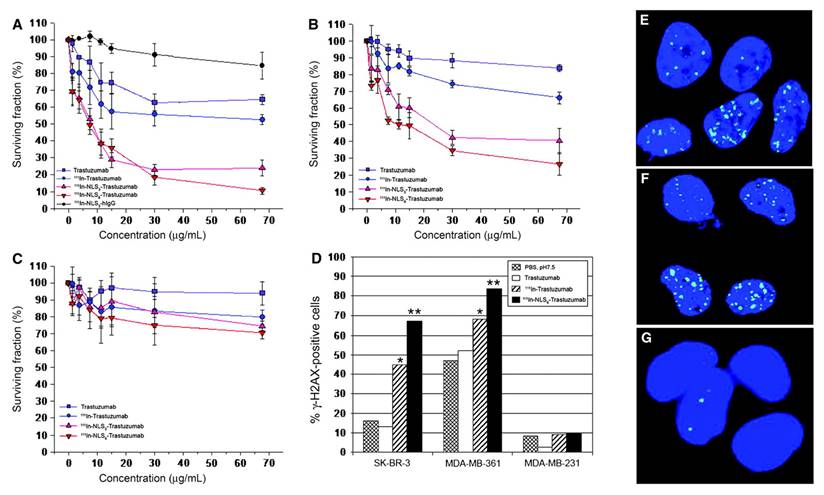

| [111In]In-DTPA-NLS-Trastuzumab | HER2 | Human breast cancer cell lines with HER2 positive (SK-BR-3, MDA-MB-361) | Conjugation of [111In]In-DTPA-Trastuzumab with 6 NLS peptides enhanced nuclear localization in HER2-positive breast cancer cells (e.g., internalization in SK-BR-3 increased from 7.2% to 14.4%, and nuclear uptake in xenografts from 1.1% to 2.4-2.9%), resulting in up to a 6-fold increase in cytotoxicity compared with unlabeled trastuzumab and a 5-fold increase compared with [111In]In-DTPA-Trastuzumab. | [115] | |

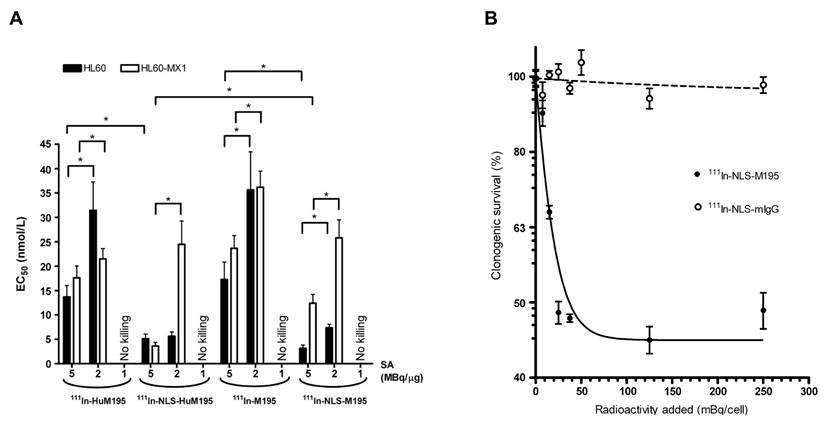

| [111In]In-NLS-HuM195 | CD33 | Human leukemia cell line (HL-60) | [111In]In-NLS-HuM195 achieved potent AML cell killing by increasing nuclear uptake up to 66% and reducing IC50 and IC90 values by over 50% compared to non-NLS controls, eliminating HL-60 colonies at 3.33 MBq/cell and showing no adverse effects in vivo, highlighting its therapeutic potential. | [175] | |

| Mitoxantrone-resistant HL-60 cell line (HL-60-MX-1) | [111In]In-NLS-Trastuzumab significantly enhanced nuclear uptake and cytotoxicity against HL-60-MX-1 cells, with patient-derived AML specimens also showing variable but positive responses, suggesting efficacy against MDR phenotypes, including Pgp-170, BCRP1, and MRP1. | [176] | |||

