13.3

Impact Factor

Theranostics 2026; 16(7):3790-3825. doi:10.7150/thno.123550 This issue Cite

Review

Engineering polysaccharide nanoplatforms for glioblastoma theranostics: Bridging targeted therapy and advanced imaging

1. Department of Radiology, Institution of Radiology and Medical Imaging, Huaxi MR Research Center (HMRRC), Frontiers Science Center for Disease-Related Molecular Network, National Clinical Research Center for Geriatrics, State Key Laboratory of Biotherapy, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, China.

2. Psychoradiology Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Research Unit of Psychoradiology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, and Key Laboratory of Transplant Engineering and Immunology, NHC, Chengdu 610041, China.

3. Core Facility of West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, China.

4. Animal Imaging Core Facilities, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, China.

5. Xiamen Key Lab of Psychoradiology and Neuromodulation, Department of Radiology, West China Xiamen Hospital of Sichuan University, Xiamen 361021, China.

*Dr. Xiaoming Wang and Qing Yang contributed equally to this study.

Received 2025-8-11; Accepted 2025-12-29; Published 2026-1-14

Abstract

Glioblastoma (GBM) is an aggressive brain tumor characterized by limited therapeutic efficacy and challenges in accurate imaging, largely due to its invasive growth, drug resistance, and the restrictive blood-brain barrier (BBB) hindering the delivery of both therapeutic and diagnostic agents. Current GBM treatments and imaging approaches often suffer from insufficient agent penetration into the tumor. Additionally, they frequently exhibit toxicity or poor signal-to-noise ratios. Polysaccharide (PSC)-based polymers, with their inherent biocompatibility, biodegradability, and versatile chemical modifiability, offer a promising platform to overcome these limitations. These natural polymers can be engineered into sophisticated nanocarriers that enhance BBB traversal, enable targeted tumor accumulation of therapeutic payloads and imaging agents Furthermore, they facilitate controlled drug release and improve diagnostic signal generation. Consequently, PSC-based systems can improve therapeutic efficacy and enhance diagnostic accuracy for tumor visualization. Furthermore, they reduce systemic side effects and support multimodal strategies, ranging from single-modality interventions to integrated theranostic systems. This review aims to comprehensively discuss recent advancements, current challenges, and future perspectives of PSC-based nanomedicines in GBM therapy and imaging.

Keywords: GBM, imaging, nanomedicines, polysaccharide polymer

1. Introduction

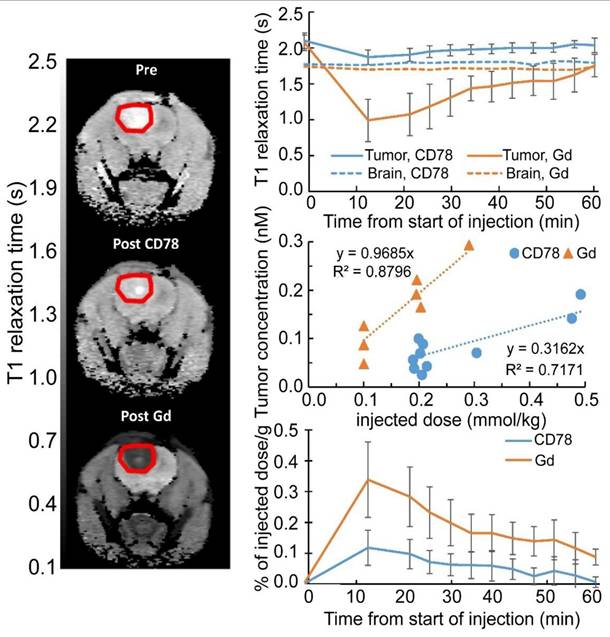

GBM presents a formidable clinical challenge due to its invasive growth, inherent resistance to standard therapies, and the complex physiological obstacle posed by the BBB [1] (Figure 1). In high-grade gliomas, the BBB evolves into a heterogeneous blood-brain tumor barrier (BBTB), the integrity of which is a subject of considerable debate and a critical factor for drug delivery. This complexity necessitates a clear distinction between the penetration capabilities of small diagnostic agents versus larger therapeutic nanocarriers. For instance, diagnostic agents like gadolinium-based contrast media or ultra-small imaging nanoparticles (NPs) (e.g., <5 nm) can exploit localized structural compromises in the BBTB. The contrast enhancement observed in T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) directly visualizes regions where the barrier has ruptured, confirming extravasation into the tumor core. However, the level of compromise sufficient for this enhancement is often insufficient for the robust, uniform penetration of larger therapeutic NPs, which typically exceed 50 nm.

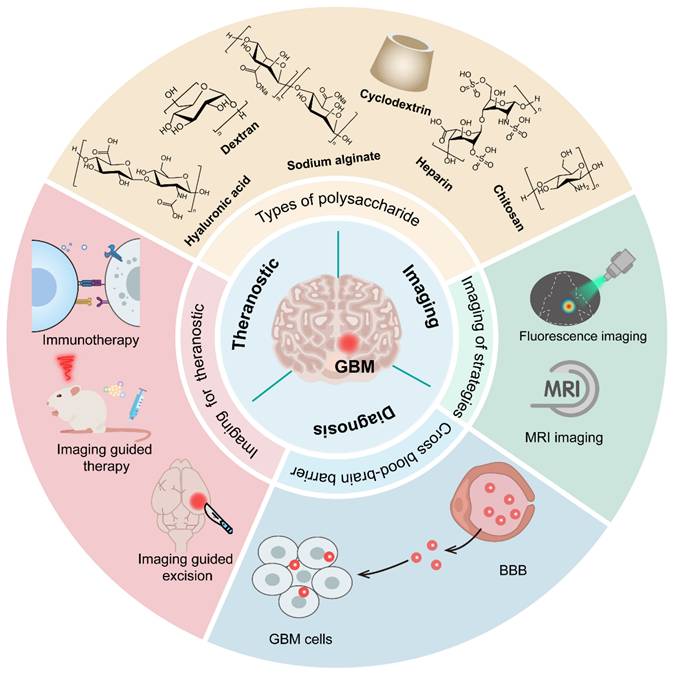

Smart PSC-based nanomedicines (e.g., sodium alginate, chitosan, cyclodextrin, heparin, dextran, etc.) for imaging and therapeutic applications in GBM. Mainly involves (1) crossing the BBB for enhanced accumulation of therapeutic agents and imaging probes at GBM sites; (2) multimodal imaging, including fluorescence imaging and MRI, to support tumor staging, diagnosis, and boundary delineation; (3) theranostic integration, enabling imaging-guided precise treatments (e.g., surgical resection) and immunotherapy.

The extent of BBB compromise in GBM is highly variable. While high-grade gliomas are characterized by neo-angiogenesis and a "leaky" vasculature in the tumor core-driven by elevated vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and reduced tight junction (TJ) proteins-this breakdown is not uniform. Conflicting studies reveal that vessels in the peritumoral region, where recurrence often originates, frequently retain structural components resembling the healthy BBB, such as intact TJs and normal pericyte coverage. This heterogeneity gives rise to the concept of the 'residual BBTB,' which refers to the anatomical and functional regions within and surrounding the malignant tissue, particularly at the invasive margins, where barrier integrity remains partially or fully intact. This residual barrier, composed of tightly controlled endothelial TJs, astrocyte end-feet, and the basal lamina, actively shields infiltrating tumor cells from systemic therapeutics. The presence of this residual BBTB severely restricts the reliability of the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect for GBM therapy. While the passive accumulation of NPs via the EPR effect can occur in the highly disrupted tumor core, it is largely ineffective at the tumor rim, preventing therapeutic agents from reaching the most invasive cell populations. Therefore, reliance on passive delivery is generally insufficient for GBM eradication. Overcoming these obstacles-including inadequate transport across the residual BBTB, poor targeting specificity, and systemic toxicity of potent agents is crucial. This necessitates the development of sophisticated carrier systems capable of precise tumor targeting and controlled payload release.

PSC-based nanoplatforms have emerged as highly promising candidates for addressing these multifaceted challenges in GBM management. PSCs, including widely studied examples like chitosan, hyaluronic acid (HA), dextran, and alginate, as well as various plant-derived PSCs, offer a unique combination of inherent biocompatibility, biodegradability, and abundant reactive groups for versatile chemical modification [2]. These characteristics allow for the rational design of PSC-based carriers that can be functionalized with targeting ligands (e.g., peptides, antibodies) or engineered to respond to specific stimuli within the tumor microenvironment. Such modifications facilitate improved specificity of agent accumulation in GBM cells and enable controlled release of diagnostic or therapeutic payloads. Through their tunable physicochemical properties, PSC-based systems serve as versatile platforms that can be tailored for distinct applications, either as dedicated diagnostic probes or therapeutic carriers [3]. Beyond these single-modality functions, advanced engineering allows for the integration of both imaging agents and therapeutic payloads into a single construct, thereby actualizing true theranostic approaches [4, 5]. It is critical to distinguish these integrated theranostic systems, which simultaneously deliver therapeutic payloads and diagnostic signals, from nanocarriers designed exclusively for a single modality. While single-function systems optimize either sensitivity (imaging) or payload capacity (therapy), true theranostic platforms must balance both, often requiring more complex engineering to prevent signal interference or premature drug release. Consequently, these nanoformulations hold the potential to significantly improve diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic outcomes while minimizing off-target effects. Furthermore, beyond their utility as delivery vehicles, many PSCs possess inherent immunostimulatory properties or can be modified to modulate the tumor immune microenvironment, offering an additional avenue to enhance anti-GBM responses [6].

Given the significant advantages and versatile nature of PSC nanoplatforms in addressing the critical issues faced in GBM diagnosis and treatment, this review aims to comprehensively summarize the recent advancements in the field. We will delve into the various types of PSCs being explored, such as chitosan, HA, dextran, alginate, and other emerging PSCs. The review will detail their rational design strategies and highlight their applications in enhancing imaging modalities for improved GBM diagnosis, augmenting the efficacy of diverse therapeutic strategies (including chemotherapy, gene and RNA therapy, and combination therapies), and developing integrated theranostic systems. By focusing on these aspects, this review seeks to underscore the promise of PSC-based nanomedicines in shaping the next generation of management strategies for GBM.

