13.3

Impact Factor

Theranostics 2026; 16(8):4076-4089. doi:10.7150/thno.123726 This issue Cite

Research Paper

A cochlea-sparing strategy for non-invasive control of intracranial schwannomas via peripheral irradiation and anti-PD-1 therapy enhanced by STING activation

1. Edwin L. Steele Laboratories, Department of Radiation Oncology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, 02114, USA.

2. Department of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery and Department of Neurosurgery, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, 94305, USA.

3. Biostatistics Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, 02114, USA.

4. Department of Radiation Oncology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, 02114, USA.

5. Department of Neurology and Cancer Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, 02114, USA.

* Z.Y., S.L. contributed equally to this work.

†Current address: Department of Radiation Oncology, Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital, National Clinical Research Center for Cancer, Tianjin Clinical Research for Cancer, Key Laboratory of Cancer Prevention and Therapy, Tianjin, 300060, China.

Received 2025-8-14; Accepted 2026-1-13; Published 2026-1-21

Abstract

Rationale: NF2-related schwannomatosis (NF2-SWN) is a progressive neurological disorder with a hallmark of bilateral vestibular schwannomas (VSs), leading to irreversible hearing loss and reduced quality of life. To date, the FDA has not approved any pharmacological therapies for treating VS or hearing loss. While radiotherapy (RT) is the standard treatment for growing VSs, it often exacerbates hearing loss. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have revolutionized cancer treatment; however, their efficacy in non-malignant tumors like VS remains largely unexamined.

Methods: We used immune-competent VS mouse models to assess the efficacy of combined anti-PD1 (αPD1) and RT treatment, tumor growth, and hearing preservation.

Results: We found three significant therapeutic benefits: i) RT induces immunogenic cell death and activates the STING pathway, enhancing αPD1 efficacy and generating long-term immune memory, ii) The combination strategy reduces the required RT dose necessary for effective tumor control, potentially minimizing RT injury to surrounding normal tissues, and iii) RT to peripheral nerve tumor induces a systemic abscopal effect, which enhances αPD-1 efficacy to effectively control intracranial schwannomas without direct irradiation, sparing the cochlea from radiation exposure and avoiding auditory radiation injury.

Conclusion: Our findings provide a compelling rationale for deploying ICIs in combination with radiotherapy as a novel treatment approach for patients with VS and NF2-SWN.

Introduction

NF2-related schwannomatosis (NF2-SWN) is a dominantly inherited neoplasia syndrome caused by germline mutation in the NF2 tumor suppressor gene. NF2-SWN occurs in approximately 1 in 61,000 individuals and exhibits an almost 100% penetrance [1, 2]. Patients with NF2-SWN develop multiple non-malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, and the pathognomonic hallmark is bilateral vestibular schwannomas (VSs). The continuous growth of VSs results in sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) and considerable morbidity, significantly impacting patients' quality of life [3]. In advanced cases, large VSs can compress the brainstem, resulting in severe morbidity and even death [4]. Standard treatments for growing VSs include surgery and radiotherapy (RT), however, both pose substantial risks, including irreversible hearing loss, persistent vestibular dysfunction, and cranial nerve impairment [5-7]. There is a critical need for targeted pharmacologic therapies to arrest VS progression and mitigate SNHL.

In patients with sporadic VS, tumor control after irradiation is excellent, with long-term tumor control rates of around 88-91%, but significantly lower for patients with NF2-SWN [8, 9]. In addition, radiotherapy can cause adverse effects, including: i) further hearing loss due to ototoxicity [8, 9], ii) pseudoprogression - a transient increase in tumor volume that occurs in 23-44% of VS patients and can worsen brainstem compression [10-12], and iii) increased risk of malignant transformation [13-15]. There is a need for a combination regimen that can lower the therapeutic dose of RT required for tumor control, and, consequently, reduce radiation-induced ototoxicity and adverse effects.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have revolutionized cancer therapy by enhancing the body's anti-tumor immune response. These agents, including monoclonal antibodies targeting programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1), its ligand PD-L1, and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), function by blocking immune inhibitory signals that suppress T cell activation. By restoring T cell effector functions, ICIs promote tumor cell elimination and have been associated with significant improvements in clinical outcomes across multiple malignancies [16, 17]. As a result, ICIs have received FDA approval to treat a broad spectrum of solid tumors, either as monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy and other therapeutic modalities [18].

VS harbor substantial infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [19]; however, a large fraction of these tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes express PD-1 [20], suggesting impaired immune function [21]. There is high expression of PD-1 ligand, B7-H1, in VS [19, 22], highlighting the potential role of immune checkpoint pathways in the tumor microenvironment. Despite these observations, few studies have explored the treatment potential of ICIs in VS. In a subcutaneous mouse model, an anti-PD1 (αPD1) antibody modestly delayed schwannoma growth [23]. In the clinical setting, a case report documented that αPD1 salvage therapy led to tumor growth arrest in a patient with recurrent VS [24]. This observation demonstrates the therapeutic potential of ICIs for VS and warrants further investigation into their efficacy on tumor growth and hearing preservation.

In this study, we aim to address three questions: 1) Can the combination of αPD1 and RT treatment enhance anti-tumor efficacy compared to each monotherapy? 2) Can the addition of αPD1 treatment reduce the required RT dose for tumor control, thereby minimizing potential RT-related ototoxicity and other adverse effects? and 3) can local irradiation of a peripheral nerve schwannoma elicit an abscopal effect that synergizes with systemic αPD1 treatment and shrinks intracranial vestibular schwannoma without direct irradiation, thus sparing the cochlea from RT-related ototoxicity and better preserving hearing function?

Materials and Methods

Cell lines. Mouse Nf2-/- Schwannoma cells were maintained in 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS)-containing Schwann cell medium with Schwann cell growth supplement (SCGS, ScienCell) [25]. Mouse SC4 Schwannoma cells (gift from Dr. Vijaya Ramesh, Massachusetts General Hospital, MGH) were maintained in 10% FBS-containing Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Corning) [26, 27]. Both tumor cell lines were infected with lentivirus encoding secreted Gaussia luciferase (Gluc) reporter gene to monitor tumor growth in the brain.

Animal models. All animal procedures were performed following the Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the MGH. Nf2-/- and SC4 tumors were implanted in immune-competent C57/FVB mice. In all animal experiments, we used 8-12 weeks-old mice in an equal ratio of male and female mice (1:1) and used age- and sex-matched mice.

Cerebellopontine angle (CPA) model: To recapitulate the intracranial microenvironment of VSs, tumor cells were implanted into the CPA region of the right hemisphere [28, 29]. A total of 1 μl of tumor cell suspension (2,500 cells) was implanted per mouse. To evaluate tumor growth in the brain, blood levels of secreted Gluc were measured as described before [29-32].

Sciatic nerve schwannoma model: To reproduce the microenvironment of peripheral schwannomas, we implanted tumor cells into the mouse sciatic nerve [26]. A total of 3 μl of tumor cell suspension (5x104 cells) was injected slowly (over 45-60 seconds) under the sciatic nerve sheath using a Hamilton syringe to prevent leakage. The sciatic nerve tumor size was measured using a caliper every 3 days until tumors reached 1 cm in diameter.

Treatment protocols. In the sciatic nerve model, treatment starts when the tumor reaches 3 mm in diameter. In the CPA model, treatment starts when the blood Gluc reaches 1x104 RLU.

Anti-PD1 treatment. The anti-PD1 antibody or isotype control IgG (200 μg/mouse, Bioxell) was administered i.p. every 3 days for a total of 4 dosages.

Radiation therapy. Treatment was delivered in a 137Cs gamma irradiator for small animals, which produces 1.176 MeV gamma rays and allows longitudinal radiation studies. Mice were irradiated locally in a custom-designed irradiation chamber, which shields the entire animal except for the brain (in the CPA model) or the leg (in the sciatic nerve model) [26]. We used 5 Gy or 10 Gy irradiation in our study based on a previously established protocol for mouse schwannoma models [26].

Audiometric testing in animals. Auditory brainstem responses (ABRs) were measured as described previously [29]. Briefly, animals were anesthetized via i.p. injection of ketamine (0.1 mg/g) and xylazine (0.02 mg/g). The tympanic membrane and the middle ear were microscopically examined for signs of otitis media. All animals had well-aerated middle ears. ABRs were recorded between subdermal needle electrodes: positive in the inferior aspect of the ipsilateral pinna, negative at the vertex, and ground at the proximal tail. The responses were amplified (10,000X), filtered (0.3-3.0 kHz), and averaged (512 repetitions) for each of the same frequencies and sound levels. Custom LabVIEW software for data acquisition was run on a PXI chassis (National Instruments Corp). For each frequency, the auditory threshold was defined as the lowest stimulus at which repeatable peaks could be observed on visual inspection. In the absence of an auditory threshold, a value of 85 dB was assigned (5 dB above the maximal tested level).

Analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. To characterize the tumor-infiltrating immune cells, tumor lysates were washed with PBS and stained for flow cytometry with anti-CD45 (clone 30-F11), anti-CD4 (clone RM4-5), anti-CD8 (clone 53-6.7), anti-Foxp3 (clone D6O8R), anti-NK1.1 (clone PK136), anti-Gr1 (clone RB6-8C5), anti-CD11b (clone m1/70), anti-F4/80 (clone BM8), anti-iNOS (clone CXNFT), anti-Arginase I (clone D4E3M), anti-CD86 (clone GL-1), anti-interferon (IFN-γ, clone XMG1.2), anti-TNFα (clone MP6-XT22), and anti-Granzyme B (clone GB11), see Supplementary Table 1 for antibody details.

Gene expression analysis. RNASeq. Fresh mouse tumor samples were homogenized using the polytron PT1300 tissue homogenizer, followed by additional homogenization using a Qiashredder spin column. RNA from tumor tissues was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Cambridge, MA). 1 μg of total RNA was sent to the Molecular Biology Core Facilities, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. RNASeq analysis was performed following the routine procedure [27]. The DESeq2 package in R was used to determine the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) [33]. To control for the False discovery rate (FDR) at 0.05, we used the Benjamini & Hochberg correction. The ComplexHeatmap package was used to plot the heatmap [34]. The differentially expressed gene set was analyzed by Gene Set Enrichment Analysis software (GSEA, https://software.broadinstitute.org/software/cprg/?q=node/14).

Quantitative RT-PCR. qPCR was performed by SYBR Green methods as previously described [35, 36].

Western Blot. Western blot membranes were blotted with antibodies against total (1:500) and phospho-STING (1:1000); total (1:500) and phospho-TBK1 (Ser172, 1:1,000); total (1:500) and phospho-IRF3 (Ser396, 1:1,000); HMGB1 (1:500), cGAS (1:500) and beta-actin (1:5,000). The corresponding secondary antibodies were used. Antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA) [37, 38].

ELISA. Plasma or tumor lysates (2 μg/μl concentration, triplicate for each sample) were analyzed using mouse multiplex enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay plates following the manufacturer's instructions (Meso-Scale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD) [35, 39].

In vitro viability and apoptosis assay. Cell viability was determined in vitro by MTT assay [40]. In vitro apoptosis was determined by Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (PI) staining followed by flow cytometry, following the manufacturer's instructions (Biolegend).

ATP release assay. ATP release was evaluated using the Luminescent ATP Detection Kit (Abcam) following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 50 µL of detergent was added to lyse the cells and stabilize the ATP. The plate was sealed and shaken for 5 minutes at 600-700 rpm. Then, 50 µL of substrate solution was added to each well, and luminescence was measured using a microplate reader. ATP levels were calculated by comparing luminescence values to a standard curve prepared using known ATP concentrations.

Histological staining. Tumor cell proliferation (PCNA+, 1:1,000, Abcam) and apoptosis (TUNEL+, ApopTag®, EMD Millipore) were evaluated by immunohistochemical staining [39]. Archived paraffin-embedded patient VS samples were stained with antibodies against phosphorylated TBK (1:10, Cell Signaling Technology). Normal peripheral nerves (n=4) obtained postmortem were used as controls. Histological analysis with digital image quantification was conducted using ImageJ. Positive staining in 20 random fields/slides was quantified via automated functions based on fluorescent intensity, with a threshold to exclude background staining.

Statistical analyses. Differences in sciatic nerve tumor growth were analyzed using repeated measures two-way ANOVA. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were analyzed by the Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. ABR thresholds were analyzed with a linear mixed-effects model. Flow cytometry, ELISA, qPCR, and cytotoxicity studies were analyzed using Student's t-test and Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate. All statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism Software version 9.

Results and Discussion

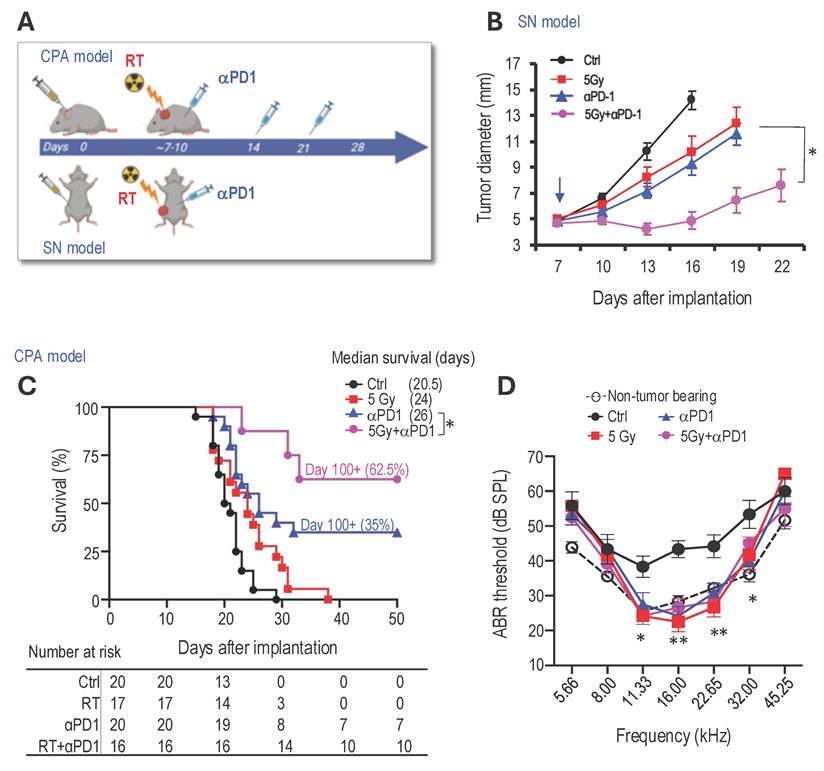

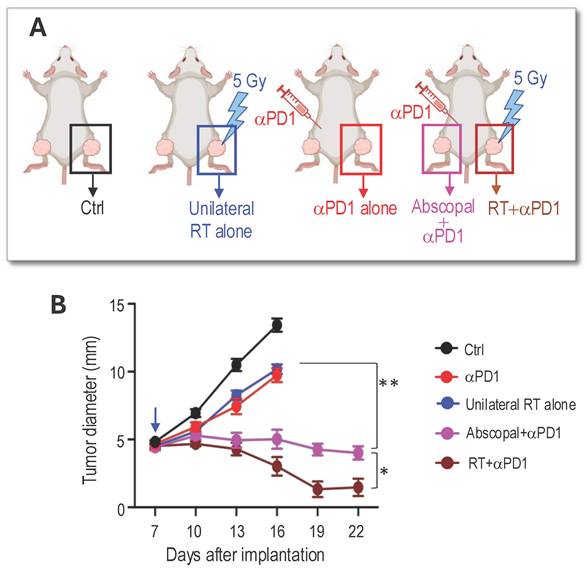

Combined radiotherapy and αPD1 show improved tumor control efficacy in both schwannoma models. To address our first question of whether combined RT+αPD1 treatment can achieve enhanced efficacy, we treated mice bearing Nf2-/- tumors in both sciatic nerve and CPA models with: i) control IgG, ii) αPD1, iii) 5Gy RT, or iv) αPD1+5Gy RT (Figure 1A). In the sciatic nerve model, both RT and αPD1 monotherapy modestly delayed tumor growth, and combined RT+αPD1 treatment was significantly more effective in tumor growth inhibition compared to each monotherapy (Figure 1B). In the CPA model, combined RT+αPD1 treatment significantly prolonged survival - with 62.5% of mice surviving ≥100 days, compared to 32% of long-term survivor mice in the αPD1 monotherapy group (Figure 1C). This improved efficacy of the combination treatment was similarly observed in a second schwannoma model, SC4 (Supplemental Figure 1A).