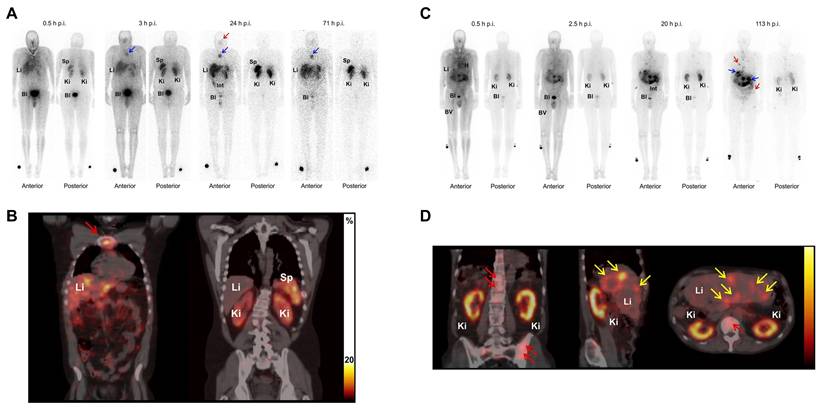

| [161Tb]Tb- | [161Tb]Tb-DOTATOC | SSTR-2/5 | Patient with paraganglioma (metastatic, well-differentiated, nonfunctional malignant) and neuroendocrine neoplasm of pancreas tail (metastatic, functional) | A first-in-human study demonstrated that [161Tb]Tb-DOTATOC, synthesized with high radiochemical purity, enabled high-quality SPECT/CT imaging and detection of small bone and liver metastases at low administered activities, showing favorable biodistribution in the liver, kidneys, spleen, and bladder without any reported adverse effects. | [177] |

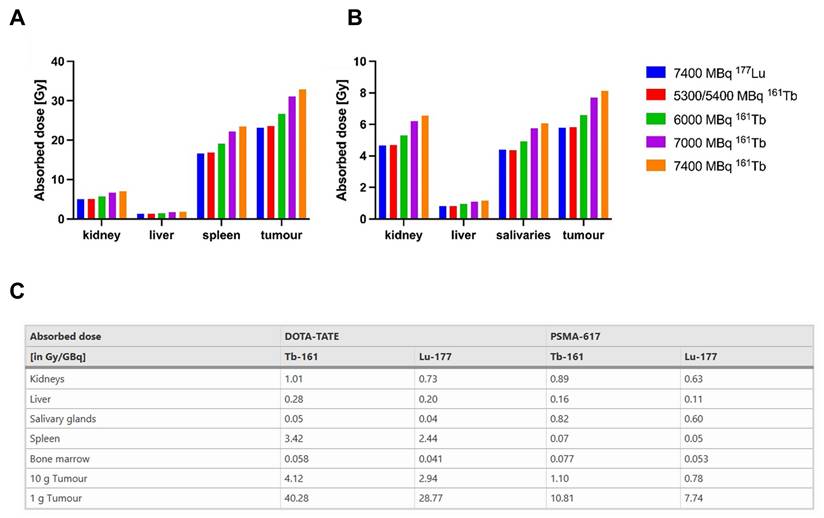

| [161Tb]Tb-DOTATATE | SSTR-2 | Patients with NET (SSTR positive) | Substitution of [177Lu]Lu- with [161Tb]Tb-DOTATATE Therapy boosts tumor absorbed dose per administered activity by approximately 40% (e.g., 2.9 → 4.1 Gy/GBq for a 10 g tumor), but to avoid increased kidney and bone marrow toxicity, the standard 7.4 GBq administered activity should be reduced to 5.3-5.4 GBq of [161Tb]Tb-DOTATATE. | [178] | |