2. Overcoming the BBB for GBM Therapy: Nanocarrier Strategies and the Role of PSCs

A major obstacle in GBM therapy is the efficient delivery of anticancer agents across the BBB. The tight junctions characteristic of the BBB, formed by endothelial cells, pericytes, and astrocytes, significantly hamper the entry of many therapeutic compounds, particularly large or hydrophilic chemotherapeutics, into the brain parenchyma [7, 8]. This barrier meticulously regulates the passage of substances, protecting the central nervous system (CNS) but concurrently limiting the efficacy of systemic treatments for brain malignancies. Nanocarrier-based systems represent a promising avenue to surmount this biological obstruction, aiming to improve drug concentrations at the tumor site while minimizing systemic toxicity.

Nanocarriers can employ several mechanisms to facilitate their passage across the BBB. In instances where the BBB integrity is compromised, nanocarriers, typically ranging from 1 to 100 nm in size (many clinically relevant NPs are larger than 100 nm), may utilize passive diffusion to enter the brain tissue. This is often the case for regions of disrupted vasculature that are associated with the GBM microenvironment changes (a phenomenon sometimes related to the enhanced permeability and retention, or EPR effect). However, the heterogeneity of BBB disruption in GBM necessitates more sophisticated approaches for consistent and widespread delivery.

For areas where the BBB remains more intact, active transport mechanisms are crucial. These include adsorptive-mediated transcytosis (AMT), which is often triggered by electrostatic interactions between cationic nanocarriers and the negatively charged glycocalyx and phospholipid head groups on the luminal surface of brain capillary endothelial cells. Carrier-mediated transport (CMT) offers another route, utilizing endogenous transporters designed for essential nutrients like glucose, amino acids, and nucleosides, although this pathway is generally more suited for smaller molecules or drugs that structurally mimic these native substrates. A more widely exploited active mechanism for nanocarriers is receptor-mediated transcytosis (RMT). This highly specific pathway involves the binding of ligands, purposefully conjugated to the nanocarrier surface, to receptors abundantly expressed on BBB endothelial cells. Commonly targeted receptors include those for transferrin (TfR), low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1), lactoferrin (LfR), and insulin receptors [9]. Upon ligand binding, the nanocarrier is internalized via endocytosis, transported across the endothelial cell, and subsequently exocytosed into the brain interstitium.

Beyond these direct transport mechanisms, stimuli-responsive nanocarriers present another sophisticated strategy. These systems are engineered to remain relatively inert and stable in systemic circulation, minimizing premature drug release or off-target interactions. However, these nanocarriers undergo specific changes upon encountering specific triggers within the brain microenvironment. Triggers include the acidic pH characteristic of tumor tissues (around pH 6.5 or lower), altered redox gradients (e.g., elevated glutathione levels), or the presence of specific enzymes like matrix metalloproteinases. Externally applied stimuli, such as ultrasound or magnetic fields, can also induce these changes. These changes can include drug release, conformational alteration leading to enhanced cell uptake, or degradation of the carrier matrix. This targeted response thereby enhances the spatiotemporal control of drug delivery across the BBB or within the brain tissue itself, aiming to maximize therapeutic efficacy while reducing systemic side effects [3].

Among the materials explored for traversing the BBB, PSCs (e.g., chitosan, HA, dextran, alginate) offer distinct advantages due to their inherent biocompatibility, biodegradability, and versatile chemical modifiability [2, 10]. Crucially, specific PSCs leverage distinct transport mechanisms to overcome the BBB and BBTB. Chitosan, a cationic polymer, utilizes AMT; its positive charge facilitates electrostatic interactions with the negatively charged endothelial luminal surface, promoting transcellular passage [3]. Conversely, Hyaluronic Acid (HA) engages RMT by specifically binding to CD44 receptors, which are overexpressed on both activated brain endothelial cells and GBM cells, thereby enabling dual BBB-traversal and tumor targeting. Other PSCs, such as dextran, serve as excellent stealth coatings to prolong circulation or can be functionalized with external ligands (e.g., transferrin, angiopep-2) to induce RMT [9]. By tailoring these physicochemical properties—specifically size (optimally 30-150 nm), surface charge, and ligand density—PSC nanocarriers can be engineered to maximize brain accumulation while minimizing systemic clearance [11, 12].

The successful transit of PSC nanomedicines across the BBB and their subsequent therapeutic action are critically dependent on the meticulous control and optimization of their physicochemical properties and functional attributes. By tailoring nanocarrier size, surface charge, ligand attachments, and responsiveness to stimuli, researchers aim to improve BBB transport, enhance drug accumulation in GBM tissue, and control drug release kinetics, thereby maximizing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing adverse effects [4, 11]. Precise control of nanoparticle size is vital for effective BBB penetration and favorable pharmacokinetics. While smaller PSC-based NPs (e.g., <100 nm) may more readily diffuse through disrupted tight junctions or fenestrations in leaky BBB regions and are generally favored for endocytic uptake, extremely small constructs (<10 nm) can suffer from rapid renal clearance, leading to a significantly reduced circulation time and insufficient opportunity for BBB interaction [12, 13]. Conversely, very large NPs (>200-300 nm) may be rapidly cleared by the RES or may not efficiently cross the BBB even via active transport. Therefore, many PSC nanocarriers are designed with a diameter in the range of 30-150 nm to strike an optimal balance between prolonged systemic residence, avoidance of rapid clearance, and effective brain diffusion or transport.

The surface charge of PSC nanocarriers also significantly influences their interaction with the BBB and systemic fate. Moderately cationic chitosan-based carriers, for example, can leverage their positive charge to encourage AMT. However, an excessively high positive charge might trigger significant nonspecific binding to plasma proteins and blood cells, leading to aggregation, opsonization, and rapid immune clearance, or even endothelial toxicity. Strategies to modulate surface properties and mitigate these issues include coating with neutral, hydrophilic polymers like polyethylene glycol (PEG), known as PEGylation, which creates a steric barrier reducing protein adsorption and prolonging circulation. Partial grafting with other PSCs like HA can also serve a similar purpose or introduce specific targeting functionalities.

The attachment of specific ligands to the surface of PSC nanocarriers is a cornerstone strategy to promote active transport across the BBB via RMT and to enhance tumor cell recognition. Commonly employed ligands include transferrin (Tf), which binds to the highly expressed TfR on brain endothelial cells; angiopep-2, a peptide that targets LRP1; and various antibodies or antibody fragments directed against BBB-specific receptors. For instance, modifications of chitosan or HA with transferrin have been shown to improve NP passage across in vitro and in vivo BBB models. Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs), such as TAT peptide or penetratin, can also be conjugated to PSC matrices to encourage deeper tissue uptake and accumulation in glioma sites, possibly by transiently modulating tight junction integrity or by promoting direct membrane translocation or enhanced endocytosis. Multiple reports indicate that such peptide-functionalized carriers exhibit greater fluorescence detection in the brain or more potent anticancer responses in glioma models compared to their unmodified counterparts, emphasizing the therapeutic advantage of active ligand conjugation [14, 15].

Incorporating stimuli-responsive elements into PSC nanocarriers allows for controlled drug release or activation specifically at the tumor site, triggered by the unique tumor microenvironment or by external interventions. For pH-responsive platforms, linkages that are stable at physiological pH (7.4) but hydrolyze or alter conformation in the acidic conditions of GBM tissues (pH ~6.5 or lower intracellularly) are employed. This prevents premature drug leakage during circulation and ensures site-specific activation. For example, mesoporous silica NPs coated with PSC layers have demonstrated significantly higher drug release under acidic conditions compared to neutral pH. Magnetic/pH-sensitive graphene oxide-chitosan microspheres loaded with temozolomide (TMZ) showed nearly doubled drug release at pH 4.5 relative to neutral conditions, a release further amplified by a moderate external magnetic field [16]. Redox-sensitive PSC materials leverage the significantly elevated GSH levels found in tumor cells compared to the extracellular environment. These carriers often incorporate disulfide linkages (-S-S-) within their structure or as crosslinkers. These bonds remain stable in the low-GSH environment of the bloodstream but are rapidly cleaved in the high-GSH reductive intracellular milieu of cancer cells, leading to carrier disassembly and burst-like drug release [17]. For instance, disulfide-crosslinked chitosan or dextran NPs can be designed to selectively deliver chemotherapeutic agents upon entering tumor cells. One study utilized a porphyrin-based metal-organic framework (MOF) crosslinked with HA that responded to high GSH levels in GBM tissue, releasing porphyrin-MOF NPs capable of generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) under ultrasound irradiation for sonodynamic therapy, and co-delivering L-cysteine to enhance tumor cell apoptosis. However, variations in redox gradients among individual patients and different tumor regions remain a challenge for achieving reproducible therapeutic outcomes with these systems. Furthermore, a critical limitation observed across chitosan studies is the trade-off between BBB penetration and toxicity. While increasing the degree of deacetylation and positive charge enhances absorptive-mediated transcytosis, it concurrently increases the formation of a protein corona in the bloodstream. This leads to rapid clearance by the reticuloendothelial system (RES) and potential neurotoxicity, a contradiction that explains why high-charge formulations often succeed in vitro but fail to maintain therapeutic concentrations in orthotopic animal models.

Exogenous triggers such as ultrasound (US) and magnetic fields further broaden the therapeutic potential. Focused ultrasound, often in conjunction with microbubbles, can transiently and locally disrupt the BBB, improving NP penetration. US can also stimulate faster drug release from carriers sensitive to mechanical or thermal energy. For instance, PSC-based silica carriers loaded with doxorubicin (DXR) displayed accelerated release upon ultrasonic stimulation, contributing to higher intratumoral accumulation and reduced cardiotoxicity. Magnetic fields can guide PSC-coated magnetic NPs (e.g., iron oxide cores) to the tumor site or trigger drug release. In magnetothermal therapy, these magnetic elements generate localized heat under an alternating magnetic field (AMF), directly damaging glioma cells (typically at 42-45°C) and enabling temperature-dependent drug release from thermosensitive PSC carriers. This hyperthermia can also increase tumor permeability and sensitize cells to chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Iron-containing PSC-NPs can also participate in chemodynamic therapy via the Fenton reaction, where released iron ions catalyze the conversion of endogenous H₂O₂ into highly toxic hydroxyl radicals, specifically within the acidic tumor microenvironment.