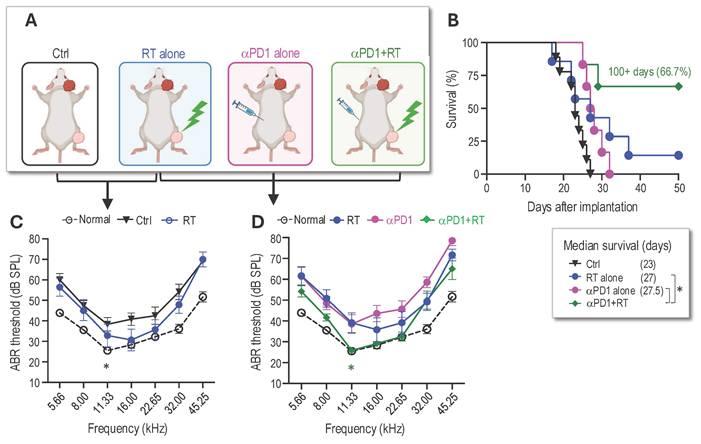

The impact of immunotherapy on hearing has not been systematically assessed. To assess potential ototoxicity, we examined the effects of 5 Gy RT and combined 5Gy + αPD1 treatment in non-tumor-bearing mice by measuring auditory brainstem evoked response (ABR). We observed that neither 5 Gy RT nor the combined 5Gy + αPD1 treatment altered the ABR threshold in mice at both 1 day and 42 days post-treatment (Supplemental Figure 1B-D). In mice with Nf2-/- tumors in the CPA region, treatment with αPD1, 5 Gy RT, or their combination restored ABR threshold to levels comparable to those in non-tumor-bearing mice. However, no treatment is more effective than the others (Figure 1D).

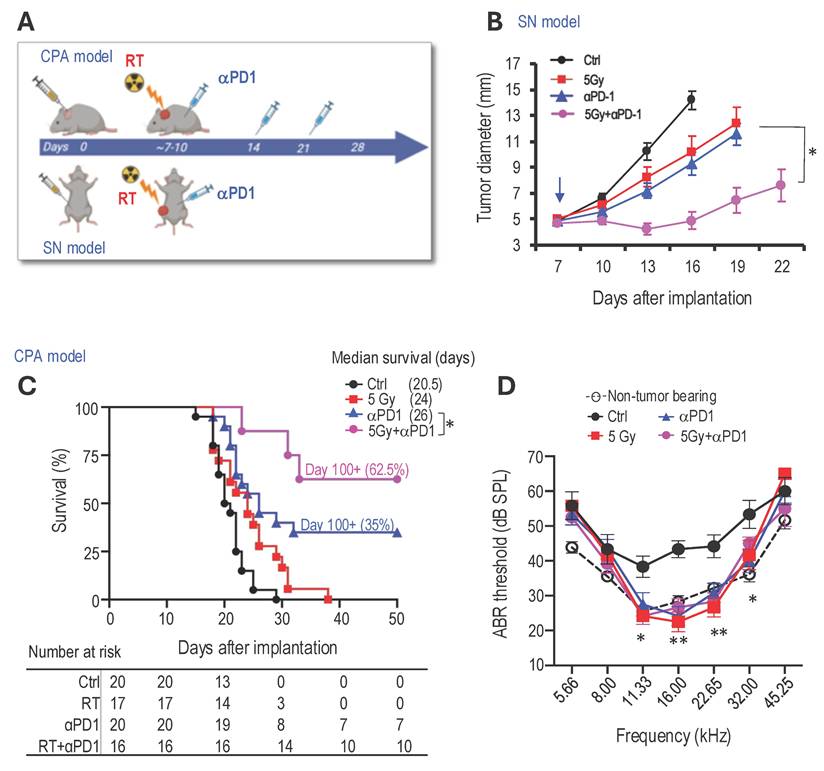

Combined radiotherapy and αPD1 treatment generates immunologic memory. To test whether long-term survivors develop durable immune memory, we first examined the memory T cell populations using flow cytometry (Figure 2A). Compared to treatment-naïve mice, long-term survivors showed significantly increased CD4+ and CD8+ central memory T cells (TCM: CD44+CD62L+), moderately increased CD4+ effector memory T cells (TEM: CD44+CD62L-), and significantly increased CD8+ TEM (Figure 2B).

Next, we re-challenged 'cured' mice (the initial tumor completely disappeared as confirmed by negative Gluc measurement, and mice survived over 100 days) with injections of Nf2-/--Gluc cells into the CPA region contralateral to the previous injection (Figure 2C). Naïve mice were included as controls for tumor take. In naïve mice, 100% developed tumors, and their blood Gluc reporter gene levels exceeded 1x106 RLU by day 14 after implantation. On the contrary, by day 63 after the rechallenge implantation, none of the 'cured' mice developed tumors (Figure 2D). These data suggest that the 'cured' mice have long-term tumor-specific immunological memory against the Nf2-/- cells.

Lastly, to evaluate whether T cells are critical for the anti-tumor immune memory in long-term survivors, a separate cohort of mice that had cleared tumors after combined therapy was rechallenged by implanting new tumors in the contralateral CPA region. Following rechallenge, mice were randomized to receive either control IgG or depleting antibodies against CD4 and CD8 T cells (Figure 2E). Long-term survivors treated with control IgG showed robust immune protection and failed to develop detectable tumors for more than 6 weeks after rechallenge. In contrast, T cell depletion abolished this protection, and mice rapidly developed progressive tumors (Figure 2F), demonstrating that T cells are required for maintaining long-term antitumor immunity in this model.

Combined αPD1 treatment reduced the radiotherapy dose required for tumor control. Key determinants of hearing loss after RT are the radiation dose and the volume of the cochlea irradiated, with lower radiation doses associated with better hearing preservation [41]. To address our second question, whether combined αPD1 treatment helps lower the required RT dose for tumor control, thereby minimizing potential RT-related ototoxicity and adverse events, we treated groups of mice with i) control IgG, ii) 5 Gy RT, iii) 10 Gy RT, or iv) 5 Gy RT+PD1. In both sciatic nerve (Figure 2G) and CPA (Figure 2H) models, we found that high-dose RT (10 Gy) was more effective than low-dose RT (5 Gy) in delaying tumor growth and prolonging survival. However, when combined with αPD1 treatment, 5 Gy RT was more effective than 10 Gy RT alone. These data suggest that combining αPD1 treatment with RT could help lower the required RT dose for tumor control.

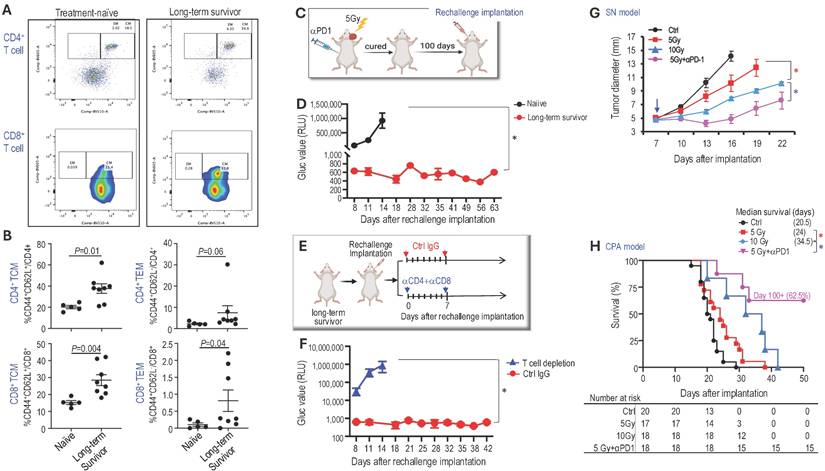

RT induces immunogenic cell death in schwannoma models. Using RNASeq analysis to screen for changes in gene expression, we found that irradiation of an Nf2-/- tumor led to a significant upregulation of genes involved in pyroptosis (Figure 3A). Irradiated tumors showed increased gene expression of i) pyroptosis executors, including Gasdermin D (Gsdmd) and Gasdermin E (Gsdme), ii) caspases that cleave Gasdermin D, such as Caspase 1 (Casp1) and Caspase 4 (Casp4), and iii) inflammasomes, upstream activators of pyroptosis, including Nlrp1 and Nlrc4 (Figure 3B). Because pyroptosis is a form of immunogenic cell death (ICD) that can trigger robust systemic immune activation [42][43], these findings prompted us to investigate whether radiation therapy induces pyroptosis in our schwannoma models.

Combined radiotherapy and αPD1 show improved tumor efficacy in both schwannoma models. (A) Schematic and timeline of combined radiation therapy and αPD1 treatment in the CPA and SN schwannoma models. (B) Tumor diameter measured by caliper in the SN schwannoma model. Arrow, treatment start time. N=8/group, Data are presented as mean±s.e.m., and representative of at least three independent experiments, N=24 mice/group. (C) Kaplan-Meir survival curve of mice bearing Nf2-/- tumor in the CPA model. Ctrl (n=20), 5 Gy (n=17), αPD1 (n=20), Comb (n=16). (D) ABR threshold of mice bearing Nf2-/- tumor in the CPA model 21 days post-treatment. N=6/group, Data are presented as mean±s.e.m., and representative of at least three independent experiments, N=18 mice/group. Differences in sciatic nerve tumor growth was analyzed using repeated-measures two-way ANOVA. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were analyzed by Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. ABR thresholds were analyzed with a linear mixed-effects model. *P<0.01, **P<0.001.