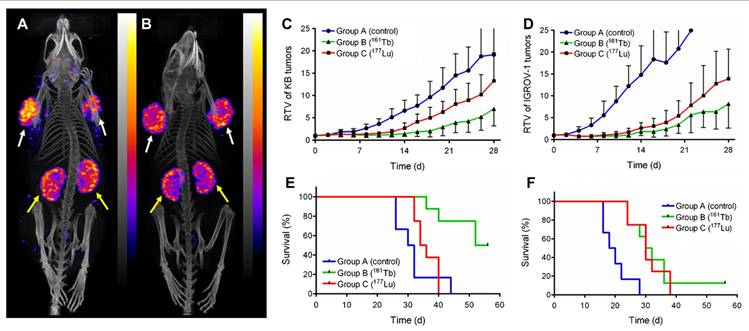

| [161Tb]Tb-DOTA-cm09 | FR | Human nasopharyngeal/ovarian cancer cell line (KB/IGROV-1) with FR-positive | [161Tb]Tb-DOTA-cm09 showed superior therapeutic efficacy than [177Lu]Lu-DOTA-cm09 both in vitro and in vivo, requiring significantly lower IC50 values in FR-positive tumor cells and delivering a higher tumor dose per administered activity (3.3 Gy/MBq vs. 2.4 Gy/MBq), while maintaining imaging capabilities and renal safety over a 6-month observation period. | [179] | |

| [161Tb]Tb-SibuDAB | PSMA (High affinity with albumin) | Human prostate cancer with PSMA-positive (PC3-PIP) | Compared to [177Lu]Lu- counterparts, [161Tb]Tb-SibuDAB and PSMA-I&T exhibited similar biodistribution but provided ~ 40% higher tumor-administered activities, with [161Tb]Tb-SibuDAB showing markedly enhanced tumor uptake (up to 69% IA/g) and therapeutic efficacy without observable toxicity in mice. | [180] | |

| Patients with mCRPC | [161Tb]Tb-SibuDAB achieved superior tumor retention and absorbed dose per administered activity delivery (6.5 Gy/GBq, Th = 135 h) compared with [177Lu]Lu-PSMA-I&T (2.6 Gy/GBq, Th = 67 h) in the first mCRPC patient, with no acute toxicity despite modestly higher kidney (2.6 vs. 1.2 Gy/GBq) and parotid (0.5 vs. 0.3 Gy/GBq) absorbed doses administered activities (PROGNOSTIC Phase I clinical trial, NCT06343038). | [181] | |||

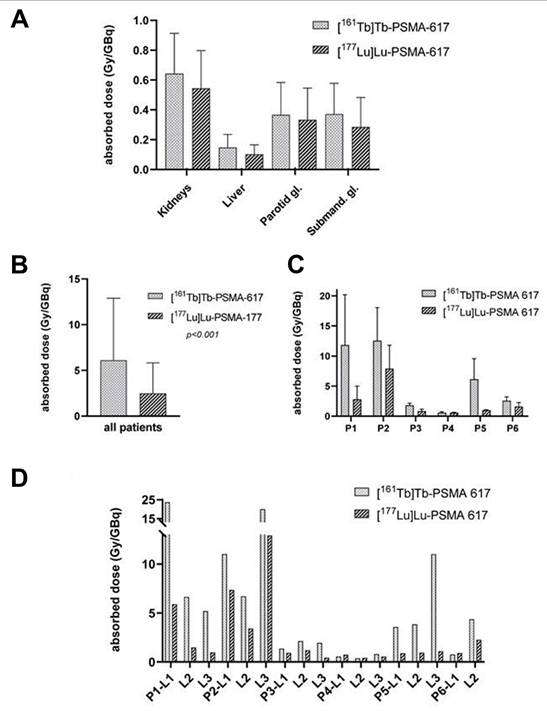

| [161Tb]Tb-PSMA-617 | PSMA | 6 patients with mCRPC | [161Tb]Tb-PSMA-617 showed superior efficacy in mCRPC patients, with a 2.4-fold increase in tumor absorbed dose per administered activity (6.10 ± 6.59 vs. 2.59 ± 3.30 Gy/GBq) and higher therapeutic indices for the kidneys (11.54 ± 9.74 vs. 5.28 ± 5.13 Gy/GBq) and parotid glands (16.77 ± 13.10 vs. 12.51 ± 18.09 Gy/GBq) (NCT04833517). | [182] | |