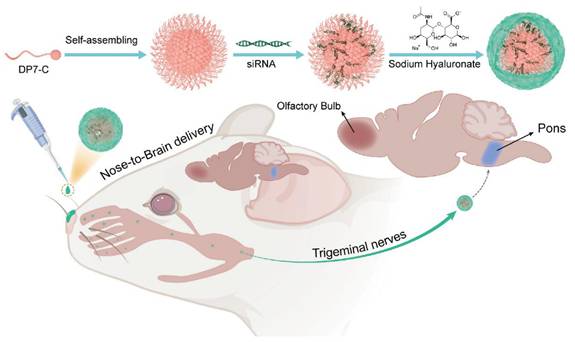

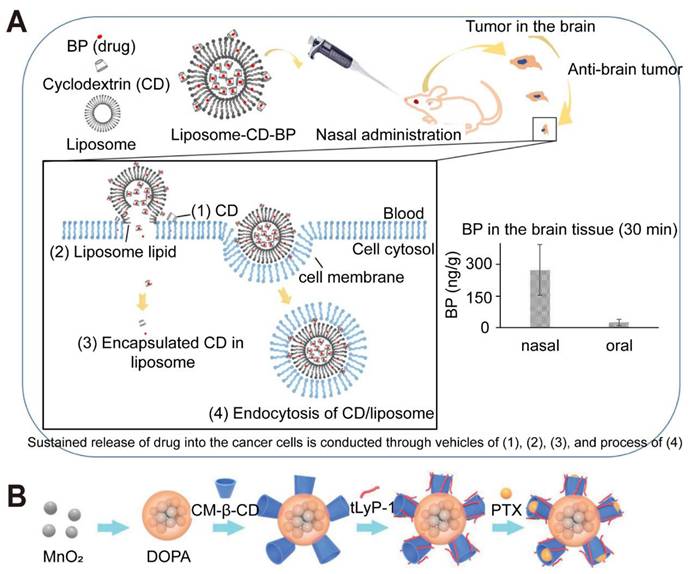

Beyond systemic administration, alternative delivery routes are being explored for PSC nanomedicines. Intranasal delivery, for example, exploits the direct nose-to-brain pathways (olfactory and trigeminal nerves) to bypass the BBB to some extent. Chitosan's mucoadhesive properties are particularly beneficial here, prolonging residence time in the nasal cavity and enhancing absorption. Chitosan-decorated poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) NPs loaded with carmustine (BCNU) nearly tripled brain drug levels in rats via intranasal administration compared to intravenous injection [18]. Similarly, β-cyclodextrin-chitosan coatings on gold-iron oxide NPs demonstrated efficient intranasal uptake and led to marked survival benefits in mouse glioma models [19]. Localized delivery using PSC-based hydrogels implanted into post-resection cavities is another promising strategy. These hydrogels can act as depots for sustained, localized release of chemotherapeutics or immunomodulators, minimizing systemic toxicity and targeting residual tumor cells. For instance, a semi-synthetic PSC hydrogel loaded with ruxolitinib provided sustained release for 14 days and showed strong in vitro GBM cell-growth inhibition [20]. Cellulose nanocrystal hydrogels delivering paclitaxel (PTX) have also demonstrated measurable tumor suppression [21].

GBM is characterized by pronounced inter- and intratumoral heterogeneity, which includes variations in BBB integrity, receptor expression profiles, and microenvironmental conditions across different tumor regions and among patients [22]. Effective therapeutic strategies must therefore be adaptable and capable of addressing drug delivery to both intact and partially leaky BBB regions, as well as targeting diverse tumor cell populations. To enhance specificity and efficacy, dual-targeting approaches are being developed. These equip PSC nanocarriers with one ligand for BBB passage (e.g., transferrin or angiopep-2) and another for binding to receptors overexpressed primarily on tumor cells (e.g., integrin-binding RGD peptides for neoangiature or glioma cells, or CD44-binding HA for glioma cells). This strategy aims to improve drug accumulation and retention specifically within invasive glioma cells, thereby enhancing overall therapeutic efficacy [23, 24]. For example, HA-based nanomicelles modified with angiopep-2 and incorporating a hypoxia-sensitive moiety for triggered release have been developed. One such system, also utilizing Tween 80 for enhanced BBB passage, achieved a 7.6-fold increased transport across an in vitro BBB model compared to formulations lacking Tween 80 [25].

PSC nanocarriers are also being engineered as theranostic platforms, integrating imaging and therapeutic functions into a single complex. Dextran-coated iron oxide NPs delivering antisense oligonucleotides permit concurrent MRI tracking and gene silencing in GBM [26]. Multifunctional chitosan-coated magnetite graphene oxide systems, grafted with gastrin-releasing peptide ligands and loaded with doxorubicin, demonstrated decreased tumor burden under an external magnetic field, showcasing combined targeting, imaging capability, and therapy [27].

PSC nanocarriers are advancing gene and RNA therapy for GBM by securely encapsulating and transporting nucleic acids such as siRNA, miRNA, or plasmid DNA. The inherent biocompatibility of PSCs like chitosan and HA typically reduces immunogenic concerns associated with viral vectors. Surface modifications, including PEGylation or the addition of targeting ligands like transferrin, further extend circulation time, curb nonspecific adsorption, and improve selectivity for glioma cells [28, 29].

Furthermore, some PSCs (e.g., certain β-glucans, chitosan) possess intrinsic immunostimulatory properties, which can be leveraged to augment the effects of co-delivered immunotherapeutic agents like checkpoint inhibitors, cytokines, or tumor-associated antigens. Such carriers can accumulate in GBM tissue, help activate local anti-tumor immune responses by engaging innate immune cells, and synergize with conventional chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Hybrid constructs incorporating immunomodulators like CpG oligodeoxynucleotides within PSC matrices are also being explored [30].

Ensuring the safety of these nanoplatforms is paramount for clinical translation. This necessitates thorough preclinical evaluation, including comprehensive acute and chronic toxicity studies, immunogenicity assessments, and detailed biodistribution profiles. Noninvasive imaging techniques, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and near-infrared (NIR) fluorescence imaging, are invaluable tools for monitoring carrier localization, BBB crossing efficiency, tumor accumulation, and overall safety profiles in vivo.

As research in this domain continues to advance, PSC-based nanomedicines hold significant promise for transforming GBM management. They offer a versatile platform that can be engineered for systemic or local administration, employed as standalone delivery systems, or used in combination with other therapeutic modalities such as immunotherapies, focused ultrasound, or radiotherapy [5]. Achieving deeper penetration into the brain parenchyma, beyond the often-compromised tumor core and into invasive tumor margins, requires a holistic approach. This involves capitalizing on passive diffusion where possible, but more critically, harnessing receptor-mediated uptake mechanisms and exploiting environmental triggers or external stimuli to concentrate anticancer agents within GBM cells while minimizing off-target toxicity. The systematic assessment and optimization of all relevant design factors—including PSC type and molecular weight, nanoparticle size and morphology, surface charge and hydrophilicity, ligand choice and density, drug loading capacity, and release kinetics—are crucial for maximizing BBB penetration and subsequent tumor uptake and therapeutic effect [10]. Continued in vivo experiments in increasingly sophisticated and clinically relevant orthotopic GBM models are essential to elucidate how these multifaceted parameters collectively influence therapeutic efficacy and to validate safety. Ongoing efforts will likely focus on refining ligand specificity, developing multi-stimuli responsive systems for even greater spatiotemporal control, integrating combination therapies (e.g., chemo-immunotherapy or chemo-gene therapy), and establishing standardized, reproducible manufacturing and characterization protocols. By meticulously refining each aspect of PSC-driven delivery and rigorously validating their performance, these nanocarriers are poised to remain at the forefront of innovative strategies for crossing the BBB and offering safer, more effective treatments for the formidable challenge of GBM.

3. PSC-Based Strategies for GBM Imaging

PSC-based carriers are increasingly explored for GBM diagnostics, effective imaging. However, is fundamentally limited by the BBB, a highly selective interface that restricts the passage of most agents from systemic circulation into the brain parenchyma [31-33]. Consequently, significant research focuses on engineering nanocarriers, particularly PSCs, to leverage biological transport mechanisms. These biocompatible and structurally versatile macromolecules can be functionalized to cross the BBB and are readily conjugated with imaging agents—such as fluorescent dyes, gadolinium (Gd)-based contrast agents, or NPs—to enable sensitive, noninvasive tracking and improve tumor boundary delineation [34-36].

As detailed in Section 2, PSC nanoplatforms traverse the BBB primarily by leveraging RMT (targeting receptors like TfR1, LRP-1, and GLUT1) or AMT strategies [37-42]. Biomimetic strategies, including hyaluronic acid (HA) coatings to target CD44 on GBM cells [43] or cell-membrane cloaking (e.g., RBCs, EVs) to evade immune detection, also enhance delivery [44]. Additionally, physical methods, notably focused ultrasound (FUS) with microbubbles, can transiently disrupt the BBB to significantly boost nanocarrier accumulation [45].

Once across the BBB, these PSC platforms deliver diagnostic payloads for various imaging modalities, dominated by Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and optical imaging (OI) due to their clinical maturity and safety (Table 1) [46]. MRI remains the clinical gold standard, providing high-contrast anatomical information. PSCs incorporating superparamagnetic iron oxide NPs (IONPs) or Gd-based agents enable enhanced T1-weighted or T2-weighted imaging, allowing for precise tracking of nanoparticle accumulation and longitudinal monitoring of treatment response [47, 48]. Complementarily, OI, particularly Near-Infrared (NIR) fluorescence, is vital for real-time intraoperative guidance, offering the high spatial resolution needed to accurately delineate tumor margins and ensure maximal safe surgical resection [49, 50].