Combined radiotherapy and αPD1 treatment generate immunologic memory and lowered the radiotherapy dose required for tumor control. (A) Flow cytometry gating strategies to analyze CD4+ and CD8+ central memory T cells (TCM: CD44+CD62L+) and effector memory T cells (TEM: CD44+CD62L-) immune memories cells in treatment naïve and long-term survivors. (B) Flow cytometry quantification of CD4+ and CD8+ central memory and effector memory T cells in treatment naïve (n=5) and long-term survivors (n=8). (C) Schematic and timeline of rechallenging experiment in long-term survivors. (D) Blood Gluc level in naïve (n=8) and long-term survivors (n=8). Data are presented as mean±s.e.m., and representative of at least three independent experiments, N=24 mice/group. (E) Schematic and timeline of rechallenging experiment in long-term survivors with and without T cell depletion using anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies. (F) Blood Gluc level in long-term survivors treated with control IgG (n=12) or anti-CD4 and CD8 (n=12). Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. (G) Tumor diameter measured by caliper in the SN schwannoma model. Data are presented as mean±s.e.m., and representative of at least three independent experiments, N=24 mice/group. (H) Kaplan-Meir survival curve of mice bearing Nf2-/- tumor in the CPA model. Ctrl (n=20), 5 Gy (n=17), 10 Gy (n=18), 5Gy+αPD1 (n=18). Differences in sciatic nerve tumor growth was analyzed using repeated-measures two-way ANOVA. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were analyzied by Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. *P<0.01.

RT induces immunogenic cell death in schwannoma models. RNAseq analysis of bulk tumors from control and irradiated Nf2-/- tumors from the CPA mouse model (N=3 tumors/group). (A) GSEA enrichment plots of GO_Pyroptosis pathway related genes. (B) Heatmap of pyroptosis pathway genes. Flow cytometry of Annexin V/Propidium iodide-stained control and 5 Gy in vitro irradiated Nf2-/- cells. (C) Flow cytometry gating of Annexin V/Propidium iodide. (D) Flow cytometry analysis of apoptotic or pyroptotic and necrotic Nf2-/- cells. Confirmation of RT-induced Pyroptosis-related gene expression changes. (E) Nf2-/- tumor cells were treated with or without 5Gy irradiation. Six hours later, cells were lyse and protein was extracted for Western blot analysis of GasderminD. (F) Fluorescent intensity of extracellular ATP release from control and in vitro 5 Gy irradiated Nf2-/- cells (n=6 plates/group). (G) Western blot analysis of GasderminD in control and 5 Gy irradiated Nf2-/- tumor tissues. (H) qRT-PCR analysis of murine Il-1β, Il-18, Ifn-β, Tnf-α, Il-6 and Ifn-γ mRNAs in control and 5 Gy irradiated Nf2-/- tumors (N=3 tumors/group). Flow cytometry and gene expression data are presented as mean±s.d., and analyzed using Student's t-test and the Mann-Whitney test. *P<0.01.

To determine whether radiation therapy induces pyroptosis, we first irradiated Nf2-/- cells in vitro and assessed cell death by flow cytometry (Figure 3C). Irradiation significantly increased tumor cell pyroptosis and necrosis (Figure 3D). To distinguish pyroptosis from necrosis, we evaluated Gasdermin D, the key executioner of pyroptosis [44, 45]. In irradiated Nf2-/- cells, western blot analysis demonstrated a shift from full-length to cleaved Gasdermin D, marked by reduced full-length protein and the appearance of the cleaved fragment (Figure 3E). Because adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is both a trigger for and a product of pyroptosis [46], we next measured extracellular ATP levels and found that irradiated Nf2-/- cells released significantly more ATP compared to control cells (Figure 3F).

We further confirmed in vivo that RT increased the level of cleaved Gasdermin D by western blot (Figure 3G) and upregulated several inflammatory cytokines by quantitative RT-PCR, including IL-1β and IL-18, which are canonical cytokines released during pyroptosis, as well as IFN-α, TNF-α, IL-6, and IFN-γ, which reflects the inflammatory response associated with pyroptotic cell death (Figure 3H). Together, these data demonstrate that RT activates a pyroptosis-associated inflammatory cell death program in the schwannoma models.

RT of peripheral nerve schwannoma elicits an abscopal effect and enhances αPD1 efficacy. We next performed an experiment to address our third question: whether local irradiation of a peripheral nerve schwannoma induces an abscopal effect that synergizes with systemic αPD1 treatment, leading to the shrinkage of intracranial vestibular schwannoma without direct irradiation. This approach aims to spare the cochlea from RT-related ototoxicity and better preserve hearing function. We bilaterally implanted Nf2-/- cells into the sciatic nerves of mice. When tumors grew to ~5 mm in diameter, mice were randomized into groups receiving control IgG or treatment with i) αPD1 only, ii) 5 Gy RT applied to the tumor on the right leg (unilateral RT alone), or iii) αPD1+5 Gy RT applied only to the tumor on the right leg, while the rest of the body was shielded (Figure 4A). Results indicated that while the group with the tumor receiving both direct RT and αPD1 had the best response (RT+ αPD1, brown line), the contralateral non-irradiated tumor receiving systemic αPD1 treatment plus the RT abscopal effect (Abscopal+αPD1, pink line) showed significantly reduced growth compared to tumors receiving either αPD1 (red line) or unilateral RT alone (blue line, Figure 4B).

RT of peripheral nerve schwannomas works additively with αPD1 to control intracranial tumors and preserve hearing. Based on the observed abscopal effects, we next investigated whether local irradiation of the sciatic nerve tumor could synergize with systemic αPD1 treatment to inhibit intracranial tumor growth and prevent hearing loss. In this study, we implanted tumors in both the sciatic nerve and the CPA area. When the sciatic nerve tumors reached ~5 mm in diameter, the mice were randomized into control or treatment groups of i) 5 Gy RT to the sciatic nerve tumor alone, ii) αPD1 alone, or iii) a combination of αPD1+5 Gy RT to the sciatic nerve tumor (Figure 5A). Mice were sacrificed when they exhibited ataxia, a symptom caused by the CPA tumors. Compared to the control group, local irradiation of the sciatic nerve tumor extended animal survival by 4 days (Figure 5B) and prevented tumor-induced hearing loss (Figure 5C). The RT abscopal effect, when combined with systemic αPD1 treatment, significantly prolonged mice survival, with 66.7% of animals surviving over 100 days (Figure 5B). More importantly, we found that irradiation of the sciatic nerve tumor synergized with systemic αPD1 treatment, more effectively preventing tumor-induced hearing loss than αPD1 monotherapy (Figure 5D).

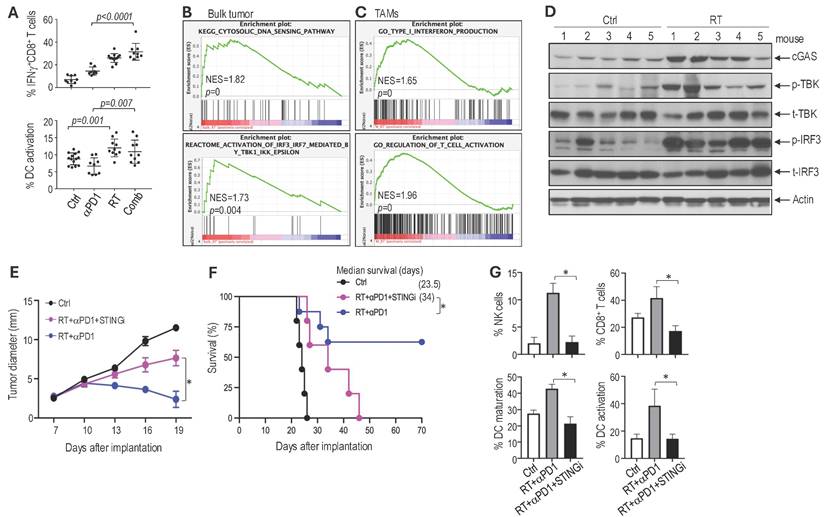

Combined radiotherapy and αPD1 treatment activates dendritic cells and CD8 T cells. Compared to the αPD1 monotherapy, the combination with RT resulted in a significant increase in intratumoral CD8+ T cells expressing interferon (IFN)-γ, a key cytokine produced by activated CD8+ T cells that is essential for antitumor immunity. Dendritic cells (DCs) are critical for priming CD8+ T cell responses; therefore, we evaluated DC activation state following treatment. Quantification of activated DCs showed that αPD1 monotherapy did not increase DC activation compared to control. In contrast, RT alone increased the intratumoral DCs expressing CD86, a costimulatory molecule essential for activating T cells. The combination of RT with αPD1 resulted in similarly elevated levels of DC activation. These data indicate that RT enhances antitumoral antigen presentation and promotes further activation of CD8 T cells (Figure 6A). The RT-induced increase in tumor-infiltrating T cells was further confirmed by immunofluorescent analysis (Supplemental Figure 2A). Consistent with increased immune activation, CPA tumors from mice in the combination treatment group exhibited a higher number of apoptotic tumor cells (TUNEL+) and a reduced number of proliferating tumor cells (PCNA+) compared to those in the control or monotherapy groups (Supplemental Figure 2B-C).