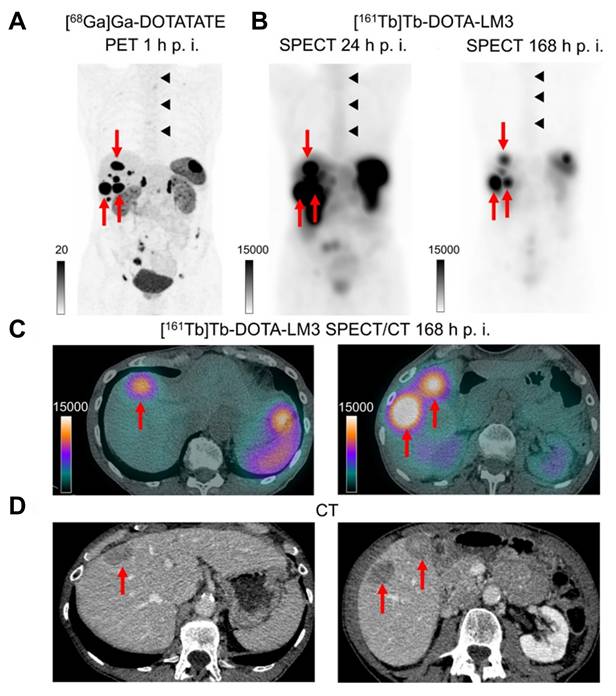

| [161Tb]Tb-DOTA-LM3 | SSTR-2 | Rat pancreas tumor cell line with SSTR-positive (AR42J) | Dual-isotope SPECT/CT imaging in AR42J tumor-bearing mice demonstrated that [161Tb]Tb- and [177Lu]Lu-labeled somatostatin analogues (DOTATOC and DOTA-LM3) exhibited indistinguishable PK and sub-organ biodistribution, with DOTA-LM3 showing significantly higher tumor uptake than DOTATOC (e.g., > 20% IA/g vs. ~10% IA/g at 4 h post-injection). | [183] | |

| Patient with ileal NET (metastatic, hormone-active [carcinoid syndrome]) | Following administration of 1 GBq [161Tb]Tb-DOTA-LM3, the patient's liver metastases demonstrated a tumor half-life of 130 h and an absorbed dose per administered activity of up to 39 Gy/GBq, while bone marrow, kidney, and spleen absorbed doses per administered activity were 0.31, 3.33, and 6.86 Gy/GBq, respectively, accompanied by a chromogranin A decrease of 163 µg/L and minimal hematologic toxicity (NCT05359146). | [184] |

MOT: Murine ovarian tumor; IA: Injected activity; APC: Alkylphophosphocoline; TNBC: Triple-Negative breast cancer; CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen; EpCAM: Epithelial cell adhesion molecule; EGFR: Epidermal growth factor receptor; GBM: Glioblastoma multiforme; AAF: Astrocyte with anaplastic foci; NET: Neuroendocrine tumor; NLS: Nuclear localization sequence; AML: Acute myeloid leukemia; DTPA: Diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid; HER2: Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; FR: Folate receptor; IC50: concentration required to inhibit cell growth by 50%; SSTR: Somatostatin receptor; mCRPC: metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.