PSC-Metal Hybrid Imaging Probes

| Approach/Method Name | Nanoparticle Composition | Targeting Moiety | Imaging Modality & Contrast | Therapeutic Agent | Validation Model | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Folic Acid & Hyaluronic Acid Coated SPIONs | SPION core; Hyaluronic acid & Folic acid shell | Hyaluronic acid; Folic acid | MRI (T2) | Intrinsic cytotoxicity | Glioma & adenocarcinoma cells; hepatocytes | Kasprzyk et al. [62] |

| Dextran-Coated SPIONs for RNA Delivery | Iron oxide core; Dextran & Cy5.5 shell | Passive (size-based) | MRI; Optical (Cy5.5) | Antisense oligonucleotide (anti-miR10b) | Orthotopic GBM mouse model | Kim et al. [26] |

| Chitosan-Dextran Hybrid SPIONs (CS-DX-SPIONs) | SPION core; Chitosan-dextran hybrid shell | Chitosan (charge-mediated) | MRI (T2) | None (potential carrier) | U87, C6, HeLa cells; Orthotopic C6 glioma rat model | Shevtsov et al. [66] |

| Magnetic Ternary Nanohybrid (MTN) for MSC Transfection | SPION core; Hyaluronic acid & cationic polymer shell | Hyaluronic acid & Magnetic force (for MSCs) | MRI | Gene delivery (TRAIL plasmid) to MSCs | Human MSCs; U87MG orthotopic xenograft model | Huang et al. [63] |

| Quantum Dot-Biopolymer-Drug Nanohybrids (ZnS@CMC-DOX) | ZnS quantum dot core; Carboxymethylcellulose shell | None | Optical (fluorescence) | Doxorubicin | GBM & healthy cells | Mansur et al. [70] |

| Amino Acid Modified PSC-Capped QDs | AgInS2 quantum dot core; CMCel-L-cysteine or -Poly-L-arginine shell | L-cysteine/poly-L-arginine | Optical (fluorescence) | None | Glioma cells | Carvalho et al. [71] |

| Chlorotoxin-Conjugated Magnetic NPs (IONP-PTX-CTX-FL) | Iron oxide core; PEG, Cyclodextrin, CTX, Fluorescein shell | Chlorotoxin | MRI; Optical (fluorescein) | Paclitaxel | GBM & drug-resistant GBM cells | Mu et al. [69] |

| Mechanism Study of Poly-l-lysine Mediated MNP Uptake | Magnetic NP core; Dextran or Poly-l-lysine shell | Poly-l-lysine | N/A | None | Human glioma & HeLa cells | Siow et al. [68] |

| Low-Molecular-Weight Hyaluronic Acid-SPIONs (Theranostic) | Fe3O4 core; Low-MW hyaluronic acid shell | Low-MW Hyaluronic acid | MRI (T2*) | Intrinsic cytotoxicity (34% inhibition) | U87MG GBM & NIH3T3 fibroblast cells | Chang et al. [64] |

| Low-Molecular-Weight Hyaluronic Acid-SPIONs (Diagnostic) | Fe3O4 core; Low-MW hyaluronic acid shell | Low-MW Hyaluronic acid | MRI (T2*) | None | U87MG GBM & NIH3T3 fibroblast cells | Huang et al. [65] |

Emerging modalities are increasingly integrated into PSC designs to provide functional and quantitative data. Positron Emission Tomography (PET) and Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) offer exceptional sensitivity and unlimited tissue penetration, overcoming the depth limitations of OI [51]. By stabilizing radiotracers, PSCs can map molecular processes, such as amino acid uptake [18F]-FET PET), to assess tumor metabolism undetected by structural MRI [52, 53]. Hybrid PET/MRI systems combine the anatomical resolution of MRI with the quantitative sensitivity of PET [54]. Furthermore, acoustic modalities offer unique capabilities. Photoacoustic imaging (PAI) leverages PSCs carrying strong light absorbers (e.g., gold NPs) to generate high-resolution, non-invasive images [55]. Ultrasound (US) serves a dual role: beyond its use in FUS-mediated BBB disruption, it can be used for imaging or as an external trigger for controlled drug release from engineered PSC nanobubbles [56, 57].

In summary, while MRI and OI remain the cornerstones of clinical translation for PSC-based imaging, the field is advancing toward sophisticated multimodal systems. These platforms integrate the quantitative metabolic insights of PET/SPECT and the functional capabilities of photoacoustic and ultrasound imaging [58, 59]. The modular nature of PSCs allows for the incorporation of BBB-targeting ligands, multiple imaging moieties, and stimuli-responsive features (e.g., pH/redox sensitivity) to boost signal strength specifically within the tumor. This integrated approach aims to overcome the limitations of single-modality imaging, enabling more precise diagnosis, real-time intervention, and rigorous monitoring of therapeutic outcomes in GBM [60, 61].

3.1 PSC-Based Probes for Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Multiple studies demonstrate that HA-conjugated IONPs exhibit superior T2-weighted contrast compared to non-targeted controls, directly correlated to their accumulation in CD44-overexpressing GBM cells [62]. Another investigation used HA conjugation to low-molecular-weight SPIONs, demonstrating strong T2* signal changes that correlated with significant NP accumulation in GBM cells but minimal uptake in healthy fibroblasts [65]. Shared characterization methods typically include DLS, zeta potential, and various spectroscopic analyses, while in vitro experiments commonly employ U87 glioma cells to confirm preferential internalization [63, 64].

Several HA-coated IONP systems feature similar size distributions, generally ranging from 10 to 100 nm, and exhibit low cytotoxicity in vitro. Dual-targeting ligands, such as folic acid, can further enhance receptor-mediated binding to specific GBM subpopulations, although other designs leverage HA alone or in combination with surface peptides to improve BBB crossing or intratumoral penetration [65]. Despite various promising in vitro results, most studies rely on small animal models that may not capture the complexity of human gliomas, highlighting the importance of larger-scale investigations. Exploiting the CD44-mediated uptake and magnetically responsive cores of these HA-based iron oxide probes shows promise for precise tumor visualization, targeted drug delivery, and potentially broader clinical applications. Crucially, a distinction must be made here: while many HA-iron oxide formulations serve solely as passive T2-weighted contrast agents, true theranostic designs further capitalize on the magnetic core for hyperthermia or conjugate chemotherapeutics (e.g., Doxorubicin) to the PSC shell. This transition from a diagnostic probe to a theranostic agent enables the simultaneous monitoring of tumor boundary reduction and therapeutic response. Future work might delineate strategies for integrating multiple targeting moieties or therapeutic payloads to amplify their imaging and cytotoxic effects, but efforts must address safety and pharmacokinetics in clinically relevant settings (Figure 2A-C) [62, 63].

Chitosan and dextran have also been widely adopted to stabilize, functionalize, or crosslink iron oxide cores for MRI-guided GBM interventions. Dextran coatings often confer colloidal stability, reduce cytotoxicity, and allow traceability under MRI. For example, crosslinked dextran-coated IONPs loaded with antisense oligonucleotides enabled image-guided tracking and showed therapeutic potential in orthotopic glioma models. Another study assessed Chitosan-dextran superparamagnetic NPs in rodent glioma models, reporting a uniform particle size of about 55 nm and significant T2 contrast enhancement in the tumor region [64]. These findings indicate that Chitosan can significantly improve cellular uptake and tumor retention, although its elevated charge requires optimization to mitigate potential off-target effects.

Other works have examined chitosan alone as a coating agent for Fe3O4, emphasizing its potential in hyperthermia and its role as a dual-action chemotherapeutic carrier [65, 66]. Comparisons reveal that dextran-stabilized systems frequently exhibit higher stealth characteristics in blood-based assays, whereas chitosan formulations demonstrate stronger cellular internalization. Nonetheless, many investigations use limited in vitro experiments or small-scale animal studies, so the generalizability of robust internalization or hyperthermic outcomes to complex human tumors remains uncertain. Furthermore, specialized clinical equipment may be required for approaches involving strong external magnetic fields or hyperthermic conditions, underscoring the need for continued research on scalability and safety.

Other PSCs including cyclodextrins and CMC, have likewise demonstrated potential to enhance metal-based probes for GBM theranostics. One example employed gold-iron oxide nanohybrids coated with β-cyclodextrin-chitosan polymers for siRNA or miRNA loading, enabling combined optical and magnetic imaging, along with gene-silencing properties. This platform supported fluorescence and MRI-based molecular imaging and showed the capacity to bypass physiological barriers via intranasal delivery. Another approach used cyclodextrin-bearing IONPs conjugated to CTX, reporting improved efficacy against drug-resistant GBM cells and stable dispersion under physiological conditions [67]. These findings highlight cyclodextrins' usefulness in entrapping hydrophobic payloads or enabling host-guest interactions, potentially broadening the range of anticancer agents that can reach the brain.

CMC has been used to cap and functionalize QDs or to dope iron oxide NPs with chemotherapeutic agents [68]. Attaching CMC to ZnS or AgInS2 cores yields nanocrystals with a stable, water-dispersed shell and robust fluorescence, allowing cell labeling and monitoring in glioma models. Similar systems that conjugate DXR to carboxymethylated PSC shells exhibit pH-sensitive drug release, promoting payload release in the acidic tumor environment [69]. Though promising, concerns remain regarding toxic byproducts released during quantum dot or cyclodextrin-based NP degradation, warranting rigorous in vivo toxicity assessments. Ensuring safe accumulation patterns and reliable therapeutic outcomes in more advanced models remains critical before clinical translation.

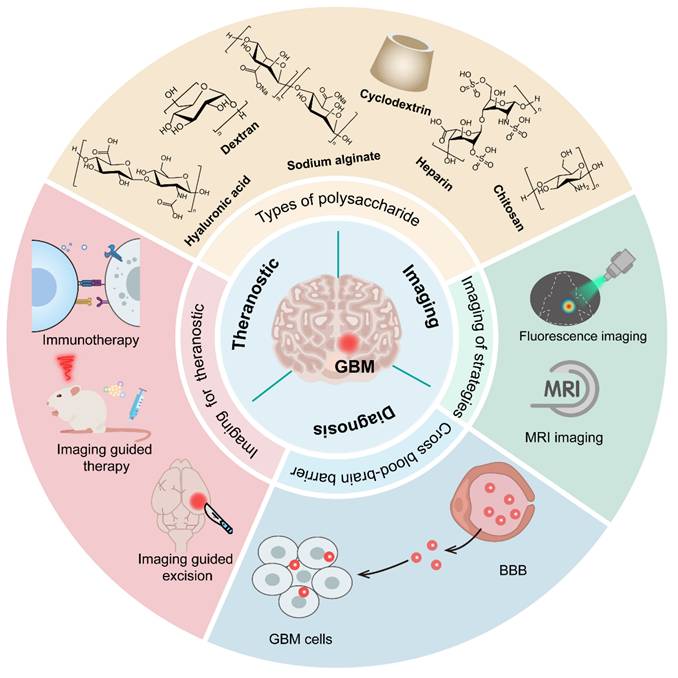

Schematic illustration of the generation and therapeutic application of TRAIL-engineered human mesenchymal stem cells (TRAILhMSCs) for glioma therapy. (A) hMSCs are modified via magnetofection. This process utilizes a magnetic nanoparticle complex consisting of SPIONs, HA, polyplex and plasmid DNA encoding for TRAIL, along with a magnetofection agent (MTN). (B) The resulting TRAILhMSCs are engineered for enhanced tumor tropism and MRI traceability. (C) Following intracranial injection into glioma-bearing mice, TRAILhMSCs migrate towards glioma. The expressed TRAIL protein on the surface of the hMSCs induces apoptosis in glioma cells, leading to tumor regression, while the SPIONs allow for non-invasive tracking of the cells via MRI. Adapted with permission from reference [63]. Copyright 2019 Ivyspring International Publisher (open access).