STING signaling mediates the therapeutic benefit observed with combined RT and αPD1 treatment in Schwannoma models. We next investigated the molecular mechanisms underlying the therapeutic benefit of the combination treatment. Using RNASeq, we profiled gene expression changes in both Nf2-/- bulk tumors and in tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). In the Nf2-/- bulk tumor, RT enriched gene signature associated with cytosolic DNA sensing and IRF3-TBK1 pathways (Figure 6B). In TAMs isolated from Nf2-/- tumors, RT induced enrichment of type I IFN and T cell activation pathways (Figure 6C). RT-induced DNA damage activates the cytosolic DNA-sensing pathway mediated by cGAS and stimulator of interferon genes (STING). STING recruits TBK1 and activates IRF3 to induce the expression of type I interferon (IFN), which activates the immune response [47, 48], and is critical for immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy and radiotherapy [49-52].

Using western blot analysis, we confirmed in the CPA tumors that RT induced the expression of cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP) synthase (cGAS), phosphorylation of TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1), and interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3)(Figure 6D). As the single-cell RNASeq data and bulk tumor signal transduction analysis converge on DNA sensing, IRF3-TBK, and IFN production, we focused on the STING pathway.

To investigate whether STING signaling contributes to the therapeutic benefit of the combination treatment, we treated mice bearing Nf2-/- tumors in the sciatic nerve with i) control, ii) RT+αPD1, and iii) RT+αPD1+selective STING inhibitor (H151). We found that the addition of the STING inhibitor abolished the therapeutic benefits of the combination treatment: i) H151 significantly reduced the tumor growth delay achieved by the combination therapy (Figure 6E), ii) shortened median survival to 34 days, compared to the 62.5% long-term survival rate observed in the combination treatment group (Figure 6F), and iii) abolished the combination treatment-induced recruitment of immune effector NK cells and CD8+ T cells as well as the activation of dendritic cells (Figure 6G). These data confirm that STING signaling contributes to the therapeutic benefit of the RT and αPD1 combination treatment.

RT of peripheral nerve schwannoma elicits an abscopal effect and additively with aPD1 efficacy. (A) Schematic of bilateral Nf2-/- tumor implantation, systemic αPD1 treatment, and local radiation therapy to the right sciatic nerve schwannoma. (B) Tumor diameter measured by caliper. All animal studies are presented as mean±s.e.m., N=24 mice/group. Differences in sciatic nerve tumor growth was analyzed using repeated-measures two-way ANOVA. *P<0.01. ** P<0.001.

RT of peripheral nerve schwannomas works additively with systemic αPD1 treatment to control intracranial tumors and preserve hearing. (A) Schematic of local irradiation of the sciatic nerve Nf2-/- tumor and systemic αPD1 treatment in mice bearing Nf2-/- CPA tumors. (B) Kaplan-Meir survival curve of mice. (C) ABR threshold of the ear ipsilateral to tumor implantation in non-tumor bearing (black dotted line), control (black line), and 5 Gy RT alone (blue line) groups. (D) ABR threshold of the ear ipsilateral to tumor implantation in non-tumor bearing mice (black dotted line), and in mice receiving 5Gy RT alone to the SN tumor (blue line), i.p. injection of αPD1 alone (pink line), or 5 Gy to the SN tumor + i.p. injection of αPD1 (green line). *P<0.01 for green vs. blue and green vs. pink. All animal studies are presented as mean±s.e.m., N=18 mice/group, and representative of at least three independent experiments. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were analyzed by Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. ABR thresholds were analyzed with a linear mixed-effects model. *P<0.01.

Discussion

RT is the standard of care for progressive or symptomatic vestibular schwannomas [53]. Although fractionated radiation therapy has excellent tumor control, patients typically experience hearing deterioration within six months of radiation therapy, suggesting that hearing loss results from RT-induced ototoxicity rather than tumor progression [41]. The goal of our study is to develop a therapeutic strategy that spares the cochlea from direct irradiation to minimize auditory radiation injury and better preserve hearing function in patients with NF2-SWN.

Multiple preclinical studies have shown that radiotherapy stimulates antitumor immunity through several complementary mechanisms: i) increasing tumor immunogenicity by increasing neoantigen expression and antigen presentation [54], ii) reprogramming the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment by inducing immunostimulatory cytokines such as type I interferon [55], and iii) promoting the recruitment of antigen-presenting cells and immune effector cells to the tumor microenvironment [56]. Consistent with these effects, numerous preclinical studies have demonstrated that combining radiotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors yields synergistic antitumor responses [57, 58]. These findings provide a strong rationale for RT-ICI combinations, which may not only enhance therapeutic efficacy but also enable reduced radiation doses to achieve tumor control and potentially lower the risk of RT-related ototoxicity.

In our studies, we demonstrated that the combination of αPD1 treatment with RT provides three significant benefits: i) enhanced αPD1 efficacy and immune memory, ii) reduced RT dose and associated tissue injury, and iii) elicited abscopal effects on intracranial schwannomas, sparing the cochlea from radiation exposure and avoiding auditory radiation injury. The novelty of our work is twofold: i) first systematic evaluation of immunotherapy in a non-malignant tumor: To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive assessment of immunotherapy in a non-malignant tumor setting, with dual emphasis on both tumor control and preservation of neurological function (hearing); and ii) clinically relevant innovation for vestibular schwannoma: We identified a potential strategy to avoid direct cochlear irradiation, which may help reduce radiation-induced auditory injury - a clinical issue uniquely relevant to vestibular schwannoma management and not addressable in prior malignant tumor studies.

STING signaling mediates the therapeutic benefits observed in the combined RT and aPD1 treatment in Schwannoma models. (A) Flow cytometry analysis of IFNg expressing CD8+ T cells (% of IFNg+ CD8 T cell/CD8+CD3+CD45+) and activated dendritic cells (% of CD86+CD11c+CD11blow/-CD45+/CD11c+CD11blow/-CD45+) and in Nf2-/- tumors. (B) GSEA enrichment plots comparing irradiated vs. non-irradiated control bulk Nf2-/- tumors. (C) GSEA enrichment plots of TAMs isolated from irradiated vs. non-irradiated control Nf2-/- tumors. (D) Western blot analysis of STING pathway in tumor tissues (N=5 tumors/group). (E) Tumor diameter measured by caliper. (F) Kaplan-Meir survival curve of mice. (G) Flow cytometry analysis of NK cells, CD8 T cells, and dendritic cell maturation and activation in Nf2-/- tumors. All animal studies are presented as mean±s.e.m., N=24 mice/group, and representative of at least three independent experiments. Differences in sciatic nerve tumor growth was analyzed using repeated-measures two-way ANOVA. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were analyzed by Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Gene expression and flow cytometry data are presented as mean ± s.d., and analyzed using Student's t-test and the Mann-Whitney test. *P<0.01.

Our first finding is that RT, by inducing immunogenic cell death and activating the STING pathway, enhances the efficacy of αPD1 treatment. Although immunotherapy has transformed cancer treatment, its efficacy as monotherapy is still limited, with ICIs providing benefits to only 20-30% of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), renal cell carcinoma, or melanoma [59]. To date, indications for ICIs have often combined treatment strategies to enhance efficacy. In addition to its direct tumoricidal effects, focal RT can trigger systemic anti-tumor immunity by: i) promoting in situ vaccination through the release of tumor-associated neoantigens [60], ii) activating dendritic cells to enhance cancer cell recognition by cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) [52], and iii) inducing immunogenic cell death [61]. Combined RT and immunotherapy have shown increased efficacy in mouse models of colorectal cancer [62], breast cancer [57], pancreatic tumor [63]; however, this strategy has not been evaluated in non-malignant schwannoma models.