4.1 Iodine-125 /or 123

4.1.1 125I- or 123I-5-iodo-2-deoxyuridine

5-Iodo-2′-deoxyuridine (IUdR), radiolabeled with [125I] or [123I], is a thymidine analog that integrates into DNA during replication and has been studied for its AE-mediated cytotoxic effects. In preliminary research, Chan et al. demonstrated that [125I]IUdR significantly elevated DNA DSBs and clonogenic cell death in V79 cells compared to [3H]TdR and [131I]IUdR, necessitating merely 0.0037 Bq per cell to induce three DSBs within 1 h, highlighting the markedly high LET effect of AE [157]. Sahu et al. reported the therapeutic efficacy of [125I]IUdR in a rat model of leptomeningeal metastases, where a single administration (18.5 GBq/head), daily injections for 5 days (3.7 GBq/day), and continuous infusion over 5 days (0.0185 GBq/h, totaling 18.5 GBq) significantly extended the median time to paralysis to 11, 12, and 15 days, respectively. Radioactivity was rapidly eliminated from all tissues, except for the thyroid and neoplastic cells proliferating in the spinal cord. This indicates that [125I]IUdR exerts a specific anticancer effect in the treatment of leptomeningeal illness [158]. Macapinlac et al. observed that in all four patients, [125/131I] showed a biexponential decay pattern after hepatic artery infusion and continued to accumulate in the tumor. They also estimated that 15-50% of the tumor cells were in the S-phase, suggesting suitability for IUdR incorporation [159]. In a mouse ovarian tumor (MOT) model, the AE-emitting radionuclide [123I]IUdR showed significant antitumor activity, improving mean survival and increasing absolute survival by 20% after 7 weeks following intraperitoneal (IP) administration. The observed survival benefit, even at the lowest administered activities, underscores the potent cytotoxicity of AE when effectively localized to tumor DNA [160]. Clinical investigations followed, including a phase 0 study with intracisternal [123I]IUdR demonstrating selective tumor targeting with favorable safety. Mariani et al. investigated the effect of radiosensitization in patients with hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer by intra-arterially administering [123I]IUdR, followed by systemic treatment with 5-fluorouracil (500 mg/m2) and 1-folinic acid (250 mg/m2), known as inhibitors of thymidylate synthase. Upon re-administration of [123I]IUdR one week later, the mean tumor uptake increased significantly from 9.1% to 14.0% injected activity (IA), representing an average enhancement in early tumor uptake of 78% [161]. These results collectively point to the promise of IUdR-based strategies in targeting proliferative tumor fractions, with administered activity timing and repetition as key variables.

4.1.2 [125I]DCIBzL

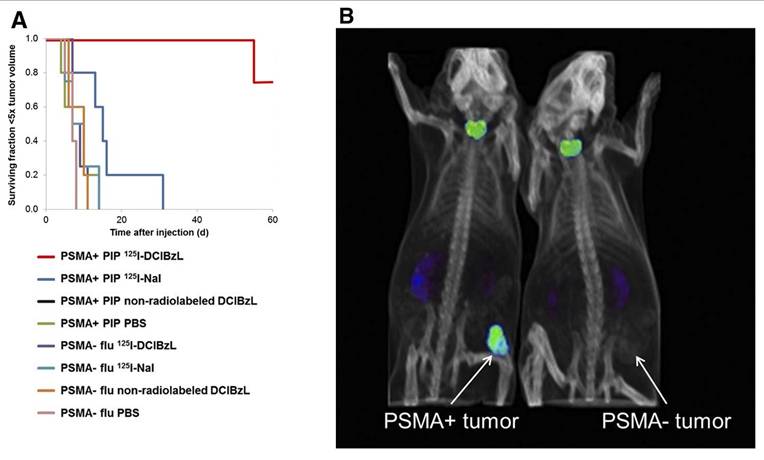

2-3-[1-carboxy-5-(4-[125I]iodo-benzoylamino)-pentyl]-ureido]-pentanedioic acid ([125I]DCIBzL) targets PSMA, a type II transmembrane glycoprotein that is highly overexpressed in prostate cancer. Kiess et al. showed that [125I]DCIBzL treatment caused more DNA damage and less clonogenic survival in PC3-PIP (PSMA-positive) cells than in PC3-Flu (PSMA-negative) cells. Correspondingly, tumor growth in PSMA-positive xenografts was significantly delayed, with only one mouse reaching 5 times the initial tumor volume within 60 days, whereas the median time to this threshold in PSMA-negative and other treatment groups was less than 15 days (log-rank test, P = 0.002) (Figure 4) [162]. Shen et al. showed that administering [125I]DCIBzL in activities between 18.5 and 111 MBq significantly delayed the appearance and growth of metastatic lesions in a micrometastatic prostate cancer model. The lesions manifested at a median of 4 weeks, in contrast to 2 weeks in the 0.37-3.7 MBq cohort [163]. The median survival for mice receiving ≥ 18.5 MBq rose to 11 weeks, compared to 6 weeks for the control group. Notably, there was no significant toxicity observed even 112 days after treatment, based on changes in body weight, urinalysis, or necropsy results showing that the [125I]DCIBzL is safer than PSMA-targeted α-emitting radionuclides. Dosimetry modeling results confirmed that the dose absorbed by nuclei of kidney cells was significantly lower than the dose absorbed by tumor cell nuclei due to the limited range of AE emission and limited intracellular uptake, demonstrating the favorable therapeutic window of [125I]DCIBzL. However, despite these promising outcomes, no additional studies or clinical applications have been reported thus far.