Less common but still compelling PSCs such as tragacanth and PST001 have also been investigated for metal NP stabilization in GBM applications. One study employed tragacanth to synthesize NiO nanosheets (18-43 nm), which displayed moderate photocatalytic dye degradation (60-82%) and cytotoxic effects against U87MG cells at higher concentrations, with an IC50 of 125 µg/mL [70]. These nanosheets exhibited favorable crystallinity and surface properties, suggesting potential for concurrent imaging based on NiO's optical characteristics, though direct MRI evidence remains limited. Another group developed DXR-loaded carboxymethylated PST001-coated iron oxide NPs that showed improved biocompatibility, enhanced intracellular uptake, and significant reactive oxygen species generation in both two-dimensional and 3D culture models [71]. While these materials demonstrate innovative surface chemistries and promise for GBM therapy, their ability to cross the BBB or deliver clinically meaningful theranostic performance requires further large-scale in vivo testing [72].

Collectively, enlisting these diverse PSCs to coat iron oxide or other metal NPs has enabled significant advancements in imaging contrast, tumor selectivity, and drug delivery. HA-MSA2 systems stand out for their CD44-mediated uptake and strong MRI signals, while chitosan offers higher uptake efficiency through electrostatic interactions, and dextran coatings generally improve circulation time. CD and CMC-based platforms broaden the scope of loaded therapeutics and imaging modalities, although attention to potential toxic byproducts remains paramount. Less common PSCs contribute distinctive surface chemistries but still need substantial in vivo validation to confirm their translational potential. Ongoing efforts must address biodistribution, immunogenicity, and scalability, ensuring that these PSC-based nanosystems can offer safe and effective theranostic solutions for GBM in clinical practice [73].

3.2 PSC-Based Probes for Optical (Fluorescence and Near-Infrared) Imaging

BAA-HA-MSA2-MSA2 remains a promising targeting ligand for GBM therapy, particularly when combined with NIR imaging for enhanced tumor visualization. A multifunctional nanocomplex exemplifying this role integrates B NSs and Au NPs with Ag2S, then caps the construct with BAA-BAA-HA-MSA2-MSA2 [74]. The system leverages the NIR-II fluorescence from Ag2S to enable deep-tumor imaging, while photothermal and sonodynamic activities bolster tumor ablation. The HA coating facilitates tumor-specific accumulation, and US-assisted microbubble disruption transiently opens the BBB, improving localization in GBM tissue. Although researchers observed robust anti-tumor immune responses and immunogenic cell death, the limited number of in vivo subjects constrains broader clinical extrapolation. Nonetheless, integrating HA with NIR-based approaches offers an encouraging direction for tumor-targeted imaging and therapy with greater spatiotemporal precision.

CMC is a versatile PSC matrix that can incorporate QDs for fluorescence-based imaging in GBM cells. For instance, cationic ε-poly-l-lysine-based ZnS QDs assemble with anionic CMC-encapsulated magnetite nanozymes via electrostatic interactions, forming hybrid organic-inorganic stimuli-responsive nanoplexes [75]. Unlike the purely diagnostic QDs discussed previously, these nanoplexes represent a dual-function theranostic platform: the QDs provide bright luminescence for tracking, while the magnetite nanozymes enable concurrent chemodynamic therapy. The QDs provide bright luminescence for imaging in both two-dimensional and 3D spheroid models, while the magnetite nanozymes enable chemodynamic therapy and magnetohyperthermia. Another approach involves supramolecular QD-biopolymer-drug assemblies, where ZnS QDs capped with CMC are conjugated with DXR, facilitating simultaneous bioimaging and chemotherapy. A parallel strategy uses CMC functionalized with cell-penetrating and pro-apoptotic peptides to complex fluorescent AIS semiconductor nanocrystals, resulting in multimodal imaging and potent cytotoxic effects against GBM cells [76]. Although these studies converge on the capacity of CMC to stabilize QDs, NP size and luminescence intensity vary due to differences in QD core composition and the inclusion of therapeutic moieties. A key limitation arises from predominantly in vitro protocols, which may not capture in vivo pharmacokinetics or fully represent the tumor microenvironment. Nonetheless, these findings collectively highlight the potential of CMC-based fluorescent nanoplatforms to advance theranostic applications in GBM.

Dextran, a commonly used PSC for NP coating, enhances the stability, biocompatibility, and imaging capabilities of IONPs. One dextran-based nanosystem featured crosslinked iron oxide cores labeled with Cy5.5 for dual-modal MRI and optical imaging. Its 25 nm cores and crosslinked shell allowed preferential accumulation in orthotopic GBM following intravenous injection, while concurrently delivering antisense oligonucleotides against oncogenic miRNA. Although variability in dextran thickness and crosslinking density can influence biodistribution and clearance, this platform demonstrated transvascular passage and consistent imaging signals in glioma-bearing models. Optimizing coating strategies or further tailoring the shell could improve targeting accuracy while preserving robust imaging contrast.

Chitosan, another abundant PSC, can be adapted for tumor-targeted drug delivery and fluorescence-based imaging. One example employs selenium-Chitosan NPs loaded with TMZ, coated with Eudragit® RS100 polymer, and tracked through encapsulated curcumin [77]. The innate fluorescence of curcumin confirms NP uptake by glioma cells, and Chitosan-based carriers lower the IC50 while downregulating TMZ resistance genes. However, curcumin's photobleaching limits extended imaging capability. Still, combining Chitosan-mediated tumor targeting with fluorescent labeling offers a promising method for monitoring drug release and therapeutic efficacy in GBM [78].

Collectively, PSC-based vehicles composed of HA, CMC, dextran, or chitosan present complementary strategies for coupling robust imaging with tumor-directed therapies in GBM. By incorporating fluorescent or NIR markers, each system enables real-time tumor visualization, more accurate drug delivery, and enhanced assessment of therapeutic effectiveness [79]. Although preclinical studies underscore their promise, variations in particle composition and the complexity of the BBB remain key challenges. Standardizing imaging parameters, addressing scale-up, and evaluating long-term safety are essential next steps in translating these platforms to clinical settings. Continued research may ultimately yield safe, effective, and clinically feasible PSC-based nanotechnologies for targeted GBM therapy.

4. PSC-Based Systems for GBM Therapy

PSCs are increasingly employed to deliver chemotherapeutic drugs and genetic materials to GBM cells, owing to their biocompatibility, biodegradability, and adaptable chemical structures. These properties support the development of nanocarriers that address critical GBM challenges, including the BBB, tumor heterogeneity, and drug resistance. By modulating parameters such as molecular weight, substitution degree, and surface properties, PSC nanocarriers achieve enhanced stability, targeted delivery, and prolonged circulation, thereby improving the therapeutic index. Their utility spans a wide range of payloads, from conventional anticancer drugs to gene-based treatments, all while mitigating off-target effects. Furthermore, conjugations with PEG or targeting ligands augment immune evasion and strengthen site-specific accumulation. Recent studies have explored various PSC platforms, capitalizing on stimuli-responsive linkers to enable controlled release within the tumor microenvironment. Through these design strategies, PSC-based platforms show promise in addressing GBM's complex pathology and improving patient outcomes.

4.1 Chitosan-based approaches

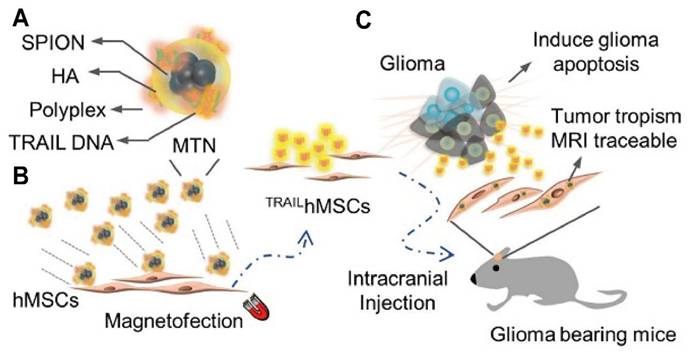

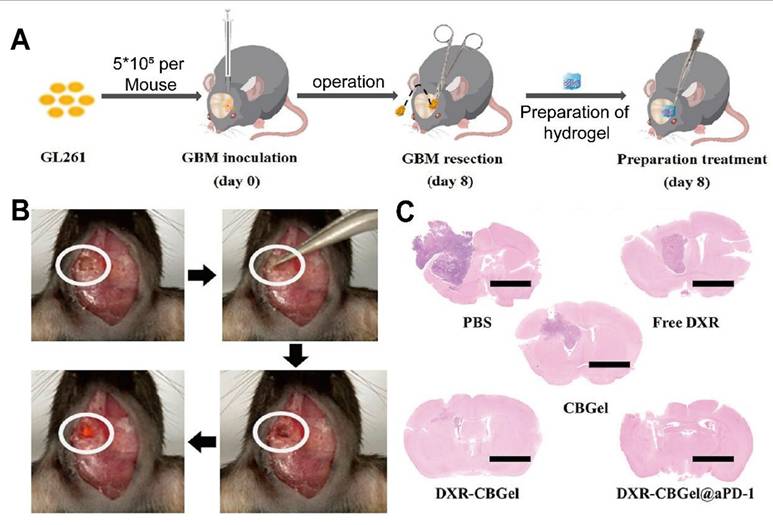

Chitosan-based nanocarriers have garnered attention for intranasal and systemic delivery (Table 2) [80]. For example, nanocapsules utilizing chitosan's mucoadhesive properties significantly reduced glioma size in mouse models (Figure 3A, B) [81]. Other approaches involve thermosensitive hydrogels loaded with drugs like docetaxel (DTX) (Figure 3C), which demonstrated significant inhibition of glioma growth in preclinical models (Figure 3D) [82]. Additionally, drug delivery systems using chitosan have been developed for post-surgical local treatment to prevent glioma recurrence (Figure 4A). In such studies, the drug delivery system is implanted into the tumor remnant cavity after resection (Figure 4B), showing significant inhibition of subsequent tumor growth in an animal model (Figure 4C) [83]. Beyond small molecule agents, chitosan-based systems can also preserve the biological activity of macromolecules. One study demonstrated that trimethyl chitosan (TMC) NPs encapsulating an IGF-1R inhibitor (IGF-Trap) yielded superior intracerebral drug uptake and prolonged survival in mouse glioma models [84].