In our VS model, we observed that RT induced immunogenic cell death, a form of regulated cell death that is sufficient to activate an adaptive immune response [64]. Specifically, irradiation led to the release of immunostimulatory damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), including ATP and HMGB1, from irradiated, dying tumor cells. At the molecular level, we found that RT activated the cGAS/STING pathway, leading to increased production of type I interferon, TNFα, and IL-1β. These RT-induced immune mediators may support αPD1 therapy to enhance its efficacy. Future genetic studies, such as siRNA-mediated knockdown or CRISPR-based gene editing of ICD genes (HMGB1, Gasdermin D, IL-1β, and IL-18), and key STING pathway members (cGAS, TBK, and IRF3) - will be crucial in definitively establishing the functional roles of these pathways and determining which molecular pathway drives the therapeutic benefit. Despite encouraging preclinical data on the improved efficacy of RT and αPD1 combination therapy, clinical studies have yielded mixed results. Maintenance αPD1 treatment following standard-of-care chemoradiotherapy has been shown to enhance overall survival (OS) in patients with NSCLC [65, 66]; neoadjuvant stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) combined with durvalumab (an aPD-L1 antibody) increases durvalumab response in early-stage NSCLC [67], while nivolumab (an aPD1 antibody) improves disease-free survival in NSCLC patients who received neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy [68]. Conversely, clinical studies in glioblastoma and head & neck squamous cell carcinomas failed to demonstrate a therapeutic benefit over RT or immunotherapy alone [69-72]. Our findings provide a rationale for future clinical trials of this combination strategy in patients with VS, suggesting that optimally combining RT with immunotherapy may be a key to unlocking the potential of both therapies.

Secondly, we found that combined αPD-1 blockade can reduce the RT dose required for effective tumor control. Radiation therapy is known to cause permanent sensorineural hearing loss in a dose-dependent, progressive manner [73], and RT can also cause conductive hearing loss due to ear canal stenosis [74]. Developing combination treatment regimens that reduce the RT dose while maintaining clinical efficacy is essential to minimize ototoxicity in VS therapies. In our VS model, we found that adding an αPD1 treatment reduced the RT dose required to control tumor growth, suggesting that this combination strategy could help mitigate RT-induced ototoxicity. These findings support further clinical investigation of combined RT and αPD1 treatment in patients with VS to enhance therapeutic outcomes and preserve hearing function. One limitation of our preclinical studies is that mouse tumors grow more rapidly than patient schwannomas, which limits our ability to investigate long-term radiation-induced ototoxicity. Several generations of Nf2 tumor suppressor gene knockout mice have been developed, but earlier models failed to produce schwannomas characteristic of NF2-SWN [75]. More recently, an improved conditional knockout model using tissue-restricted Nf2 gene excision (Postn-Cre;Nf2flox/flox) was generated. These mice develop microscopic Schwann cell hyperplasia at 3-4 months, macroscopic Schwannomas along spinal, peripheral, and cranial nerves by 6-8 months, and exhibit hearing and balance deficits [76]. This slower and more physiological growth course would be ideal for studying long-term treatment effects. Future efforts to use these mice will be necessary for better recapitulating the slow-growing, non-malignant nature of schwannomas.

Lastly, as NF2-SWN patients often develop schwannomas throughout the body, we simultaneously implanted schwannoma cells in the CPA and in the sciatic nerve in mice. We observed that irradiation of a peripheral nerve tumor induced an abscopal effect that synergized with systemic αPD1 treatment, effectively controlling intracranial tumor growth and, more importantly, preventing tumor-induced hearing loss without the need for direct irradiation of the CPA tumor. This strategy holds substantial clinical potential. Hypo-fractionated RT can elicit an abscopal effect, limiting the progression of distant tumors outside the locally irradiated area [77], and synergizing with ICI in both preclinical breast cancer, colorectal cancer, melanoma, and lung cancer mouse models [57, 78-80], and lung cancer and melanoma patients [81, 82]. The cochlea is particularly sensitive to RT compared to either the brain or the auditory nerve [83, 84]. Direct irradiation of the cochlea can damage critical auditory structures, including the organ of Corti, basilar membrane, spiral ligament, and stria vascularis, as well as causing outer hair cell loss in the basal turn. This damage is most manifested in the high-frequency hearing loss observed in patients [85]. Our findings suggest that targeting peripheral nerve tumors while avoiding direct cochlear irradiation could reduce treatment-related side effects and better preserve hearing. This combination approach represents a promising shift toward more personalized, less toxic VS treatments. Additional human model studies will be essential for advancing our preclinical findings toward clinical translation. However, generating such data is challenging as VS is a rare disease, and surgical samples - particularly after radiotherapy - are extremely limited. Future studies with larger, multi-institutional patient cohorts will be critical for validating the immune-modulatory effects of radiotherapy. Furthermore, future studies incorporating patient-derived schwannoma cell lines using humanized mouse models will provide further support for advancing combined RT and αPD1 therapy toward clinical evaluation in VS.

Conclusions

In summary, our studies demonstrate that combining αPD1 treatment with RT significantly improves the efficacy of both therapies. Combined RT enhances the effectiveness of αPD1 therapy by promoting immunogenic cell death and activating the STING pathway, while combined αPD1 therapy allows for a reduced RT dose, potentially minimizing RT-induced ototoxicity and other adverse effects. Most importantly, RT induces an abscopal effect that effectively controls intracranial tumors without directly irradiating the cochlea. This approach has the potential to protect the cochlea from radiation exposure, thereby preventing auditory damage and preserving hearing function. Our findings highlight the therapeutic potential of combining RT and αPD1 to optimize tumor control while minimizing treatment-related side effects, paving the way for more targeted and patient-centered cancer therapies.

Abbreviations

ABR: Auditory brainstem response

αPD1: anti-PD1

Casp: Caspase 1

cGAS: Cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP) synthase

CPA: Cerebellopontine angle

CTL: Cytotoxic T lymphocytes

CTLA-4: Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4

DAMP: Damage-associated molecular patterns

DEG: Differentially expressed gene

DMEM: Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium

FBS: Fetal bovine serum

FDR: False discovery rate

Gsdmd: Gasdermin D

GSEA: Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

Gluc: Gaussia luciferase

ICI: Immune checkpoint inhibitor

IRF3: Interferon regulatory factor 3

NF2-SWN: NF2-related schwannomatosis

NSCLC: Non-small cell lung cancer

OS: Overall survival

PD-1: Programmed cell death protein-1

PI: Propidium iodide

RT: Radiotherapy

SBRT: Stereotactic body radiotherapy

SCGS: Schwann cell growth supplement

SNHL: Sensorineural hearing loss

TBK1: TANK-binding kinase 1

TCM: Central memory T cells

TEM: Effector memory T cells

VS: Vestibular schwannoma

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures and table.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mark Duquette and Anna Khachatryan for their superb technical support, and Dr. Peigen Huang for assisting in animal studies. We acknowledged that ChatGPT was only used for language editing.

Funding: This study was supported by the NIH R01-NS126187 and R01-DC020724 (to L.X.), Department of Defense New Investigator Award (W81XWH-16-1-0219, to L.X.), Investigator-Initiated Research Award (W81XWH-20-1-0222, to L.X.), Clinical Trial Award (W81XWH2210439, to S.R.P. and L.X.), Children's Tumor Foundation Drug Discovery Initiative (to L.X.), Children's Tumor Foundation Clinical Research Award (to L.X. and S.R.P.), and American Cancer Society Mission Boost Award (MBGII-24-1255260-01-MBG to L.X.).

Authorship contributions: L.X. designed the research and supervised the research; Z.Y., S. L., L.W., D.W.B., J.C. performed mouse model studies; S.L., D.C.B., L.D.L. conducted hearing test, Z.Y., Y.S., B.X., A.P.J., performed flow cytometry and histology analysis; W.H. analyzed RNASeq data; Z.Y., B.X., performed patient sample histological analysis; L.X., Z.Y., S.L., L.W., A.M., analyzed data; L.X., S.R.P., K.S., H.A.S., and wrote the paper.

Data availability: Data and the supplementary materials are available upon reasonable request, and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the corresponding author, LX (lexu@mgh.harvard.edu). This study did not generate new unique reagents. This paper does not report original code.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by MGH's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol #2016N00004).