4.1.3 [125I]CLR1404

[18-(p-iodophenyl)octadecyl phosphocholine] is an alkyl-phosphocholine (APC) analogue that specifically targets lipid rafts. It preferentially infiltrates tumor cell membranes due to its affinity for microdomains abundant in sphingolipids and cholesterol. Grudzinski et al. demonstrated in a preclinical investigation that the ratio of absorbed dosage to tumors compared to absorbed radiation to bone marrow was favorable, with 0.261 Gy/MBq delivered to tumors and only 0.063 Gy/MBq to bone marrow. A single administration of 74 MBq [125I]CLR1404 enhanced the longevity of all treated animals to over 60 days and inhibited the growth of new triple-negative breast tumors by approximately 60% relative to controls. On day 35, lung metastases were markedly reduced. These results affirm the high therapeutic index and tumor specificity of CLR1404 as an AE-emitting radionuclide [164]. Encouraged by these promising results, several phase I and II clinical trials have been initiated or completed to evaluate the theranostic potential of radiolabeled CLR1404 in various malignancies; however, these studies primarily employed the β-emitting radionuclide [131I], and investigations utilizing AE-emitting radionuclides remain lacking [185-187].

In vivo antitumor efficacy and SPECT/CT imaging with [125I]DCIBzL in tumor xenograft mouse models. (A) Tumor growth delay curve after treatment with 111 MBq of [125I]DCIBzL or an equal amount of control compounds. (B) Small-animal SPECT/CT maximum-intensity-projection (MIP) images acquired in two different tumor xenograft mouse models (PSMA-positive: PC3-PIP; PSMA-negative: PC3-Flu;) at 24 h after [125I]DCIBzL treatment. Copyright© 2015 Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging.

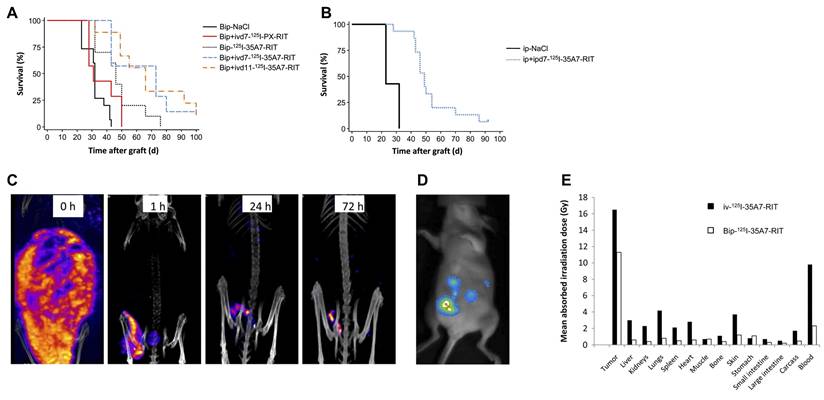

Intraperitoneal radioimmunotherapy (RIT) targeting small peritoneal carcinomatosis is conducted using high activities of the non-internalizing [125I]35A7. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves after administration of brief IP (Bip) or combined Bip and intravenous (IV) RIT in A431-bearing athymic nude mice model. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival rate after administration of Bip or combined Bip and IV 7-day RIT. (C) SPECT/CT images obtained immediately after injection (0 h) and 1, 24, and 72 h after lavage of the peritoneal cavity with saline in IP [125I]35A7 RIT (185 MBq) on day 4 post-implantation. (D) Bioluminescence images obtained 4 days post-implantation, immediately prior to RIT. (E) Graph of mean absorbed irradiation dose for brief IP [125I]35A7 RIT and IV [125I]35A7 RIT. Copyright 2010© Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging.

4.1.4 [125I]35A7 mAb