Additional research underscores the versatility of chitosan-based carriers in accommodating multiple functional elements. Magnetic graphene oxide modified with chitosan and conjugated to gastrin-releasing peptide allowed dual magnetic and receptor-mediated DXR targeting. This system achieved pH-responsive release, significantly lowering the IC50 in GBM cells [27]. Another platform combined silicon NP with a chitosan coating, extending circulation time in tumor-bearing mice and favoring intratumoral accumulation through the EPR effect [85]. Chitosan-coated iron oxide NP similarly demonstrated reduced cytotoxicity in C6 glioma cells compared to uncoated variants, implying that the polymeric layers can mitigate metal-associated toxicity while bolstering anticancer efficacy [86]. Moreover, surface alterations such as chemical modifications to chitosan can improve its solubility at physiological pH. Trimethyl chitosan (TMC), for example, has garnered special interest for its ease of functionalization, enabling ligand attachment that bolsters targeting efficiency and overall therapeutic potential.

Studies have highlighted TMC-based carriers co-functionalized with ligands such as RGD or folate, which anchor selectively to overexpressed receptors in GBM [87]. One investigation described a TMC NP platform functionalized with RGD and L-arginine that directed cytotoxic activity primarily toward cancer cells in a preclinical model, sparing healthy tissues and underlining the specificity conferred by these ligands. Another effort demonstrated folic-acid-conjugated chitosan NP, resulted in improved mucoadhesion and cytotoxic activity in vitro [88]. Additionally, chitosan has been derivatized via N-alkylation to form micelle-like structures, facilitating translocation of macromolecular payloads across the BBB [89].

Chitosan-Based Approaches

| Approach/Method Name | Carrier System | Payload/Active Agent | Targeting/Delivery Strategy | Key Finding/Performance Metric | Validation Model | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTX-Chitosan-HPMCP NPs | Chitosan-HPMCP NPs | Methotrexate (MTX) | P-gp efflux inhibition; Mucoadhesion | Enhanced cytotoxicity (IC50 = 68.79 vs 80.54 µg/mL for free MTX) | U251MG GBM cells | Naves et al. [84] |

| iNSC-laden Injectable Chitosan Hydrogel | Injectable thermo-responsive hydrogel | Induced neural stem cells (iNSCs) | Post-surgical local cell delivery | 50% increase in median survival vs iNSCs alone | Post-surgical GBM mouse model | King et al. [97] |

| Magnetic GO/Chitosan/Iron Oxide Microspheres | Graphene oxide/chitosan/iron oxide microspheres | Temozolomide (TMZ) | Magnetic field- and pH-sensitive release | Drug release doubled in 90 min with 100 Hz magnetic field | GBM cells (MTT assay) | Ahmadi et al. [16] |

| AT101-conjugated Chitosan Nanobubbles | Chitosan nanobubbles (NBs) | Delivery platform (unloaded) | GPC1 protein targeting via AT101 antibody | Increased specific tumor delivery compared to unconjugated NBs (p=0.02) | U-87 MG xenograft model | Cintio et al. [93] |

| Macroporous Alginate-Chitosan Hydrogel | Macroporous alginate-chitosan hydrogel | Cell trap (no drug) | Physical trapping of GBM cells for subsequent radiotherapy | F98 GBM cells accumulate and are retained within the gel matrix | F98 GBM cells | Parès et al. [99] |

| TPP-conjugated Chitosan NPs | Triphenylphosphonium (TPP+)-conjugated chitosan NPs | Temozolomide (TMZ) | Mitochondrial targeting via TPP+; Intranasal delivery | Entrapment efficiency of 93.59%; Greater nasal mucosal retention | Goat nasal mucosa (ex vivo); In vitro cell lines | Dahifale et al. [91] |

| Chemo-Immunotherapy Crosslinked Hydrogel | Pluronic F-127/Chitosan thermo-responsive hydrogel | Doxorubicin (DOX), BMS-1 | Intratumoral injection for synergistic chemo-immunotherapy | Tumor 43 times smaller than untreated group | GBM tumor-bearing mouse model | Chuang et al. [191] |

| Etoposide-loaded Chitosomes | Chitosomes (chitosan-coated liposomes) | Etoposide | Parenteral administration; Enhanced stability | Heightened efficacy against the U373 GBM cell line | U373 cell line | Gonzalo et al. [85] |

| CRT-functionalized Chitosan/HA Nano-emulsion | Chitosan/hyaluronic acid layered nano-emulsion | Paclitaxel | CRT peptide targeting of transferrin receptor on BBB | 41.5% higher uptake in brain endothelium cells than negative control | bEnd.3 cells (BBB model) | Capua et al. [94] |

| DOX-loaded LLPs in Chitosan/HA/PEI Hydrogel | Liposome-like particles in Chitosan/HA/PEI hydrogel | Doxorubicin (DOX) | Controlled local delivery in resection cavity | Sustained drug release up to 148 hours | GBM spheroids; In vitro cell studies | Adiguzel et al. [98] |

| Gemcitabine Chitosan-coated PLGA NPs | Chitosan-coated PLGA NPs | Gemcitabine (GEM) | Intranasal delivery; Mucoadhesion | Promoted GEM antiproliferative activity and sensitized cells to TMZ | U215 and T98G human GBM cell lines | Ramalho et al. [103] |

| GRP-conjugated Magnetic Graphene Oxide | Chitosan-coated magnetic graphene oxide (mGOC) | Doxorubicin (DOX) | Dual active (GRP peptide) and magnetic targeting | Best potency to suppress tumor growth and prolong animal survival | Orthotopic U87 brain tumor model in mice | Dash et al. [27] |

| DXR-loaded Self-crosslinked Hydrogel (DXR-CBGel) | BSA NPs self-crosslinked with chitosan | Doxorubicin (DXR), anti-PD-1 antibody | Localized chemoimmunotherapy as an in situ vaccine | Effectively inhibited cancer recurrence post-surgery | GBM lesions (animal model) | Long et al. [83] |

| Review of Polymeric NPs for GBM | Chitosan, PLGA, PEG, etc. NPs | Various chemotherapeutics | Active targeting with ligands (transferrin, chlorotoxin, etc.) | Review article summarizing multiple strategies | N/A (Review) | Paula et al. [92] |

| 3D Chitosan-Hyaluronic Acid Scaffolds | Chitosan-hyaluronic acid (CHA) porous scaffold | 3D tumor model (no drug) | High-throughput screening (HTS) platform | Produced uniform response (CV < 0.15) and wide screening window (Z' > 0.5) | Three human GBM cell lines | Zhou et al. [108] |

| Curcumin-Chitosan Nano-complex | Curcumin-chitosan nano-complex | Curcumin | Epigenetic modification via gene expression regulation | Significantly increased MEG3 and decreased DNMT gene expression | GBM cell line | Abolfathi et al. [106] |

| Chitosan-functionalized Silicon NPs | Chitosan-coated Silicon NPs (SiNPs) | Silicon NPs (photosensitizer) | Passive targeting via Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect | Tumor accumulation increased to 39.55% after 7 days | Nude mice with subcutaneous human GBM | Baati et al. [88] |

| Sialic Acid-functionalized Selenium NPs@Chitosan | Sialic acid-coated, chitosan-stabilized Se NPs | Selenium NPs (Se NPs) | Surface modification with sialic acid for improved stability/activity | Dose- and time-dependent inhibitory effects on T98 GBM cells | T98 and A172 GBM cell lines | Abadi et al. [95] |

| TMZ-loaded Chitosan-based Thermogels | Chitosan-β-glycerophosphate thermogel with SiO2/PCL microparticles | Temozolomide (TMZ) | Local delivery into post-resection cavity | Caused a significant reduction in the growth of tumor recurrences | GBM resection and recurrence mouse model | Gherardini et al. [109] |

In parallel, chitosan's utility extends to functionalization strategies that target specific receptors or enable unique trans-barrier transport. Anti-glypican-1 antibody (AT101)-conjugated chitosan nanobubbles selectively accumulated in glypican-1-overexpressing GBM in a mouse model, significantly augmenting tumor binding relative to unmodified counterparts [90]. Triphenylphosphonium (TPP⁺)-conjugated chitosan formulations likewise improved mitochondrial targeting in GBM cells, thereby enhancing the cytotoxic effectiveness of TMZ. A consecutive layering of chitosan and HA in nano-emulsions, further functionalized with a CRT peptide, yielded increased uptake across BBB-cell models by exploiting transferrin receptor binding [91]. Explorations of sialic-acid-covered chitosan NPs add another dimension by taking advantage of sialic acid's tumor-targeting capabilities and stabilizing effects.

Study of Chitosan in the treatment of glioma. (A) Nanocapsules coated with Chitosan and loaded with simvastatin are administered intranasally to avoid the BBB and improve drug delivery efficiency. (B) After 14 days of treatment, gliomas in the experimental group were significantly smaller than those in the control group. (C) The thermosensitive hydrogel was prepared with PF127 and N,N, N-TMC as raw materials and loaded with DTX for GBM. (D) PF127-TMC/DTX gel with high concentration can significantly inhibit the growth of glioma cells in vitro. Adapted with permission from reference [81, 82]. Copyright 2022 Elsevier B.V. and 2018 Elsevier Ltd., respectively.

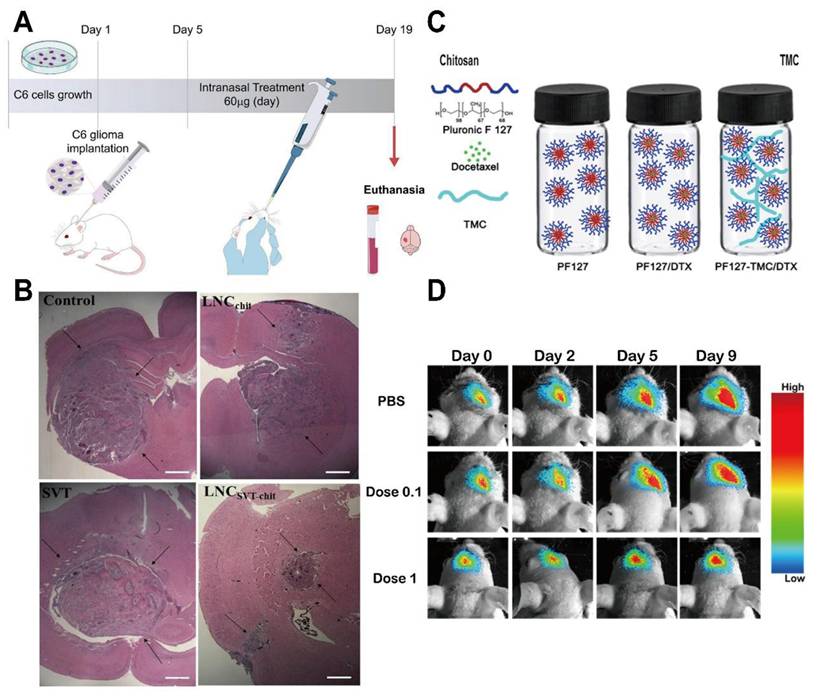

Beyond nano-scale delivery, chitosan-based hydrogels facilitate localized and sustained drug release, particularly beneficial following glioma resection [92]. In situ gelation triggered by temperature changes or crosslinking can achieve prolonged retention of therapeutic agents at the tumor site. One example involved an injectable chitosan hydrogel loaded with tumoricidal neural stem cells (iNSCs), resulting in long-term survival benefits and increased median survival in animal studies relative to direct stem cell injections [93]. Another formulation employed DXR-loaded liposome-like particles (LLP-DOX) in a chitosan/hyaluronic acid/polyethyleneimine (CHI/HA/PEI) matrix, providing gradual drug release and substantially reducing the viability of three-dimensional (3D) GBM spheroids [94]. A further approach used a dual-crosslinked macroporous hydrogel composed of sodium alginate and chitosan, which effectively sequestered GBM cells post-resection in an animal model without overwhelming healthy tissues [95]. Additionally, an albumin-based hydrogel crosslinked with chitosan extended intratumoral retention of Dox in a mouse model, leading to immunogenic cell death and minimal systemic toxicity [96]. Although these matrices require precise tuning of mechanical properties and may rely on suitably sized resection cavities, they offer a promising route to contain residual glioma cells and reduce the risk of recurrence.