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Evans DG. Neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2): a clinical and molecular review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2009;4:16

2. Forde C, Smith MJ, Burghel GJ, Bowers N, Roberts N, Lavin T. et al. NF2-related schwannomatosis and other schwannomatosis: an updated genetic and epidemiological study. J Med Genet. 2024;61:856-60

3. Evans DG, Moran A, King A, Saeed S, Gurusinghe N, Ramsden R. Incidence of vestibular schwannoma and neurofibromatosis 2 in the North West of England over a 10-year period: higher incidence than previously thought. Otology & neurotology: official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology. 2005;26:93-7

4. Plotkin SR, Merker VL, Muzikansky A, Barker FG 2nd, Slattery W 3rd. Natural history of vestibular schwannoma growth and hearing decline in newly diagnosed neurofibromatosis type 2 patients. Otology & neurotology: official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology. 2014;35:e50-6

5. Masuda A, Fisher LM, Oppenheimer ML, Iqbal Z, Slattery WH. Hearing changes after diagnosis in neurofibromatosis type 2. Otology & neurotology: official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology. 2004;25:150-4

6. Ammoun S, Hanemann CO. Emerging therapeutic targets in schwannomas and other merlin-deficient tumors. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:392-9

7. Plotkin SR, Merker VL, Halpin C, Jennings D, McKenna MJ, Harris GJ. et al. Bevacizumab for progressive vestibular schwannoma in neurofibromatosis type 2: a retrospective review of 31 patients. Otology & neurotology: official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology. 2012;33:1046-52

8. Watanabe S, Yamamoto M, Kawabe T, Koiso T, Yamamoto T, Matsumura A. et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for vestibular schwannomas: average 10-year follow-up results focusing on long-term hearing preservation. J Neurosurg. 2016;125:64-72

9. Frischer JM, Gruber E, Schoffmann V, Ertl A, Hoftberger R, Mallouhi A. et al. Long-term outcome after Gamma Knife radiosurgery for acoustic neuroma of all Koos grades: a single-center study. J Neurosurg. 2018:1-10

10. Huang CW, Tu HT, Chuang CY, Chang CS, Chou HH, Lee MT. et al. Gamma Knife radiosurgery for large vestibular schwannomas greater than 3 cm in diameter. J Neurosurg. 2018;128:1380-7

11. Breshears JD, Chang J, Molinaro AM, Sneed PK, McDermott MW, Tward A. et al. Temporal Dynamics of Pseudoprogression After Gamma Knife Radiosurgery for Vestibular Schwannomas-A Retrospective Volumetric Study. Neurosurgery. 2019;84:123-31

12. Hayhurst C, Zadeh G. Tumor pseudoprogression following radiosurgery for vestibular schwannoma. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14:87-92

13. Schmitt WR, Carlson ML, Giannini C, Driscoll CL, Link MJ. Radiation-induced sarcoma in a large vestibular schwannoma following stereotactic radiosurgery: case report. Neurosurgery. 2011;68:E840-6 discussion E6

14. Boucher AB, Mendoza P, Neill SG, Eaton B, Olson JJ. High-Grade Sarcoma Arising within a Previously Irradiated Vestibular Schwannoma: A Case Report and Literature Review. World Neurosurg. 2020;144:99-105

15. Demetriades AK, Saunders N, Rose P, Fisher C, Rowe J, Tranter R. et al. Malignant transformation of acoustic neuroma/vestibular schwannoma 10 years after gamma knife stereotactic radiosurgery. Skull Base. 2010;20:381-7

16. Ribas A, Wolchok JD. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science. 2018;359:1350-5

17. Chen DS, Mellman I. Elements of cancer immunity and the cancer-immune set point. Nature. 2017;541:321-30

18. Li B, Jin J, Guo D, Tao Z, Hu X. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Combined with Targeted Therapy: The Recent Advances and Future Potentials. Cancers (Basel). 2023 15

19. Wang S, Liechty B, Patel S, Weber JS, Hollmann TJ, Snuderl M. et al. Programmed death ligand 1 expression and tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in neurofibromatosis type 1 and 2 associated tumors. J Neurooncol. 2018;138:183-90

20. Li Z, Liu X, Guo R, Wang P. TIM-3 plays a more important role than PD-1 in the functional impairments of cytotoxic T cells of malignant Schwannomas. Tumour Biol. 2017;39:1010428317698352

21. Amit M, Xie T, Gleber-Netto FO, Hunt PJ, Mehta GU, Bell D. et al. Distinct immune signature predicts progression of vestibular schwannoma and unveils a possible viral etiology. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022;41:292

22. Archibald DJ, Neff BA, Voss SG, Splinter PL, Driscoll CL, Link MJ. et al. B7-H1 expression in vestibular schwannomas. Otology & neurotology: official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology. 2010;31:991-7

23. Ahmed SG, Oliva G, Shao M, Wang X, Mekalanos JJ, Brenner GJ. Intratumoral injection of schwannoma with attenuated Salmonella typhimurium induces antitumor immunity and controls tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119:e2202719119

24. Kouzel Martinez F, Graffeo CS, Carlstrom LP, Link MJ. Growth arrest of a refractory vestibular schwannoma after anti-PD-1 antibody treatment. BMJ Case Rep. 2021 14

25. Wong HK, Lahdenranta J, Kamoun WS, Chan AW, McClatchey AI, Plotkin SR. et al. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapies as a novel therapeutic approach to treating neurofibromatosis-related tumors. Cancer research. 2010;70:3483-93

26. Gao X, Zhao Y, Stemmer-Rachamimov AO, Liu H, Huang P, Chin S. et al. Anti-VEGF treatment improves neurological function and augments radiation response in NF2 schwannoma model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:14676-81

27. Wu L, Vasilijic S, Sun Y, Chen J, Landegger LD, Zhang Y. et al. Losartan prevents tumor-induced hearing loss and augments radiation efficacy in NF2 schwannoma rodent models. Sci Transl Med. 2021 13

28. Chen J, Landegger LD, Sun Y, Ren J, Maimon N, Wu L. et al. A cerebellopontine angle mouse model for the investigation of tumor biology, hearing, and neurological function in NF2-related vestibular schwannoma. Nat Protoc. 2019;14:541-55

29. Zhao Y, Liu P, Zhang N, Chen J, Landegger LD, Zhao F. et al. Targeting the cMET pathway augments radiation response without adverse effect on hearing in NF2 schwannoma models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E2077-E84

30. Chung E, Yamashita H, Au P, Tannous BA, Fukumura D, Jain RK. Secreted Gaussia luciferase as a biomarker for monitoring tumor progression and treatment response of systemic metastases. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8316

31. Tannous BA. Gaussia luciferase reporter assay for monitoring biological processes in culture and in vivo. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:582-91

32. Kodack DP, Chung E, Yamashita H, Incio J, Duyverman AM, Song Y. et al. Combined targeting of HER2 and VEGFR2 for effective treatment of HER2-amplified breast cancer brain metastases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E3119-27

33. Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550

34. Gu Z, Eils R, Schlesner M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:2847-9

35. Xu L, Duda DG, di Tomaso E, Ancukiewicz M, Chung DC, Lauwers GY. et al. Direct evidence that bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF antibody, up-regulates SDF1alpha, CXCR4, CXCL6, and neuropilin 1 in tumors from patients with rectal cancer. Cancer research. 2009;69:7905-10

36. Liao S, Liu J, Lin P, Shi T, Jain RK, Xu L. TGF-beta blockade controls ascites by preventing abnormalization of lymphatic vessels in orthotopic human ovarian carcinoma models. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1415-24

37. Zhao Y, Cao J, Melamed A, Worley M, Gockley A, Jones D. et al. Losartan treatment enhances chemotherapy efficacy and reduces ascites in ovarian cancer models by normalizing the tumor stroma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:2210-9

38. Xu L, Pathak PS, Fukumura D. Hypoxia-induced activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3'-kinase signaling pathways contributes to expression of interleukin 8 in human ovarian carcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:701-7

39. Xu L, Cochran DM, Tong RT, Winkler F, Kashiwagi S, Jain RK. et al. Placenta growth factor overexpression inhibits tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis by depleting vascular endothelial growth factor homodimers in orthotopic mouse models. Cancer research. 2006;66:3971-7

40. Xu L, Tong R, Cochran DM, Jain RK. Blocking platelet-derived growth factor-D/platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta signaling inhibits human renal cell carcinoma progression in an orthotopic mouse model. Cancer research. 2005;65:5711-9

41. Saraf A, Pike LRG, Franck KH, Horick NK, Yeap BY, Fullerton BC. et al. Fractionated Proton Radiation Therapy and Hearing Preservation for Vestibular Schwannoma: Preliminary Analysis of a Prospective Phase 2 Clinical Trial. Neurosurgery. 2022;90:506-14

42. Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Hett E, Kroemer G, Marincola FM. Immunogenic cell death in cancer: concept and therapeutic implications. J Transl Med. 2023;21:162

43. Kroemer G, Galassi C, Zitvogel L, Galluzzi L. Immunogenic cell stress and death. Nat Immunol. 2022;23:487-500

44. Kayagaki N, Stowe IB, Lee BL, O'Rourke K, Anderson K, Warming S. et al. Caspase-11 cleaves gasdermin D for non-canonical inflammasome signalling. Nature. 2015;526:666-71

45. Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang K, Shi X, Wang Y, Huang H. et al. Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature. 2015;526:660-5

46. Bergsbaken T, Fink SL, Cookson BT. Pyroptosis: host cell death and inflammation. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:99-109

47. Decout A, Katz JD, Venkatraman S, Ablasser A. The cGAS-STING pathway as a therapeutic target in inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21:548-69