Intracavity-filled Chitosan system significantly suppressed tumor recurrence. (A) Study of DOX-loaded bovine serum albumin NPs and chitosan self-crosslinking drug delivery system in glioma recurrence after surgery. (B) Tumor resection was performed on the 8th day after tumor inoculation, and drug delivery systems of different groups were implanted in the tumor remnant cavity. (C) H&E staining on the 18th day of each group showed that the experimental group had significant inhibition on tumor growth after glioma surgery. Adapted with permission from reference [83]. Copyright 2023 American Chemical Society.

Multi-modal or stimuli-responsive chitosan formulations further broaden therapeutic options by merging magnetic, photothermal, or pH-sensitive functionalities. One pH- and magnetically responsive system incorporated iron oxide NPs into a chitosan-graphene oxide matrix, delivering TMZ under external magnetic field stimulation and accelerating drug release within acidic tumor environments [97]. This system functions as a true theranostic platform: the iron oxide core enables T2-weighted MRI tracking of tumor accumulation, while the chitosan shell concurrently manages the stimuli-responsive release of the chemotherapeutic payload. Others employed NIR photothermal conversion using platinum-gold nanorods layered in a chitosan/polycaprolactone scaffold, which yielded extended TMZ release and a high cell-killing rate in GBM cultures under NIR irradiation [98, 99]. In another approach, radiofrequency-triggered hyperthermia in chitosan-coated silicon NPs intensified tumor cell death in preclinical tests. Chitosan is also conducive to photodynamic therapy, exemplified by berberine-based chitosan nanosystems that induced apoptosis in T98G cells while sparing healthy astrocytes [100]. Successful integration of these stimuli hinges on precise field delivery and minimal off-target damage, yet the adaptive nature of chitosan indicates that such hurdles may be overcome with design refinements and advanced instrumentation.

Combining therapeutic modalities appears increasingly feasible with chitosan carriers, which can integrate several agents or strategies in a single platform. For instance, chitosan NPs loaded with gemcitabine heightened the susceptibility of glioma cells to TMZ, achieving synergistic apoptotic effects [101, 102]. Dual photothermal-chemotherapeutic regimens have also been devised. For example, HA-modified chitosan-lipid NPs co-loaded with cisplatin and iron oxide, were guided externally to glioma tissue and activated by NIR light to enhance cytotoxic potency in vivo [103]. Curcumin-chitosan nanocomplexes further exemplify the potential for epigenetic reprogramming, as they modulated DNA methyltransferase gene expression and displayed robust dose- and time-dependent cytotoxicity in GBM cells [104]. While precise attribution of efficacy to each individual component remains challenging, these multi-pronged systems generally yield greater tumoricidal effects than single-agent regimens.

Collectively, these diverse approaches illustrate chitosan's broad applicability to GBM therapy, ranging from NP constructs and hydrogels to complex multi-modal regimens [105]. Three-dimensional tumor models employing chitosan-HA scaffolds emphasize the polymer's promise for both drug delivery and high-throughput drug screening, as the scaffold's pore size modulates GBM cell behavior and resistance [106]. Simultaneously, stealthy chitosan-capped silicon NPs capable of extended circulation underscore emerging strategies to prolong half-life and enhance tumor accumulation [107]. Despite these encouraging findings, many studies rely on limited preclinical models, do not include standard comparators, or assess only short-term outcomes. Moving forward, comprehensive validation in intracranial models, standardized efficacy metrics, and large-scale manufacturing protocols will be vital for translating chitosan-based nanomedicines into effective clinical solutions against GBM.

4.2 HA-based approaches

HA has emerged as a promising PSC-based platform for targeting GBM due to its intrinsic tumor-homing capabilities [108]. By selectively binding these receptors, HA-based carriers facilitate the uptake of chemotherapeutics within tumor tissues while minimizing off-target effects [109]. Moreover, HA's natural biocompatibility, biodegradability, and relatively low immunogenicity support its application in NP formulations for efficient and well-tolerated drug delivery. Preclinical studies show that HA-based nanocarriers accumulate in GBM cells and exploit local microenvironmental conditions to enable targeted release, ultimately improving intracranial drug distribution. Taken together, these advances underscore HA's potential to serve as a versatile vehicle that can cross the BBB and enhance therapeutic specificity (Table 3).

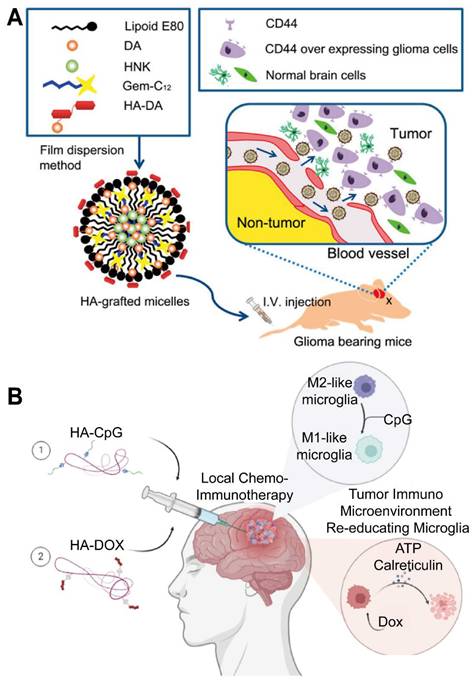

Numerous investigations use HA to functionalize NPs for enhanced drug delivery and imaging. For example, HA-modified copolymers are recognized by CD44 receptors on glioma cells. This interaction leads to cellular uptake in vitro through mediated endocytosis, as depicted in Figure 5A [110]. Once at the target, HA-drug conjugates can also improve the local efficacy of chemotherapy and immunotherapy [111]. To circumvent the BBB, other approaches in animal models show that nasally administered HA-modified nanomicelles can be rapidly transported to the brainstem via the trigeminal pathway, achieving efficient delivery to gliomas (Figure 5B) [112]. Several reports describe magnetic or metallic NP cores coated with HA to achieve tumor selectivity, stability, and biocompatibility. For instance, one study established superparamagnetic iron oxide NPs (SPIONs) stabilized with an HA coating, which provided excellent colloidal stability, improved biocompatibility, robust GBM cell uptake, in vitro, and T2 contrast potential for MRI [62, 89].

HA-modified lipid-based systems have also shown promise in GBM therapy by encapsulating or conjugating various payloads. One investigation encapsulated Dox in HA-liposomes to target CD44-overexpressing GBM cells, revealing a marked increase in tumor growth inhibition in an animal model relative to free Dox [113]. However, comparative evaluations of HA-systems reveal a "binding site barrier" phenomenon. High-affinity HA nanocarriers often bind irreversibly to CD44 receptors at the tumor periphery, effectively preventing penetration into the hypoxic, necrotic core where resistant stem cells reside. This suggests that while HA enhances tumor accumulation, simply maximizing receptor affinity may be counterproductive; optimizing ligand density to allow for detachment and deeper diffusion is likely required for superior efficacy (Figure 6) [114].

Hyaluronic Acid-Based Approaches

| Approach/Method Name | HA-based Core Structure | Therapeutic/Diagnostic Payload | Mechanism/Function | Additional Targeting Moiety | Validation Model | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HA-SPION Dual-Targeted System | Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticle (SPION) | SPION (MRI contrast) | Dual-targeted diagnosis and therapy | Folic acid | Glioma/adenocarcinoma cells (in vitro) | Kasprzyk et al. [62] |

| CHI/HA/PEI Hydrogel with LLP-DOX | Hydrogel (Chitosan/HA/PEI) | Doxorubicin in liposomes | Local, controlled drug release | N/A (local delivery) | GBM spheroids (3D in vitro) | Adiguzel et al. [98] |

| IR780-rGO-HA/DOX Nanoplatform | Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) | Doxorubicin; IR780 (photosensitizer) | Multimodal therapy (Chemo/PTT/PDT) | N/A | U87 cells; Xenograft tumor model (in vivo) | Dash et al. [111] |

| ICOVIR17-MSC in sECM | Synthetic ECM (targets endogenous HA) | Oncolytic virus expressing hyaluronidase | Oncolytic virotherapy; ECM degradation | N/A | GBM resection mouse model; PDX xenografts | Martinez et al. [119] |

| RGD-Functionalized HA 3D Scaffold | Biomaterial scaffold | N/A (model system) | 3D in vitro model for studying chemoresistance | RGD peptide (Integrin targeting) | Patient-derived GBM cells | Xiao et al. [118] |

HA-based NPs improve the integration of glioma diagnosis and treatment. (A) HA-modified copolymers are recognized by CD44, which is overexpressed on glioma cells, and are taken up through CD44-mediated endocytosis. (B) HA-modified nanomicelles can be administered nasally and rapidly transported to the pontine through the trigeminal pathway, avoiding the BBB and achieving efficient delivery of gliomas. Adapted with permission from reference [110, 112]. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society and 2021 Elsevier B.V., respectively.

Schematic illustration of hyaluronan-enveloped peptide nanomicelles for the treatment of glioma. HA-drug conjugate can improve the efficacy of local chemotherapy and immunotherapy for glioma. Adapted with permission from reference [114]. Copyright 2023 Elsevier Ltd.

Genetic material delivery via HA coatings further illustrates the scope of these nanotechnologies. HA-grafted lipid NPs were reported to deliver siRNA against Polo-Like Kinase 1, achieving over 80% gene knockdown and significantly prolonged survival in an orthotopic GBM model [114]. One group developed HA-lipid NP systems designed to deliver RNA interference (RNAi) constructs directly to GBM cells in culture, achieving favorable uptake and silencing efficiency. Another study used a similar HA-lipid platform to deliver miR-181a, prolonging survival in an in vivo tumor model by enhancing accumulation in GBM tissue [115]. Overall, HA-functionalized NPs show considerable promise for improving diagnostic accuracy, therapeutic efficacy, and multimodal approaches in GBM management, though further validation is necessary to confirm their in vivo stability and safety.

Efforts have also focused on HA-based hydrogels designed to provide localized therapy. Injectable or implantable hydrogel composites formed from HA and other polymers offer sustained drug release in situ, aligning mechanical properties with those of brain tissue and improving intracranial drug retention. One group demonstrated CHI/HA/PEI hydrogels that entrapped LLP-DOX, slowing drug release in vitro over 148 hours while preserving low genotoxicity [69]. Another investigation employed a cucumber uril-crosslinked HA hydrogel with 98% water content, facilitating straightforward placement within resection cavities in a preclinical surgical model and enabling therapeutic antibody delivery [116].

Beyond drug delivery, HA-rich scaffolds are employed to investigate cellular behaviors, including GBM invasion, chemoresistance, and proliferation, in physiologically relevant 3D microenvironments. One report systematically varied HA concentration in a soft matrix and identified in a 3D culture system a biphasic effect on patient-derived GBM invasion, with specific HA thresholds maximizing invasive capacity [117]. Parallel findings demonstrated that CD44 binding via HA, together with integrin interactions, can augment resistance to alkylating agents, more accurately mimicking in vivo response patterns than conventional sphere cultures [118]. Despite the promise of these biomimetic approaches, patient-specific variability in HA-driven invasion emphasizes the need for tailored matrix formulations that capture disease heterogeneity while supporting reproducible screening.

Alternate strategies seek to deplete or remodel HA within the tumor microenvironment instead of incorporating it as a scaffold or coating. One study employed an oncolytic adenovirus encoding soluble hyaluronidase, demonstrating in an animal model that localized HA degradation improved viral dispersion and reduced glioma burden [119]. This strategy stands in contrast to formulations that exploit intact HA-CD44 interactions but presents a complementary avenue to counteract the dense ECM barriers limiting drug and gene vector penetration.

Collectively, these findings establish HA as a multifaceted component in the development of next-generation GBM therapies. HA-based NPs leverage CD44 receptor binding to improve drug uptake, provide MRI contrast, and enable synergistic treatments combining photothermal or photodynamic approaches. HA-centered hydrogels and 3D scaffolds can serve as controlled drug depots and physiologically relevant disease models, facilitating localized therapy and elucidating tumor-ECM interactions. In parallel, strategies that degrade HA in the tumor microenvironment attempt to disrupt physical and molecular barriers to treatment, offering a distinct route for enhancing drug penetration. By capitalizing on HA's unique capacity to bind CD44, mimic native ECM, and modulate therapeutic delivery, PSC-based nanomedicines stand poised to expand the therapeutic landscape for GBM [120, 121].

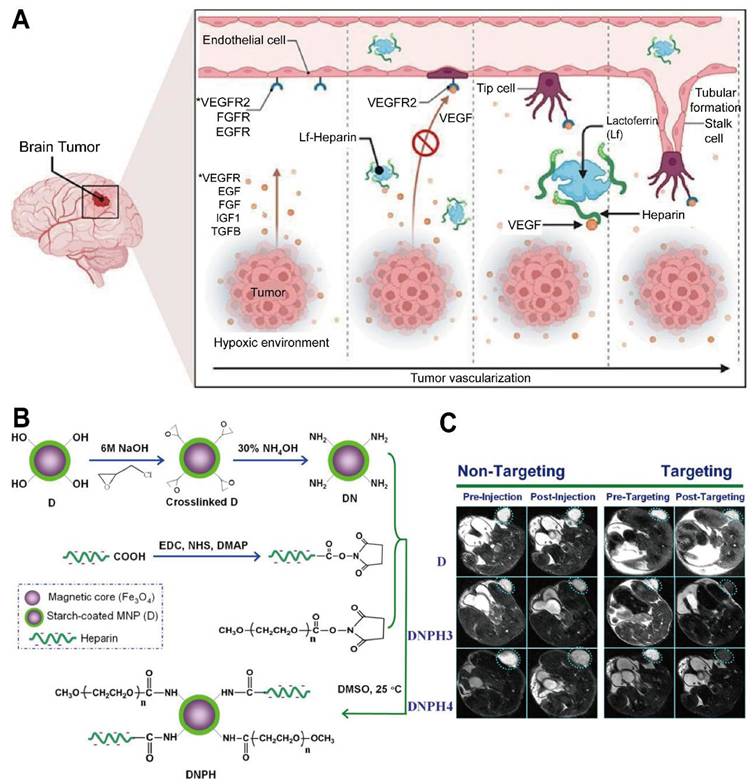

4.3 Dextran-based approaches

Dextran, a PSC composed predominantly of α-1,6-glycosidic bonds, has received growing attention in GBM therapy due to its ease of chemical modification (Table 4). Its backbone carries multiple hydroxyl groups that enable flexible conjugation to drugs, antibodies, or targeting molecules, thereby tailoring dextran-based nanosystems for specific therapeutic interventions [122, 123]. Such modifications can lessen unwanted plasma protein interactions, prolonging circulation times that heighten drug delivery. The polymer's customizable surfaces help NP evade opsonization and clearance, thus providing sufficient time for transport across the BBB or blood-tumor barrier (BTB) [124, 125]. This extended presence elevates drug residence in the bloodstream and subsequent tumor accumulation, particularly where hydrophilic surfaces and versatile chemical derivatization reduce reticuloendothelial uptake [126]. By finely tuning NP size and surface properties, these systems can traverse biological barriers selectively, concentrating anticancer agents at the desired site [127, 128]. Dextran can be equipped with redox- or pH-sensitive linkers to target intracellular drug release in tumor cells, exploiting high GSH levels or acidic compartments for enhanced specificity [125].

Dextran-Based Approaches

| Approach/Method Name | Dextran Formulation | Payload/Active Agent | Primary Function | Validation Model(s) | Key Innovation | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dextran Sulfate/LMWP NPs | Ionic complex of dextran sulfate and low molecular weight protamine | Nucleic acids | Non-viral gene delivery | GBM cell lines, 3D spheroids, zebrafish models | Cationic polymeric NPs for gene delivery with negligible toxicity and efficient internalization | Esteban et al. [130] |

| Dexamethasone-loaded dex-HEMA Hydrogel | Dextran-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (dex-HEMA) hydrogel | Dexamethasone (micelles) & dexamethasone phosphate (liposomes) | Localized, prolonged anti-edema drug delivery | In vitro release kinetics studies | Biphasic and sequential drug release from an immobilized dual-nanoparticle hydrogel system | Straten et al. [133] |

| Dextran-Coated Iron Oxide NPs (MN-anti-miR10b) | Crosslinked dextran coating on iron oxide NPs | Antisense oligonucleotide (anti-miR10b), Cy5.5 dye | Image-guided RNA delivery | Orthotopic GBM mouse model | Dual-modal (MRI/optical) tracking of a nano-platform delivering RNAi payload across the BBB | Kim et al. [26] |

| PD0721-DOX Antibody-Drug Conjugate | Dextran T-10 as a linker for conjugation | Doxorubicin (DOX) | Targeted chemotherapy (ADC) | EGFRvIII-positive and negative GBM cell lines | Dextran linker to create an scFv antibody-drug conjugate targeting EGFRvIII-expressing cells | Hu et al. [131] |

| Nano-realgar Hydrogel (NRA@DH Gel) | pH-sensitive dextran hydrogel with hyaluronic acid coating | Nano-realgar quantum dots (NRA QDs) | Synergistic chemo-radiotherapy | In situ GL261 GBM mouse model | Hydrogel acts as a sustainable ROS generator to deplete GSH and enhance radiotherapy efficacy | Wang et al. [135] |

| Biomimetic Dextran NPs | pH-sensitive dextran nanoparticle core | ABT-263 and A-1210477 (Bcl-2/Mcl-1 inhibitors) | Brain-targeted combination drug delivery | GBM cell lines, patient-derived cells, orthotopic GBM mouse model | Biomimetic (RBC membrane, ApoE peptide) coating for BBB penetration and synergistic drug delivery | He et al. [132] |

| Chitosan-Dextran SPIONs (CS-DX-SPIONs) | Hybrid chitosan-dextran coating on SPIONs | SPIONs (contrast agent) | MRI contrast enhancement & targeted delivery | Glioma cell lines, orthotopic C6 glioma rat model | Hybrid chitosan-dextran coating enhances cellular uptake and tumor retention for improved MRI contrast | Shevtsov et al. [66] |

| Acetalated Dextran (Ace-DEX) Fibrous Scaffolds | Acetalated dextran biodegradable fibrous implant | Paclitaxel and Everolimus | Interstitial combination chemotherapy | GBM cell lines, orthotopic GBM resection/recurrence mouse models | Synchronized interstitial release of synergistic drugs from scaffolds with tailored degradation rates | Graham-Gurysh et al. [136] |

| Tunable Acetalated Dextran (Ace-DEX) Scaffolds | Acetalated dextran nanofibrous scaffolds | Paclitaxel | Interstitial therapy with controlled release | Orthotopic GBM resection/recurrence and distant metastasis mouse models | Demonstrating that drug release rate is a critical parameter for efficacy in different tumor models | Graham-Gurysh et al. [137] |

Several groups have harnessed dextran in NP systems alongside other polymers or linkers to advance gene and drug therapy. One formulation hinged on ionic complexation of low molecular weight protamine (LMWP) and dextran sulfate to condense nucleic acids in GBM models [129]. These cationic NP demonstrated effective nucleic acid delivery in both two- and 3D cultures, as well as in zebrafish, but detailed validation against human intracranial complexities remains limited. Another dual-sensitive NP employed dendrimer-dextran conjugation via matrix metalloproteinase- and pH-responsive linkers to release DXR in situ [130]. While this approach improved NP retention and penetration in murine glioma, heterogeneous enzymatic activity could affect uniform disassembly in clinical settings.