48. Ishikawa H, Ma Z, Barber GN. STING regulates intracellular DNA-mediated, type I interferon-dependent innate immunity. Nature. 2009;461:788-92

49. Wang H, Hu S, Chen X, Shi H, Chen C, Sun L. et al. cGAS is essential for the antitumor effect of immune checkpoint blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:1637-42

50. Demaria O, De Gassart A, Coso S, Gestermann N, Di Domizio J, Flatz L. et al. STING activation of tumor endothelial cells initiates spontaneous and therapeutic antitumor immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:15408-13

51. Vanpouille-Box C, Alard A, Aryankalayil MJ, Sarfraz Y, Diamond JM, Schneider RJ. et al. DNA exonuclease Trex1 regulates radiotherapy-induced tumour immunogenicity. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15618

52. Deng L, Liang H, Xu M, Yang X, Burnette B, Arina A. et al. STING-Dependent Cytosolic DNA Sensing Promotes Radiation-Induced Type I Interferon-Dependent Antitumor Immunity in Immunogenic Tumors. Immunity. 2014;41:843-52

53. Thielhelm TP, Goncalves S, Welford SM, Mellon EA, Cohen ER, Nourbakhsh A. et al. Understanding the Radiobiology of Vestibular Schwannomas to Overcome Radiation Resistance. Cancers (Basel). 2021 13

54. Lussier DM, Alspach E, Ward JP, Miceli AP, Runci D, White JM. et al. Radiation-induced neoantigens broaden the immunotherapeutic window of cancers with low mutational loads. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 118

55. Di Maggio FM, Minafra L, Forte GI, Cammarata FP, Lio D, Messa C. et al. Portrait of inflammatory response to ionizing radiation treatment. J Inflamm (Lond). 2015;12:14

56. Rodriguez-Ruiz ME, Vitale I, Harrington KJ, Melero I, Galluzzi L. Immunological impact of cell death signaling driven by radiation on the tumor microenvironment. Nat Immunol. 2020;21:120-34

57. Demaria S, Kawashima N, Yang AM, Devitt ML, Babb JS, Allison JP. et al. Immune-mediated inhibition of metastases after treatment with local radiation and CTLA-4 blockade in a mouse model of breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:728-34

58. Dewan MZ, Galloway AE, Kawashima N, Dewyngaert JK, Babb JS, Formenti SC. et al. Fractionated but not single-dose radiotherapy induces an immune-mediated abscopal effect when combined with anti-CTLA-4 antibody. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5379-88

59. Dall'Olio FG, Marabelle A, Caramella C, Garcia C, Aldea M, Chaput N. et al. Tumour burden and efficacy of immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19:75-90

60. Frye MD, Ryan AF, Kurabi A. Inflammation associated with noise-induced hearing loss. J Acoust Soc Am. 2019;146:4020

61. Galluzzi L, Aryankalayil MJ, Coleman CN, Formenti SC. Emerging evidence for adapting radiotherapy to immunotherapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20:543-57

62. Rodriguez-Ruiz ME, Rodriguez I, Mayorga L, Labiano T, Barbes B, Etxeberria I. et al. TGFbeta Blockade Enhances Radiotherapy Abscopal Efficacy Effects in Combination with Anti-PD1 and Anti-CD137 Immunostimulatory Monoclonal Antibodies. Mol Cancer Ther. 2019;18:621-31

63. DeSelm C, Palomba ML, Yahalom J, Hamieh M, Eyquem J, Rajasekhar VK. et al. Low-Dose Radiation Conditioning Enables CAR T Cells to Mitigate Antigen Escape. Mol Ther. 2018;26:2542-52

64. Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Warren S, Adjemian S, Agostinis P, Martinez AB. et al. Consensus guidelines for the definition, detection and interpretation of immunogenic cell death. J Immunother Cancer. 2020 8

65. Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, Vicente D, Murakami S, Hui R. et al. Overall Survival with Durvalumab after Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2342-50

66. Zhou Q, Chen M, Jiang O, Pan Y, Hu D, Lin Q. et al. Sugemalimab versus placebo after concurrent or sequential chemoradiotherapy in patients with locally advanced, unresectable, stage III non-small-cell lung cancer in China (GEMSTONE-301): interim results of a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23:209-19

67. Altorki NK, McGraw TE, Borczuk AC, Saxena A, Port JL, Stiles BM. et al. Neoadjuvant durvalumab with or without stereotactic body radiotherapy in patients with early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer: a single-centre, randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:824-35

68. Kelly RJ, Ajani JA, Kuzdzal J, Zander T, Van Cutsem E, Piessen G. et al. Adjuvant Nivolumab in Resected Esophageal or Gastroesophageal Junction Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1191-203

69. Lim M, Weller M, Idbaih A, Steinbach J, Finocchiaro G, Raval RR. et al. Phase III trial of chemoradiotherapy with temozolomide plus nivolumab or placebo for newly diagnosed glioblastoma with methylated MGMT promoter. Neuro Oncol. 2022;24:1935-49

70. Omuro A, Brandes AA, Carpentier AF, Idbaih A, Reardon DA, Cloughesy T. et al. Radiotherapy combined with nivolumab or temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma with unmethylated MGMT promoter: An international randomized phase III trial. Neuro Oncol. 2023;25:123-34

71. Lee NY, Ferris RL, Psyrri A, Haddad RI, Tahara M, Bourhis J. et al. Avelumab plus standard-of-care chemoradiotherapy versus chemoradiotherapy alone in patients with locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:450-62

72. Bourhis J, Stein A, Paul de Boer J, Van Den Eynde M, Gold KA, Stintzing S. et al. Avelumab and cetuximab as a therapeutic combination: An overview of scientific rationale and current clinical trials in cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2021;97:102172

73. Bhandare N, Jackson A, Eisbruch A, Pan CC, Flickinger JC, Antonelli P. et al. Radiation therapy and hearing loss. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:S50-7

74. Nader ME, Gidley PW. Challenges of Hearing Rehabilitation after Radiation and Chemotherapy. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2019;80:214-24

75. Gutmann DH, Giovannini M. Mouse models of neurofibromatosis 1 and 2. Neoplasia. 2002;4:279-90

76. Gehlhausen JR, Park SJ, Hickox AE, Shew M, Staser K, Rhodes SD. et al. A murine model of neurofibromatosis type 2 that accurately phenocopies human schwannoma formation. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:1-8

77. Herrera FG, Bourhis J, Coukos G. Radiotherapy combination opportunities leveraging immunity for the next oncology practice. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:65-85

78. Deng L, Liang H, Burnette B, Beckett M, Darga T, Weichselbaum RR. et al. Irradiation and anti-PD-L1 treatment synergistically promote antitumor immunity in mice. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:687-95

79. Twyman-Saint Victor C, Rech AJ, Maity A, Rengan R, Pauken KE, Stelekati E. et al. Radiation and dual checkpoint blockade activate non-redundant immune mechanisms in cancer. Nature. 2015;520:373-7

80. Dovedi SJ, Adlard AL, Lipowska-Bhalla G, McKenna C, Jones S, Cheadle EJ. et al. Acquired resistance to fractionated radiotherapy can be overcome by concurrent PD-L1 blockade. Cancer research. 2014;74:5458-68

81. Formenti SC, Rudqvist NP, Golden E, Cooper B, Wennerberg E, Lhuillier C. et al. Radiotherapy induces responses of lung cancer to CTLA-4 blockade. Nat Med. 2018;24:1845-51

82. Postow MA, Callahan MK, Barker CA, Yamada Y, Yuan J, Kitano S. et al. Immunologic correlates of the abscopal effect in a patient with melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:925-31

83. Bohne BA, Marks JE, Glasgow GP. Delayed effects of ionizing radiation on the ear. Laryngoscope. 1985;95:818-28

84. Low WK, Tan MG, Chua AW, Sun L, Wang DY. 12th Yahya Cohen Memorial Lecture: The cellular and molecular basis of radiation-induced sensori-neural hearing loss. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2009;38:91-4

85. Asenov DR, Kaga K, Tsuzuku T. Changes in the audiograms of a nasopharyngeal cancer patient during the course of treatment: a temporal bone histopathological study. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127:1105-10

Author contact

![]() Corresponding author: Lei Xu (Department of Radiation Oncology, Edwin Steele Laboratories of Tumor Biology, Cox-7, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts 02114. Phone: 617-726-8051, Fax: 617-726-1962, lexuharvard.edu).

Corresponding author: Lei Xu (Department of Radiation Oncology, Edwin Steele Laboratories of Tumor Biology, Cox-7, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts 02114. Phone: 617-726-8051, Fax: 617-726-1962, lexuharvard.edu).

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact